For Marcy, my bride-to-be, and for my friends in Holy Cross, who teach and challenge me every day to be a man of God.

In an essay published a few weeks ago in Church Life, Timothy Radcliffe, OP, asked: can male religious be models of Christian masculinity? Radcliffe argued that through their vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience, male religious offer a model or a sign for young men entering adulthood:

Adult identity demands a narrative that gives unity to one’s life, a sense of its direction and goal. The crazy vows of religious say something of this, by pointing to the final end of every human life, which is the Kingdom. What possible sense could it have to reject marriage unless one believes that we are on our way to the vision of God? The vows are a naked sign of what it means to be a human being, which is to say yes to God who calls us to himself.

Two weeks before Radcliffe’s essay was published, I took my own step into adulthood by proposing to my girlfriend of three years—a step which has challenged me to think increasingly about what it means to be not only a man but a husband. But Radcliffe’s essay spoke to me on another level as well, as prior to meeting my fiancée I had spent nearly three years in an undergraduate seminary discerning the very religious life of which Radcliffe wrote. These were formative years of my life, during which I discovered myself and God’s will in my life, while forging some of my closest relationships as well: relationships that still nourish and sustain me to this day.

Thus, during these first weeks of my engagement I have found myself asking: what do the vows of religious life have to say to a young man preparing for marriage?

One way to approach this question is through the lens of desire. This takes us all the way back to our first parents, when Eve desired the fruit of the tree because she saw that “it was good for food, a delight to the eyes, and desired to make one wise” (Gen 3:6). This threefold desire corresponds to the exterior and interior human desires: desires of the flesh (those which relate to our physical embodiment), desires of the eyes (the desire to control things), and the pride of life (worldly ambition). This formed the topic of a lecture given by Fr. Kevin Grove, C.S.C., at the Center for Liturgy last summer, which he also draws out at length here.

The problem with human desires is not that they are bad—after all, Scripture describes the desires as being present in human beings even before the first sin—but as Grove pointed out in the video above, sin prevents us from properly integrating these desires. Thus one way of understanding the Christian life is as a life-long process of integration. In fact, we as a Church are engaging in this project right now in our Lenten practices of fasting (desires of the flesh), almsgiving (the desire to possess), and prayer (the desire to put our will above all else). In this framework, religious life and its vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience can be described as a school for the integration of human desire.

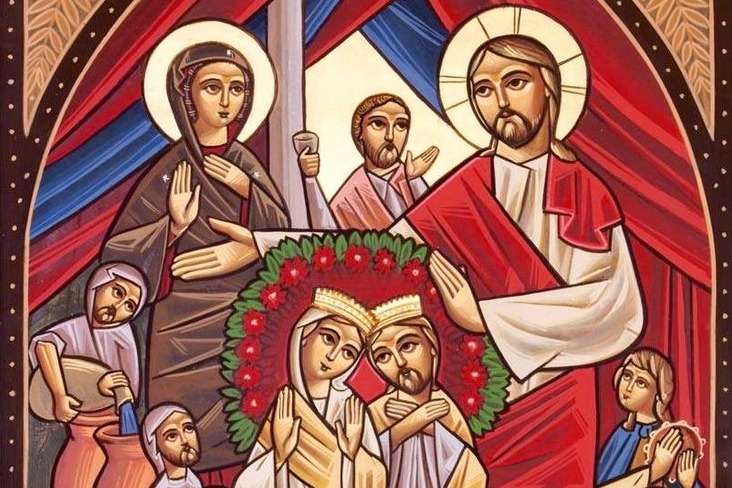

As my fiancée and I have discerned marriage these past few years, I have begun to realize that our marriage will be yet another school for this process of integration. Soon we will profess our vows to each other and to God, and at this time I will promise to be chaste: to love her and only her with my flesh and to not act on misguided desires of the flesh. I will promise to be poor: to share all that I have in common with her and our future children, and to claim nothing as my own. And I will promise to be obedient: to put the will of God before my own will, and to put her good before my own worldly ambition and desire for self-preservation.

As we prepare ourselves for this endeavor, we have the benefit of doing so alongside many friends who are preparing to profess their own perpetual religious vows in the Congregation of Holy Cross. These men have taught me that to be a man (and really, to be a human being), is to enter into this life-long process; to integrate our natural human desires into a singular, supernatural desire for God.

Yet ultimately I look to them not only for what they provide by their own witness, but to see Christ in them. Because if we want to know what the integration of human desire is meant to look like, we have only to look to Christ on the cross, the man who offered his flesh, his claim on worldly possessions, and his will in perfect sacrifice to the Father. We glimpse this image in the religious who professes and lives by his (or her) vows, and the man who does the same in marriage. This is not to say that the two states of life are interchangeable, but simply to claim that each derives its identity from a single source: the cross.

So what have I learned from the male religious in my life, those still in formation and those living their final profession of vows? I have learned that to be a man is to imitate Christ in his perfect integration and fulfillment of human desire: to commit to poverty, chastity, and obedience, pouring the entirety of one’s self out for the bride; to become a living sign of total self-gift.