Many are hesitant to accept the orthodox Christian doctrine on which it is possible for someone to abandon God and end up in hell forever. The reason for this resistance is obvious: if God could have a good reason for permitting such a bad thing to happen to anyone, it might appear as if God is not truly loving or even fair to human beings. God is infinitely powerful and knowledgeable, and we are not. In even suggesting that God could have a good reason for allowing anyone to persist in their sins, and find in their sin everlasting unhappiness in separation from him, Christian orthodoxy appears to make God a moral monster who would abandon his children. As some see it, then, “this despicable belief [in hell] is profoundly irrational and propagating it constitutes nothing short of the vilest psychological abuse.”

I acknowledge that the orthodox doctrine of hell generates difficulties of this kind for many people, but I have argued in my last piece that their difficulties result entirely from a conception of hell which is not that of the Church. God is not one who abandons his children, even when they choose—not because of anything God either did or failed to do—to reject his love. I, therefore, reject the moniker “eternal conscious torment” for the traditional doctrine, as God does nothing to torment anyone. This was my response to the way in which God might have good reasons for allowing hell: if God allowed hell, hell could be nothing other than an expression of God’s mercy and love even for the damned.

God allowing someone to reject him would be part of God’s gracious plan to triumph over all evil—that felix culpa which stands at the heart of the Christian mystery of salvation is one that God only allowed because he had preordained a remedy in sending his Son to die for our sins. Without that possibility of eternal spiritual death, the triumph of the Cross would not be (as we sing in my Byzantine tradition) a victory “by death trampling death, and to those in the tombs granting life!” The Cross would be a victory over suffering, pain, or ignorance, but would not be granting life to those who otherwise would have lived in eternal separation from his love. My point is, then, not that we have to believe hell is occupied, but that the teaching on hell is part of the Gospel message—without which our rejoicing at Easter does not make sense.

All of this sounds nevertheless shallow and pitiful to those who cannot imagine any such reason. I have begun with the belief that God is all-good, all-knowing, and all-powerful, and conclude that, if God permits hell, he would not do anything to cause people to go there but would only allow it for a very good reason compatible with those properties of being all-good and so on. Many run the reasoning in the other direction, because they see no possible point in God allowing anyone to persist in rejecting his love and remain in suffering forever: if he were to allow hell, then, God would not exist, or be all-good, all-knowing, or all-powerful.

Those who embrace the orthodox doctrine of hell, like myself, must be merely deluding themselves (they think) that we would be safe from hellfire, or do not care deeply enough about their loved ones and friends who might end up there. That is, if God did permit hell, the world would be a terrifying place, and no excuses about God’s plan or greater goods or the Cross or our free choice would be enough to assuage that fear. Or, at least, the world would be irredeemably tragic and hopeless.

Christian Hope

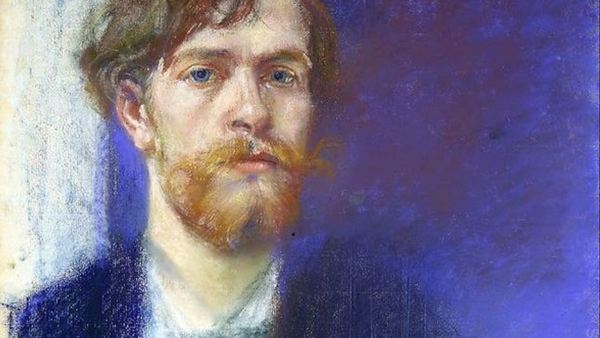

St. Francis de Sales as a young man experienced a spiritual crisis. After hearing a university lecturer expounding a Calvinistic, determinist theory of predestination, Francis became unsure whether God too would abandon him to hellfire, which naturally caused a great interior struggle. But he did not give up praying for help. Francis eventually went to a church run by my Dominican brothers, where he prayed:

Whatever happens, Lord, you who hold all things in your hand and whose ways are justice and truth; whatever you have ordained for me . . . you who are ever a just judge and a merciful Father, I will love you Lord . . . I will love you here, O my God, and I will always hope in your mercy and will always repeat your praise . . . O Lord Jesus you will always be my hope and my salvation in the land of the living (I Proc. Canon., Vol. I, art. 4).

It was at this moment his fear left him, to be replaced by hope.

Francis’s problem of his own predestination is the same issue, writ large, as that of whether God will save all human beings from everlasting separation from him. And Francis, like us, does not end up with the knowledge that God must save all people, he does not end up with the knowledge that Francis cannot end up rejecting God or that God cannot do otherwise than save Francis. Instead, Francis’s fear leaves him because, even if Francis cannot imagine what God will do, or how God will do it, Francis comes to trust God. In that trust, he knows that nothing God will ever let happen to him will be ultimately tragic or hopeless.

Hope is nevertheless easily confused at first glance with being convinced or confident that something is true, i.e., a kind of credence or “epistemic confidence.” Instead, hope—just like the virtue of faith!—is trust of God. Hope is neither merely high confidence that God will do good things for me nor certain knowledge that God cannot do anything other than save me. Hope has as its object a person, for their own sake, and not for the sake of what they will do; just as faith is a virtue of trusting what God tells us, but because he told us, not because we have independent evidence or knowledge that what he told us is true. To be hopeless, then, is to fail to have a kind of trust in God that he will do good for me or for those I care about.

But being hopeless can express itself in two distinct reactions. One of these is obviously despair. To despair of God’s love, as we know, is deeply irrational. But despair is not irrational merely because it fails to be aware of the evidence that God is good and will love us, or any other evidence or knowledge at all.

Despair

Put ourselves back in that situation recounted in my last article, standing next to your beloved. They are not looking toward Mount Zion, but into the abyss, contemplating jumping in and trying to remove themselves from the company of the blessed in paradise. You ask them, “What are you doing? Don’t you want to be with us?” They respond: “There is nothing for me there. Nothing in this world for people like me.” This person does not need an argument or evidence to convince them that they matter. No matter how many syllogisms you give them, they will be totally unmoved.

It is not time for syllogisms or convincing, but to help them by being with them. This is often the only way we can break people out of their self-imposed delusions about their worthlessness and hopelessness (by action) since it is the one thing that might break through all the rational barriers and excuses and bad habits that someone in despair builds around their own hearts. Trying to hold on to their hand is good for that person who despairs, we know, even if it never convinces them to change their mind.

To be hopeless, though, is not just something possible for the person wanting to commit suicide. Letting go of our beloved’s hand “for their own good” would be equally an expression of despair, in my story. To let go of their hand is to accept, by our action, that their life has no meaning and does not matter. The despairing person who thinks that they do not deserve to be at the Banquet of the Lamb, just as the person who thinks that someone’s life would be better if I were to help them end that life by suicide, is wrong.

Despair is not irrational as if the despairing lack reasons. There is no lack of arguments or reasons that people in these positions can give to justify their views that their own life, or that of another, would be better if it were ended. The phenomena in our world of assisted suicide express this deeply irrational and evil attitude toward those who feel worthless or in pain or in difficulty and want to end their lives as a result. Despair often can be thought to consist of a lack of care, even hatred, for ourselves and others. Yet, advocates of this state-sponsored suicide seem outwardly like rational people who care about giving disabled persons or those with painful illnesses a “dignified death.” Despair is not essentially contrary to love but to trust. That is, looked at more accurately, despair relies on an irrational love of self that is incompatible with trusting others.

What goes wrong is that despairing people do not pay attention to, do not trust, other people around them. They do not see that others want their good and that their life would be better if they would only turn their eyes and acknowledge their need for help. They do not see that there is help available. The advocate of assisted suicide too does not pay attention to the way in which human lives are social, and that our lives can be worth living—even amid terrible illness and disability—when we have friends who can help us. Our moral duty is then not to end the lives of the lonely, the severely disabled, or the mentally ill, but to do all in our power to make those lives livable again. As Mother Theresa put it, “a person who is shut out, who feels unwanted, unloved, terrified, the person who has been thrown out of society—that spiritual poverty is much harder to overcome.” The Christian then has hope, as she did, that help exists in the form of those who can make a difference and help us get through our suffering. Those friends who care for us are all around, even when we cannot see them.

Presumption

There is yet another way to be hopeless. In the controversies of the Protestant Reformation, the Church condemned those views held by some Reformers on which faith required an absolute certainty in one’s own salvation and predestination.

No one . . . so long as he lives this mortal life, ought in regard to the sacred mystery of divine predestination, so far presume as to state with absolute certainty that he is among the number of the predestined, as if it were true that the one justified either cannot sin any more, or, if he does sin, that he ought to promise himself an assured repentance. For except by special revelation, it cannot be known whom God has chosen to Himself (Council of Trent, Decree Concerning Justification, ch. XII).

The Church was not insisting that everyone should live in pathological terror at the prospect that they might not be among the predestined and so end up in hell (as polemical objections sometimes misrepresent the doctrine). Those with absolute confidence are also hopeless, but for a different reason than those who despair. A complete certainty removes the need for trust and lends itself, as it did practically among Calvinists, to working out a deterministic picture of the universe without any possibility of human resistance to God’s grace. Trust, by contrast, is not mutually exclusive with the fact that I need to work with God to make my election secure (2 Peter 1:10–11) and so work out my own salvation with a healthy fear of my own weaknesses (Phil 2:12). In trust, I know that I might possibly resist God’s grace, but I know that God is also Good and that He cares for me—Christ, then, is my fortress and bulwark against myself.

Hell being a real possibility is not God’s doing but mine. What we inflict on ourselves and each other: a world of eternal death and sin that would be the case for eternity if he had not died on the Cross. God therefore became man in order to save us from the consequences of our own actions, a life of sin and death that we would live without him. Rejoicing in the Cross makes little sense if there were nothing to be liberated from. If it were not possible for us to end up in eternal death, if Christ did not harrow hell, Easter is a sham victory, “our preaching is empty and your faith is also empty” (1 Cor 15:14).

Paradoxically, the Catholic position on certainty of predestination aims to rule out absolute confidence precisely so as to preserve our trust in Christ and his Cross. To say we do not need to trust God implies that we do not need to trust God to have his help. “Presumption” is that attitude on which one acts as if trust of God is unnecessary for my own good. The despairing fails to trust because they think are focused away from those around them, oftentimes because of fear and sadness, sometimes (as with mental illness) even being so strong as to impair their thinking. The opposite situation of presumption is much more serious because, without any such mitigating factors, a person misidentifies what is good about trusting God.

Why You Cannot Win an Argument with Hard Universalists

Discussing and arguing with hard universalists is intensely boring, as conversations around this topic take a predictable form in every instance and very few new arguments are ever given. Universalists claim we can know God must save all and propose various arguments that deny either that God could do anything other than save all (he had no possible good reason to permit hell to exist) or human beings cannot persist in separation forever (mortal sin is metaphysically impossible). One points out that these arguments lead to contradiction with the Church’s teaching or Scripture on any number of points, prompting universalists into a flurry of ad hoc rationalizations before ultimately rejecting all adherence to authorities that might contradict their own presuppositions. One prominent universalist summarized their view nicely: “If the Church and Scripture teach it, so much worse for them. If that is the case, I want nothing to do with either. If authentic Christianity teaches eternal damnation, I want nothing to do with it.”

Problems of evil—such as the problem as to whether an all-good God can permit hell—argue that a certain instance of evil is incompatible with God’s goodness and conclude: “therefore, God does not exist” (or is not loving, etc.). But these arguments are logically unsound and invalid for the reason that an all-good, all-knowing, all-powerful God can have some good, justifying reason for allowing any given instance of evil. I might not know what it is, but, if some such reason is possible, there is simply no logical contradiction between God’s existence and any given evil, including the possibility that God permits us to reject his love forever.

Universalists respond to such points on a discussion-ending note: they assert that anyone who thinks that God could have some such reason (one we cannot imagine) is morally broken, never having loved or been loved, etc. And David Bentley Hart goes the full mile: if even God himself had such a reason to permit hell, God would be a “sadistic monster” (That All Shall Be Saved, 192). Thus, infrequently is someone convinced by argument or authoritative evidence of any kind against universalism, whether the Church or anyone else. The problems that lead people into belief that God must save all lie outside of logic and evidence. It has to do with hopelessness.

From my perspective, we can always be more confident, as Christians, that God is good than of any evidence in favor of any instance of evil we see or experience being pointless or meaningless. So, if evil occurs, we can be confident that God has good reasons for permitting it. This point is not very strange or controversial, I think, as it formalizes the “hopeful” reasoning by which Christians respond to evils in their life:

1. This bad thing that happened to me or my loved ones seems to me as if it is pointless and meaningless.

2. But, I know God is good and is perfectly in control of the universe and wishes nobody any harm.

3. So, I know that whatever happens, even bad things, are only allowed by God because he has eminently good reasons for allowing them.

4. Therefore, I know that this bad thing that happened to me or my loved ones is neither pointless, nor meaningless, but something allowed by God for our good.

If we were to discover that God made it possible for us to resist his grace forever, then, I would think, we come to know that, if he did so, he did this for a good reason that was an expression of his love and mercy for us. I would be more confident of that than of any argument to the contrary, even if I were unable to imagine any possible reason that God had for doing so, because I think it is good to trust God.

As a heresy, hard universalism necessarily involves and gives birth to spiritual errors that affect our Christian life of hope. Hard universalism, in a profound way, misses the point of Christianity. It misses, as I have already argued, the point of the Cross and what we are saved from. But, if universalist arguments that supposedly give us “knowledge” that God will save everyone were true, this would also make trusting God unnecessary. “For we were saved in this hope, but hope that is seen is not hope; for why does one still hope for what he sees?” (Rom 8:24). Knowledge that God will save all, on views like “hard universalism,” is just supposed to be knowledge that things could not have been otherwise. If things could not have been otherwise, then either I or God are unable to do otherwise, trust would not be a central Christian virtue, intimately related to our salvation. Our salvation happens without any intimate relation to faith, hope, or love.

The Advent

We should, therefore, first, reject any claim that we need to know God’s reason to permit anyone to reject him. I do not need to know or be able to prove that everyone is going to heaven in order to trust that God loves me, will not abandon me, or that he will take care of my loved ones. I do not need to know whether hell is empty to know that Christ comes to harrow the hell in my heart, a hell that would be my eternity if I were not to cling to him.

But we should also reject the claim that this attitude of trusting God, even in the face of an evil that looks irredeemable, is irrational. Whatever happens in the end, whether or not there is anyone in hell, I would have no reason of any kind to fear that God will abandon those who are there or to think that this world is tragic, irredeemable, or hopeless. I will know when I see him face-to-face why he permitted us to shut our hearts to his, but, in the meantime, I know with certainty that God is the Good, and that gives me reason to hope. For “hope does not disappoint” (Rom 5:5) and that is what makes hope rational.

Discussing whether or not hell is empty is consequently a fruitless and pointless discussion, as what makes hard universalism heretical is not merely that it is a false belief about how many people there are in hell. Instead, hard universalism claims a world in which things could not have been otherwise, in which all are saved necessarily, is the only world that matters, and that—if things could have been otherwise—then that sort of world where rejecting God’s love would be possible would be at least irredeemably tragic, if not terrifying. But, for Christians, a world where there is an all-good God is necessarily one that is full of hope and possibility, no matter what happens.

In the same breath as condemning the certainty of epistemic confidence, the Church at Trent pointed to trust: “let no one promise himself herein something as certain with an absolute certainty, though all ought to place and repose the firmest hope in God's help” (ch. XIII). Leaving behind universalism’s attitude of presumption leaves us not with terror, but with hope. As 1 John 4:18 says, “perfect love casts out fear.” John’s explanation is that love does so “because fear involves torment. But he who fears has not been made perfect in love.” There is of course a kind of healthy and unhealthy fear. Hope begets in us a filial fear, a healthy awareness that I need help to live a good Christian life. We cannot understand hope without being aware that my life could be otherwise, and that fear of punishment—pathological fear of sin, death, or God’s abandonment—is that from which Christ came to liberate us. The hope we have in that God is what allows us to trust that the story of God’s love for us can extend to hell, and that no matter if anyone is there (or not!) God’s goodness will be all-in-all.

Hopelessness, by contrast, inevitably results in disappointment. Both despair and presumption involve placing our trust, and the ultimate good of our life, in something other than God himself. God desires nothing from us but our hearts. His reasons for allowing what happens in this life, including even his permission of our sin, is only to bring us into that union with his Sacred Heart. Christ’s words that “at an hour you do not expect, the Son of Man will come” (Matt 24:44) aim not to inspire terror but trust in himself, the Son of Man, because our reward is nothing other than him.

The attitude of trust that is found in hope and faith cannot exist in a heart that judges divine things by its own standards, that puts its love in something else above love of God, because reality might not correspond to the way that we expect. If things could have been otherwise, and we come to discover too late that our trust in God’s goodness would have changed the way we see the world, then our expectations about God will inevitably be dashed upon the rocks of reality.

If we were terrified of God, under the belief that he has set up the world for us to inevitably fail and that we could not have done otherwise than remain caught up in our own sorrows or fears, or, if we come to build all of our hopes and dreams upon the belief that our life choices or those of God could not have been otherwise, and would hate a God who would have let those choices be otherwise than we imagine possible, then I could think of little greater torment, disappointment, and dashing of expectations for someone of that persuasion than to become intimately and profoundly aware of nothing beyond that God’s glory for eternity.

But those who have faith and hope know that God is all that really matters—our supreme Good—so that God drawing close to anyone can only be for their own good, whether God will meet their expectations or not. When we have hope, we already expect that God’s goodness will shatter even the limits of our imagination, and that, even when things appear to be hopeless, they never are.