The form of one approaching through the fog is at first ambiguous. Only two will know him: he who loves him and he who hates him. God preserve us from the sharpsightedness that comes from hell.

—Romano Guardini, The Lord

The bulk of the theological content in Lord of the World generates from a systematic series of “transvaluations” of a kind not seen in literature before Robert Hugh Benson’s 1907 novel. This fact explains much about why Lord of the World is not only recognized as one of the earliest dystopian novels in the literary canon, but also as the earliest dystopian novel with such explicitly articulated philosophical and theological themes. Transvaluation—astutely identified by Friedrich Nietzsche in his saliva-fanged critique of Christianity, The Antichrist (1895)—is a dynamic process in which systems of thought, belief, and culture organize in time in relation to a rotating point of reference.

In Lord of the World, we learn immediately in the novel’s prologue that the late modern world has been transvalued, by series of dramatic events, from a theistic culture to one that is “anti-supernatural,” a global society where “Humanitarianism” has inserted itself as the new “Pantheism”—but with the creed “God is man.” In the novel, Benson appropriates Nietzschean transvaluation to articulate and expose its core flaw: the erroneous rejection—and implicit disdain—for a transcendent source of life and meaning. He then presents an apocalyptic world where truth and authority are subtly transignified and then reoriented anew upon a deceptive political cartography.

The results are striking, not only for the way that Benson depicts the sanitized and “sharpsighted” precision with which religious persecution takes place in the 2007 setting of the novel, but for the theological authenticity that critiques such a world, one that, as Yeats will observe in a kindred spirit twelve years later, “slouches towards Bethlehem to be born.”

Transvaluation is a simple concept, but like most simple things, it has profound power. When St. Paul observes decisively in Galatians that “it is no longer I who live but Christ lives in me” (Gal 2:20) he is disclosing a transformed life, the realization of a new set of bearings from which the locus of all value flows—the truth of the Gospel and the irruption of divine relationship. Paul’s life is transvalued—transformed and sustained by the all-encompassing event of gracious encounter. For his part, Nietzsche was not so much critical of Paul’s logic as he was of the focus and referent of his logic.

After all, to discern and construct a philosophy and code of ethics that stems from a principle, experience, or a person is natural enough; but to build such things on the founder of Christianity, a movement that Nietzsche rabidly assessed in The Antichrist as “the one immortal blemish of mankind” is another thing entirely. For Nietzsche Christianity is the “triumph of the ill” and a “self-contradiction, an art of self-pollution, a will to lie at any price, an aversion and contempt for all good and honest instinct.” Similarly, for the Oliver Brands of the word—who have risen to middling power in Lord of the World—the supplanting of Christianity means ideological victory for “Humanity, Life, Truth, at last, and the death of Folly!” If Nietzsche presciently observed the philosophical “Death of God” in the late 19th century of Benson’s youth, Benson’s reply is to imagine and aesthetically fashion a setting where the murder of God can take place.

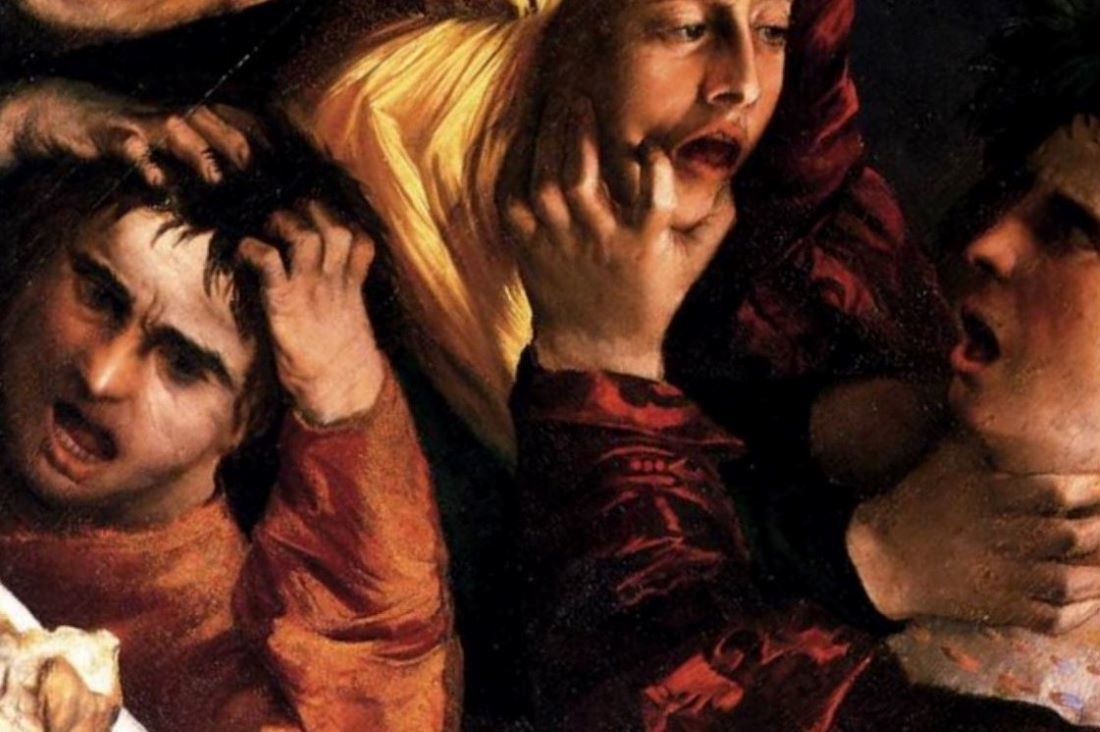

To highlight the inherently dialogical nature of transvaluation is to amplify the creative ways that Benson uses his novel to expose what Hans Urs von Balthasar develops as “theodrama”—a key aspect of his tripartite theological program. In Lord of the World, Benson anticipates and inspires other writers who will also draw on a theodramatic imagination (such as Lewis, Williams, and Tolkien) and sets the stage for a play of ideas where the stakes are, quite literally, life and death. Benson’s deft use of the doppelganger tradition as a literary device highlights this tension, which not only thickens the plot, but also exposes the shrewd insidiousness that bleaching theology out of philosophy and trivializing the religious dimension entails.

The two main protagonists of the novel—Fr. Percy Franklin and Julian Felsenburgh—are, in appearance, mirror images of one another. Midway in the narrative, Brand and his wife Mabel speak about this uncanny resemblance:

“Mabel, do you remember what I told you about the priest?” “His likeness to the other?”

Yes. What do you make of that?”

She smiled.

“I make nothing of it. Why should they not be alike?”

Clearly, Benson utilizes the doppelganger to cultivate the theodramatic conflict between lightness and shadow, between truth and lies—and to demonstrate how near in appearance these things often look to us in real time. To the enlightened denizens of the “New Religion,” Felsenburgh is the “Son of Man” while Franklin, particularly in his ultimate identity as Pope Silvester III, is the head of a baroque, backward-facing, and retrograde enterprise whose days are assuredly numbered. Since for Benson the truth of things is affixed to Christ and his Church—and this is the fundamental message of the novel—the doppelganger becomes the perfect literary tool to reveal the fraudulent heart of Felsenburgh and the “miraculous” mind that animates his new world order.

Felsenburgh’s ascension to Lord of the World, then, becomes a sham parody of Jesus as “the way, the truth, and the life” (Jn 14:16). In his quiet villainy, Felsenburgh is no rough-hewn “Lord of the Flies,” for Benson is focused on exposing the more clinical and mechanistic ways that ideology attacks the truth of Christian revelation. Clearly, this is Benson’s most sustained critique in the novel, one that reveals human complicity in the death-of-God philosophy. There is a fatigue that comes with dwelling in the complex dynamism between the natural and supernatural, especially in advanced technological societies, and it takes vigilant effort to recognize the mysterious tension between “Incarnate God and all but Discarnate Man.”

In Lord of the World, humanity has become blind to the fact that moral life, while imperfect, has been drawing on the stability of Christian theology for centuries. As Henri de Lubac sharply observes in The Drama of Atheist Humanism (1944), Nietzsche himself can be viewed as much as a canary in a coal mine, in this regard, as he can the primary perpetrator of divine assassination:

In a word, while we are full alive to the blasphemy in Nietzsche’s terrible phrase and in its whole context, are we not also forced to see in ourselves something of what drove him to such blasphemy?

The consequence of this collective amnesia in Lord of the World is the decisive denial of transcendent mystery in favor of materialist and nominalist ideologies, ideologies that first mock intellectually and then exterminate incrementally, the people of God.

Lord of the World, then, is in direct dialogue with Nietzsche; but it is also in direct dialogue with Guardini, Balthasar, and de Lubac, theologians who owe a debt, however slight, to Monsignor Benson. It is also in conversation with Father Benedict and Pope Francis, both of whom cite, at turns, Lord of the World as uniquely perceptive, indispensable, and prophetic. The myopia of human religion, especially when it becomes a vehicle for narrow ideology, not only describes the erosion of religion and public theology in the late modern age, but it also highlights the present need for a metaphysics that includes something more than the limited imagination of the “discerning subject.”

Benson’s suspicion of this kind of humanism, so well-drawn in Lord of the World, is a suspicion of any form of worship which eclipses the transcendent or reduces belief to matters of scientific materialism or spurious experimentations in social engineering. In the novel, the inverted liturgical life that replaces what went before becomes a “Catholicism without Christianity” where the “instinct of oblation without demand” is nurtured and religion is “deprived of its supernatural principle,” reduced to something akin to a rose that possesses neither fragrance nor thorn.

Such was the shape of liturgical life before Christianity and, as Benson suggests, so will it be after—degradations of religion that, as René Girard has so persuasively demonstrated and history has so consistently shown, almost always end in violence. Balthasar’s short essay, “Human Religion and the Religion of Jesus Christ” (1979), is profoundly instructive here and should be read, along with Girard’s work, as a companion piece to Benson’s novel. Balthasar meditates:

It was God’s boundless love manifest in Christ that first exposed the boundlessness of man’s No and the real atheism that does not want to be obliged to anything or to anyone, but rather wants to create man itself.

The rejection of God in Lord of the World, while cleverly shrouded behind religious demythologization and social progress, is likewise corner-stoned in this premise: the “No” that asserts and defends a self-sufficient humanism and hides the quiet rage of its violent heart. Balthasar knows well, even against the long arc of history, that this development was definitively hatched only recently:

In the religion of the Enlightenment, the truly enlightened person himself is the truth (untruth is its temporary obscurity); in the religion of Jesus Christ, he alone is the truth that exposes the sin and falsehood of man and atones for them on the cross.

This central theme—the denial of the uniqueness of Christ, specifically as savior and redeemer—intensifies throughout the novel, reaching its climactic pitch theologically not in the novel’s final scenes (read: Darth Vader in a volor), but in a chain of events experienced earlier in the narrative by Mabel Brand.

In “prayer” at a post-Christian church, Mabel begins in an ambient flow of guided reflection; next, she is moved to an epiphany, to the realization that Felsenburgh is the “transcendent total” of all humans, the “new Saviour” who bestows upon the world “the unity of all.” However, this blessed assurance is short lived. Immediately upon exiting the church, the tranquility gained in Mabel’s mock beatific vision is abruptly replaced by a holy terror. She beholds the procession of a “mob of phantoms,” as they slaughter the enemies of Humanity-Religion with the kind of barbarism and bloodlust typical of the human species.

Her empires of belief begin to burn as she witnesses the parade of scapegoats, “a great rood, with a figure upon it, of which one arm hung from the nailed hand” and next “the naked body of a child impaled” and then “a man, hanging by the neck.” In a flash, the veil of ignorance is lifted as Mabel beholds the fury that destroys the world—and this will be too much for her to endure: “There seemed no way out of it. The Humanity-Religion was the only one. Man was God, or at least his highest manifestation; and it was a God with which she did not want to have anything more to do.” Unfortunately, in the enlightened world of Felsenburgh, there is an “app” for that.

Lord of the World is a compelling narrative of ideas that, while deftly exposing the fatal flaws of a regressive turn to Nietzschean Humanity-Religion, also discloses the central Christological attribute of true “Lordship”: its non-violent heart. As in the Tantum ergo that concludes the novel, in Jesus the “newer rites of grace prevail.” His journey to the cross—and the bloodless liturgies that memorialize this sacrifice every day—expiates “the sin of the world,” as Girard observes—and which he astutely identifies as “the inability of man to free himself from his violent ways.”

Julian Felsenburgh’s ascent to Lord of the World, then, is theologically indefensible precisely because it is both philosophically counterfeit and historically blind. This does not guarantee against such a thing taking place, which, of course, is the cautionary point of Benson’s dystopian vision. Still, Benson demonstrates persuasively in the novel that the authority that comes with “Lordship” must be premised on the transcendent, “having within it all sweetness,” if it is to be valid, life-giving, and durable. As Balthasar observes: “‘No one knows the Father except the Son’ cannot be subordinated to an ‘intrinsically good’ human nature that of itself . . . knows the truth and can come to possess it.”

As something like Nietzsche's doppelganger, Benson not only pioneers new terrain in the literary imagination, but he also offers readers a solid theological aesthetic—a way to think theologically and prayerfully through and with an artistic text.

EDITORIAL NOTE: This essay is adapted from an introductory essay in the Ave Maria Press edition of the Lord of the World by permission of the author.