Yes, of course the Catholic Worker is racist. As a human institution, the Catholic Worker is certainly sinful. Having said that, though, recent debates within the movement offer an opportunity not only for thinking about racism in the Catholic Worker, but also for considering this year’s theme of “Racism and the Church” more broadly. For instance, the 2017 College Theology Society Annual Volume included an article by Jessica Coblentz that was critical of how the annual meeting had been set that year. Coblentz faulted the conveners for not focusing enough on racism and racial injustice at a conference whose theme was US Catholicism in the twenty-first century. And as an example, she pointed to the fact that the call for papers had highlighted Dorothy Day, who Coblentz asserted was an advocate for economic justice, not racial justice.[1] I had never read Day criticized in this way—it was slightly jarring.

Prior to graduate school, I helped start the St. Peter Claver Catholic Worker in South Bend, an experience that has shaped my theology. In much of my research, I have tried to respond to criticism of Day and the Catholic Worker for being too sectarian or irresponsible or even irrelevant for their opposition to US economic and political institutions such as the US military. But the charge that Day should not be regarded as an advocate for racial justice was something new. Recently, though, this idea that Day, Peter Maurin, and the Catholic Worker that they co-founded in 1933 have not been dedicated to or “passionate” enough in the fight for racial justice has taken on an even more critical edge, with charges that the Catholic Worker is a racist institution.

All of this is relevant because it offers a telling snapshot of this moment in Catholic theology—where issues of race and identity have become prominent. To address this set of issues, I have divided my article into three parts. First, I will briefly summarize the recent charges of racism against the Day and the Catholic Worker. I will then try to historicize some of these claims, particularly through the lens of “racial capitalism”—an idea that has been gaining prominence recently. And finally, I will use this as an occasion for what Maurin called “clarification of thought” on racism and the Catholic Church more broadly.

I.

The fatal shooting of Michael Brown, a Black resident of Ferguson, Missouri by a white police officer on August 10, 2014, sparked months of protest and violence. In the wake of this, Catholic Workers from around the Midwest gathered for their annual Faith & Resistance retreat in 2015. Galvanized by the protests in nearby Ferguson and the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement, members of the St. Louis Catholic Worker asked that the retreat focus on anti-black racism, not only in the US in general but within the Catholic Worker movement in particular. Anti-black racism in the Catholic Worker would be the focus of the next two Faith & Resistance retreats.

At the end of the 2017 retreat, a group of these Midwest Catholic Workers issued an open letter on racism to the Catholic Worker movement titled “Lament. Repent. Repair.” The authors declared that after much study, activism, conversation, and prayer, they had come to the conclusion that “the Catholic Worker is a racist institution.” They stated that “communities of color have been ignored, undermined, and undervalued in the Catholic Worker movement, particularly since the beginning of World War II, when pacifism became a greater focus of the movement.” The authors published the letter first on the internet and then in the inaugural spring 2018 issue of The Catholic Worker Anti-Racism Review—an online publication edited by several of the authors of this letter.[2]

Not surprisingly, when it comes to a group of Catholic Workers, the response to “Lament. Repent. Repair.” was a bit volatile. Brian Terrell, a longtime Catholic Worker from Iowa wrote that while he was supportive of some of the letter’s suggestions, he thought that its refusal to distinguish between the Ku Klux Klan and the Catholic Worker betrayed “a shocking misunderstanding of how racism functions” and he pointed to the letter’s “strange silence on our country’s decades of racist wars.”[3] Terrell suggested that the issue was ultimately one of inexperience: “Until recent decades,” he pointed out, “there were always more Catholic Workers with criminal records than with university degrees . . . [but now] graduate school has taken the place of prison in the formation of many who have joined the Catholic worker in recent years.” A statement on racism by Catholic Workers “who have largely chosen to refuse the gift and avoid the redefinition of their lives that prison offers them,” Terrell declared “is by necessity limited in its prophetic potential.”

Ciaron O’Reilly, another longtime Catholic Worker and antiwar activist, was even less delicate. He called the authors arrogant “identity politics kids” who were out of their depth and that the letter read “like some kid [had] swallowed his Master's thesis and is now spitting it up in chunks” and wondered if maybe “Lament. Repent. Repair.” was their resignation letter from the Catholic Worker.[4]

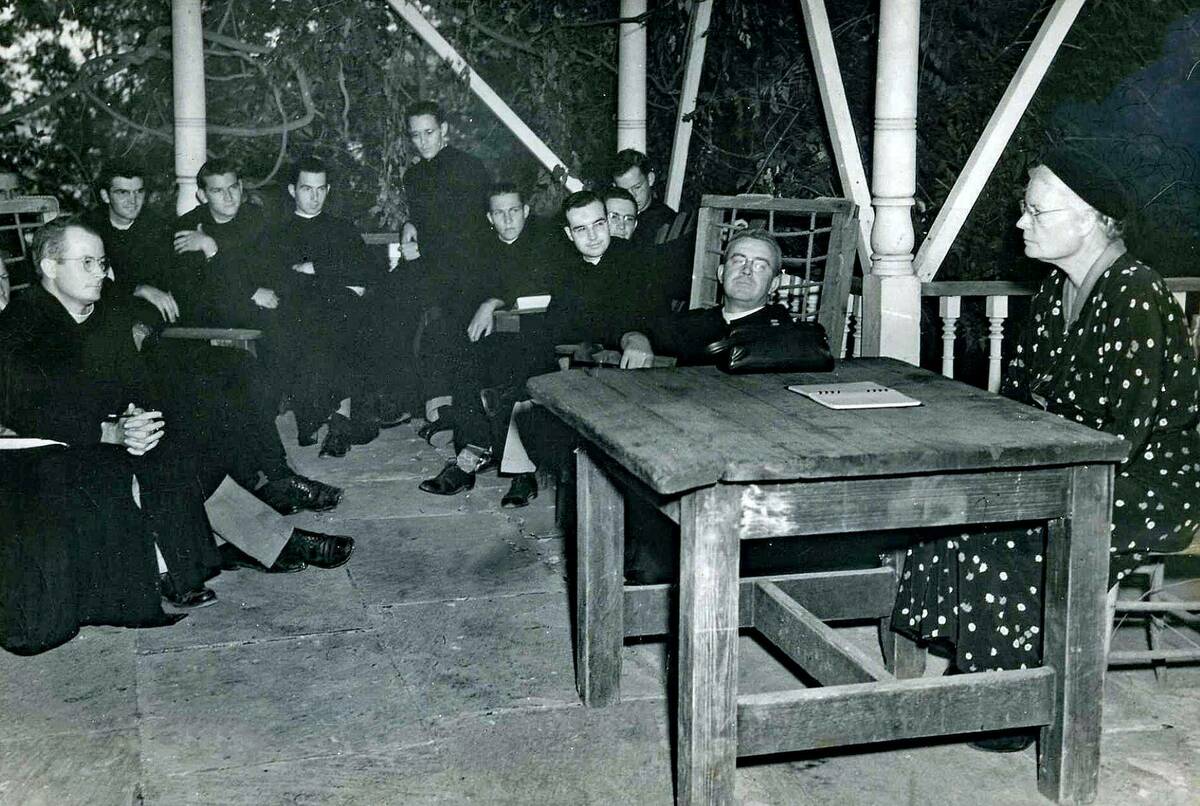

In the midst of all this, the authors of “Lament. Repent. Repair.” traveled to the New York Catholic Worker for a roundtable discussion on race in February 2018. This discussion—available on YouTube—opened with Joe Kruse of the Minneapolis CW standing up and declaring that Peter Maurin’s attempt to open a Catholic Worker in Harlem in 1934 was “a textbook example of a way in which racism is embedded” in the Catholic Worker, since his project had reproduced “a patriarchal white savior evangelism” and “reinforced the white supremacy” that Peter otherwise sought to challenge.[5] Later that year, racism in the Catholic Worker was the main focus of a national gathering of Catholic Workers who met in Rochester. And uproar over “Lament. Repent. Repair.” continued in online forums as well as in two additional editions of Catholic Worker Anti-Racism Review.[6]

This debate eventually made its way beyond the Catholic Worker movement when the June 2019 edition of Horizons published an essay by Lincoln Rice titled “The Catholic Worker Movement and Racial Justice: A Precarious Relationship.” Rice, who has a Ph.D. in theology from Marquette, is a member of the Milwaukee Catholic Worker, one of authors of “Lament. Repent. Repair.” and is the managing editor of the Catholic Worker Anti-Racism Review. In his essay, Rice argued that the view Day and Maurin held on racism “betrayed the notion that racism was only one among many social injustices” instead of, as Rice asserted, “a constitutive part of social injustice in the United States.”[7]

Rice repeated the claim that since World War II pacifism had become the central focus of the CW, overshadowing the anti-racism that existed early on in the movement, and even chasing away some anti-racist CWs like Arthur Falls from the movement (it was Falls who had suggested that Day change the masthead on The Catholic Worker to include a Black and white worker). “Unfortunately,” Rice asserted, “neither Day or Marin wrote or worked adequately against anti-black racism. They rarely wrote on it and it was not part of their central texts.”[8] And this omission, he declared, “has likely contributed to further omissions on the topic of racism by those who admire or participate in the movement.”[9] Rice went on to offer a detailed analysis of the number of times racism was discussed in the pages of The Catholic Worker paper over the decades to support his conclusion that Day and the Worker were not “passionate enough” about the issue.

As painful as it has been and continues to be for folks in the Catholic Worker, I think this debate is ultimately healthy and a sign of the vitality that still exists within the movement almost ninety years after its founding. These kinds of discussions certainly need to take place and from my own experience in the Catholic Worker, I know that such discussions are important. During my three years living and working in the St. Peter Claver Catholic Worker, I can remember being very aware of the fact that our community was made up largely of college-educated white people living and working in neighborhoods that were largely Black and brown. And this is certainly true of other Catholic Workers, though there are some important and impressive exceptions, such as the Catholic Worker community in Hartford. I am also very aware that in Peter Maurin’s telling of the history of Western civilization, the slave trade is never mentioned.

II.

I am no longer as active in the Catholic Worker as I would like, so I hesitate to enter this debate. Nevertheless, I think I can offer something that may be helpful to the movement and people I respect a great deal. One place is in regard to the term “anti-racism,” which since being popularized in Ibram X. Kendi’s book How to be an Anti-Racist, has come under increased scrutiny (often from Black scholars on the Left), and is perhaps a much more complicated and problematic term than the editors of the Catholic Worker Antiracism Review seem to acknowledge. For instance, the Columbia University linguist—a New York Times columnist—John McWhorter has described antiracism as a “new religion” with its own prophets, whom he refers to as “the Elect.”[10] These Elect see themselves as “bearers of a Good News that, if all people would simply open up and see it, would create a perfect world.” McWhorter noted that the Elect’s unshakable convictions have led them to persecute people with unfair and often blanket accusations of racism. Many of these inquisitions have not been leveled by Black or brown people but by white Elects themselves, who McWhorter described as carrying a kind of “self-flagellational guilt.”

University of Pennsylvania political scientist Adolph Reed has been even more critical of anti-racism, which he describes as a “neoliberal alternative” for the Left.[11] For Reed, anti-racism is “race-reductionism” premised on the belief that racism is the source of inequality. And such a belief, Reed argues, fits neatly within the worldview of Wall Street and Silicon Valley—whose titans certainly do not want to dwell on unjust economic structures and policies that have enabled the yawning global wealth gap to increase. And so corporations such as Amazon have been quick to embrace the rhetoric of anti-racism, as it is much more comfortable to denounce systemic racism than free-market capitalism or the conditions of Amazon workers.[12] Of course, a similar critique could also be made of the embrace of anti-racism within so-called “elite” universities in the US while avoiding discussion of their role in perpetuating social inequality—let alone how they acquired their multi-billion dollar endowments.

And the racist/anti-racist dichotomy also seems problematic theologically. Catholic metaphysics is not a simple two-tiered contrast between sin and the supernatural. Grace is understood to be beyond both sin and mere nature. And so, within Catholic moral theology, the Christian life entails something beyond simply avoiding sin. Being anti-racist, then, is much more than just not being racist. That said, at minimum perhaps a third “not racist” category is needed to better clarify this distinction. While more can certainly be said about such critiques, they do highlight the fact that a more reflective and self-critical approach to anti-racism by the authors of “Lament. Repent. Repair” and the Catholic Worker Antiracist Review is necessary.

Perhaps even more problematic, though, is the separation of issues of racial justice from US war-making that the authors of “Lament. Repent. Repair” make. While they acknowledge that racism was an important focus of the early Catholic Worker, the authors argue that once the focus turned to pacifism, racial injustice faded into the background. But this critique lacks a thick historical contextualization of the material—specifically, an appreciation of the background of the Old Left in the history of the Catholic Worker. As Maurice Isserman has argued in If I Had a Hammer, people of the Old Left—Communists, Trotskyists, anarchists of various stripes—fell into deep crisis from the 1930s to the 1960s and transmuted from a movement of political and economic transformation into a movement that embraced, for various reasons, pacifism.[13]

At the heart of this process was what Isserman called “the Americanization of Gandhi,” and among those he lists as key movements are the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and Congress of Racial Equality, along with key actors such as Howard Thurman, Bayard Rustin, and Martin Luther King, Jr.,—as well as Day and the Catholic Worker, especially their civil defense protests in the late 1950s and early 1960s. While Isserman’s history is certainly not without faults, it does explain the emergence of pacifism as a key theme and means of social protest and transformation, and one that should not be seen as being in competition with or an alternative to the work for racial justice. As Reed and Terrell pointed out, making a hard split between racism and war ultimately enables racism and calls for racial justice to be focused upon in isolation. As, for example, when the US military is held up for praise as one of the most racially integrated institutions in the US, while avoiding discussions of its use of torture or drone warfare on Black and brown people all over the world.[14]

Helpful in addressing this is the concept of racial capitalism, first articulated by Cedric Robinson in the 1980s and since furthered by scholars such as Robin D.G. Kelley and Jodi Melamed.[15] The idea of racial capitalism offers a direct challenge to Karl Marx’s argument that capitalism was some kind of a revolutionary negation of feudalism. Instead, Robinson demonstrated that capitalism emerged within the feudal order and so grew out of the cultural soil of a Western civilization already thoroughly infused with racialism. Capitalism, therefore, did not break from the older racially segregated world, Robinson argued, but rather it evolved from it to produce a modern global system of “racial capitalism” dependent on slavery, economic exploitation, imperialism, genocide, and war.

As Kelley explains, capitalism is “racial” not because of some conspiracy to divide workers or justify slavery or colonialism, but rather because the feudal system out of which it developed was already racially divided into racial identities such as Irish, Jews, Roma, Gypies, or Slavs.[16] In short, as Jodi Melamed explained, “capitalism is racial capitalism,” since “capitalism can only be capital when it is accumulating, and it can only accumulate by producing and moving through relations of severe inequality among human groups.”[17]

While largely ignored at first, this notion of racial capitalism has been revisited by activists in the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement, as well as by scholars such as Ruth Wilson Gilmore and other advocates for the abolition of prisons.[18] Even more recently, the Baylor University Religious Studies scholar Johnathan Tran employs racial capitalism in his book Asian Americans and the Spirit of Racial Capitalism. Since racial identities were created to serve capitalism, to discuss these identities in isolation from the political economy, Tran argues, ignores its fundamental link with capitalism.[19] Tran points to an “identarian antiracism” that has become the “orthodox” view in the academy which excludes not only any account of the political economy within which racial identities were purposely created, but also any serious engagement with religious traditions—other than to point out their role in institutional racism.[20]

I would like to suggest that this concept of racial capitalism can also be helpful for this debate within the Catholic Worker in overcoming the assertion that issues of racial injustice can somehow be separated from economic justice or pacifism. For Robinson and others, racism is not regarded as “a constitutive part of social injustice in the United States,” and so while racism can certainly be focused upon, it cannot be isolated from other social injustices such as war and inequality. In this sense, criticism of capitalism in the US is a critique of racism.

Likewise, criticism of US war-making—which “Lament. Repent. Repair” portray as distracting the Catholic Worker from issues of race—can also be seen as a critique of racism. As Brian Terrell and others have noted, the pacifism of the Catholic Worker has always highlighted the fact that America’s wars are racist wars, waged almost exclusively against non-white enemies.[21] Criticism of these wars, therefore, cannot somehow be separated from the racism underlying them.

While Rice’s painstaking analysis to determine whether Day was “passionate enough” about racism in the pages of The Catholic Worker is certainly impressive, it misses important points that these theorists of racial capitalism are making. More research into these questions is needed and my hope is that a better understanding of racial capitalism will facilitate this. It is also worth noting a recent article by Bailey Dick in American Catholic Studies that seems to challenge Rice’s claims that Day did not focus enough on racism.[22] From Koinonia Farm in Georgia in the 1950s (where she was shot at) to the Civil Rights protests in Danville, Virginia in the 1960s to the United Farm Workers strike in California in the 1970s (where she was arrested for the last time) Dorothy Day wrote about and published on racism throughout her life.

III.

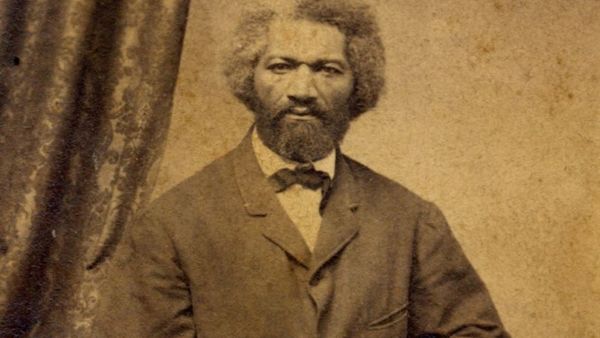

Beyond offering a snapshot of many of the discussions in US Catholic theology today, this discussion of racism and the Catholic Worker also presents an opportunity to clarify thought on what a Catholic response to racism could be. For instance, in his 2010 Presidential address to the Catholic Theological Society of America, Bryan Massingale suggested that Malcolm X was a “neglected ‘classic’ for Catholic theological reflection, an idea he expanded upon the following year at the American Academy of Religion with a paper titled “Toward a Catholic Malcolm X?”[23] But while Massingale focused primarily on Malcolm X’s critique that Christianity had failed people of color—a criticism Massingale made against US Catholicism in particular—he seemed to overlook what Malcolm X regarded as the solution to anti-black racism in the US.

Indeed, upon returning from Mecca in 1965, an experience recounted in his Autobiography, Malcolm X stated that his time on the Haj—witnessing the racial harmony among the pilgrims—opened his eyes. He came to see that it was not the white man who was evil, but rather it was the “American political, economic, and social atmosphere” that nourished “a racist psychology” in whites.[24] And Malcolm X was convinced that only an embrace of what he termed “Orthodox Islam” could overcome a racist US society and culture.[25]

Following Massingale’s lead, I would suggest that a Catholic Malcolm X would use the resources within Catholic tradition to critique “American political, economic, and social atmosphere” and the “racist psychology” it nourishes in whites—particularly white Catholics in the US—and in so doing, suggest that a response to racism could come in the form of a greater or truer faithfulness in Christ and the authentic teaching of the Catholic Church—what Malcolm X might have called “Orthodox Catholicism.”

Like Malcolm X, a Catholic Malcolm X would offer a consistent critique of American society and culture—particularly the political and economic institutions such as racial capitalism. And just as Malcolm X appealed to Islam, a Catholic Malcolm X could appeal to elements within Catholic tradition that could be marshaled to resist racism, and thereby try to move forward from what Arthur Falls called “a mythical body of Christ” to a truly mystical body of Christ—always seeking, as Dorothy Day extolled in the pages of The Catholic Worker, to build a new society in the shell of the old, where it is easier for people to be good.

[1] Jessica Coblentz, “Forgetting and Repeating the Theological Racism at ‘Theology in the Americas’” in American Catholicism in the 21st Century: Crossroads, Crisis, or Renewal? College Theology Society Annual Volume 63, edited by Benjamin Peters and Nicholas Rademacher, (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2018): 89–101 at 97.

[3] Brian Terrell “How the Catholic Worker is and isn’t an Institution and How an Anti-Racism Statement can be Racist” War is a Crime blog (posted February 15, 2019).

[4] See Mare Benevento, “Is the Catholic Worker a ‘racist institution’?” National Catholic Reporter (August 11, 2018).

[7] Lincoln Rice, “The Catholic Worker Movement and Racial Justice: A Precarious Relationship.” Horizons, 46/1 (June 2019): 53–78 at 62.

[8] Ibid., 67.

[9] Ibid., 64.

[10] John McWhorter, Woke Racism: How a New Religion Has Betrayed Black America (New York: Portfolio/ Penguin, 2021).

[11] Adolph Reed, Jr. “Antiracism: A Neoliberal Alternative to a Left.” Dialectical Anthropology 42, no. 2 (2018): 105–15.

[12] Gillian Friedman, “Here’s What Companies Are Promising to Do to Fight Racism” New York Times (online, August 23, 2020).

[13] Maurice Isserman, If I Had a Hammer: The Death of the Old Left and the Birth of the New Left (Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1987).

[14] Sujata Gupta, “Military towns are the most racially integrated places in the U.S. Here’s why” Science News (February 8, 2022).

[15] Cedric Robinson, Black Marxism: the Making of a Black Radical Tradition (Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 1983).

[16] Robin D.G. Kelley, Introduction to “Race Capitalism Justice” Boston Review (2017), 5–8 at 7.

[17] Jodi Melamed, “Racial Capitalism” Critical Ethnic Studies 1/1 (Spring 2015), 76–85 at 77.

[18] Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Golden Gulag (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007).

[19] Johnathan Tran, Asian Americans and the Spirit of Racial Capitalism, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2022).

[20] Ibid., 4

[21] See Julie Leininger Pycior, Dorothy Day, Thomas Merton and the Greatest Commandment: Radical Love in Times of Crisis (Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 2020).

[22] Bailey Dick, The Catholic Worker’s Coverage of Civil Rights and Racial Justice” American Catholic Studies 131/4 (Winter 2020): 1–31.

[23] Bryan N. Massingale, “Toward a Catholic Malcolm X?” American Catholic Studies 125/3 (Fall 2014): 8–11.

[24] Malcom X, Autobiography of Malcolm X as told to Alex Haley (New York: Ballantine Books, 1964), 371.

[25] Ibid., 339.