Why Would Anyone Want God to Make for Tragedy?

It may not seem like much for an advertisement for God to say that God makes for tragedy. The billboard that asserts that “God makes for tragedy” seems on a par, in terms of public relations, with the billboard warning bleary-eyed drivers that “Jesus died for your sins.” The signs directing drivers off the motorway to homemade pies are more immediately appealing. It seems a much better advertisement to say with George Steiner that Christianity put an end to tragedy: in a cosmos in which death is succeeded by resurrection, Steiner considered, the terror of tragedy is at least suspended. There is no ultimate horror if all is ultimately to be reconciled.[1] Steiner of course followed Nietzsche in laying what he called The Death of Tragedy at the feet of the Cross.

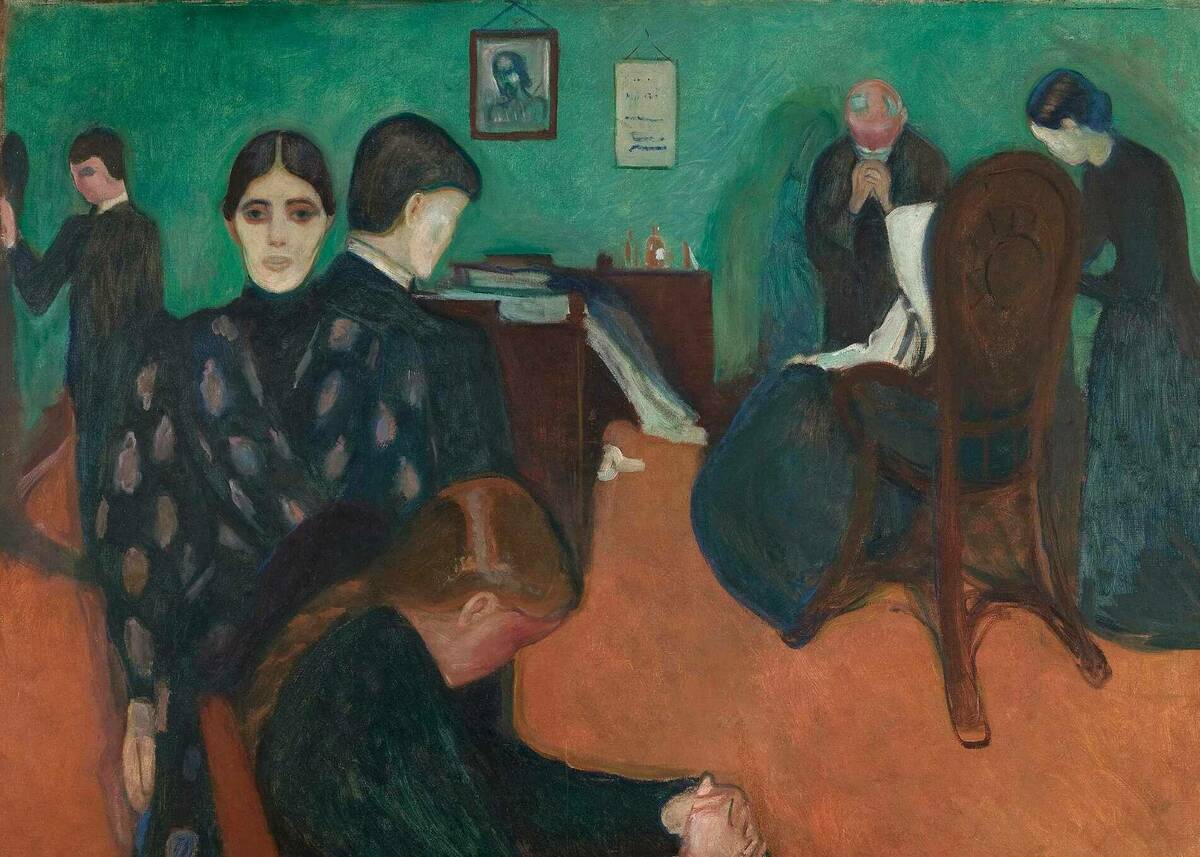

I taught theology in Presbyterian Aberdeen for a decade and a half, and do not savor anti-Protestant jokes. But this one, told to me by my good friend, gets us into the topic in a helpful way. The joke runs like this:

The Reverend Dr. Ian Paisley asked some school children to give him an example of a tragedy. One child replied, “If someone fell off a tree, that would be a tragedy.” Paisley replied that “That would not be a tragedy, it would be an accident.” A second child piped up and said that “If a bus full of children were to drive off a cliff, that would be a tragedy.” Paisley again rejected this as a false example, claiming that, “That would not be a disaster, but not a tragedy.” A third child, perhaps exasperated by Paisley’s fuss-budget approach to defining tragedy, declared that, “If you were in a helicopter and it crashed, that would be a tragedy.” “Absolutely right,” smirked the Reverend, and “How do you defend this definition?” “It would not be a disaster,” the child replied, “and it sure would not be an accident.”

I wish to propose, then, that there is a human need to articulate some of our experiences neither as disastrous nor as accidental catastrophes but actually as tragic. Pascal is speaking to this need when he describes the human creature as riven between grandeur and misery. Shakespeare addresses this same desire when Lear describes Edgar as a “poor, bare, forked animal.” My claim is not that we want tragedies to happen to us, but that we want some of what has happened to us to be tragic.

Given the unendurable weights which most human persons endure, weights which by nature are unendurable to us, we desire to be able to locate some of our experiences within the range of tragedy. No human life lacks at least one moment in which a fellow could say, with Bob Dylan, “my burden is more than I can bear.” The grandeur of the tragic hero is that his dark burden is more, humanly speaking, than he can bear.

We do not want it to be empty histrionics when we rebuff the “I’m sorry for your loss” categorization of our experiences. We do not want to recognize an interior barnstorming ham in our perception of ourselves as outrageous villains who are nonetheless, perhaps, “more sinned against than sinning.” We need to see our persistent lapses of taste, judgement, style, and the simplest morality as the fall of a hero from a very great height. We want a mysterious combination of Fate and free-will to accompany our journey beyond loss, accident and disaster into tragedy itself. We want the very gods to have plotted this, the Fates to have woven our tortured story and Teiresias to warn us. We would settle for membership of a tragic family, which passes on its superb iniquities from generation to generation. And we need our spectacular fall through criminality into much deserved suffering to be cathartic. We want to make of it a gift offering, or a thank offering, or one of the other nine different kinds of offerings in the Old Testament. We need it to be acclaimed. We want to articulate our sufferings as tragedy, and to do so without too much absurdity.

We want the genre of our human lives to fall into the category of tragedy, and not farce or fiasco. So, it is not a matter of our solitary roles: it is not just that I want to identify my autobiography with that of King Lear, or Lady Macbeth. I cannot shout at the grave like Hamlet, or roar at the desolate heath like Lear in one enormous, shrieking guitar-solo. There are many players in Macbeth, none of them escaping its tragic reach, because every aspect of the region in which it happens is regulated by the rules of tragedy. Everyone is playing the same game. The existence of Lear or Cordelia stands or falls with the reality of the domain and realm of tragedy.

The quality of tragedy in any individual life is a moment in the real existence of tragedy as a metaphysical law of the land. Tragedy is not the grandeur of the excess suffering borne by any single individual. It is an entire play of events, circumstances and persons. “They fuck you up your mum and dad,” as Philip Larkin put it, and Oedipus had parents and guardians who ignored numerous prophetic warning. Oedipus failed to forestall his fate, and in fact, freely gripped that fate: his character was his destiny. By the time he arrives at the place where three roads meet, he is the kind of person who would kill anyone at all who stood in his way.

His own free actions compound perfectly with his fate and all of his companions and the events around him conspire to make him the tragic Everyman who haunts our imaginations. He could only exist within a tragic universe, one in which Fate is utterly aloof in its ghastly ineluctable logic, and yet stoops to single out this one forked animal, and swoops down upon him, not blindly but with a perfect eye for his uncontrolled rage and arrogance.

I do not say, of course, that all of us, at all times, inhabit this deadly region. Tragedy is a shifting field of force which from time to time captures all of its in its laws. It imposes itself upon us. That does not simply mean that bad things happen to good people, though they do, but that good people, in company with others, know themselves to be burdened excessively and righteously. The weight of suffering is excessive, too much for me to bear and quite unreflective of anyone’s sense of fair-play, not sporting or rational, and yet, so entirely righteous and fitting that the bearer gains in stature with every excessive weight that is added to her load. Aeschylus could define tragedy in the formula, “pathos-mathos,” “suffering leading to learning,” because the “learning” consists in the every deeper acknowledgement of the rightness of the tragic hero’s status, his or her deepening perception that even this insanity makes sense, and is purposeful. They come to grasp the field of force which has seized them, to acknowledge its laws, and its justice.

Absolute Meaning Comes Into It

Does it follow from this that a condition of the possibility of our desire for tragedy is a transcendent god or two, who represent absolute justice, justice with a capital J? Does tragedy call for majuscule “J” for Justice God with balance and scales who can recompense all of the empirical rights and wrongs and make all of that suffering add up, so that the outcome is the uplift of catharsis, and not the flattening of deflation? When urged to desire “peace and reconciliation” in his country, a Ukrainian friend said he wanted the Russians to be “reconciled with the soil.” A flat, face-down reconciliation with the earth is all that awaits the tragic hero’s descent from his plinth, if he inhabits a naturalistic universe.

Writing against George Steiner’s proposal Christianity put an end to tragedy, the author Lucy Beckett contends, to the contrary, that there can be no tragedy in a Godless cosmos. Modern naturalism, she chides, cannot define tragedy, let alone experience it or imagine its way into it. Lucy Beckett argues that Tragedy requires a transcendent God or gods, because it requires that human life is of absolute value. If Pentheus or Macbeth do not have immortal souls, we might perhaps say, it diminishes the tragedy of their casting their souls away. Lucy Beckett takes to task those who leave the premise of God out of their definitions of tragedy. According to her, in his book on Tragedy Adrian Poole makes an observation which, “may be taken as representative of the late twentieth century’s intellectual confusion: ‘Tragedy embodies our most paradoxical feelings and thoughts and beliefs. It gives them flesh and blood, emotional and intellectual and spiritual substance. Through tragedy we recognize and refeel our sense of both the value and the futility of human life, of both its purposes and its emptiness.’ Well, which?” Lucy Beckett asks, “That having it both ways is rationally impossible does not seem to strike such writers. Either everything means something or nothing means anything. But the first requires belief in God, while the second is perhaps too frightening to be faced by those . . . without Nietzsche’s desperate courage.”[2] I suppose that many people may feel, in response to Lucy Beckett’s taunt, something equivalent to “not so fast, natural gas.”

One natural equivalent to transcendent, sublime Fate or cosmic justice which seems to work on some levels for many moderns is society itself. As an all-encompassing, unavoidable power which renders us utterly helpless and before which any lone individual is absolutely vulnerable, “society” itself seems to do the work which used to be allotted to the Fates or to a righteous Judge. Societies, collectivities, crowds and mobs, vent their violence on individuals, crucify or stone them, expel them, and by this act of expulsion, unload their violence, excreting it onto the pharmakos or victim.

By collectively unloading their inner violence onto the pharmakos, the tragic victim, societies expunge themselves of the effects of this inner violence, plagues, epidemics, and general rottenness in the state of Denmark. Thus, we may invent interpretations of, for example, the Oedipus story, in which the Thebans blame Oedipus for the plague and infertility which inflicts them, enculpate him through the figure of Teiresias, and achieve catharsis by casting their violence and thus their guilt in their erstwhile King. Behind this conception, and undergirding it, is a sociological vision of society and its rules as a kind of “immanent divinity.” In this sociologue’s vision, society is a purity cult writ large, controlling and expelling “impure” members, whose impurity makes them to represent the meaningless, dirty “surd,” which must be outed, discharged and erased. Tragedy then is a societal self-cleansing, in which the violence suppressed by rigid obedience to the rules of purity is visited upon one marked out as impure. So, the very act of expulsion of the scapegoat is a despumation, a squeezing out of the human face of the bubonic buboe.

Many Christian thinkers seem relaxed with adapting the idea that a violent mechanism of expectorating scapegoats lies at the origin of all religions excepting only Christianity itself; they see the Christ figure as superseding and sublimating the scapegoat figure, by putting an end to the violence at its origin. The cycle of violence ends when the mob crucifies God himself, and God goes to his death like a lamb to the slaughter, without opening his mouth, and pacifically withholding retaliation. So, unlike the hawkish Lucy Becket, these dove-like Christians have an olive branch to offer Dr. George Steiner: Christianity does indeed put an end to tragedy, by throwing the pacific spanner of the crucifixion into the working of the scapegoat mechanism. Again, as with the first proposal, I would advise, not so fast, natural gas. We must interrogate this notion a little.

We could ask, first, how well the notion of a “pharmakos-cleansing-mechanism” fits onto the stories of the tragedies we have: do the classical tragic stories, of the Greeks or the Renaissance masters, rehearse the tale of a mob cathartically unleashing its violence on a hapless victim, whose ensuing death disinfects his community? Fumigation for anti-septic purposes is a rational activity, so we are looking for a story in which an irrational force, mob violence, is used to channel an ultimately rational design. The closest one can think of to this story is found in The Bacchae, where King Pentheus refuses to acknowledge the god Dionysius, Dionysius hypnotizes him to LARP as a Bacchante, and then incites the women of the city, including his mother and his aunt, into a murderous frenzy, in which they tear Pentheus limb from limb.

Pentheus’s crime is his hyper-rationality, his egg-headed refusal to admit the irrational, the worship of Bacchus. The denial of devotion is met, first by a magical, hypnotic transformation into a devotee, and then by death at the hands of crazed worshippers. Though he dies at the hands of the mob, there is nothing rational, nothing disinfecting about Pentheus’s death: rather, it enculpates all of the women of the city, of pointless murder. Pentheus is like Othello in seeking to banish doubt, skepticism, belief and faith and being shredded limbless by a unholy imitation of faith, the drunken and ripped enthusiasm of the Bacchantes.

It is hard to think of a tragic hero whose death serves a pharmacological, scientific plan. Some tragic characters seem to be torn between imperatives, or rent between different versions of justice: like the dockworkers in The Wire season 2, or Iphigenia. It does not look like the rational pursuit of the excision of a cancer when the little girl, Iphigenia, is sacrificed so her Father Agamemnon can uphold his family honor by taking his ships to Troy. Other tragic characters are hubristic, mortals who comport themselves as if they were gods, like Agamemnon unfurling a red carpet.

Orestes is another who must revenge his father Agamemnon’s death, by killing his mother but must be pursued by the Furies for killing his mother. It is because the cycle of vengeance and blood revenge in The Oresteia is simultaneously rational and irrational that only a goddess, Athena, can put an end to it. What takes the tragic hero or heroine down, in each case, seems to transcend the rational and the irrational. To be absolutely innocent, like Oedipus, fated at birth to patricide and to spawning brother-sons, and absolutely guilty, like Oedipus, a homicidal guy who lusts for his mother, transcends irrationality and rationality in the direction of a kind of pure paradox of the human condition.

The question, though, is not only whether the violent mob’s medicinal expulsion of their projected scapegoat helps us to interpret those classical tragedies whose stories are imprinted in our memories. The question is whether, when we ask for our suffering sometimes to fall into the genre of tragedy, we are expressing a deep-seated need to be found guilty by our tribe, to be identified by our tribe as the source and off-scouring of all that ill-affects it, and therefore to be expelled, hurled from a cliff, stoned, fully excreted, taking with me, as I go the entirety of my tribe’s violence and malfeasance? Do I want to be the means by which my community disinfects itself by being identified as its scourge, excised like a cancer, and expelled? When I ask for my story somehow to fit into the tragic register, am I asking for my suffering to be a punishment which purifies my people?

These are not rhetorical questions which answer themselves. The profound human impulse to servant-suffering is evidenced by soldiers, and by the universal respect and reverence in which their sacrifice is held. Their sacrifice is awe-inspiring, and that means, at least, regarded as somewhat of the divine. The self-sacrifice of the soldier is not seen as hubristic or arrogant: death for the city is almost the only way a fellow can approach the immortals without inciting their jealous wrath. It is a way in which the limits the gods set on the human can be safely breached. The impulse to self-sacrifice is seen universally as a gateway to divinity. The Herculean in humanity is fulfilled by self-sacrifice, that is, our desire to labor and defeat dragons, and do the impossible on behalf of our tribe.

And yet, it would not be very meaningful to be expelled and murdered by the tribe if I am not in fact guilty. If my guilt is wholly and simply a projection of their mob-violence it would be rather absurd and meaningless to be murdered by them. The sense of my Herculean vocation as a scapegoat, depends on the justice of the charge. And who is this angry mob to victimize me, without trial? Who are they to say? Where is the justice in being the blameless, victim of mob violence, a violence which, of course, only adds to the criminality of the crowd? Is what I am looking for, in seeking to identify my sufferings as tragic, to be the blameless victim of a mob who unjustly and randomly select me for the role? Do I want to be the empty screen onto which their criminality is projected, and to carry their guilt away with me, in lieu of my own?

In myself, I seem to be both less guilty than my tribe (numerically speaking) and more guilty, in that my individual sins are qualitatively deeper than mob violence. If rather than saying, with Aeschylus, ‘the justice of Zeus is inscrutably at work here, or with Sophocles, ‘Fate has done this,’ or with Euripides, ‘the gods are to blame,’ if, rather than saying with the Greeks, that a more than human, more than cosmic force is at play in my suffering we say that society has enforced this pharmacological role, then we do not speak to the excessive quality of tragic horror. To be caught in the maw of tragedy seems to include but also to exceed being caught in a society’s determination to cleanse itself. Hamlet seems to eat, consume and absolve in his death everything that is rotten in Denmark, but his death seems more momentous and even more purposeful than cleansing the state of Denmark. What I am looking for, then, in seeking to name my condition as tragic, may include a cleansing of society, a role as suffering-servant, but it also seems to be wider.

Agency Is Important

As I said, I think Oedipus’s character is his destiny, and he exercises free-will as much as he is fated. In the Greek tragedies, the protagonist’s free-will is relatively muted, but it is still discernible. It is a sign that the inspiration of classical Greek tragedy is coming to an end when Euripides gives us tragic heroes, like the Trojan Women, who are purely and simply victims. With the great Christian tragedies of the Renaissance, free will openly co-operates with fate, as in Macbeth’s overt choice of the fate which the Witches, or their master, have in stall for him.

This must be, in part, because the great archetype of a tragic hero, for the Christian centuries, so copiously and manifestly did everything in his power to provoke his own crucifixion. Every Sabbath healing, every infringement of the Law, every hubristic assertion of his own divine power to forgive sin, is a public provocation. His entire public ministry is taken up with actions intended to trigger the Pharisees, the Scribes, the Priests, and their henchmen the Romans into executing him. Christ mercilessly instigates his chosen instruments to murder him. He is very far from a hapless, peaceful scapegoat who is seized and destroyed by the unjust violence of the Jewish mob.

If, with John’s Gospel, we place the cleansing of the temple at the outset of the mission, we may say that he engineers his death through his words and outrageous, outraging actions. Both as God and as man, Jesus Christ is wholly, actively in command of his path to death. Just as God hardened the heart of the Pharaoh, so Jesus deliberately engenders misunderstanding and hatred. No tragic hero or heroine, and especially not their archetype and model in Jesus Christ, resembles the helpless human beings whom ancient peoples used against their will as “pharmacological” experiments in ethnic cleansing. What lies at the heart of tragedy, and in the heart of the Trinity, where the Father eternally begets the Son, is an expiatory sacrifice which is actively chosen and enacted.

Burning the House Down

This claim addresses the question, why would you want God to die? What good did a suffering and dying God ever do for us? And why in heaven’s name would Christ want to make a tragic hero of himself, and thus engender the terrifying genre? The proposal that God would want to help us make pitiful tragic heroes and heroines of ourselves seems jarring and irrational. To propose that God gamely provided the conditions for tragedy seems to make the human burden heavier and not lighten matters one single whit. If we have to suffer, how does it make it better that God has to suffer as well?

A few years ago, irritation with the malfunctioning of social institutions had evoked a “burn it all down” mood in some quarters. We should drain the swamp, burn it down and start over, many people averred. John Darnielle wrote a lyric called “Going Invisible [Number] Two”:

I'm gonna burn it all down today

And sweep all the ashes awayEtch an outline on your heart

I'm gonna blow the whole circus apartReckon the remnants when they land at last

The shattered aftermath of the blast

Look for me everywhere the burn marks form

Trying to find a place to keep warm

Once we have burned it all down, Darnielle’s lyrics suggest, we will find ourselves crouching in the scorched remnants, “trying to find a place to keep warm.” What good could God do us by enabling us to burn and scorch the human condition? We do not want God huddling amongst us, many will say, trying like us to keep warm as the cold winds blow on the heath; we are looking for a God who enables us to transcend and surpass that which is tragic in our condition and circumstance. Christian thinkers make themselves rather unpersuasive, it may be said, by trying to lure us toward a God who not merely shares in our tragedies, but is the actual condition of their reality. Except in the thinnest and most metaphorical sense, the suffering God is unhelpful.

In response to these widespread objections, let me be clear that when I claim that God makes for tragedy, I do not intend to say that God set himself on fire, and thus causes us to suffer, and then sits, within that great field hospital of the Church, holding our bandage-swathed hand, and eternally yet empathetically sharing in the pain of our third-degree burns. I fully agree that a God who merely co-suffers with our excruciating pains does us no favors and offers no genuinely helping hand. But the claim I make, is rather than God himself participates in the expiatory sacrifice which the cosmos and humanity make to God.

Tragedy is pathos-mathos, that is, because learning through suffering is not a bug but a feature of our metaphysical reality. The arc of history bends toward tragedy, to the extent that it curves toward learning and deepening realism. Tragedy is not meaningful, in itself, but knowing that the tragic is part of the core of the real means knowing that suffering is a means to learning, to becoming inward with reality and the way it flows.

A Brief History of Tragic-Drama

Before there was tragic drama, before there were amphitheaters in which actors staged tragic dramas there was a universal experience of human guilt and the need to expiate it. Not, mark you, a universal sense of pollution which needs to be pseudo-scientifically or magically to be cleansed by expulsion, but a sense of having offended the gods. Not just whimsical deities, gods who take umbrage at the refusal of a sexual advance or goddesses making mortal stalkers all too cognizant of their mortality. Rather, the universal experience which underlies the much later scripting and performances of tragedy is the sense of having failed to follow the course set by the stars, and wandered outside the ordained paths.

Admittedly, primitive men and women must have sometimes felt that one needed a Jesuit casuist at hand to thread one’s ways between the varying demands of conflicting moralities. But it seemed impossible to be human without transgressing, and to transgress, to need to expiate or to receive violent punishment as recompense, seemed part and parcel of the human condition. We may say that, if comedy is born of the natural sense that we are made for heavenly bliss, tragedy is born of the historical but no less natural acknowledgement that we are bound for hell, and deservedly.

John Henry Newman gives a phenomenological description of the primitive mentality which precedes tragedy by many centuries, and which ultimately is artistically imitated in the toils of the tragic hero. Newman claims in An Essay in Aid of a Grammar of Assent,

It is scarcely necessary to insist, that wherever Religion exists in a popular shape, it has almost invariably worn its dark side outwards. It is founded in one way or other on the sense of sin; and without that vivid sense it would hardly have any precepts or any observances. Its many varieties all proclaim or imply that man is in a degraded, servile condition, and requires expiation, reconciliation, and some great change of nature . . . Also, still more directly, is the notion of our guilt impressed upon us by the doctrine of future punishment, and that eternal, which is found in mythologies and creeds of such various parentage.

He continues,

Of these distinct rites and doctrines embodying the severe side of Natural Religion, the most remarkable is that of atonement, that is, “a substitution of something offered, or some personal suffering, for a penalty which would otherwise be exacted;” most remarkable, I say, both from its close connexion with the notion of vicarious satisfaction, and, on the other hand, from its universality. “The practice of atonement,” says the author, whose definition of the word I have just given, “is remarkable for its antiquity and universality, proved by the earliest records that have come down to us of all nations, and by the testimony of ancient and modern travellers.”

What Newman places at the origin of the religious sense, that is, the need to make expiatory sacrifice, then, to make its way into the artistic stories, and staged dramas, into which the writer, and then the performers, project an archetypal human story as one in which a noble, blue-blooded hero, like Agamemmnon or Darius, enculpates himself and is required to give his or her life in recompense. Sacrifice is, clearly, a kind of ritual, and I do not mean to suggest that expiatory rituals, as such, were imitated in the creation of tragic stage dramas: no corn gods were hurt in the making of the first theatrical tragedies. At the origin is simply the sense that we have done something wrong, the all-seeing gods know about it, and the divine punishment will karmically and ineluctably hunt us down. An artistic imitation of the impulse which produces sacrificial ritual creates tragic drama. That gives us the Oresteia, the Persians, the kind of “meta-tragedy,” of Oedipus, and even down to the dramas of Euripides, in which the justice of the gods does begin to appear sometimes as unsporting or haphazard and vindictive.

I will not rehearse the story of how drama fades, disappears and is reborn with the medieval (tenth century) Quem Queretis plays, performed on Easter day in dozens of liturgical settings. Though there are good reasons to doubt if the actual origins of tragedy are ritualistic, its resurrection, through the Quem Queretis plays seems rather uncontroversial. From the French musical-comedies about Daniel and Adam, to the four great English cycles of Mystery plays, drama as play-acting in the context of a religious festival is re-created. There may be some historical connection between the Mystery Cycles all being written and performed in England, and the emergence of the greatest tragedy and comedy the world had yet seen in Elizabethan London. What is remarkable, after fifteen hundred years of Christianity, is how strictly, still, the original classical forms of tragedy and comedy retain their purity and savagery.

I place myself open to correction, but it seems as if all Christianity had to add, in this moment of dramatic creativity, was an accentuation of the freedom of the protagonists. Othello and Macbeth both are seduced and trapped by demonic forces, but they will-fully enable their own seduction. It is a seduction, not a rape. Iago and the Witches have chosen their man with precision: they know their victims to be ripe for the plucking, and yet we see these heroes seize their destiny with both hands, their own freedom fully engaged in the seduction. Hamlet must with minute protraction come to the recognition that the task imposed on him of recompensing his Father’s murder can only be achieved through his own death, if justice and not vengeance is to prevail. He recognizes the nature of his death, as a ritual expiatory sacrifice.

After the great resurgence of tragedy and comedy, from Shakespeare to Moliere and Racine, begins an experiment in abolishing the finality of the last curtain. F. Scott Fitzgerald was exactly wrong when he observed that “there are no second acts in American life.” The effort to create a second, third, fifth, eleventh and fifteenth act energizes our great enterprising modern democracies, and its artistic counterpart is the endless story of calamities in search of a happy ending. It seemed as though in a naturalistic cosmos, tragedy slides into melodrama, where there is no last act, no final pronouncement of the guilt or innocence through travail of the protagonist. The story of a perpetual, shark-leaping, quest for the reconciliation of all contrary and diverse and opposite things, is our modern melodrama. It can be called a “tragi-comedy,” a tragedy in search of a comedic ending, one which is no more unlikely and Deus ex machina, than the series of accidents and disasters which beset the protagonists. It seemed as though the yearning quest for expiation and justice was replaced by the quest for a come-back.

What happens at the same time, though, is that comedy no longer glorifies the human condition; contemporary comedy no longer expresses the deep seated vocation of men and women to parade into heaven, wearing a spangled cape, seated upon an elephant, to the sound of trumpets and gongs and the even louder applause of the saints and martyrs. Comedy seems set perpetually on its lowest register, of satire. Satire seems to have absorbed the entire, three-storied region of comedy. We have no paradisal comedy, but only the blackest of infernal commedias.

And then something rather funny happened. The more the hero of comedy ceased to be, precisely, a comic hero, and became, instead, the comedic butt, a victim of his own hapless determination to make the worst choice in every given situation, the darker our laughter became, the more the lead’s heroic status was stripped from him, as the blows rained down upon him or her, the more it seemed as if comedy was burrowing down into tragedy. It seems as if, in an ever-darker satirical portrayal of the human in its ambitions and desires, we have recreated the tragic hero, whose fate evokes horror and pity. As the satire became more brutal, cringe-making and violent, so the hero or heroine rose to the occasion, as if we must, ultimately, accord the human some justice and acknowledgement.

It seems as if the catharsis which the tragic plot used to evoke is now drawn out by ever darker satire: the satire of Michael White, in Brad’s Status and Enlightenment and White Lotus, the deadly satire of Breaking Bad, and Better Call Saul, in which the trickster hero has descended, through his own volition, into a tragic figure. It seems as if tragedy has reappeared, breaking through within comedy, and transforming the Chaplinesque fool of the comedic butt into a tragic figure. It seems as if tragedy cannot be exorcised, even within a supposedly secular and disenchanted culture.

What is happening here, I would suggest, is that the genres of tragedy and comedy have been pushed ever closer to one another. On the one hand, that gives us the mixed genre, where the tragic hero constantly pursues an ever-deferred comedic conclusion. The human as naturalistically conceived has neither the magnificence nor the humility of the heroes of classical tragedy and comedy.

On the other hand, what moves the two classical genres together by a kind of gravitational force is the ever-deepening efflorescence of Christ in our culture. We recognize, not only the ways in which he provokes his own death, but owns his self-mockery. He sends up the figure of the Messiah and the Son, by riding into Jerusalem on a donkey. He is not made a fool of, but makes a fool of himself, always in complete command of his own self-humiliation. The crucifix has germinated in our culture, leading us to perceive to see him, ever more fully, as the figure of the Fool and ever more fully as the archetype of tragedy. Christians have always acclaimed, “by death you defeated death,” but the interior appropriation of what it would mean to defeat death by death is only beginning to dawn. And so is the re-definition, the re-articulation of the tragic moment.

The Trinity Making for Tragedy

When we say that God in Christ reconciling the world to himself is the condition for the possibility of tragedy we mean that our burdens are not accidents, fiascos or catastrophes. We mean that God knows as God what the creature experiences as tragedy, and this is the source of the possibility of that experience of grandeur in misery. We mean that tragedy is an element of the modus operandi of our cosmos, reflecting something in God to which it is remotely analogous. What is negatively tragic in the creature is positively and active in the inner divine being, in its self-articulation. The self-articulation of the divine being includes the word “sacrifice,” or, the self-naming of the one divine being attributes sacrifice to the Word. In and through the self-engendering of the Trinity, an eternal lamb is slain, and this slaughter is the positive and creative condition of what, negatively and privatively in the human creature, is tragedy. We might even say that the Lamb slain is the condition of naming the fall of the angels as tragic, and not a primeval disaster or fiasco.

There is no eternal tragedy within God, nor an eternal comedy of resurrection. But there is that in God which makes for an eternal, comedic reward of eternal life, and that in God which makes for tragedy.

EDITORIAL NOTE: This essay was originally one of the twenty papers delivered at the major international conference, The Future of Christian Thinking held at St Patrick’s Pontifical University in Maynooth, Ireland. The event was hosted by the Faculty of Philosophy and organized by Drs. Philip John Paul Gonzales and Gaven Kerr. For more information see here.