The recent spate of abortion laws pushed through state legislatures across the country has been much in the news. New York now permits even full-term babies to be aborted, and the new law has rightly sparked controversy.

Forty-six years after Roe v. Wade, the abortion mindset has influenced the culture in insidious ways. I have been interested in the issue of surrogacy (and wrote about it in greater length here), and I found myself thinking of the parallels between the abortion mindset and that of surrogacy.

Gestational Surrogacy

Gestational surrogacy involves an agreement between commissioning parents and the woman who carries the baby in pregnancy, the birth or gestational mother (sometimes called the surrogate mother). The baby is conceived through in vitro fertilization (IVF) using the genetic material of the commissioning parents, a donor, or a combination thereof, and subsequently implanted in the birth mother’s womb. She then carries the baby to term, gives birth to the baby, and, under the surrogacy contract, hands over the baby to the commissioning parents, having no right or responsibility to the child. In exchange, the birth mother is paid for her “services” by the commissioning parents.

The practice is big business: an estimated $6 billion global industry, $4 billion in the United States alone. It is on the rise; sought by couples with infertility issues, singles, and same-sex couples—especially in light of the redefinition of marriage by the Supreme Court in Obergefell v. Hodges.

The practice is unregulated on the federal level, while there is little agreement on regulation across the states due to wildly differing laws from state to state. Pro-surrogacy states then become a sort of surrogacy capital, as California, for example, has become, including for international commissioning parents whose countries have placed a ban on surrogacy.

Since IVF was invented, traditional surrogacy—wherein the birth mother would be artificially inseminated with commissioning father’s sperm—has been largely supplanted by gestational surrogacy. The child of gestational surrogacy, unlike one of traditional surrogacy, would have no genetic tie to his or her birth mother. But the baby does retain that gestational tie to her. Surrogacy disregards this tie and declares it unimportant.

“My Body, My Right”

The familiar refrain of “my body, my right” for abortion is extended to the rationale that justifies surrogacy. Couched sometimes in feminist language, the argument goes that surrogacy is precisely women-applying-their-rights in action. It is her womb and it is her body; she is free to use it however she sees fit. Thus, for example, to the argument that surrogacy disproportionately involves poor birth mothers signing up (for money) to bear the genetic children of wealthy commissioning parents—hence perhaps the plane of freedom of contract is tilted more favorably than we would like to admit toward the commissioning parents, and perhaps there is an issue of exploitation of the poor—proponents of surrogacy retorts that it is patriarchal and disempowering to the women to suggest that they are anything less than free moral agents with full-fledged “decisional maturity,” as one scholar put it.

There is a deeper look worth taking on the phrase “my body.” The abortion mindset in which the culture is steeped has confused the rightly ordered meaning of that phrase. C.S. Lewis articulates the issue with characteristic clarity, through the senior demon Screwtape’s advice to junior demon Wormwood in The Screwtape Letters:

The sense of ownership in general is always to be encouraged. The humans are always putting up claims to ownership which sound equally funny in Heaven and in Hell and we must keep them doing so . . . We produce this sense of ownership not only by pride but by confusion. We teach them not to notice the different senses of the possessive pronoun—the finely graded differences that run from “my boots” through “my dog,” “my servant,” “my wife,” “my father,” “my master” and “my country,” to “my God.” They can be taught to reduce all these senses to that of “my boots,” the “my” of ownership.

And how may the possessive pronoun “my” in “my body” differ in crucial matters from “my boots”? Screwtape’s advice again:

Much of the modern resistance to chastity comes from men’s belief that they “own” their bodies—those vast and perilous estates, pulsating with the energy that made the worlds, in which they find themselves without their consent and from which they are ejected at the pleasure of Another! It is as if a royal child whom his father has placed, for love’s sake, in titular command of some great province, under the real rule of wise counsellors, should come to fancy he really owns the cities, the forests, and the corn, in the same way as he owns the bricks on the nursery floor.

The muddled thinking behind the phrase “my body” includes thinking of the body as an artifice, or raw material to be manipulated. As Robert P. George explains, it is the old 2nd century Gnostic view about the dualism of body and self now coming back to us in the 21st century, donning the disguises of the issues of our day. Thus, in surrogacy, the womb is to be rented away, and gestation is a “service” under contract, notwithstanding the deep connection between body and soul—and bodies and souls, as between the birth mother and child.

Children, Sacrificed

The pro-abortion discourse is all about women’s “rights” and hides, or ignores, the issue of children as victims. In abortion, children is the thing we do not talk about. So it is in surrogacy also. (Although a major difference, of course, is the children die in abortion, and live in surrogacy. Or, perhaps it would be more apt to say that in surrogacy, the children are commissioned into production?)

The pro-surrogacy discourse is full of talk about the commissioning parents’ wishes and desires to have children, often conflated with the parents’ right to have children. But there is not much talk about what surrogacy does to the children.

To be sure, infertility is deeply disappointing and painful. After all, the desire to have children of our own (genetic make-up) is surely written into the fabric of our being. But conflating this very worthy desire to have children with the right to have them is wrongheaded and dangerous. If having children is a right, then children are owed to us. If we are entitled to them, we should be able to procure them—and children we will get, by any means.

This line of thinking ignores how the birth mother is imprinted on the child (and vice versa), fearfully and wonderfully, only the surface of which science has begun to scratch. It ignores the longing of the soul as the child grows up never knowing his birth mother—by contract and design. Thus a child is fragmented and damaged by not being raised, known, and loved by his biological parents (that is, his genetic parents and his birth mother) in the practice of surrogacy. The problem is only compounded with the use of donor eggs or donor sperm in surrogacy, as the child is then intentionally deprived of his genetic parents and his birth mother—all of whom are his biological parents. (Especially to the extent that the identities of these parents are anonymous to the child, it leads to the further fragmentation of the child’s identity.) It also makes for charging full-steam ahead in the manufacturing of children using IVF, physical health risks to the child inherent in the process be damned.

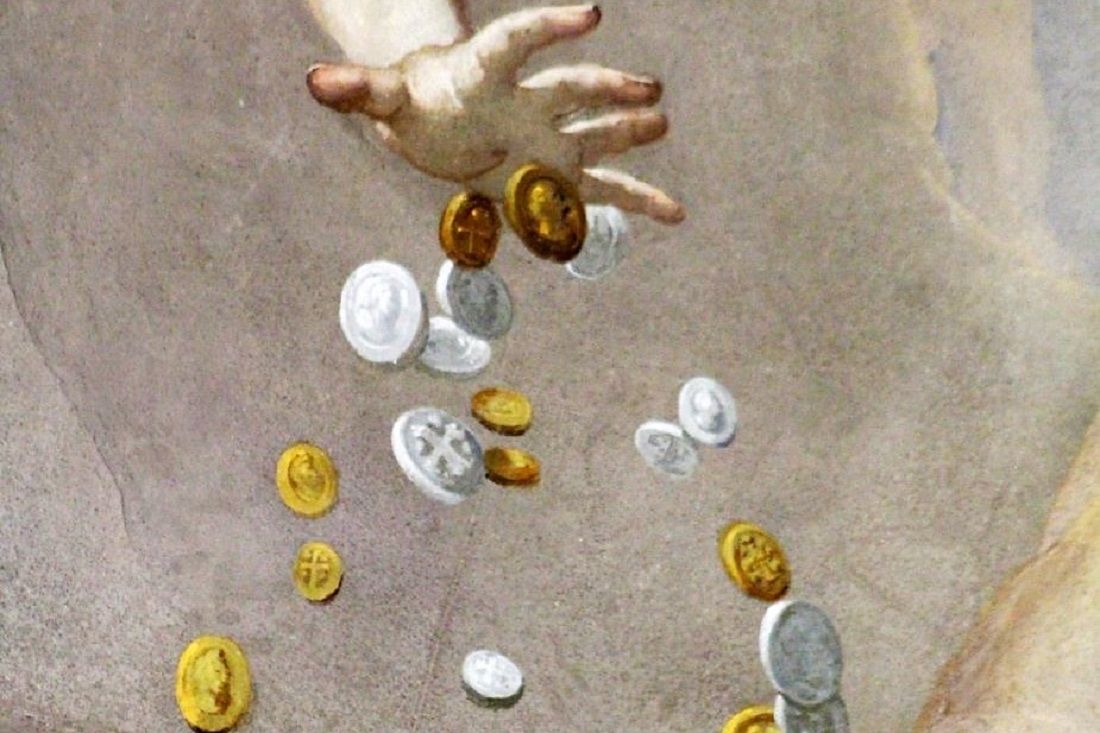

The contrast between surrogacy and adoption, wherein the child similarly grows up without his biological parents, is remarkable. In adoption, the biological parents are replaced by the adopted parents to redeem what is an already broken situation; the loss of the biological parents is not sought out. In surrogacy, by contrast, the loss of the birth mother (and again, depending on the procedure and whether it utilizes a donor egg, sperm, or both, the loss of one or both of the genetic parents as well) is the very design and nature of the arrangement. Whereas adoption serves the child, surrogacy serves the commissioning parents. Here, then, are our children, sacrificed on the altar of the Idol of the Self.

In a darkly confused world, it is imperative that the Church speak the truth in love. We proclaim Christ the Light of the World; let truth shine in the darkness. If we are made in the image and likeness of God himself, let us remember that we are hylomorphic (body-soul composite) beings; let us take care to understand well the responsibilities inherent in “my body.” Let us remember that “children are a heritage of the Lord and the fruit of the womb is His reward”; let us always treat children as a blessing and a gift, never a burden—or a prerogative. Let us raise children as whole persons; let us not fragment who they are and tear them asunder.

Editorial Note: This piece is published here thanks to the efforts of the Notre Dame Office of Human Dignity & Life Initiatives. Please take a look at the Office’s resources page.