SPOILER ALERT: This review does indeed contain spoilers.

Red Welby (Caleb Landry Jones) reads Flannery O’Connor. This is not a defining feature of his, and no neighbor would probably note his reading choice. But to the viewer of Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri, writer-director Martin McDonagh’s momentary close-up of A Good Man is Hard to Find in Red’s hands early in the film is full of meaning. I suggest that it may be the key to understanding what this film is trying to say. In spite of the cycles of anger that seem to define and consume the world, there are moments of grace that shake our expectations and show another path. It is up to us to choose whether we will walk that new path, or continue down our current road.

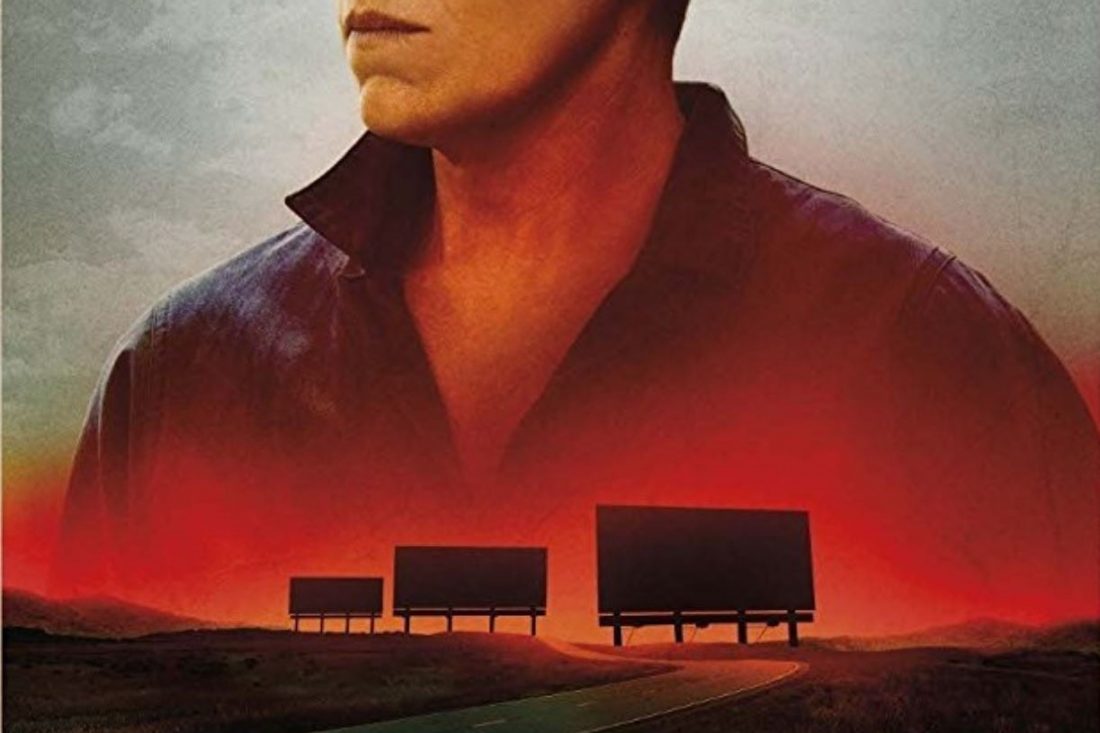

Three Billboards is the story of Mildred Hayes (Best Actress nominee Frances McDormand), an acerbic woman who rents the titular billboards outside of her southern town to call attention to the unsolved rape and murder of her teenage daughter. Mildred’s message tries to bring the town police to task, especially the well-liked Chief Willoughby (Best Supporting Actor nominee Woody Harrelson) and the idiotic, hot-headed Dixon (Best Supporting Actor nominee Sam Rockwell). Needless to say, the billboards are not a popular move in this small town.

O’Connor said of writing for an audience who didn’t share her Christian worldview, “To the hard of hearing you shout, and for the almost blind you draw large and startling figures.” McDonagh fills his story with just such “large and startling figures.” The tenor of the movie oscillates between dark and comedic, with characters’ dialogue often right on the line of humorous and devastating. It is violent, including beatings and a disturbing suicide. And at its center, there is Mildred, whose anger compels her to act, at times via a dentist’s drill, kicks to the crotch, and verbal takedowns of Catholic clergy, all in the name of her cause.

This pursuit of justice against a police force and a town that persist in misogyny, racism, homophobia, and sexual abuse is one that finds a lot of support in a modern audience and even elicits cheers from theater seats. But Three Billboards does not become a simple revenge fantasy, an exercise of the audience’s tolerance of awfulness, or even a straightforward narrative of persistence in the face of suffering. True to its O’Connor roots, the story of Three Billboards is one of an in-breaking of grace in spite of and because of these “large and startling figures.”

The trite, bookmark platitude “anger begets anger,” offered by an unlikely source of wisdom in the film, turns out to be a fitting assessment of the situation. Each time characters act in anger to gain what they desire, the result is never satisfaction; it is more anger. The cycle must be broken and there must be a realization of anger’s futility.

The culmination of anger for Mildred comes in reaction to the arson of her billboards. In an extraordinarily acted scene, Mildred’s desperation to extinguish the flames demonstrates more than words ever could exactly how much she has put into her campaign and how she has suffered before and since. Her abuse at the hands of her ex-husband, the strained relationship with her children, the guilt she feels for her daughter’s death, and finally the pain from the case’s lack of closure: Mildred has invested all of this suffering into her billboards, and now even those are being taken from her.

In retaliation, Mildred goes beyond anger and enacts revenge: she hurls a Molotov cocktail at the police station. To her, the decision is perfectly logical, even justified, because the police have burned the billboards (she believes) and, more, still done nothing for her case. The only thing to do is to send them a message: an eye for an eye, a fire for a fire.

In a parallel way, Officer Dixon functions throughout the film as a foil to Mildred. Whereas her anger and violence is apparently for justice, his is aimless and impulsive, culminating in throwing a man from a window in a mixture of grief and rage at Chief Willoughby’s suicide. It is at his low point that Dixon gets a message from beyond the grave. In a letter left for Dixon, Willoughby tells him that he would be a good man (and good cop too), if only he would let go of hate. Immediately upon reading these words, Dixon is faced with the decision to act, as he is in the police station that Mildred is bombing at that very moment. Instead of acting out of self-preservation, Dixon rescues the case file of Mildred’s daughter and makes it out of the inferno.

The intersection of Dixon’s and Mildred’s stories at the police station is a subtle entrance of something new among the large and startling figures of Three Billboards. The encouraging words of a dead man (for Dixon) and the sight of a badly burned cop (for Mildred) are the small but powerful moments of grace among the grotesque of the everyday. For both characters, a different path is revealed.

Still, Flannery O’Connor would never end things so tidily and neither does Martin McDonagh. A break in the case leads not to closure for Mildred, but to a perpetrator of another crime entirely. Once again, anger beckons Mildred and Dixon: “hunt him down anyway: it is the right thing to do.” For those on this darkened path, the choice between acting in anger or accepting grace is constant, persistent.

Whether Mildred and Dixon choose the former or the latter is left ambiguous. Will they kill this guy? They’ll decide on the way.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Jit3YhGx5pU

Editorial Note: Church Life Journal is publishing a series reviewing each of this year’s Best Picture nominees, which can be conveniently accessed here.

Featured Image: Detail taken from a Portuguese poster for Three Billboards accessed from IMDB.com, Fair Use.