St. Bonaventure University is a Catholic liberal arts college in upstate New York. Run by the Franciscans, it is perhaps most famous because Thomas Merton once taught there. They deserve to be famous for another piece of history. For a period, they had a core program of studies that was the only one of its kind in the world.

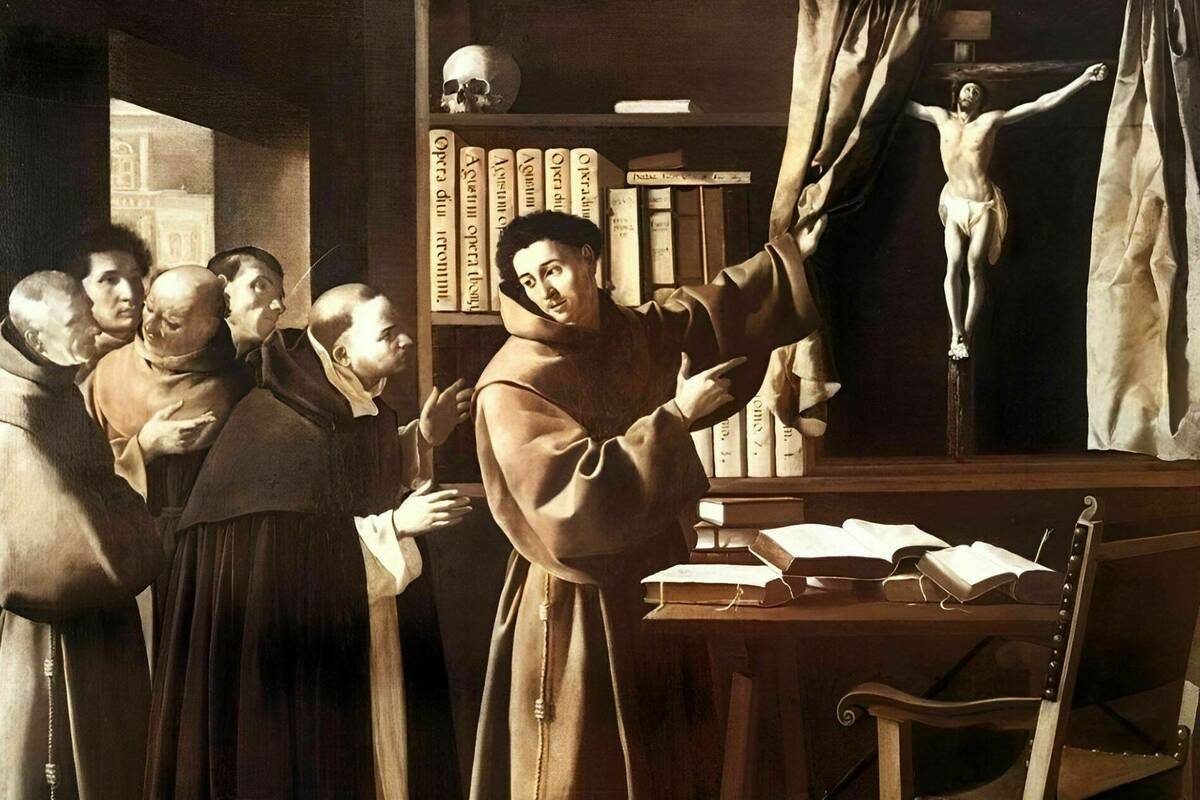

Following in the path of their namesake, they structured their core around the Itinerarium mentis ad deum, the journey of the mind into God. The original Bonaventure conceived of St. Francis’s vision of the Six-Winged Seraph as an account of the mind’s ascent from outward things to inner things toward higher things. In these courses, students were shaped by a Bonaventurian vision such that their education followed this path. In aiming for this educational course, what they offered was different than other Franciscan schools, from other Catholic schools, and from any secular university.

Alas, they gave up on this core and its delightful uniqueness. Students at Bonaventure still take an impressive class on the spirituality of Francis and Clare; but they gave up on a robust vision for a shrunken version of it, and the world became a little less diverse because of it. In what follows, I want to consider the question of Catholic institutional identity and discourse around diversity. Specifically, I argue that too often in giving up on or reducing our institutional identity we undermine actual (intellectual) diversity even while we talk more about diversity.

More Difference but Everything Is the Same

Bland sameness afflicts much of life today. Wherever one turns these days, it is hard to miss some institution proclaiming its commitment to diversity. Businesses, the military, churches, and, especially, universities all claim to be diverse places. Behind these identical claims to difference there is a rush towards sameness, a rush that is particularly acute at the university level. As colleges have become corporatized and monetized, they have also suffered from an intense drive towards institutional uniformity while proclaiming diversity. Every school claims to prioritize STEM (but not really the Math part), has rapidly growing business programs, and sports some kind of slogan about change or progress. They hire the same marketing firms to design the same brochures telling you how unique the school is.

The most important expression of this uniformity is in the elimination, or diminution, of university cores. These used to be the heart of an institution and were the distinguishing mark of the institution. Instead of a distinctive core, many have switched to GenEd requirements. Is there anything more uniform than GenEd? Students receive a scattering of courses in random subjects in a way that ends up looking the same everywhere and never obstructs the central work of producing employees for corporations.

The elimination or diminution of core requirements has overtaken many Catholic colleges too. These should be places where students encounter ideas and traditions of thinking that are different than at other schools. This difference is particularly affirmed and explored through philosophy and theology requirements. On campuses particularized by friars, sisters, and priests, students should bustle into the classroom to find the ever-living theological ideas. What they should find there, even if they grumble about it, they will not find at more prestigious Ivy League schools or less expensive state schools. To attend a university that requires you to probe the five ways, to revive your restless heart, to develop a politics centered on the preferential option for the poor, and to examine the visible signs of invisible realities is to attend a university that is different.

But far too many Catholic colleges have fled from this difference. Bonaventure is not unique in this. St Anselm College, a Benedictine college in New Hampshire, had a stirring two-year core centered on great figures, looking to exemplars of humanity—saints, poets, thinkers, and artists—to offer students a chance to envision a life that transcends the immanent frame. Alas, they set it aside for GenEd’s and some philosophy and theology requirements.

Often the flattening of difference is preceded by the elimination of theology. Fairfield University—rather than being different than nearby UConn—has a Religious Studies Department instead of Theology Department. Having moved away from the Scientia Divina and rejected a specific intellectual tradition, they instead study religion as a “human phenomenon.” Abandoning the sacred science of theology undermines their new core. Named, "Magis," it should mean more or great and should evoke the Ignatian motto ad maiorem dei gloriam.

No longer giving glory to God in their theological studies, the core does not propose a specific vision of the greater. Instead, it “engages students to establish their own values and understanding of the world.” Will these values and understandings be different than if they had landed at Yale or UConn? I doubt it.

Catholic colleges will always have a lot in common with other schools, as Gravissimum Educationis teaches: “No less than other schools does the Catholic school pursue cultural goals and the human formation of youth.” That being said, Catholic schools have a task that is proper to them. This proper task gives the Catholic school its distinctiveness.

[Their] proper function is to create for the school community a special atmosphere animated by the Gospel spirit of freedom and charity, to help youth grow according to the new creatures they were made through baptism as they develop their own personalities, and finally to order the whole of human culture to the news of salvation so that the knowledge the students gradually acquire of the world, life, and man is illumined by faith.

The Council fathers taught—and alas have too often been ignored by universities—that this proper task requires Catholic philosophy and theology, a strong sense of the Scholastic tradition (with a legitimate primacy to Thomas), an education cognizant of the gift of sexual difference and complementarity between men and women, and a robust sense of the formation of students according to Christ who is the paradigm of humanity. They held that in doing this, Catholic schools build up “the earthly city” and offer a “public and enduring influence” while acting a “saving leaven in the human community.” Living their different identity, they foster the rich pluralism of diverse societies while offering a vision of the fulfillment of their societies in the City of God. Being different is their service to the world. When we give up that difference by giving up our identity, we cannot promote actual pluralism and cannot really offer the news of salvation or illumine the world through faith.

Thinking Sameness and Difference

People must have an identity first before you can speak of a diversity of people. Diversity as a form of pluralism requires distinctiveness of individuals. Were the individual objects in a set to be identical, then there would be no diversity, just mere multiplicity. The same goes for education. Higher education’s uniform proclamation of diversity too often corresponds to a downplaying of institutional identity. When St. Bonaventure ended its distinctive core, one professor celebrated the change because he “liked that students have to take courses related to diversity and the study of human difference.”

What seems to have actually happened is that diversity and human difference was lost in the process. The decreased institutional identity (or lack thereof) means there is no institutional diversity between universities. If we are to have institutional diversity in higher education, then colleges, especially Catholic ones, need to make a commitment to being a certain kind of school, especially in their core courses and theology departments.

To make a commitment to something is to choose the one from among the many. To commit to this rather than those is to recognize a real difference between what you have chosen and what you have not. To do so rationally is to be able to articulate why you think your selection is the right one amidst all the others. To commit thoughtfully is to “be ready to give an answer [apologia] to anyone who asks for the reasons for your hope” (1 Pet 3:15).

Here, difference is maintained by the particularity of commitment. Reasoned discourse expresses this difference with those who have differing commitments. In contrast, to choose everything is to choose nothing and thus to be unable to articulate the difference between the things you have not chosen. If you are not distinct, you do not need an apologia for your commitments because you are the same as everyone else.

Commitment is not easy. It can be hard to see the right thing to believe or the right course of action to pursue. In part, it can be hard to see the difference between things. It is also hard to commit to something because it requires giving up other things. All commitment is a kind of ascetic practice in that it requires sacrificing other options. We can see this is in the asceticism of marriage. Foregoing all others, you commit to this one person. Your commitment is not primarily a rejection, but it does bear with it that rejection. “No one else but you” we say on our wedding days in part because the “you” is lovely beyond any other. Marriage discloses the joy and freedom of commitment. It frees us from the anxiety and loneliness of having everything, which is another way of having nothing.

If Catholic universities are to avoid the nothingness of being everything, they need to commit to their Catholic commitments. Restoring these commitments is a recovery of the source of the Catholic college’s specific mission within the context of the shared mission of Catholic education. St. John Paul II taught that “the source of its unity springs from a common dedication to the truth, a common vision of the dignity of the human person and, ultimately, the person and message of Christ which gives the Institution its distinctive character.” The distinctiveness of a Catholic college disappears if it detaches from this source and accedes the sameness-making diversity that occupies too many institutions.

Catholic universities, in losing their identities, tend to slide into the difference-minimalizing tendencies of liberalism. As philosopher D.C. Schindler writes, “Rather than recognizing difference as real, good, and significant in its difference, the liberal notion of diversity seeks to respect all possibilities by minimizing the significance of difference, trivializing it with respect with things that really matter.” There are no reasons to commit to one belief system rather than another and thus no likely reason you would shape your educational system around a specific core or theological tradition. Rather, we are presented with “options” to try on and discard. What we never do is commit to one and thus consider it not as an option but as the truth. Everything becomes valid and so reasons for one thing rather than another are impossible to present. Without such serious study, beliefs become like people on Tinder. Swipe right to “establish your own values” without being able to give an apologia for your choice.

Our universities too often express this non-committal sameness masking itself as diversity. Having “committed” to diversity, they say the same things about diversity and offer the same education as any other universities. To say something different, or educate in a unique way, would require committing to something as good and true for each and for all. As Schindler writes, “genuine diversity implies a principle that holds things together in their difference.” In other words, to genuinely commit to a vision of the good life and an educational program that is fitting for this vision would be to take difference seriously. Without this, we get the “endless repetition of the same.” It is like having every tone of music at the same time. You get neither cacophony nor harmony but a mere droning.

Aiming for Unity and Getting Diversity Thrown In

C. S. Lewis claimed that when people “aim for heaven” they get “the earth ‘thrown in,’” whereas when “they aim for earth they get neither.” Consider the medieval cathedral builders or the builders of the great mosques of the Arab world. Their builders, in aiming for heaven, created an earthly expression of heaven and created something far more distinct than a McDonald's.

Now, consider marriage. To commit to this one person reorders your relationship with others. It grounds one in a new network of relations with your in-laws, children, and with other couples and their kids. You are freed for friendship with people of the opposite sex because those relations are unfettered from the potentiality of romance. Having made this one commitment to this one person makes your whole life more plural. Aiming for one person, you get everyone “thrown in.”

What is needed for institutional diversity is not primarily aiming for diversity but aiming for the true and good as best you understand it. Real pluralism arises from the commitment to truth and goodness, aiming for something not because it differs but because it is the right thing to aim for. This will lead to starkly different views, but in a more honest way that respects the views as different. Negotiating and contesting these differences is not easy. Giving reasons for your hopes while listening to different reasons for different hopes is hard. Hearing and encountering other peoples’ reasons and hopes is hard too. But then human pluralism is hard. It is also good. Real liberalism fosters this on individual and institutional levels. If we want the pluralism of liberal society, then we caretakers of educational institutions, especially Catholic ones, need to make our difference known.

Rich pluralism also arises within a unified tradition. We see this in Catholic religious life, which did not arise because Benedict, Dominic, or Dorothy Day were trying to be diverse. They were trying to live out the Gospel and ended up instantiating robust, new, and varied forms of life along the way. We should not be surprised that the most diverse community—in forms of life, intellectual practices, and ethnicities—is the Catholic Church. Aiming at the universalism of the Church means getting her pluralism—and even her parochialism—thrown in. “Here comes everybody,” as James Joyce put it.[1]

What to do then if you hope to revive diversity in higher education? Aim for the true and good. In so aiming, cultivate the practices of disputing the true and good. Do this whether you have determined your deepest convictions or whether you have not. Such disputations highlight the inherent meanings and structures of a belief, and thus disclose the reality of differences.

This is why the medievals cultivated disputations: the intellectual practice of questioning and arguing about their deepest beliefs about reality. Aquinas was unafraid to ask if God exists and to argue out the objections. Seeing the objections and replies makes the “I answer that” matter in its contradistinction to the objections. It discloses the truth so that we can commit, understand our commitment, and educate others into that commitment. Catholic universities should be places of identity and plurality because of the inherent need for both from within the Catholic intellectual commitment to the unity of truth and the reality of the common and highest good.

We ought then to further inhabit our traditions and to do so well. This means delving into the tradition “to bring forth things old and new” (Matt 15:32). In delving into that tradition, we will inevitably engage in the contest with other traditions. But if Catholic institutions do not seriously explore the Catholic tradition, no one else will. If Catholic educational institutions do not live these traditions of thought in our educational programs, they will not live on in other educational contexts. We are the only ones who will tend the fire of our intellectual tradition.

We do not have to be monolithic and closed like many secular schools are while pretending to instantiate pluralism. We should give our students a running debate between Aquinas and Rawls, Nietzsche and Pascal, or Dorothy Day and Machiavelli. In so doing, you will give students a chance to actually know a tradition through seriously engaging different traditions. You will also end up offering a richer education than the neighboring Catholic school that has forgotten there is such a thing as Catholic tradition and so also forgotten about pluralism itself. Such a forgetting leaves their own tradition insufficiently challenged and thus itself insufficiently understood.

Recovering Sameness and Difference

In recent years, there has been a resurgent interest in the metaphysical categories of transcendentals. These transcendentals run through all existing things but also transcend each existing thing. The popular ones are the good, true, and beautiful. But a revival of higher educational diversity and of Catholic identity requires a recovery of the transcendentals of sameness and difference. Our bland diversity efforts claim difference and reject sameness. What we get instead is sameness without difference, but such that we are unaware of it. To see the metaphysical, ethical, and political centrality of sameness and difference is to recognize the difference that difference makes and to know the codependence of robust identity and real plurality.

Were we to restore robust theology and philosophy in our cores, we would rediscover how things can only exist and be understood because of the play of sameness and difference. Both transcendentals are expressions of the creative power of the God who made difference by creating the difference of creation from himself. In so doing, he created a universe and a humanity of staggering variety and saw that this variety grounded in his unity was very good.

Knowing this difference grounds any real thinking and thus any real education. Such an education is an introduction to the good, the true, and thus the beautiful. But it is also an introduction to encountering the play of unity and plurality. We will not encounter that play if Catholic university stops being different and thus stops offering students cores that ground them in a Catholic commitment and tradition while offering them a chance to think through that tradition in dialogue with others.

To embrace the transcendentals of sameness and difference is to encounter the dappled beauty of reality and to ascend through it, like Bonaventure, to the triune unity that sources that diversity. What else is education than this encounter enabled by the engagement with tradition in pursuit of the good and true? If Catholic universities and educational institutions are to be unique—and so promote diversity—they will need an education grounded in this encounter with a plural unity.

They will be different than Yale, Princeton, UPenn, or UConn, but that difference is good for society with its many traditions and for the specific Catholic college with its own specific tradition. The goodness of this kind of Catholic education is that Catholic schools should affirm “the unity of all truth.” This affirmation is a journey into the wild diversity of being which originates and ends in the highest truth and goodness that is God.

This is the beauty and singular insight of Gerard Manley Hopkins’ poem “Pied Beauty,” which should be required reading for Catholic schools considering both identity and diversity. The real diversity of “All things counter, original, spare, strange” arises out of the One God who “fathers forth” diversity out of his Triune Unity. In a strange sense, our dappled beauty becomes less dappled when we forget the One “whose beauty is past change.” In life and education, if we aim for that diversity and dappledness without unity beyond change, we will get neither. But if we aim for that Unity that fathers forth “whatever is fickle, freckled,” we will get all the beautiful diversity in the world thrown in.

[1] Long before Joyce, Augustine had something similar to say about the pilgrim city as a unity capable of gathering all diversity. “While it sojourns on earth, calls citizens out of all nations, and gathers together a society of pilgrims of all languages, not scrupling about diversities in the manners, laws, and institutions whereby earthly peace is secured and maintained, but recognizing that, however various these are, they all tend to one and the same end of earthly peace.”