How Catholics would respond to what historians sometimes term the Age of Democratic Revolutions was not obvious. Between the American Revolution in the 1770s and various European revolutions in 1848, at least twenty democracies sprouted (and withered) on both sides of the Atlantic.

Because so many ultramontanists, beginning with Joseph de Maistre and continuing through authoritarian Catholic leaders in the 1930s, voiced skepticism about constitutions and republican government, historians have neglected a wider Catholic political repertoire. Just as an “uncompromising Protestantism” could support democratic nationalism in early-nineteenth-century Britain, the Netherlands, Prussia, and the United States, so, too, did Reform Catholics support constitutions and representative governments from Spain and southern Italy to Mexico and much of Latin America.

An early indication that Catholics in southern Europe and Latin America were developing their own version of constitutional government became visible in Mexico. The first revolts against Spanish colonial rule began in 1810, with native-born priests leading an uprising not only in the realm of ideas but on the battlefield. After Mass in the village of Dolores, with the townspeople called into the main square by the ringing of church bells, Fr. Miguel Hidalgo organized an army eventually numbering thousands of men and dedicated to overthrowing the Spanish colonial government.

Placing an image of Our Lady of Guadalupe on the banners held by his troops, Hidalgo merged religion with a nascent Mexican national identity. He and his allies professed their loyalty to the Spanish king, Ferdinand VII, and their opposition to the putatively godless French who controlled much of Spain until 1814. But Hidalgo was also interested in Reform Catholicism. Educated by priests connected to Reform Catholic circles in Europe, Hidalgo came from an elite family and questioned papal authority, the virginity of Mary, and clerical celibacy. (He fathered several children with a succession of common-law wives.) Venezuela’s Simón Bolivar, another Latin American leader eager to end Spanish colonial rule in the region, thought Catholicism an “exclusive and intolerant religion.” But he envied how Hidalgo and “the leaders of the [Mexican] independence movement have happily profited from fanaticism with the greatest skill, proclaiming the famous Virgin of Guadalupe as queen of the patriots.”

Most bishops in Mexico, almost all from Spain, opposed Hidalgo’s insurgent army, some by excommunicating rebels and predicting they would go “infallibly to hell.” The influential Michoacán bishop, Manuel Abad y Queipo, despaired of Hidalgo, a friend, leading the rebellion and after his capture ordered his execution.

Still, only a year later, during the chaos created by Napoleon’s armies, an election was held in Cádiz, Spain, for a Cortes, or assembly. The Cortes retained the monarchy—although King Ferdinand VII did not attend its sessions—but proclaimed national sovereignty, civic equality, and universal male suffrage. The constitution drafted at Cádiz became influential not only in Latin America but also in Greece and India. Delegates claimed to transform Spain from a “Catholic monarchy,” to a “nation of Catholics.”

Deliberations in Cádiz resembled those in Paris in 1789. Priests constituted one-third of the delegates, their presence at a democratic assembly a symbolic rejection of the alliance of throne and altar so central to Spanish history. Some religious orders were abolished, again as in France. In Seville and other Spanish cities, much as in France after the Civil Constitution of the Clergy, Spanish citizens swore oaths of loyalty to the constitution after Mass and the constitution itself was read during the service. The Reform Catholic commitments of the assembly meant that delegates might discuss the relationship between the executive and the legislature on one day and ponder how to eliminate pilgrimages and prune overly exuberant devotions on the next.

Despite the enthusiasm that it generated, the Spanish constitutional regime of 1812 was short-lived. Napoleon’s defeat and the evacuation of the French armies became King Ferdinand VII’s opportunity, and he managed to restore the Spanish monarchy in 1814. Ferdinand VII reestablished the Inquisition and permitted the newly restored Jesuits back in the country. Mission campaigns began, and support for religious tolerance ebbed. One prominent Spanish ultramontane asked:

Are we in Spain, or in Holland and North America? . . . Which tolerance are we talking about? That of another religion, or that of people who are unfortunate enough to profess it? If we are speaking of tolerance of another religion, Catholicism is as intolerant as light is of darkness, and truth is of lies.

Another ultramontane writer took the time to condemn not just the standard villains of Luther and Calvin, but the Habsburg emperor Joseph II, Bishop Ricci, and other Reform Catholics for provoking the French Revolution and inspiring delegates at the Cortes of Cádiz.

Still, Reform Catholic ideas continued to spread across the Spanish and Portuguese empires. The first European to call for the independence of Latin American nations, a Belgian bishop, warned his readers that Latin American Catholics with “republican” sympathies would not listen to either Spanish Catholics opposed to liberty or “Rome and her thunders.” Bishop Queipo, in Mexico, had opposed Miguel Hidalgo’s populist revolt, but he also thought the 1812 Spanish Constitution “the most liberal, the most just and the most prudent” such document devised. A Reform Catholic bishop became the first president of Ecuador under its new constitution.

An unsuccessful republican revolt in Pernambuco, in northeast Brazil, in 1817 was often termed the “revolution of the priests” because of the participation of clergy trained at a seminary founded by a Reform Catholic bishop. The revolution’s leading figure melded science and faith by working as a botanist and a theology professor. Another leader of the Pernambuco revolt, Fr. Antônio Gonçalves da Cruz, met with the former United States president, John Adams. Adams had long scoffed at the idea of Catholics in South America supporting “free government.” More likely, he thought, to establish “Democracies among the Beasts, Birds or Fishes.” After meeting the congenial Gonçalves da Cruz, Adams wavered. Perhaps, he speculated, “the Age of Reason is not ended.” A Boston newspaper hailed Cruz as one of the “very patriotic” Catholic clergy, eager to “resist tyranny and establish liberty [just as] our clergy did in 1775.”

That the Spanish Constitution of 1812 declared Catholicism the state religion might seem puzzling. (It puzzled Thomas Jefferson, who admired the constitution but expressed disappointment at the “intolerance of all but the Catholic religion.”) After all, the same Cádiz assembly abolished the Inquisition in order to protect national sovereignty from Roman influence—this pleased Jefferson—and expelled the papal nuncio. And yet the constitution reads: “The religion of the Spanish nation is, and ever shall be, the Catholic Apostolic Religion and only true faith. The Nation shall, by wise and just laws, protect it and prevent the exercise of any other.”

In Haiti (1804), Venezuela (1811), Spain (1812), Naples (1820), Spain again (1820), Portugal (1822), and Mexico (1824), constitutions drafted in a Reform Catholic key defined Catholicism as integral to national identity. In Naples, legislators added the term “public” to the subsection on Catholicism as the national religion, implying that private practice of other creeds would not constitute a crime. Even this modification proved controversial and was dropped before the final vote. The Chilean Constitution of 1822 tolerated individual dissent from Catholicism only as long as it did not lead to “calumnies, affronts or crime.” Simón Bolivar judged religion an entirely private—indeed absurd—matter, but even Bolivar drafted a constitution for Colombia in 1828 declaring that “the government supports and protects the Roman Catholic Apostolic religion as the religion of Colombians.”

This melding of religion and the state occurred because Reform Catholic clergy and politicians assumed that religion needed to support the state, not be separated from it. In the eighteenth century, Reform Catholics had pledged their loyalty to royal authority as one means of unifying the state and checking the power of the papacy. In the nineteenth century, republican governments were substituted for monarchies in some countries, but the principle of integrating church with state remained. Bishops and clergy still sat in parliaments, swore in presidents, and dictated legislation on moral matters.

The desire to weave together Catholicism and the state rested in part on an absence of religious diversity. In southern Europe and Latin America, Catholics were the overwhelming majority of the population, often with over 90 percent of residents baptized. Contact with clergy might be episodic in rural regions but a Catholic culture was widespread. (The religions of enslaved people in Latin America were more diverse, but many enslaved people also identified as Catholic.) Even leaders of the Italian republics of the 1790s viewed endorsement of Catholicism as part of a “religious social contract.” A Benedictine monk elected to the Neapolitan parliament explained his preference for a state religion this way:

Having just the one religion, we do not need to proclaim freedom of worship, as other countries, where there are followers of different religions, have been obliged to do. Happy as we are to have this powerful bond, we will not live in fear of those bloody scenes between Catholics and Protestants witnessed even in recent years in France.

Small groups of Jews and Protestants lived in even the most Catholic countries, and Reform Catholics proved more accepting than their ultramontane Catholic contemporaries of this pluralism. One Protestant observer complimented a Portuguese bishop in Rio de Janeiro—where the constitution declared Catholicism the state religion—for being “perfectly and sincerely tolerant of every sect, while he is warmly attached to his own.” Even so, Reform Catholic leaders only accepted the rights of groups to worship, not the rights of individuals to proselytize. The same Uruguayan constitution that made Catholicism the official state religion carved out rights of worship for specific groups, such as Anglicans, Swiss German evangelicals, and Waldensians, but not freedom of religion for individuals.

Another liberal revolution occurred in Spain in 1820. Reform Catholics who had gone underground after 1814 resurfaced and began speaking again of constitutions and democracy. Fifty-four priests were elected to the reestablished Cortes, and priests explained the new constitution “to all their parishioners on Sundays and on festival days.” It still seemed possible that democracy could be supported by “the pure faith, without obstacles, without superstition or fanaticism.”

This second Spanish revolution of 1820 gave Mexican patriots the opportunity to declare their own country’s independence. After much turmoil, the republic established in 1824 exemplified Fr. Servando Teresa de Mier’s vision in that the constitution declared Catholicism the “religion of the Mexican nation.” All parishioners attending Mass in Mexico City on one October Sunday swore an oath to the constitution and listened as priests explained the document.

In Spain, democracy was again short-lived. The wily Ferdinand VII reclaimed his throne in the early 1820s, abolished the Cortes, and began imprisoning or exiling his opponents. His officers executed fifty priests supportive of the revolutionary government and now deemed traitors to the nation. Ferdinand’s allies accused Havana’s Reform Catholic bishop of supporting Bishop Ricci and the Synod of Pistoia. In neighboring Portugal, ultramontane Catholics argued that the appalling ideals of the French Revolution must not be allowed to corrupt “the best institutions” with “perversity, disorder and general annihilation.”

By contrast, Latin America had become a global leader in republican government by 1830, with male suffrage more widespread than in any other region. One of Fr. Mier’s protégés, José Luis Mora, perhaps the most important Mexican intellectual of the era, admired the constitutional reforms passed by the Cortes of Cádiz. He criticized the needless expenses of pilgrimages and popular devotions and republished in Mexico Reform Catholic texts first published in Spain. But Mora expressed grave doubts about the capacity of the church to adapt to the new world of constitutions and democracy. “Instead of inspiring youth with a spirit of inquiry and doubt,” he feared, “[Catholic clergy] will . . . instill habits of dogmatism and disputation.”

*

While Reform Catholics in Spain and Latin America launched democratic revolutions, the political implications of the ultramontane revival in northern Europe remained uncertain. Joseph de Maistre—skeptical of representation in both church and state—had no doubts. “To hear the defenders of democracy talk,” de Maistre mockingly explained, “one would think that the people deliberate like a committee of wise men, whereas in truth judicial murders, foolhardy undertakings, wild choices, and above all foolish and disastrous wars are eminently the prerogatives of this form of government.”

The Holy Alliance created at the Congress of Vienna in 1815 strengthened monarchical governments with strong ties to the papacy. Some Reform Catholic suspicions persisted, especially in the Habsburg Empire, where the emperor refused to permit bishops to travel to Rome for their ordination, since they might “return to their dioceses as Roman converts . . . doing more harm than good to church and state.”

Other Catholics had begun a reassessment. The French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars had demonstrated the dangers of revolution and the need to mobilize religious influence on behalf of newly vulnerable monarchies. The Austrian chancellor, Metternich, once sympathetic to Reform Catholicism, now saw an alliance with the papacy as crucial to stabilizing the Habsburg Empire and worked to diminish Reform Catholic tendencies at the royal court. Papal officials expressed delight that leaders such as Metternich “have realized that the best defense of their thrones . . . lies in the true religion, which makes subjects faithful to their sovereign.”

In Canada, Archbishop Plessis, of Quebec, instructed his clergy never to criticize the king or the parliament and warned against “the spirit of democracy [that] is wreaking havoc among us.” As he privately explained to the British governor general in a tone echoing Catholic defenders of monarchy in Europe, “our altars protect the Throne as the Throne protects them.” In 1819, Plessis and a group of clergy journeyed to a “degraded and degenerate” France and met with one of their heroes, Joseph de Maistre.

Catholics in the United States also responded to ultramontane signals. In the 1780s, Bishop John Carroll had expressed sympathy for Reform Catholicism, but he recoiled from the 1790 Civil Constitution of the Clergy as an effort to reduce religion by “a slavish obsequiousness to the civil power.” When contacted by Henri Grégoire in 1809, Carroll declined his request for cooperation out of distaste for “some of the principles avowed in the pamphlets and proceedings of what is called the Constitutional clergy.” He thought that “late and present events” merited caution and judged it more important to sustain the “independent jurisdiction of the Holy See and episcopacy.”

The brightest prospect for a unity of democracy and ultramontanism came from Ireland in the person of Daniel O’Connell, the most important Irish politician of the nineteenth century. O’Connell had fled his Catholic boarding school in Belgium during the French Revolution. He was horrified to meet Irishmen who, after witnessing Louis XVI’s execution, thought the deed justified “for the cause.” At the time, he later recalled, he “thoroughly detested the revolutionists and the democratic principle.”

But O’Connell’s views changed. Over the next three decades, O’Connell became an inspiration to Catholic democrats around the world. In 1823, he formed a new Catholic association that focused on a variety of issues, including British prohibitions on Catholic chaplains visiting prisoners, the paucity of Catholic burial grounds, and bias against Catholics in the armed forces and the judiciary. A “Catholic rent” of one penny per month paid to O’Connell’s movement mobilized the country’s peasantry.

The Catholic emancipation campaign led by O’Connell—demanding the right of Catholics to sit in the British Parliament without swearing allegiance to the king or admitting, as then required, that veneration of Mary and the saints was “idolatrous”—culminated with a victory in 1829. Parliament finally permitted Catholics to hold office not only in England, but also in Ireland, South Africa, and other parts of the British Empire. (Catholics in what is now Quebec and Ontario had long possessed this ability.)

Restrictions remained. Catholic students could enroll at Cambridge but were not allowed to take a degree; they could not even enroll at Oxford. Jesuits were banned from coming “into this realm” (although this provision was not enforced), and priests were not to wear habits “save within the usual Places of Worship of the Roman Catholic religion.” Still, the principle of Catholic participation in public life had been won. Reflecting on an electoral triumph in County Clare, O’Connell described election day as “in reality, a religious ceremony.” Priests marched with parishioners carrying banners with such messages as “Vote for our Religion.” Or as he concluded, “honest men met to support upon the altar of their countryman the religion in which they believed.”

*

Observing Daniel O’Connell in the late 1820s were an extraordinary trio of French Catholics. All would play significant roles in modern Catholic history, and their sympathy for democratic reform would demonstrate the uncertain political trajectory of Catholicism in the age of democratic revolutions.

The three friends or “liberal ultramontanists” were Charles Montalembert, a lay nobleman; Henri Lacordaire, a priest who would reestablish the Dominican order in France; and Félicité de Lamennais, a Breton priest. Lamennais was the leader, and his essays on religious belief in the aftermath of the revolution circulated across Catholic Europe, North America, and South America. Like de Maistre, with whom he cheerfully corresponded early in his career and whose Du Pape he praised, Lamennais initially defended monarchical government. The corruption of Reform Catholicism had led to the French Revolution and explained how a “Christian monarchy” had “degenerated into a democracy.”

Lamennais—again like de Maistre—did not begin with politics. Instead he rejected a Catholicism in any way subservient to a state or claiming independence from the papacy. This view ran against the grain in 1820s France, where the state still paid clerical salaries. Lamennais wondered how French bishops distinguished governmental endorsement from governmental oppression. After all, he pointed out, the same nominally Catholic French government proved willing to ban the Jesuits in 1828 and funded a “Ministry of Religion which works ardently to corrupt all sources of teaching.” The intertwining of church and state led to “pressure for a break with Rome and the establishment of a national church which would represent only folly.”

Lamennais knew that younger ultramontane clergy found government restrictions on parish missions patronizing. Who would evangelize a France drifting away from orthodoxy? Not timid bishops appointed by the state. “By binding the cause of religion inseparably to that of the Government which oppresses it,” Lamennais regretted, “they are preparing a general apostasy.”

Ireland seemed a happier case. Lacordaire admiringly termed O’Connell the “Pope of Ireland,” and lauded the Irish Catholic willingness to “defend and demand” their freedom. “Of all the populations of Europe,” Lamennais explained, “the most indigent is that of Ireland, and yet nowhere is religion more endowed.” O’Connell reciprocated by expressing disdain—“as a Catholic”—for a French church still submitting episcopal nominations for approval by government officials.

Lamennais also reconsidered what his ultramontane theology might mean for politics. Daringly, he became convinced that Catholicism needed open debate and freedom of religion to thrive and that the people needed the opportunity to vote for their political leaders. He rejected the instinctive ultramontane desire to support authoritarian monarchs against populist agitation, because it betrayed a piety and theology that claimed to respect the aspirations and struggles of common people.

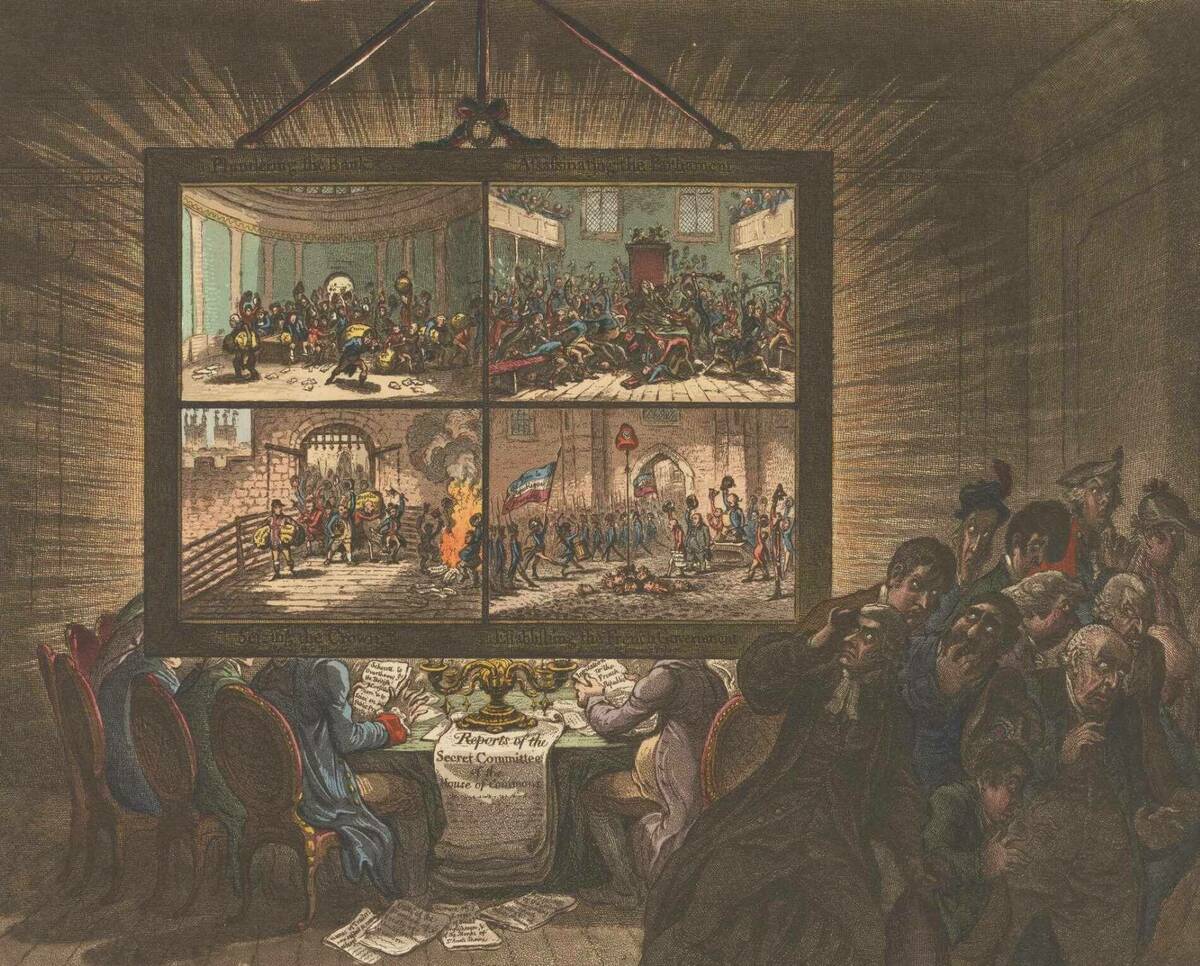

Lamennais’s opportunity to voice such views came during the European revolutions of 1830, a series of loosely linked revolts beginning in France but extending to Belgium, Poland, and northern Italy. As crowds again took to Parisian streets, Catholics with memories of the Terror in the 1790s trembled. (The archbishop of Paris hid in a convent.)

Lamennais thought the revolutions providential. The church must ally itself with the desire of the people for democratic government and basic liberties such as freedom of the press and freedom of religion. No longer should Catholics assume that monarchs in Paris, Vienna, and Madrid would shelter them from revolutionary storms. Better to welcome a “popular reaction against absolutism” and the collapse of a “worn-out order.” Watching from Ireland, O’Connell exulted in the idea that the revolution had dismayed “the tyrants and oligarchs of the world.”

Montalembert, Lammenais, and Lacordaire chose this moment to found L’Avenir (The Future), a newspaper emblazoned with the motto “God and Liberty.” In its eighteen-month existence, the journal circulated across Europe and North America with issues passed hand to hand. The editors insisted that the proliferation of constitutional governments around the world required “Catholics to give the world a model” of how to blend religious and political commitments.

The young ultramontanes paid special attention to Belgium and the United States. The influence of Lamennais in Belgium was strong, and Belgians elected a number of priests who admired Lamennais to the country’s first national assembly. The Belgian Constitution of 1830, drafted primarily by Catholics, granted freedom of religion to all citizens. “As in Belgium” became shorthand for the idea that Catholicism and republicanism could coexist. Lacordaire pondered leaving France to work as a missionary in the United States, since only in such a “free, populous, young” country could the “Catholic revolution” move in sync with the “political revolution.”

They also looked east. Polish revolutionaries launched a revolt against the Russian tsar in 1830, a challenge that generated enthusiasm around the Catholic world. The tsar’s crushing of the revolt meant a dispersion of Polish intellectuals, especially to Paris, where they quickly attached themselves to the liberal ultramontanes. Montalembert championed a “free and Catholic” Poland in the name of “Catholics of France.”

Crucially, these liberal ultramontanists saw no future for Reform Catholicism. At one time an alliance between the two impulses, both in their own way committed to a Catholic foundation for republican government, seemed possible. O’Connell welcomed the revolution that toppled Ferdinand VII in Spain in 1820 as an “auspicious circumstance.”

But different theological assumptions prevented a united front. Reform Catholics deplored an intrusive papacy, while liberal ultramontanes saw the papacy as protection against intrusive governments. O’Connell became disenchanted with the anti-papal contours of the revolution in Spain. In a speech that infuriated Spanish exiles in London, O’Connell denigrated “the attempts of the Cortes to ingratiate themselves with the English Liberals and their press.” He compared them with French revolutionaries during the 1790s and wondered if they desired the “overthrow of the Catholic religion.”

Ultramontane scorn for Reform Catholicism also became visible in France. When Henri Grégoire lay dying in 1831, one of the few surviving members of the constitutional clergy and the symbol worldwide of the Reform Catholic tradition, the archbishop of Paris refused him the last sacraments unless he renounced his forty-year-old endorsement of the Civil Constitution of the Clergy. (Independent to the end, Grégoire refused. The first sentence of his will blasted “ecclesiastical [and] political despotism.”) Montalembert mocked Grégoire’s supporters. “Earn the salary the government has thrown to you,” he sneered, “kiss the rings of the government-appointed bishops.” In Haiti, by contrast, where Grégoire had long been admired for his opposition to slavery and his Reform Catholicism, his death was marked by a national day of mourning.

The prospects for an ultramontane version of democracy soon dimmed. Knowing that many French bishops despised L’Avenir for its attacks on the episcopacy, Montalembert, Lamennais, and Lacordaire traveled across the Alps in 1831 as “pilgrims of God and liberty” in order to persuade the pope of their orthodoxy.

While they awaited an audience, the Polish community in Rome welcomed them, bestowing upon Lamennais a chalice in gratitude for his advocacy of their cause. Ominously, Gregory XVI chose this moment to condemn the Polish revolt against the tsar as an unlawful rebellion against a legitimate ruler. This papal edict shocked Polish Catholic rebels but also did not augur well for Lamennais, on record as calling the tsar a despot.

Perhaps Lamennais should have expected as much. From the first days after his election in 1831, Gregory XVI had struggled to quell a revolt in the northern sections of the Papal States, the portion of the Italian Peninsula governed (ineptly) by the Holy See. He had initially welcomed some of Lamennais’s ideas, and the shocked representative of the Habsburg Empire to the papal court reported hearing curial officials deem some revolutions “justified as Catholic causes.” Papal government must be saved “from itself,” Metternich bluntly responded. He knew that Lamennais had found a ready audience among some Catholics in Turin and other parts of northern Italy.

What Gregory XVI could not countenance was revolutionary nationalism. Out of desperation, Gregory XVI permitted Metternich to send the Austrian army to quash the revolt in northern Italy. Metternich also complained about L’Avenir to Rome and used his spy network to swipe Lamennais’s letters (where Lamennais bemoaned the intrigue surrounding the papal court) and send them to the pope with his own annotations. Representatives from the governments of Russia and Prussia also lobbied Gregory XVI, unhappy to see any Catholic journal countenance revolution and worried about restive Polish and German Catholic populations within their midst. The Irish priest Paul Cullen, one of Gregory XVI’s colleagues from their days of working together in the offices of the Propaganda Fide, characterized the revolutionaries this way: “irreligion in its broadest sphere, the vilest hatred against the Catholic religion and especially its supreme head the Pope, a desire to overturn all established authorities, and to destroy all order.”

Entreaties from the great powers made Gregory XVI less inclined to support Lamennais, but so, too, did the dossier compiled in the Holy Office. It included a defense by the foremost Italian disciple of Lamennais, Gioacchino Ventura, who described him as a writer of the “first rank.” Lamennais in this reading had demonstrated to Catholics around the world that the church did not invariably stand for the “despotism of kings” at the expense of “political liberty.” Other consultants were less admiring. They deplored the “disastrous” doctrines of Lamennais, allegedly imbibed from Voltaire and Benjamin Franklin. Popular sovereignty might work for a “Protestant people” accustomed to a society where each person is his or her own arbiter of the law, but not for a “Catholic people” faithful to compacts with king and God.

After struggling for months to gain an audience with the pope, only to be baffled on the occasion by desultory chitchat, Lamennais retreated from Rome to Munich. During a banquet in his honor, he was handed a fresh-off-the-press copy of Gregory’s XVI’s 1832 encyclical, Mirari Vos. Here Lamennais encountered ultramontanism shorn of democracy and civil liberties. Gregory XVI held that freedom of conscience was liable to “spread ruin.” Freedom of the press seemed “monstrous” because of the propensity to equate truth and error.

Lamennais and the other young ultramontanes initially thought they should submit to the encyclical and continue their work. Surely the pope’s words did not possess a “dogmatic character.” The pope, Lamennais thought, “is a good monk. He knows nothing of the world. He has no idea what the Church is like.” One Belgian disciple agreed that the pope referred to Lamennais in “only a few passages,” but he still worried about the “effect it would produce in France, in England, in Ireland, in Germany!”

So Lamennais kept writing. In 1834, in another messianic best seller, he again celebrated “liberty” and mourned those who think “the people are incapable of understanding their own interests.” Gregory XVI reciprocated by denouncing Lamennais, this time by name. The bishop of Rennes forced Lamennais’s brother, also a priest, to disavow him. In Quebec, onetime admirers of Lamennais took their papal cues and prohibited “anything [being] taught of the books, system or doctrine of that Author.” Rectors snatched issues of L’Avenir out of seminary libraries.

An embittered Lamennais now publicly denounced the “horrible system of [papal] tyranny which today burdens the people everywhere.” He told a colleague that the church “was in a state of complete decadence.” Friends pleaded with him to recant. “All agree that deplorable procedures have been used against you,” one explained, “but all agree that you have lacked humility.” Lamennais did not agree. He abandoned Catholicism and confessed to Montalembert to having long held “very great doubts on many points of Catholicism, doubts which have become stronger since.”

One of Lamennais’s correspondents during these fateful days was Giuseppe Mazzini, the world’s foremost advocate of democratic nationalism. Mazzini founded the “Young Italy” movement just after the revolutions of 1830, and the term reflected his desire to replace the Old Europe of treaties between popes and kings with republican governments. “We will not attempt any alliances with the kings,” he announced. “We will not delude ourselves that we can remain free by relying on international treaties and diplomatic tricks.”

Lamennais’s influence on Mazzini was immense, and references to the Breton writer’s “inspired pages” peppered Mazzini’s prose. Both men shared an antagonism toward Catholicism in its conservative, ultramontane form, and this clash between ultramontanism and liberal nationalism would soon become a fundamental organizing principle of the nineteenth century. Mazzini invoked the Reform Catholic hero, Bishop Ricci, as an intellectual ancestor who recognized the need to “establish the [principle of the] supremacy of the whole church over the pope in order to save . . . Christianity and religion from the ruin that threatens them.”

To Lamennais he was more direct. “The Rome of the Pope condemns you,” he confided. Only “the Rome of the people will succeed.”

*

Gregory XVI had denounced Lamennais, but the dream of an ultramontane democracy did not die. Henri Lacordaire, another of the French liberal ultramontanes, still championed “free governments” as confirmed “by the example of Belgium, Ireland, the United States and the republics of [South] America.” One of Daniel O’Connell’s clerical supporters in Ireland, Bishop John MacHale, mischievously offered an after-dinner toast to “the people, the source of all legitimate power.” (Word of the toast reached Rome, and a curial official rebuked an unrepentant MacHale for provoking imperial British authorities.)

One problem faced by these Catholic democrats was increased confessional tension. Protestants watched the ultramontane revival with dismay, and just as Catholics touched by the revival became more intolerant of ecumenical dialogue, so, too, did Protestants. During the 1830s and 1840s, proponents of the “Second Reformation” emerged in England, Germany, the Netherlands, Switzerland, the United States, and Canada. They founded dozens of Protestant associations with such titles as the Evangelical Alliance, the Protestant Association, and the Protestant League and produced histories of the Reformation that painted Luther, Calvin, and other reformers in heroic colors.

Allied with these Protestants were anticlerical nationalists, much like Mazzini, raised in Catholic countries such as Italy, France, and Mexico but wary of ultramontanism. They rolled their eyes at the religiosity of their Protestant allies—German radicals found it preposterous, for example, that Anglo-American Protestants lobbied for the Sunday closure of beer gardens—but found it easy to join forces against the Roman church, what one contemporary named as our “common enemy.”

Both Protestants and anticlerical nationalists stressed Catholicism’s enervating effects. A member of Parliament from Glasgow explained: “In Ulster where Protestantism preponderates, there is wealth, comfort, peace, freedom, knowledge, enlightened and real loyalty. In Connaught, where Popery predominates, there is penury, misery, slavery.” Switzerland became another proof point. One minister crossing the border from Catholic Turin toward Protestant Geneva concluded that “the people who drink the stream of Romanism and live on that side, are lean, poor and ignorant.”

The notion that Catholicism diminished economic progress was reinforced by a conviction that Catholicism generated retrograde views on the family. The increase in the number of women choosing to enter religious orders—consciously rejecting marriage and the patriarchal family—seemed positively dangerous. Protestant and secular reformers across Europe and North America promoted tales of nuns allegedly imprisoned in convents or lured away from their families. In France, an English Protestant father sparked an international debate by alleging that his twenty-one-year-old daughter had been lured under false pretenses into a French convent. Rumors of imprisoned Protestant girls in Boston led to the burning of an Ursuline convent in 1834. The next year Protestants bitterly complained about “a nunnery” with an attached school in Newfoundland and attempts to “ensnare the poor and ignorant into the trap laid for them.”

The most controversial issue in the 1830s was marriage. The problem was simple: how should the state regulate interfaith marriages? In Cologne an aristocratic archbishop, Count Ferdinand August von Spiegel, and the Prussian state negotiated an agreement that Catholic priests could passively “observe” Protestant-Catholic marriages conducted by a Protestant minister. Girls born to Protestant-Catholic marriages would be raised in the faith of the mother and boys in the faith of the father.

This marital détente collapsed in 1837 when a newly appointed ultramontane archbishop with the formidable name of Clemens August von Droste-Vischering angered Prussian officials by insisting that all children of mixed marriages be raised as Catholics. Hardliners in the Roman curia came to his support. Prussian authorities responded by imprisoning Archbishop Droste-Vischering for disturbing the region’s religious peace, and this imprisonment made the ultramontane revival a political as well as a religious event. As one of Daniel O’Connell’s friends explained, the Cologne crisis demonstrated that “if we consider the State of the Church in Switzerland, Russia, Prussia and elsewhere, we will find it suffering more now from persecution than it has for centuries past.”

Advocates on all sides furiously drafted pamphlets, the most famous by Munich’s Joseph Görres. (Görres had arranged for the translation of Joseph de Maistre’s Du Pape into German in the 1820s.) Görres stressed loyalty to the papacy. “I cannot and may not appeal to other than the pope,” he pronounced, the “head of the whole Church.” The idea that Protestant Prussian bureaucrats would dictate how Catholics understood sacramental marriage was intolerable.

These tensions between Protestants and Catholics, or secular nationalists and Catholics, extended to South America and then back again to Europe. Lamennais’s first Spanish translator, Francisco Bilbao, came to public attention for his attacks on the church and its hierarchy in Santiago, Chile. Bilbao assessed Catholicism as in direct opposition to the “human self” and the need for free trade, public education, and representative government. In the early 1840s he made his way to Lima and then Paris, where he again found himself in a maelstrom of anti-Catholic agitation. Eugène Sue had just published a serialized novel, Le Juif Errant, that became one of the century’s best sellers. Despite the title—“The Wandering Jew”—the plot revolved less around Jews than around crafty Jesuits maneuvering a vast fortune away from an honorable but needy French Protestant family. In Colombia, legislators referenced the novel in an ultimately successful campaign to expel the Jesuits. In Belgium, crowds inspired by the novel vandalized Jesuit residences and schools and chanted anti-Jesuit slogans in the streets.

Bilbao chose this moment to enroll in a course on the Jesuits offered by the historians Jules Michelet and Edgar Quinet at the Collège de France. He learned there that Jesuitism and ultramontanism menaced new nation-states. Michelet and Quinet compiled their lectures into another anti-Catholic text, The Jesuits, with global circulation. The choice patriots faced was stark: either “Jesuitism must abolish the spirit of France,” Michelet and Quinet explained, “or France must abolish the spirit of Jesuitism.” After reading Michelet and Quinet, a Colombian statesman wondered if a Jesuit’s “patria” (or homeland) would always be the Society of Jesus, not Colombia, or any single nation-state.

*

On his speaking tours in the 1840s, Daniel O’Connell demanded the repeal of the union between England and Ireland. He continued to see the papacy as the “spiritual authority” and the “centre of unity, the safeguard of the Church.” In contrast to the 1820s, however, when bishops supported O’Connell’s campaign for Catholic emancipation without hesitation, the episcopal response to O’Connell’s repeal campaign was guarded. Some bishops welcomed O’Connell’s efforts; others expressed doubts. The combination of democracy and ultramontanism, so alluring in the 1820s, had lost some of its luster. “It is the first time,” wrote O’Connell, “that the people and any part of the Irish hierarchy were divided.” The English priest (and future cardinal) Nicholas Wiseman was dismayed by O’Connell’s efforts. “I can see no Catholicity,” he complained. “I fear it is thoroughly of this world. Repeal, universal suffrage, democracy etc. I have all along hated them and detested them and do so as yet.”

British government officials asked Gregory XVI to “discourage agitation” in Ireland. (The pope, who admired O’Connell, did nothing of the sort.) The same British officials—working hand in glove with aristocratic English Catholics—weaned some Irish bishops away from O’Connell’s movement by modifying laws forbidding bequests to the church. They arranged increased public funding for the Irish Catholic seminary at Maynooth, which provoked shrieks of protest from newly mobilized Protestant evangelicals in Parliament who accused the government of funding “a Popish Establishment.”

Gregory XVI’s unexpected death in 1846 seemed an opportunity for O’Connell and other democratic reformers, since Gregory XVI’s successor, Giovanni Maria Mastai-Ferreti, or Pius IX, offered a more conciliatory vision of the church’s role. Pius IX began his papacy by authorizing the first legislative assembly for the Papal States and granting amnesty to political prisoners languishing in papal jails. Celebrations around the world, often led by non-Catholics, marked the apparent reconciliation between the papacy and new ideals of freedom. “The Pope’s object,” explained one Irish priest based in Rome to a colleague across the Atlantic, “is to gain the affections of his own subjects by useful reforms, and to re-establish that paternal form of government which is best adapted to the common Father of the faithful.” When Pius IX greeted Belgian visitors, he praised the country’s combination of democracy and Catholicism. “Thanks to liberty, religion flowers in Belgium,” he said, “and it will flower more and more.” Belgian students reportedly decorated their rooms with portraits of the pope next to portraits of George Washington.

Gravely ill, Daniel O’Connell decided to journey to Rome and meet this reform-minded pope. When he reached Paris, Charles Montalembert insisted on paying tribute to his shivering friend, wrapped in a blanket and barely able to leave his chair. “Wherever Catholics begin anew to practice civic virtues,” Montalembert proclaimed, “and devote themselves to the conquest of their legislative rights under God, it is [O’Connell’s] work.” No one had done more “for the political education of Catholic people.”

O’Connell never reached Rome, but his heart did. He died in Genoa in 1847 after requesting that his heart be carried to Rome, where it was displayed in the chapel of the Irish College, and his body returned to Ireland. At a massive two-day ceremony in O’Connell’s honor, encouraged by Pius IX and held at one of Rome’s largest churches just a short walk from St. Peter’s, Fr. Gioacchino Ventura electrified the audience by denying the need to unify “throne and altar.” O’Connell’s life conveyed a different message. He had proven that “religion could only be victorious by the aid of liberty.”

A new era seemed to have dawned.

EDITORIAL NOTE: Excerpted from Catholicism: A Global History from the French Revolution to Pope Francis by John T. McGreevy. Copyright © 2022 by John T. McGreevy. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.