Something always happens—an image, a moment, a terror, present one second, escaped the next—and we find ourselves thrust upon the sword of our own creeping mortality. This moment of sharpened clarity occurred to me one evening as my father’s legs gave out. They buckled underneath in rapt unison, balletic and violent against himself and his being. His spirit submitted to the law of gravity, his lifeforce was willed to the material floor by an unseen power too close and too universal to differentiate from the scenery. The heavy materiality which refused to act as his body further refused the soul, once its great friend, its walking stick and guide.

I gasped at its presence, at its handsiness, which dressed me down and revealed my unpreparedness for the eternal things, for the little things, for the dappled things. We had been prepared that my father is declining and nearing more active death. Everything prepared us: the hospitalizations, the body wasting, the breathlessness, dementia, fear, fear of night, of hospital beds and long antiseptic corridors of loneliness, and of wild ancient memories cut with fine teeth of ennui and recollected childhood, some real, some fantastic, mixed with failed loves, regret, and the heart-aching need to square the circle, to achieve the harmony within the family intimacies which, with that long day’s journey into night, had perennially and rudely escaped such things, and would likely do so after his death.

My father’s head fell back like an infant whose neck had not the strength to support its own head, of another pieta now softened into flesh. His eyes, which for days moved back and forth across the room speaking for him in his muteness, had rolled up into his head producing in me such inadequacy and the unreadiness to relinquish him. Then, the exacting, ever exacting and vitiating moment where death made its presence ferociously known was through his mouth. It had arrived, his mouth opened as if to gasp, wider though weaker in appearance. A dull cavernous space half-mouthing in silence. Everything, all sums, the geometry of expectation settled into a more secret number, everything I am in littleness, both in presence and absence, dilated and restricted. As if a sky that had never been punctuated with the lights of civilization had recovered within his mouth its dark pitch and stars. All things that I was, and ever will be were placed within, the sum total of what eludes capture pulled me with him to my knees onto the floor. Do I even know what is meant by “only say the Word . . .”?

There I was, without knowledge or wisdom, looking for the unsaid word on his lips, the word which could undo this sentence surely and irremediably placed upon all my line, on every family line, and every living thing, on my husband, on my dear little ones. To know and not know all the same, this is what death does to us. This sentence is on my children, full of life and promise, born with imagined endless possibilities, bathed in heated waves of anticipation, hope, and futurity, born with gleaming sunbeams in every crevice of their soft faces, and still the secret passenger has found its way into them before they were born. The pain of birth, its torn separation, has from the outset already pronounced its final sentence. My father was once this child, an unrepeatable moment of wave upon wave, and light upon light, he was once a little dreaming face calling forth seas as deep as memory, calling forth infinite promise upon promise. My father, slack jaw and almost past knowing and being. We wait for death. “Weave a circle round him thrice, and close your eyes with holy dread.”

The Loss of Heaven as Loss of Faith

The loss of a real and heartfelt belief in God—and by “real” I mean an experience that is both steady and moving, ethereal though down-to-earth, sentimental but never trite—comes from an earlier more foundational loss, namely that of an ardent and directed desire for Heaven, and more specifically, that paradisal longing for the Resurrected life. Have we lost what it means to desire the afterlife? The nature of Heaven itself may play a part: mystery left unnurtured even degrades into something “out there” and unknown, degraded further into a vague wish for immortality, and finally into the blank and empty words of consolation. Or even worse, the almost comic book reduction of Heaven to an earthly utopian Paradise, the immanentization of the Christian eschaton.[1] The “better place,” which means well, often means nothing at all, or, worse than that, becomes the very foil when approaching the mystery of grief, and the possibility of a meaningful and spiritually fruitful conversion through it. The implicit sense of Heaven within those words may itself actually be further obscured; the afterlife is only thought of from within the fear and folly of death, and serves only to distance us from the anxiety and homelessness which occurs in the living after the loved one fades from view. Somehow, we simultaneously remember and neglect the words of St. Paul: “For this world is not our permanent home; we are looking forward to a home yet to come.”[2] And this neglect is a different type of forgetting than the briefly misplaced book, only to be rediscovered in the armchair, just as intact as it was before. The Heaven that is our home is not as easily rediscovered, nor are we as easily recovered intact,[3] and death becomes yet another social inconvenience.[4]

Death and Grief: Unexpiated Tears

The rules that death lays out on the table evoke an unrepeatable experience that communicates through stasis and movement; and wherever you are, death is at the opposite end of the pendulum. Should one in grief enter into the stillness preceding and inhabiting memory, death reminds us of movement—the sun rises, the tides change, life goes on, and if one embarks again on these motions of life, death reaffirms such a stasis that returns us to the coalface and to the unexpiated need for what is lost to be found and to be loved as it was, once again. Nothing is as it seems, and nothing is recovered. In the grief which separates the living from the dead, the living are compelled to life in a realm where worlds—which by logic and good reason—should never collide and inhabit the same person; but they do just that, cultivating a new avenue of experience. And it is never quite so simple to say that this is, this finally is, the road home.

Part of grief’s virulent stubbornness is because our faith is too weak to envision Heaven, and thus too weak to sustain genuine hope in the afterlife. We think, believe, feel, viscerally experience, that we have lost it all in the death of the other—and part of this kind of grief does come from an infirmed understanding of the “better place.” But we also grieve with such awful humbling violence because we have been torn from the union that gives us a foretaste of Heaven. We are the body of the Church and Christ is its head, and through the Head the body has possessed in the flesh Heaven.

In the grief that places us within the incommunicability of death, the only way the mind functions is to be memorial. Catholic teaching is a paradox undergirded by conflicting layers of nature. Even when we look at the many things that bring us joy—the joy as signatory of Heaven—whether it be laughter, intimacy, or childhood, we find that these things are dependent upon a human nature built in layers of conflicting fabric. Each of us is:

- a yearning remembrance for a pre-fall state we cannot quite recall, let alone recover. We glimpse it in childlike innocence and yet long for this strange, un-known, un-grasped state with a stubborn and persistent wantonness, which itself becomes either the terrible hubris within all human goals and motivations, the resignation to the meaningless labor of Sisyphus, or the holy eros, which leads to the sheer agapetic sublimation necessary for faith. Each of us is:

- in a fallen state that struggles to make good out of evil, so that the things we cherish have their goodness spread, indeed woefully diluted, among natures and conditions that must be transformed to a state of perfection and, to our fearful minds, may not survive such a vast transformation. Each of us is:

- a participant in the flesh and blood of Christ within the twofold reality of Resurrection as hope-filled promise and certitude as trust. This mystery unites the theological certitude of Faith as grace with Love as the offer of the highest, truest, most beautiful union of lover and beloved, and hope as kenotic, utterly emptying itself, denoting “a movement or a stretching forth of the appetite towards an arduous good.”[5] The Christian is both certain and in total longing, in the presence of Christ, who has already run to us, and running towards him all the same.

And the paradox of it all is that in order for us to long genuinely and fiercely for these transformations, we must recover how they are not vitiated or lessened presences, while at the same time we must systematically let go of every earthly love up until the moment of death. The recovery of Paradise in our hearts is a strange and potentially unforgiving affair, but perhaps the most meaningful act of our lives, for through it we can understand the meaning behind the first commandment: “love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind.”[6] Somehow, we must simultaneously experience a letting-go, a type of holy forgetfulness that transgresses and reshapes all things, while hoping for union and reunion with our loves not in a vague form of all-ness, but in a dramatic uniqueness particular to the drama of each human person. How is that possible? And how is it to be lived out? Both unobtainable and necessary, we must find ourselves inhabiting an impossible yet essential harmony: we must be transported to the best of what life is in all its beauty, exotic and familial, but from within the very pulse of a non-annihilating sense of relinquishing everything that we are, with rapt exactingness and relentless precision. We must understand with joy that to relinquish, and to be relinquished, is bliss itself while that very bliss is perfumed with the transcendent incarnation of all of Earth’s beautiful things.

Herein lies the predicament of the Christian philosopher as situated within what has always been the future of Christian thinking: we should never suppose that what death adds to the table is simply removed, salvation is no mere existential fiat. Heaven as eternal life may also be eternal dying; a fulfilled eros of ecstatic surrender. “For in self-giving, if anywhere, we touch a rhythm not only of all creation but of all being. For the Eternal Word also gives Himself in sacrifice; and that not only on Calvary. For when Christ was crucified he ‘did that in the wild weather of His outlying provinces which he had done at home in glory and gladness.’”[7]

Each of us is already inside the twofold nature of death as simultaneously the experience of unrecovered loss, and the confirmation of our immortality, and neither experience expels the other. And this odd, often unforgiving experience, will be with us for the rest of our lives. It is the lover in total self-abnegation to the beloved. It is the death sentence releasing us from death! It is loss as loss, while being gain, and neither does the loss outwit the gain, nor the gain undercut the loss on this side of eternity.

Heaven is the summit and joy of human existence and, at the same time, strangely neglected. We understand it to be the estuary of the Good in which we shall have no other desire than to remain there eternally;[8] that while unseen at present, it is, in fact, the only reality truly experienced as is;[9] that Paradise is the precious crown and treasure;[10] and that either we suffer here in this world through our ardent yearning for God, or suffer in the next through our obstinate denial of Him.[11] Yet still, in all of this, Heaven escapes us. And by this, I mean that the very texture, the filling, the tender incarnality of the place or state or realm or habitation eludes capture with a pervasive and abrupt persistence. And because we are unable to focus our lens to get a substantial glance, we are historically tempted to focus our belief on those so-called “more important” things which are important to the faith but only within the context of Salvation, and Salvation is homecoming, and homecoming is Heaven. All roads lead to Heaven, from the exitus to the reditus. And it is the little things, the specifics, the minutiae that have always characterized a human life embodied by finitude and the longer way [12] of flesh and blood. Thus, the longer way of embodied human life cannot be bypassed in the architecture of Heaven because Heaven is realized in Christ. In unity with Christ, our flesh and blood are incarnated beyond transitoriness, and shot through with a durational eternity. The radicality of such kenosis is stunning: because Christ is God and Flesh, Heaven itself is transcendentally incarnated. Wounded as it may be, our own flesh still has the signatories, the entelechy, to give us a glimpse into Heaven’s fitting abode.[13] This kenosis is, again, innumerably wondrous: when Christ realizes Heaven for human beings, he does so by merging—and without the annihilation of their dramatic differences as such—the presence of Heaven on Earth and even, and more secretly, the presence of Earth in Heaven. In Heaven resides the taste, the hunger for the earthy, the carnal, the dust and the clay, transfixed and transposed.

This twofold union of Heaven’s foretaste on Earth, and Earth’s carnality permeating Heaven, impresses upon us the distinctive anti-fantasist, fully substantialized drama of our human natures always stretching and inclining towards Heaven. The desire for Heaven is not a peripheral yearning, an accoutrement to life’s goals, a wish-fulfilling sentiment soon left at the wayside from childhood to maturity; instead, it is what finally unveils and completes our open human nature. More still, as the Father is only Father in relation to the Son, and the Son is only Son in relation to the Father, then the Father, like the Son, has given Himself need. That need is for their Home to be our Home, that God is only Home because we, in our flesh and blood realized in Christ, audaciously co-substantiate Heaven undergirded by God’s sheer eternalizing presence—this is the true “happily ever after.”[14] Christ has given to human beings far more than we deserve: “we are not worthy for You to enter under our roof, but only say the Word.” The Word has been Incarnated and the roof is formed in this unity of spiritual eternity and bodily duration. What Christ has given us is Himself and thus a co-substantiating power within the very architecture of Paradise!

When the afterlife is no longer strained to be imagined, fleshed out in our longings, envisioned as a dramatic commingling of philia, eros and agape, its architecture recedes only to the depository of thoughtlessness, the unthought festivity that secretly begins the turn away from God more primordially than any atheistic philosophical system. All atheisms begin in a misunderstood human nature, and that error of all errors originates in the loss of Heaven, for our human nature is realized only in our permanent home.

Perhaps the hesitancy we face when attempting to dwell on Heaven is rooted in the crisis of the separated soul, which conjures an anti-phenomenological state uncomfortably closer to non-being than to the concrete life of carnal existence. If we take the dry Thomistic language that the soul is the form of the body and realize it in its luminous radicality, not only is the body for the benefit of the soul, but the soul also achieves its perfection and raison d’etre in the body. If the soul is the form of the body, how can it be claimed that we do not lack and long in Heaven and yet how can we lack, and audaciously claim such a possibility, now wholly united with God?[15] The state of the separated soul is, indeed, the crisis that hits at the very core of our unrepeatability as persons within the dignity of human nature.

Our recoil at the emptiness of a disembodied state-of-relation “better place” is more than understandable, it is true to form and to embodied being. This must not be forgotten. To ignore the unease, the sense that something does not compute within this mystery, is to deform the promise of Paradise into unreasonable unknowability, and to a sense of embodiment incapable of genuine eros and agape, and to a faith so regrettably unworthy of belief.

Incarnated Intentionality as Crucial Signatory of the Afterlife

We seek to clarify the importance of our integral humanity when unpacking the conceptual and existential difficulties in justly raising Heaven above a phenomenal vacuity. It is critical that we recognize the unbroken thread in all human experience: any act of thought, engagement, or experience places us simultaneously inward—through and beyond ourselves into our originary filiation with the uncreated as mystery at root in all things—and outward—into the other as other of our shared world of incarnality. It is never one or the other, all human experiences place us within this dynamic analogical intentionality that stretches human persons beyond themselves in order to be themselves.[16] No human person is a static entity, a closed essence; the union of body and rational soul, flesh and spiritual tending, allows us to experience, to be experienced, and to experience being experienced.[17] To think is to think of things, to be a being of and in the midst of presences, persons, places, relations. This interiorization of the other, which includes the form of self that the other has previously exteriorized, and the exteriorization of the self, which includes a form of the other previously interiorized, evokes the very essence of conversation.[18] This inward and outward process of becoming the other as other is grounded on our participation in God’s uncreated To Be, which is epiphanically experienced in us as moving and incarnated images of eternity.[19] This is the intentional or tending structure inherent in all human acts[20] and only by grasping this thread can we encounter what eludes us in death, and understand why the “better place” terribly undercuts the magnificent fulfillment of intentionality in Heaven, more magnified in the Resurrected State.

We are all responsible for others because each of us is a result of responding to others in such a way that our very temporality is altered, i.e., how we see ourselves in the past, in shifting memories, in the anticipated future, and our power to cultivate said future or not. This primordial intentionality is not something we are able to choose or refuse; it naturally/intrinsically occurs by virtue of being ourselves in action. Recognizing this community of beings changes the understanding of what constitutes personhood. Our thought processes are not a compilation of vaguely phenomenal egos, somehow independent and distinct. Instead, what we call “our own thoughts” are always manifestly tied and bonded to others/otherness as inward towards the un-created and outward amidst finite beings. This tending is a spiritual and familial scaffolding (oikos), we graft the very architecture of the world, foreshadowing the hope that, through Christ, we co-substantiate the architecture of Paradise, befitting the shared unrepeatability of our human natures. Only when we recognize that sheer primal interconnectedness of intentionality can we approach human flesh[21] as signatory of Christ’s Flesh. Only when we experience that which lays at the center of our own soul and has always laid in the center of another, can we glimpse how Christ’s Incarnation brought a glimpse of Heaven to Earth through love and responsibility. The human soul here is not something poured into the body, but an analogical unity of tending flesh. This incarnational intentionality, where we become the other as other, involves every avenue of human comportment. It is:

- a metaphysical phenomenology as the simultaneous two-fold tending towards otherness, inwardly in filiation with the uncreated To Be, and exteriorly within the netting of finite beings; this is the first scaffold of our being-in-the-world. It is:

- an epistemological ethics as a lifetime’s interiorization of the other, which includes the form of self the other has, repeatedly in varying degrees, previously exteriorized. And the exteriorization of the self, which includes a form of the other has, repeatedly in varying degrees, previously interiorized.[22] This is the daily scaffold of being-in-the-world. It is:

- a theological mystique as co-substantiating the ethical, spiritual, moral, aesthetic architecture of the world as foreshadowing the gift of co-substantiating, through union with Christ’s flesh, the architecture of Heaven. This is the intentional fulfillment of our being-in-the-world.

How can we complete becoming the other as other, how can we know ourselves, if death is the torn separation of the human person, the rupture of the human essence? Christ’s flesh completes what ours could not, it completes the intentionality where ours stalls again and again, experienced in grief over the death of the other: “ring out the grief that saps the mind for those that here we see no more.”[23] Christ not only completes in us what we have failed to complete, but gifts us with co-substantiating his wounds, which are the architecture of the Church and family, the glimpses of Heaven on Earth, and through them we traverse the celestial architecture to come.

Christ’s Infixion: Speculations Regarding Embodiment and the Senses in the Resurrected State

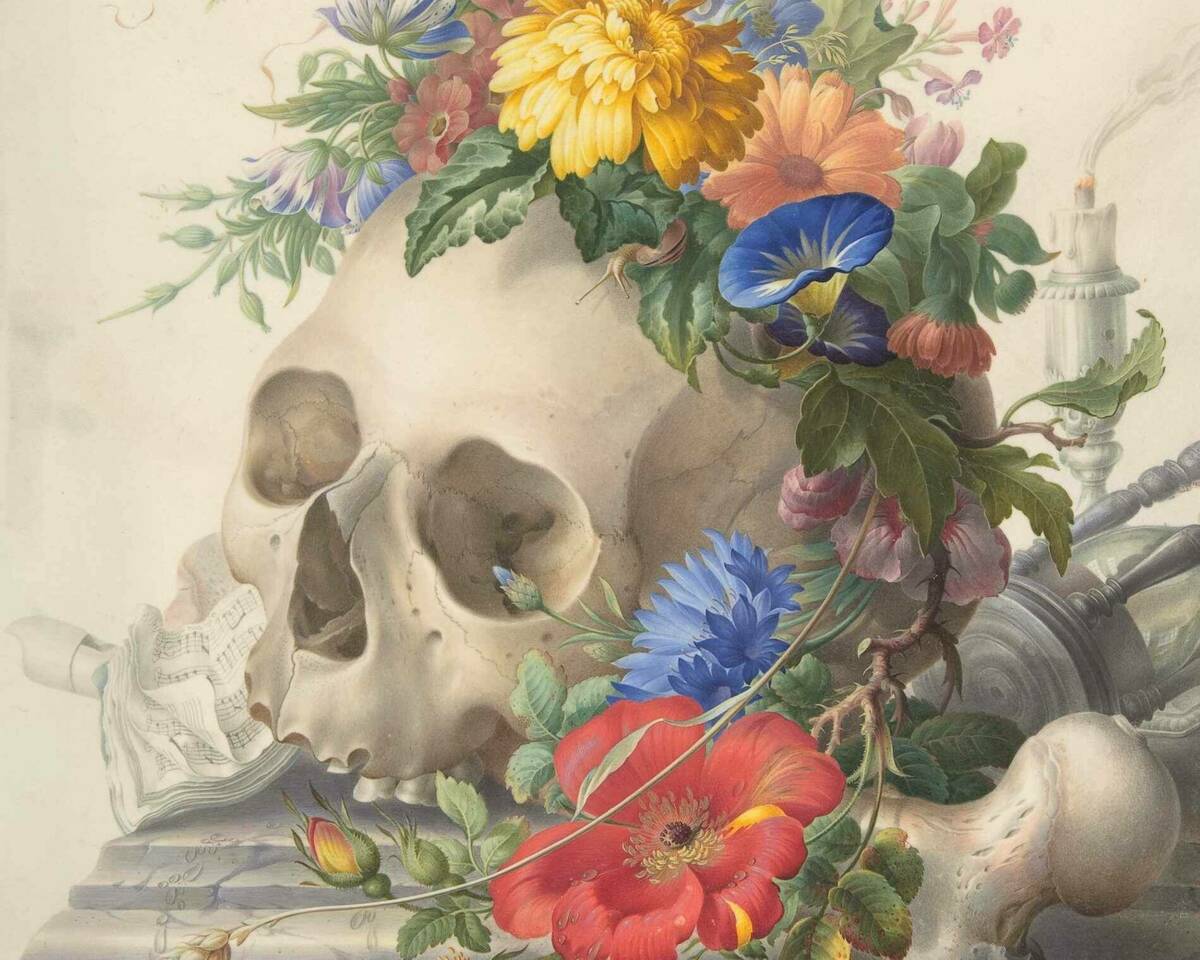

Christ has created through his death the new realm of possibility by which we act out our incarnated immortality. We must take a closer look at how the senses are in relationship to death if we are to glimpse a vision of our Resurrected State. Christ resurrects with his scars, this signifies that death paradoxically dilates our understanding of the glorified body. Here we encounter the Platonic paradox never to love our lives so much that we render them unworthy of living.[24] The best of who and what we are is discoverable in the protracted, underlying, encompassing, sanctified dying within daily living. It is the look and touch and aspect of this dying that is not ignored but transformed in the Resurrected State when Christ overcomes the world. Death is not to be viewed through the lens of morbid and obsessive fear or obsequious reverence. Instead, the strong, vital desire to engage life most vigorously and within the Beautiful always means a natural, almost unthought, but dwelt-in, readiness to die. Such a person is nourished on the nectar of ecstatic Being, has drunk deeply from the wells of eros and agape, whose love of the dappled things radiates from his breathing and gestures. This person is capable of such magnanimous beauty because ge is a friend to death because his existence is markedly kenotic.

Our glorified bodies dramatically unveil Christ at our left, and at our right, above us, below us, in the midst of us, inside of us,[25] radically fulfilling our co-substantiation of Paradise. The armor of God that we place upon ourselves in life is not a struggle against flesh and blood,[26] but against the evils that degrade its magnificence to carry eternity in time. More still, this armor is nothing other than flesh itself, Christ’s flesh and blood infixed upon us. Christ’s Crucifixion is also an infixion: a yielding of the flesh to the Word being placed, inlaid, infused within it. The nails and lance which scar him pour forth his vital essence and fill the Word within us. This infixion fills our scars, the lines on our faces, the cracked hands, all the signs of death, disease, decay, old age, which simultaneously evoke our personhood and our failure to transmit and communicate what lays most truly within us. The God-Man’s kenosis overflows into his infixion: Heaven as Christ’s Body is now ours, suffused with his in the Resurrected State.

The kenosis signifies the defragmentation of our senses, the power that enables each one to signify the whole. To see Christ is to taste him, to hear the lover is to embrace him. The infixion confirms that this unity of the senses in the glorified state is not some power of supererogation placed atop our senses, not a superhuman superpower indifferent to our earthly senses or outside of our life experiences, but won through them, achieved through their weakness, filling their dying, transfiguring their failing actus. Christ condescends to become united with my eyes, my hands, my lips and tongue: this is the greatness of his infixion. Because every glorified body is infixed with Christ’s kenotic presence, our senses in Paradise would cross every divide. In our glorified bodies we now forever touch Christ’s garments, and through this permanency all has been made well. In the Resurrected State, our senses are penetrative, each evoking the other, fulfilling immediacy. The touch of another’s arm or face enables one to love the other with such intimacy, as old friends, because the unveiling of shared experience within the touch is not as isolated ideas, facts, or descriptions of past events, but as a total unitive experience of incarnational intentionality where all things are made one and overwhelmed with goodness and sanctity.[27] The hearing of praise in Paradise would elicit the taste of nectar. Forgiveness would take on the scent of every sweetness, bread pulled apart, the freshness of ocean and tide, domestic and exotic, known and unknown. Our senses in Paradise fulfill what is sensed on Earth when we embrace, when we kiss, when we seek furiously to touch something more than skin deep, when we inhale the garment of the lover now dead and seek to reclaim with our very smell and breathing the life of the other. The bride will grasp her Bridegroom and not let go.[28]

What becomes of Sexual Intimacy in the Resurrected State?

With such a vigorous sense of fellowships, unions, and friendships in the Resurrection, one that does not shirk the dignity of the body, we may surprisingly but rightly turn to the status of sexual intimacy in Paradise. Or, more specifically, what becomes of that most intimate of carnal unions? Do our glorified bodies simply leave sexual intimacy behind since its earthly goal of procreation is no longer relevant in Paradise? There is no longer death, and thus no need for generation to compensate for the deficit in life. Because mortality is wholly overcome and absent from the equation, there is no inner dynamis to preserve our lives through sustenance which staves off death, just as, again, there is no place for sexual intimacy to augment the population. Earth is complete, God’s judgment is final, there are no new persons to be created. Both our generative and nutritive powers would be fruitless in Paradise.

The idea that Paradise would include an abundance of sex that bears no fruit, brings no life, drastically undermines the union of flesh and blood both on Earth and in the glorified body. Such a union is wholly unfitting, for it is something all too pedestrian, all too easily accomplished here on Earth. It is more of the stuff of Hell and its self-enclosed egos of whom each uses the body of the other for the advantage of the self to hide its own decomposition. This view of sex in the Resurrected State is clearly opposed to the sacredness of love-making by denigrating its powerhouse purposiveness to bring new life. What pleasure could an unfulfilled act of sexuality have in relation to the Beatific Vision?

But, to play devil’s advocate, is the Thomistic view incomplete when unpacking the intensity of intimacy furiously sought to be attained in the act of sexual union? Or at least, is there more to be dwelt upon regarding how sexual intimacy is transformed and carried over into the Resurrected State? If our glorified bodies mean we have eyes and ears and voices to praise God, and with such intensity, because they are infused and enriched with the blood of the Lamb which makes God exceedingly more visible to our senses, then it appears wholly at odds that we would be resurrected as eunuchs in that so-called “better place,” or, more drastically, void of sexual organs altogether. If every part of the glorified body is, through Christ’s kenosis and infixion, incarnationally united to us, what becomes of our carnality? Every aspect of our flesh and blood is raised, transformed, so that each wound is no longer a defect, and each of the senses and every aspect of our bodies praises God; then again what must we genuinely understand of our carnal intimacy? Are we simply to bypass it as inconvenient along the way to a neutralized, disembodied spirituality? But this seems to be unwise and inauthentic given how Christ beckons us with nuptial language, calling us into the intimacy of the bedchamber as Bridegroom to his bride.

Much of the glory and the folly of earthly life and human decision revolve around this sexual, hierarchically nuptial, climax. Additionally, the pro-creative power to engender another has always been the core of human existence. The tension between sex and enduring union—between sex as the chief desire to push past death and into the ecstasis of immortality, and the little death in which it deterministically resolves itself each time, is grounded in the Edenic mythos of exile and mystically rehabilitated in Christ as Bridegroom, with human intimacy residing essentially, anxiously, uneasily in between.

Sexual love is the most tragically corrosive act in the world, it draws all like moths to a flame precisely because it indiscriminately presents to those made of Earth and clay the promise of completed incarnational intentionality. In the carnal, nuptial union, we dive into the other, we encircle briefly that transfixing and transposing of the soul, and then glimpse the transfigured redemption of flesh and blood through the rupture in temporality that places the united somewhere between time and eternity. Love-making gives us a moment in climax of becoming the other as other not only immaterially but in a way that would distinguish us from the angels, specifically reflecting human beings as soul and body. It gives us a foretaste of Christ’s martyrological intentionality that accomplishes becoming the other as other both immaterially and, crucially, physically. But no human sexual act completes what it promises: bodies die down, souls retire into themselves, the union separates because it cannot sustain itself. Love-making is furiously drawn out through history, engendering more life to try again and again to free itself from the little death. Truly virtuous love-making, the relentlessly gentle and gently relentless coupling of one lover to the beloved, is perhaps the most primordial act on Earth that points to the desire for Resurrection. It enters transiently but unsustainably into the orbit of an enduring unity that alone overcomes death. What is always sought is the nuptial union of gentleness and firmness, of love being made and given, through the self-emptying of the Bridegroom to his Bride. Only Christ, as Bridegroom, completes this powerhouse tragic desire within sexual intimacy, fulfilling the making of love, or love-making, in the highest order. Our efficacious pro-creative power as participating in the eternal finds its image only in God’s pro-creative Actus, who formed us from the depths of the Earth and created our inmost beings.[29]

We could never claim comprehensively to understand how the role of sexual intimacy is transformed in the Resurrection. But we can reasonably recognize that love-making—as forming, creating, shaping love with flesh into flesh—provides on Earth the dearest and painfully sublime instantiation of a true incarnational intentionality. This acknowledgment must also cause us phenomenologically to pause on how our flesh and relationality are experienced in the Resurrected State. Perhaps Paradise is the true climax hinted at and yearned for within all love-making. In the glorified state, we finally complete the task, making ourselves unending vessels of love to fill into overflow the beloved, as the other fills us, as Christ has filled us. This intimacy is not a mirror image or a mere continued reflection of earthly union. Aquinas is right to reject generative and nutritive powers as having any purpose in sustaining Paradise. But this does not negate their roles altogether. What is reflected in our glorified bodies should actually be our bodies and souls glorified. Paradise, we can imagine, has its own love-creating, love-enshrining, love-permeating, love-exuding, love-radiating form of love-making. This again is not a reflection of earthly love-making ever in battle with death. Paradisal love-creating is the image to which all likenesses tend not by univocity but by analogy. Its capital image is Christ, the Bridegroom beckoning us with every summit of every joy within every completed end to his bedchamber.

The Christian faith has always been a faith practicing death, but now we are practicing something quite other altogether—the death of the faith. At present, such a lamentable conflation exists throughout our culture and has taken a stronghold in academia. The faith is being hounded out of existence by a tidal wave of vicious concessions that render it meaningless, dulling its beauty, and whitewashing its teachings. How then can we evangelize effectively, and reinvigorate the goodness of this salvific faith? We are all nomadic because this Earth, while at times a loving promise to be our home, is itself not. This means, indeed necessitates, that all the teachings of the faith, from the sanctity of life to the last things, lose their ardor and magnetic power when they are not presented within their proper place, within the abode of Salvation. How can we promulgate the beauty of the faith if we have not tended to its roots, to the mythos of all mythic patterns, Paradise? And by mythos, we do not mean an invented narrative, fable, or tale that ends only as a narrative, fable, or tale atop existence, but which cannot complete these yearnings. We mean the mystical wisdom so holy, inviting, and pure that it is understood only through consecrated experience. And when glimpsed, it is the ground from which spring all tales and all love songs, and every bowed head. Until we recover a fleshed-out vision of Paradise, we may indeed have theologians, doctors, maids, accountants, lawyers, plumbers, and farmers but we will not have saints, we will not have faith that drips like sap from the maple, and nectar from the comb. What is the good of a proclaimed “good life” if such goodness does not saturate our very being? To find this permeated soil, we must return to our roots, to the alpha and omega, to the Heaven that Christ’s Flesh realizes within our own flesh.

And this is the future of Christian thought. The here and now take precedence in one sense but not in another. The protracted but soon-to-be final suicide of the West can neither be understood nor survived without a renewal of the meaning of death, of the ecstasy in which Heaven has visited earth, dwells both in absence and in presence, in our flesh, forever remaking all things. With de Maistre: “Wherever an altar is found, there civilization exists.”

EDITORIAL NOTE: This essay was originally one of the twenty papers delivered at the major international conference, The Future of Christian Thinking held at St Patrick’s Pontifical University in Maynooth, Ireland in 2022. The event was hosted by the Faculty of Philosophy and organized by Drs. Philip John Paul Gonzales and Gaven Kerr.

[1] Cf. Voegelin, “The New Science of Politics,” Collected Works Vol. 5, 185.

[2] Heb 13–14.

[3] Gilson, Reason and Revelation, 70–1.

[4] Heidegger, Being and Time, §46–52.

[5] ST I-II, 17, 3, resp.

[6] Mt 22-37.

[7] Lewis, The Problem of Pain, 136–38.

[8] Alighieri, “Paradiso,” The Divine Comedy I, 64–87.

[9] Cf. St. Augustine, “Sermon 22a, 4,” The Works of Saint Augustine, 53.

[10] Cf. Mt 6”19–20.

[11] Cf St. John Vianney, “Catechism of Suffering,” The Little Catechism, 54.

[12] Cf. ST I, 62, 5, ad. 1: “Man was not intended to secure his ultimate perfection at once, like the angel. Hence a longer way was assigned to man than to the angel for securing beatitude.”

[13] Cf. SCG I, 8.

[14] See Tolkien’s letter to his son, Michael, during WWII. Tolkien, Letters, 45: “Still, let us both take heart of hope and of faith. The link between father and son is not only of the perishable flesh: it must have something of aeternitas about it. There is a place called ‘Heaven’ where the good here unfinished is completed; and where the stories unwritten, and the hopes unfulfilled, are continued. We may laugh together yet…”

[15] Cf. SCG, IV, 84.

[16] Cf. Merleau-Ponty, “Eye and Mind,” The Primacy of Perception, 170.

[17] Cf. Engelland, Phenomenology, 5–6.

[18] Cf. Levinas, Totality and Infinity, 51.

[19] Plato, Timaeus, 37c–d.

[20] Cf. ST I, 85.

[21] Cf. Engelland, Phenomenology, 45–6: “Flesh is the living body, which both feels and can be felt, both sees and can be seen.

[22] Cf. Levinas, “Meaning and Sense,” Basic Philosophical Writings, 54.

[23] Tennyson, In Memoriam, 167.

[24] Plato, Apology, 38e–39b.

[25] Cf. St. Patrick, “Lorica,” The Life and Prayers of Saint Patrick, 66–67.

[26] Cf. St. Paul, Eph 6:11–13.

[27] Cf. St. Thomas, Gospel of St. John, 1, lect. 5, 133.

[28] Cf. St Bernard of Clairvaux, “On the Song of Songs,” Selected Works, serm. 79.

[29] Cf. Ps 139:13–16: “For you created my inmost being; you knit me together in my mother’s womb. I praise you because I am fearfully and wonderfully made; your works are wonderful, I know that full well. My frame was not hidden from you when I was made in the secret place, when I was woven together in the depths of the Earth. Your eyes saw my unformed body; all the days ordained for me were written in your book before one of them came to be.