We declare to you what was from the beginning,

what we have heard,

what we have seen with our eyes,

what we have looked at

and touched with our hands,

concerning the word of life—

this life was revealed, and we have seen it and testify to it,

and declare to you

the eternal life that was with the Father and was revealed to us—

we declare to you what we have seen and heard

so that you also may have fellowship with us;

We are writing these things so that our joy may be complete.

(1 Jn 1:1–4)

There are those beautiful, singular memories from childhood that sear into your brain, sticking with you for mysterious, inaccessible reasons. Some of them are quite insignificant, and when they roll around into the conscious forefront of my mind at odd occasions, I never cease to wonder at what odd chemistry of impressionability and emotional resonance has caused them to be burned into my memory.

As I was studying for my Scripture class during last finals week, I kept thinking of a particular, peculiar, very small memory that—at least for now—has been indelibly inked into my memory.

One long Minnesota February, the suburban homeschool co-op that my mother founded hosted art classes for several successive Saturdays. I remember the sacred pilgrimage to Michael's to buy Prismacolor pencils, the injunction to keep them in their own special box. These were not to be mixed into the catchall box filled with miscellaneous Crayola and Rose Art pencils that was a fixture of the "art project center" in our basement playroom. These pencils were special, and must be treated with reverence. I was delighted with these glamorous new Prismacolor pencils, bewitched by the dazzling excitement of taking a "real" art class, and eager to be inducted into the mystery of paintbrushes and ink, to learn the secret arts of mixing colors, forming shapes, and shading objects.

One morning, the lesson on ink drawing, I decided to draw a simple scene of the Resurrection. So I mixed together what I knew were ingredients of that Easter Sunday morning scene: angels, women, stone, tomb. Simple enough, right?

I brought forward the ink sketch to show the instructor, who was a kind fatherly man, with a mustache reminiscent of Tom Selleck's or my Uncle Randy's, and I will never forget his response: Which Gospel is this from?

Good Catholic child that I was, I had no idea that the Gospel accounts of Jesus' Death and Resurrection contained variations, my goodness. I had drawn two angels at the tomb (because that seemed right), and a cozy musketeer troop of three women with precious ointments, because I fuzzily recalled hearing in church of two of the ubiquitous Marys in the Resurrection roll call, and a Salome sandwiched between them. I thought these elements were Gospel truth, but I had apparently constructed my own artistic version of the Diatesseron!

It couldn't be Mark, Tom Selleck the Art Teacher began to run through his mental rolodex of the Resurrection accounts out loud, because in Mark there were three women but only one man, and in Matthew there were two women and one angel, and in John there were two angels, but only Mary Magdalene!

My wonder at the news that the Gospel accounts were not carbon copies of each other was subsumed by my wonder at this guru of a man who actually knew the differences. By heart. He could actually distinguish between the stories of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. To my nine-year-old self, this was sheer magic.

My memories of that narrative are spiked with small veins of childish self-righteousness. There is no one with a keener sense of fairness than a child, and I felt that it was pretty ghastly unfair for an art teacher to be commenting on the scriptural faithfulness of the content of my small drawing instead of the merits or demerits of the ink lines themselves.

But more than a slightly bruised pre-pubescent ego, my memory of that moment is wonder—one of those cliché, but never hackneyed, light bulb moments teachers are always on the lookout for, when a whole new way of looking at the world explodes into a child’s field of vision. I can still remember the awe that man's words imbued in my small heart, as I witnessed this expanding horizon open up my small world. There was a lot more in this Bible book than I realized. And there were real-life, regular, non-priest people like this art teacher who knew a lot about it.

Isaac said to his father Abraham, “Father!”

And he said, “Here I am, my son.”

He said, “The fire and the wood are here,

but where is the lamb for a burnt offering?”

Abraham said, “God himself will provide the lamb

for a burnt offering, my son.”

So the two of them walked on together. (Gen 22:7–8)

An analogous moment occurred several years later in the ninth grade, when I realized that the Genesis promise of the lamb of God to Abraham wasn't actually fulfilled. Because God didn't actually send a lamb to Abraham and Isaac even verses later. He sent a ram, which is a sorry substitute for a lamb. Thus, a new arch of dramatic tension was born, and a new horizon opened up.

Suddenly, the pathos and the drama in which this entire book was dripping struck me. A building tension was wound up in these stories whose crescendo was so expansive and majestic it hurt your heart. Oh. This is a drama of Salvation History. This is a German Romantic quest for the Lamb, full of angst and Sehnsucht. How long, O Lord, how long? Opening a Bible felt like opening a symphony, whose crying violins yearned for the long-looked-for Lamb in a world of rams.

We declare to you what was from the beginning,

what we have heard,

what we have seen with our eyes,

what we have looked at

and touched with our hands. . .

An analogous moment occurred many times over this semester in my class on the Gospel of John: learning the world of final redactors, source criticism, sign sources made this book more mystical. Digging through the historical realities of the text did not diminish its wonder, but deepened it to an infinite pitch.

For with each revelation—the unique dating of John's Passion narrative vis-à-vis the Synoptics; the contradictions woven into the text by a faithful, but mysterious, final redactor; the elegant stitching together of the Bread of Life discourses; the mysterious identity of the disciple whom Jesus loved—the fourth Gospel became a rich tapestry of word and light.

I realize that too many of my childhood first encounters with the Gospels were never with the actual books themselves—strange, wild, untamable beasts that they are—they were with declawed abridged versions, jarring sentences omitted, the original story filtered through the eyes of an interpreter. Or with the children's synopses of the life of Jesus that blend two accounts and muddle them together, or change conflicting details, confusing them so they are forced to harmonize, with mixed success—like forcing the twin poles of magnets to touch.

The reality of the mystery the Gospel celebrates is mediated to us in the mundane and hazy details of un-dateable papyri, of ancient codices, of original authors, of sources of tradition, of layers of redaction. But these details do not bog the narrative down in clunky exterior ornamentation, until we have lost the forest through the trees; rather, they illuminate the rich reality of the text.

For the truth of the Gospel, nostrae salutis causa, is of Godhead incarnate in real flesh and blood. Real flesh and blood is awfully, horribly messy. But, if there is one thing we can be sure of, it is that the Word is surely in the details: the beautiful, messy, mundane details of the story whose factual occurrence is lost to history, but whose truth is preserved in the work of memory and commemoration.

Our journey with the Gospels is forever to be our journey from understanding their image dimly, as in a child's ink sketch, to coming face-to-face with the grand epic of this story, imagining it in its full, messy incarnation in human, historical detail, redactors, translation errors, warts and all.

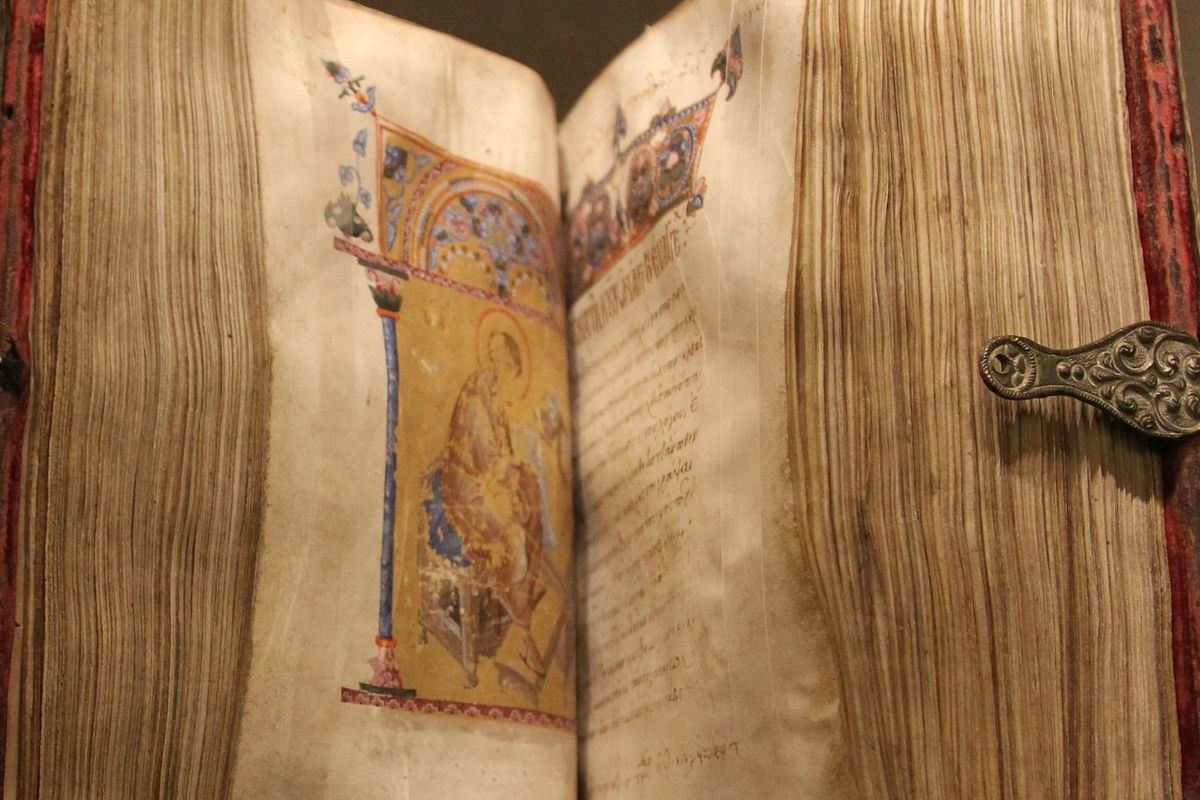

Featured Photo: Book of the Gospels by Tilemahos Efthimiadis; CC-BY-NC-ND-2.0.