Come, let us return to the Lord.

He has torn us to pieces

but he will heal us;

he has injured us

but he will bind up our wounds.After two days he will revive us;

on the third day he will restore us,

that we may live in his presence.

—Hosea 6:1-2

1. In this third essay in the series my goal is to set out in very basic terms the place of Christ's crucifixion in Christian belief. As ever in theology, it is important to begin by thinking a little about the task—and, in this case, also by rooting ourselves firmly in Israel's scriptures.

To think about the crucifixion we must begin by placing it within the “economy” of salvation. An economy is an arrangement, an ordering of things towards an end. In this case we are speaking about God's economy of redemption, about that which Christians believe to reveal the true history of the world. That history is focused around a story of human failure and divine persistence. Human beings constantly fail to acknowledge their creator, practice community among themselves, or love themselves. Human beings find themselves so easily divided and at war—psychological or physical. This division, this lack of unity and harmony, results from the corruption and failure of human love that has eaten at the root of humanity since the fall.

But the story of human disunity is held within and interwoven with a story of God's working toward our restoration. Thus, in the terms of the Biblical story, Adam and Eve were expelled from Eden not simply as punishment, but as the beginning of God's redemptive work. “In many and various ways” God then worked through his Word, preparing Israel for Christ. The whole economy of Israel, Christ, and his body the Church is one, and governed toward the ultimate restoration of a harmony under God, in God.

Thus, if we seek to understand we must place Christ's crucifixion within the overall sweep of God's redemptive purpose. Doing so will help to make a few things clearer; it also creates many paths for our meditation, as the New Testament's portrayal of Christ takes up multiple strands of reflection matured through Israel's history, and invites us to explore their nuances and transformations in Christ.

As may be clear from the previous paragraph, because we are talking about God's economy it must be the case that we are talking about divine power working in the world. Grasping that economy in its details remains beyond us. How much more is it the case that when we seek to speak about the dying and rising of Christ, the very heart of that economy, we are exploring themes that will of necessity defeat our intellects. The arguments that we offer about why God acts in this way and not some other will always be arguments from fittingness.

They are arguments from fittingness because to all questions of the form “why did God not save us by doing X?” the best answers we can give are not those which claim certainty about what God may or may not do, but those which attempt to draw out why it seems appropriate and fitting that God acted in this way. Nevertheless, such arguments are not simply occasions for us merely to assert our opinions, they are occasions for us to meditate upon the meaning of scripture (and to think about the interaction of relevant passages that use different languages), to trace out ways in which the tradition has considered what is and is not fitting for us to say about God, to think about how far human reasoning may grasp the nature of God's action, and how far it must simply fail.

2. Two themes from Israel's scriptures form a particularly important part of the symbolic universe within which the earliest Christians described the cross, and those two themes will help us here. The first is the practice of sacrifice. We do not need here to try and set the long history of sacrifice in Israel's history. We can focus for now on the practice in the temple in Jerusalem. Once a year Israel's high priest entered the Holy of Holies in the Temple to sprinkle the blood of a sacrificed bull and a goat on the front of the altar, the “mercy seat” in the temple, and to offer incense, for the sins of the priest, for his family and for Israel as a whole (Leviticus 16, following Moses's own sacrifice at Exodus 24:1-8 establishing Israel's covenant with the Lord). This practice of offering to God was, of course, not merely an Israelite practice, but an expression of something deep within human nature—the practices of gift-giving to one another, and of offering to a deity are probably as old as the emergence of homo sapiens sapiens.

Although this offering is frequently understood by modern readers only as a practice designed to placate a capricious (and possibly vindictive) God—the sort of practice that in post-Enlightenment times can easily be interpreted as a “superstition”—a more careful look can reveal to us three things. First, sacrifice finds its heart not in the destruction of what is sacrificed—the killing and burning of an animal for example—but in the setting apart of what is sacrificed for God. Second, setting apart something for God is not a goal in itself, but symbolic of the true sacrifice, the sacrifice of the broken heart (Ps 50:17)—a symbolism seen also in the way that Leviticus 16 prescribes the symbolic transference of sins to a goat who is then sent into the wilderness. Third, the purpose of sacrifice is not simply to give something to God, it is to restore harmony between God and creation, and to celebrate God's glory. In doing this sacrifice aims at revealing the true nature of reality, showing us the truth of the relationship between God and creation, the nature of God, and the foundations of true human community.

As the late Anglican theologian E.L. Mascall noted:

In being offered to God in sacrifice a creature is simply fulfilling the law of its being as a creature . . . It is made by him and for him: its esse is both esse a Deo [existence from God] and esse ad Deum [existence to God]. The sacrificing of a creature to God is the ritual expression of its ontological status.[1]

Indeed, we can easily take one step further and say that the offering of praise to God is one of the ends of human existence, and one of the ways in which human beings are in the image of God. Just as the Son comes eternally from the Father and eternally returns in love to the Father, so too we are able to love God, to return love to our creator. As created beings, attention to the creator is thus a likeness of the eternal relationship between Father and Son. Given the course of human history, the returning of love must now also be a confession of contrition, an expression of our role in all that does not witness to God as creator.

3. Key passages in the latter part of Isaiah speak of one who is sent by God to gather Israel, and suffer for Israel. It is this one who will also be “a light to the nations, that my salvation may reach to the end of the earth” (Is 49:6). But, primarily, the one whom scholars have long termed “the suffering servant” comes to restore Israel to its Lord: “The Lord says, who formed me from the womb to be his servant, to bring Jacob back to him, and that Israel might be gathered to him" (Is 49:5). But before we assume too easily that this servant is one individual, it is important to note that the term speaks both about an individual and about one who represents Israel, one who in some sense is Israel. Thus, for example, at the beginning of Isaiah 44, the Lord addresses “Israel, whom I have chosen” and the addressee through the next few verses is clearly Israel the people.

The suffering servant, in the famous description running across Isaiah 52-53, is the one who will be “lifted up high,” the one who is also “despised and rejected by men; a man of sorrows and acquainted with grief” (Is 52:13 & 53:3). Not only does Isaiah say “surely he has borne our griefs and carried our sorrows,” but also, “he was wounded for our transgressions, he was bruised for our iniquities; upon him was the chastisement that made us whole, and with his stripes we are healed” (Is 53:4-5).

This language was taken up by the earliest Christians to identify Christ. One of the most important and yet mysterious equivalences that is made in these texts concerns the divine glorification. The suffering servant reveals the Father (Is 49:7) and the Lord says “you are my servant, Israel, in whom I will be glorified” (Is 49:3). To “glorify” is to honor someone or something, to praise their value. In the case of human beings this may often involve a certain deception, presenting someone as having far more significance than is actually their due—as when the lackeys of a dictator praise him or her as the mightiest ruler ever. In the case of God praise is never unwarranted, as that praise is always a revelation of only a little of the truth that is God.

Of course, we must also think carefully about what we praise. Where is God's glory seen in these texts? When he is raised up high and his lack of beauty is seen, when he bears the stripes that heal. The truth and faithfulness and love of God is seen in his servant bearing our griefs, and in his lack of what too easily counts as beauty among us. For Christians these prophetic passages speak of Christ, and in so doing so they link for us glorification and suffering, as well as identifying the servant as one and yet as a whole people. Only in Christ will these mysterious equivalences reach their culmination.

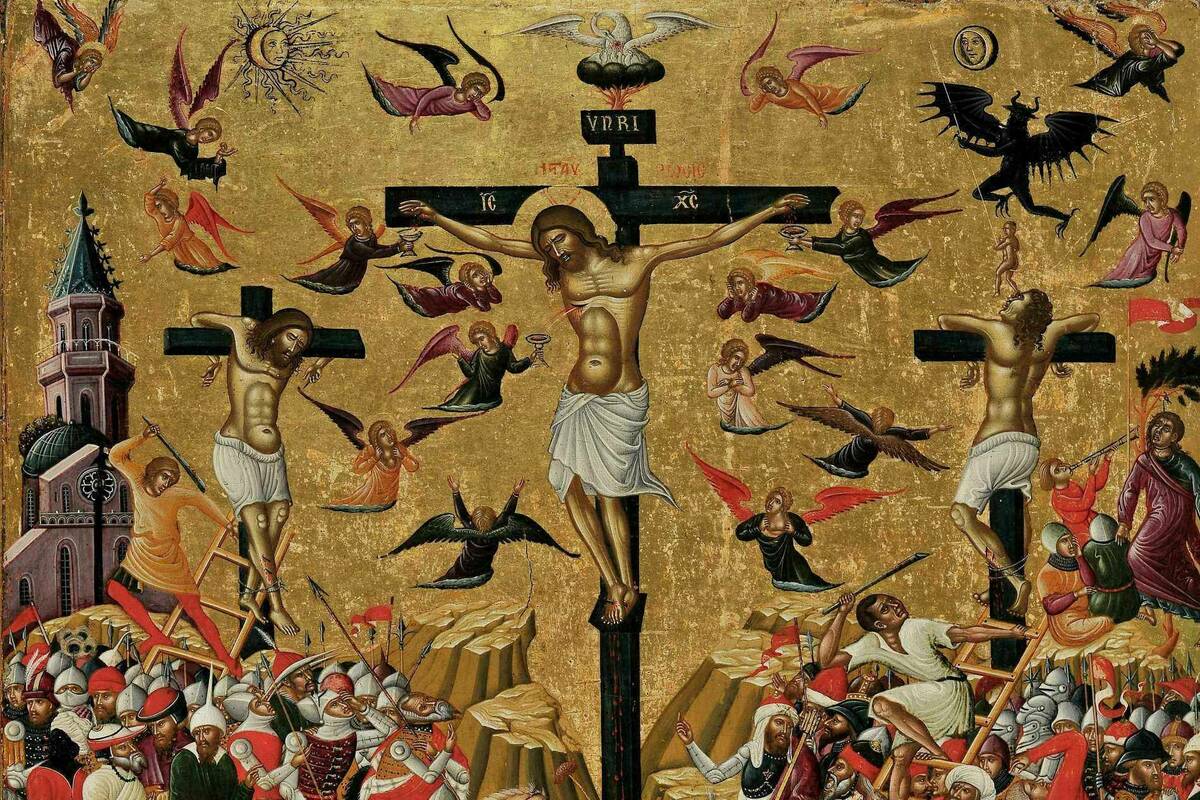

4. With these thoughts in place we can turn to Christ’s death on the cross. That we are justified in using the term “sacrifice” may be shown by drawing attention to the many ways in which the New Testament speaks of Christ as a sacrifice, and as offering himself (for a few examples see Jn 1:29; Rom 3:25; Eph 5:22; Heb 9:12, 14 & 10:12; 1 Jn 2:2). These texts provide us with a number of different terms and images, which we do not need to explore individually here. To understand how Christ is the “lamb of God,” a “propitiation,” and how his own blood stands in for the blood of the sacrificed animals in the temple, we first need to focus on three fundamental points: his love, his status as the Word of God, and the Word's taking of a human nature.

First, then, remember what a true sacrifice is. At the heart of Christ's sacrifice is not his physical body, but his love. The Catechism says: “It is love ‘to the end’ that confers on Christ's sacrifice its value as redemption and reparation, as atonement and satisfaction. He knew and loved all of us when he offered his life.”[2] Christ's love is aimed always at glorifying the Father, at revealing God to be mutual love.[3] Christ's love, though, has many dimensions.

It is, for example, a love tinged with sadness over humanity's distance from God, and willing to take on appropriate human repentance. When Christ is baptized by John the Baptist, he does not need himself to be purified of his sins, for he had committed none. Rather, he accepts a symbolic baptism of repentance (see: Mk 1:4), one in which he identifies himself with Israel's need to repent (following a long tradition in which Israel's prophets had done the same).[4] In identifying himself with repentance Christ identifies for us not only the need to atone for sin committed but also the centrality to created existence of an acknowledgment of our creator. Thus, when we seek to understand Christ's sacrifice we must always remember that it is rooted in Christ's humility before the Father, and in his love.

Second, Christ is the Word of God. We must, most obviously, always bear in mind that Christ is not only sent by the Father, but also sends himself. We must remember that not only is Christ the sacrifice, but he is also the one who accepts the sacrifice because he is one with the Father in the Trinity. These observations do not mean that we somehow stop talking about Christ as sacrifice; such language is deeply embedded in the New Testament, and it is consequently embedded in our liturgical worship. It means, rather, that when we use the language of sacrifice we must always turn our minds to the Word being one with Father and Spirit and reflect on Christ's sacrifice as rooted within the life of the Trinity.

Third, Christ is the Word-made-flesh: not God the Word dwelling in a distinct human person. And yet sometimes we must speak of the Word and the Word's flesh distinctly. Here we should say that the Word offers his own humanity to the Father. The Word's sinless humanity, infused with the Spirit, constantly sustained by its union with God, constantly gives itself over to that Word, and constantly glorifies its creator. Because the humanity of the Word is the Word's own, we are not speaking here of a parallel to one who sacrifices something that is not full his own; the Word's own humanity offers a perfect sacrifice of love. Of course, in this sense, the whole of Christ's life is a sacrifice of humble love toward the Father. We shall return to this observation under point five.

These three principles help us to understand how Christ is able to offer himself, and his body, to the Father as a true sacrifice which restores us to communion with the Father—effecting an at-one-ment between the Father and his creation.[5] Christ suffers a bloody and painful death not because the Father needs this death, but because in the face of such a love the forces of evil in the cosmos conspire at his ultimate rejection. But the death Christ dies stands, in direct contradiction of what those evil forces sought, as a sign of his perfect love to the end, his willingness to give all for us. Christ did not step away from the path that led to the cross, but his humanity, constantly giving itself over, in the Spirit, to the economy of the Father, accepted this horrific end.

This means of death is also intensely symbolic, through his bloody self-display Christ shows us in absolute humility, for example, the true nature of the worldly power we so easily idolize. But, remembering the Trinitarian context of this event we should say that divine love is not shown us as a result or consequence of what happened on the cross; divine love is the cause of what happened on the cross (e.g. Mt 20:28; Col 1:19-20).

Christ accepts in himself responsibility for all human sin and separation from God, he understands the true character of that separation in the way that none of us can. He offers himself as a penitent in our place, and feeling that separation and contrition in a way we could not because he is also the Word, the one who knows the Father truly. How he may know the Father during his life and suffering is one of the great mysteries of Christianity, but it is because Christ possesses that awareness that he understands the true nature of the divine judgment and the true nature of divine love.[6]

Christ is not “made sin” for us (2 Cor 5.21) in the sense that the one without sin changes his status to one with sin, nor in the sense that God just pours out on Christ the wrath that otherwise should justly have been poured out on us. Rather, founded in the eternal love of Father for Son, and Son for Father, the Son assumes flesh and offers through his body true praise, and true repentance for human sin, for that which has separated humanity from God. In this life of praise and love he offers his body as a true sacrifice for sin, and the Father accepts it. Khaled Anatolios very helpfully argues that we must emphasize not only the transference of the penalty for sin to Christ on the cross, but also the transformation that happens when Christ takes on that penalty:

Christ assumes that penalty, not in the form of a visitation of divine wrath on a sinful humanity, but rather in the form of a communication to Christ's contrite and thankful humanity of both God's absolute rejection of sin and his forgiving love.[7]

This transformation is not a temporally subsequent event, a communication of love following his acceptance of suffering, but a transformation identical with Christ's standing in our place. This transformation, rooted in Christ's “love to the end” is the heart of his sacrifice, and it is also demands that this piece needs a fifth section and cannot end here.

5. Christ's sacrifice has a eucharistic character and end. In Luke, at the last supper, Christ “gives thanks” over the bread and the wine as they are consecrated—the Greek verb is eucharisteo. The same verb is used by Mark and reported by Paul at 1 Cor 11:24. Christ's act of giving thanks is an expression of his love, humility and thankfulness to the Father, it is an act of glorification, an act that points us once again to Christ's love to the end. But the thanksgiving at the heart of the sacrament of the Eucharist is more than just a model for our own thanksgiving because we are drawn by Christ into his own thanksgiving.

In the Eucharist Christ opens up to us his own sacrifice on the cross and unites us with him, so that in every Eucharist we die and rise with him, into him. The Second Vatican Council's document on the Church, Lumen Gentium, famously states, “As often as the sacrifice of the Cross by which ‘Christ our Pasch has been sacrificed’ is celebrated on the altar, the work of our redemption is carried out.”[8]

The Catechism offers us the fundamental theological links here:

The cross is the unique sacrifice of Christ, the “one mediator between God and men.” But because in his incarnate divine person he has in some way united himself to every man, “the possibility of being made partners, in a way known to God, in the paschal mystery” is offered to all men.[9]

“In some way” is an important phrase. This is a mystery beyond our comprehension; divine power is at work. But because Christ draws us into himself, the one sacrifice of Christ on the cross is also the establishment of the eucharistic community, the establishment of a community of those in whom individual wills are gradually reshaped toward the final eternal glorification of God. The transformation of penalty of which we spoke above is also an incorporative act, drawing in all who will die and rise with Christ.

This involves no repetition of that one sacrifice on the cross, as we hear in one of the Easter liturgies, “he is the sacrificial Victim who dies no more/ the Lamb, once slain, who lives for ever”; it is into the one crucifixion and resurrection that we are drawn.

St. Augustine of Hippo, writing in the early fifth century famously wrote:

Since, therefore, true sacrifices are works of mercy . . . and since works of mercy have no object other than to set us free from misery, and make us blessed; and since this cannot be done other than through that good of which it is said, “It is good for me to be very near to God” (Ps 3:28): it surely follows that the whole of the redeemed city—that is, the congregation and fellowship of the saints—is offered to God as a universal sacrifice for us through the great High Priest Who, in his Passion, offered even himself for us in the form of a servant, so that we might be the body of so great a Head.

He adds:

In this form he is our Priest; in it he is our sacrifice . . . This is the sacrifice of Christians: “we, being many are one body in Christ.” And this also, as the faithful know, is the sacrifice which the Church continually celebrates in the sacrament of the altar.[10]

We are in Christ, but if so, not only he, but also we are offered on the altar. When a priest celebrates the Eucharist in memory of Christ, Christ also celebrates—in Christ we become a sacrifice to God. Our loves are not perfect, our giving of ourselves constantly fails, but because we are in Christ we become an acceptable sacrifice to the Lord even as we are also in need of constant forgiveness and transformation. Existence in Christ, then, always encompasses the distinction between Christ, the head of the body, and us, the people who follow after as his members. We have been given a regime of sacramental signs through which we share in Christ's life and acts, through which we are drawn towards our head. He is both really ours in those signs, and yet awaits us at the end of time.

But, finally, this is not only true with reference to the cross. Lumen Gentium also states: “We are taken up into the mysteries of his life, we are made like to him, we die and are raised to life with him, until we reign together with him.”[11] In the late thirteenth century the Franciscan writer Ubertino of Casale wrote:

The whole life of Christ in the world was, as it were, one most solemn Mass, in which he himself was altar and temple, priest and host. As God he himself accepted the sacrifice according to his human nature, and he himself offered his very self according to the nature he had assumed.[12]

The whole life of Christ, of which the cross, resurrection and ascension constitute the culmination, is sacrifice, is an act of thanksgiving, and we are drawn into that life as a whole.

Suggestions for Further Reading

Khaled Anatolios, Deification Through the Cross. An Eastern Christian Theology of Salvation (Grand Rapids MI: Eerdmans, 2020)

Bruce D. Marshall, "The Dereliction of Christ and the Impassibility of Christ," in James F. Keating & Thomas Joseph White OP, Divine Impassibility and the Mystery of Human Suffering (Grand Rapids MI: Eerdmans, 2009), 246-298.

Matthias Scheeben, The Mysteries of Christianity, tr. Cyril Vollert SJ (St Louis, MO: Herder, 1947), chp 16 & 17.

Thomas Weinandy, Does God Suffer? (Notre Dame IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2000), esp. chp. 9.

[1]. E.L. Mascall, Corpus Christi. Essays on the Church and the Eucharist, 2nd ed. (London: Longmans, 1965), 89. The full quotation reads: "in being offered to God in sacrifice a creature is simply fulfilling the law of its being as a creature. God is both its efficient and its final cause, its alpha and omega, its beginning and its end. It is made by him and for him: its esse is both esse a Deo and esse ad Deum. The sacrificing of a creature to God is the ritual expression of its ontological status."

[2]. Catechism of the Catholic Church, §616.

[3]. For a theologian who makes this theme the framework for understanding Christ's sacrifice see Matthias Scheeben, The Mysteries of Christianity, tr. Cyril Vollert SJ (St Louis, MO: Herder, 1947), chp. 16.

[4]. The theme of Christ's repentance and contrition is developed with particular clarity by Khaled Anatolios, Deification Through the Cross. An Eastern Christian Theology of Salvation (Grand Rapids MI: Eerdmans, 2020).

[5]. Textbook accounts from the last century often speak of different "models" of atonement. This is very problematic talk, and I will not use it here. On the one hand, it fails to recognise that often theologians meld together a variety of different languages for speaking of Christ's sacrifice, as do the Scriptures. On the other hand, the language of "models" can make one think that in supposedly offering one a given theologian thinks that hse or he can thereby "understand" that sacrifice.

[6]. For an excellent orientation to discussion of this deep mystery see Thomas Joseph White OP, The Incarnate Lord. A Study in Thomistic Christology (Washington DC: Catholic University of America Press, 2017), chp. 5.

[7]. Anatolios, Deification, 419. The same section of Anatolios's book also offers a clear and generous response to the range of theologies that might be termed theories of "penal substitution."

[8]. Lumen Gentium 3, quoting 1Cor 5.7.

[9]. Catechism, § 618.

[10]. Augustine, Civ. 10.6. Translation from The City of God Against the Pagans, ed and trans. R.W. Dyson (Cambridge: Cambridge University press, 1998), 400.

[11]. Lumen Gentium 7.

[12]. Quoted in Denys the Carthusian, De vita et regimine curatorum, art. 14, in Doctoris Ecstatici D. Dionysii Cartusiani Opera Omnia, vol. 37 (Tournai: Typus Cartusiae S.M. De Pratis, 1909), 142-3: Omnia namque quæ fecit ac passus est, meritoria nobis fuerunt. Ideo tota vita Christi in saeculo quasi una solennissima Missa fuit, in qua ipse fuit altare et templum, sacerdos et hostia. Deus acceptans sacrificium ipse est secundum divinam naturam, ipse idem offerens se ipsum secundum naturam assumptam.