Advent Sunday

by Christina RossettiBEHOLD, the Bridegroom cometh: go ye out

With lighted lamps and garlands round about

To meet Him in a rapture with a shout.It may be at the midnight, black as pitch,

Earth shall cast up her poor, cast up her rich.It may be at the crowing of the cock

Earth shall upheave her depth, uproot her rock.For lo, the Bridegroom fetcheth home the Bride:

His Hands are Hands she knows, she knows His Side.Like pure Rebekah at the appointed place,

Veiled, she unveils her face to meet His Face.Like great Queen Esther in her triumphing,

She triumphs in the Presence of her King.His Eyes are as a Dove’s, and she’s Dove-eyed;

He knows His lovely mirror, sister, Bride.He speaks with Dove-voice of exceeding love,

And she with love-voice of an answering Dove.Behold, the Bridegroom cometh: go we out

With lamps ablaze and garlands round about

To meet Him in a rapture with a shout.

Christina Rossetti’s “Advent Sunday” provides a framework for the Christian, longing to celebrate the season of Christmas with upright heart. Her poetry does so by inviting the Church to reassume her identity as Bride of Christ, longing for union with the Bridegroom.

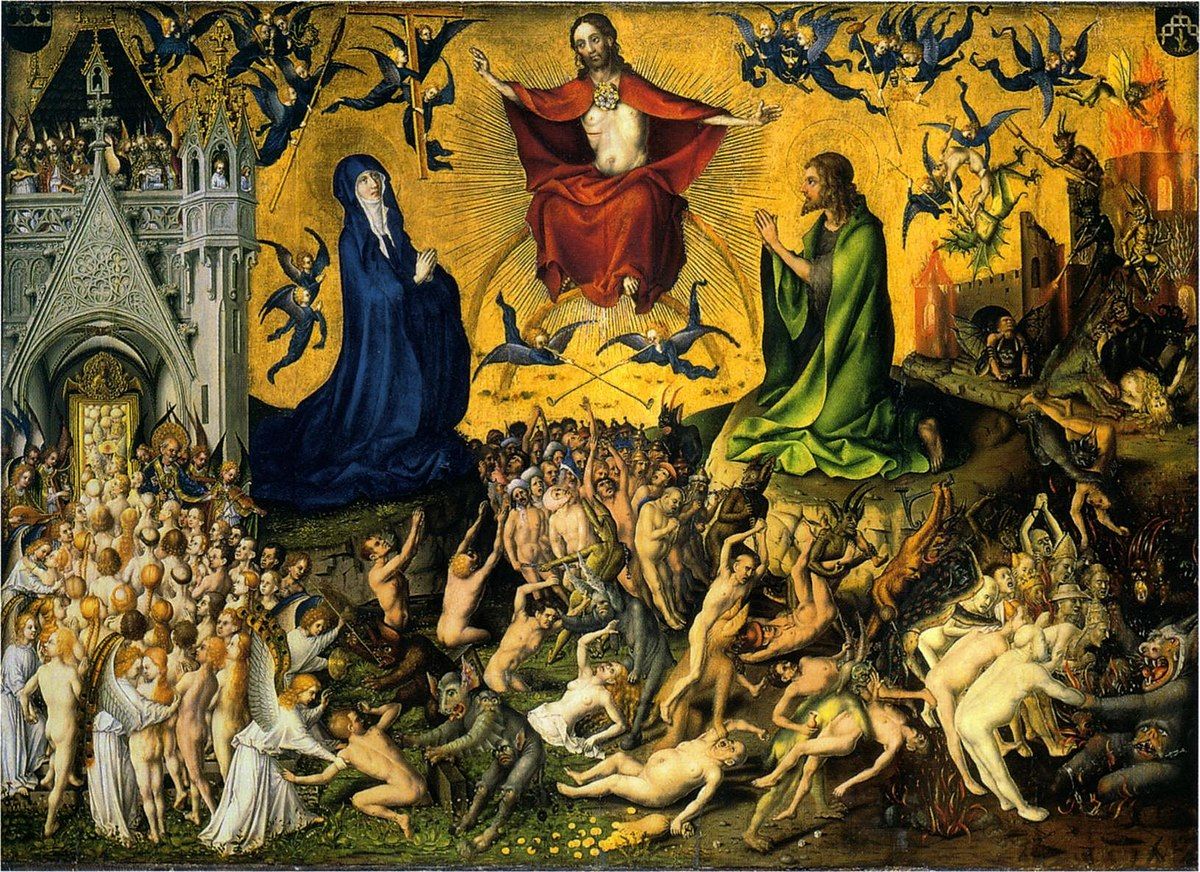

Rossetti commences her “Advent Sunday” through reference to apocalyptic imagery. The reader is transported to Matthew 25, the parable of the ten bridesmaids. This is a parable of judgment, in which those carrying unlit lamps—lacking oil that will last through the long night—are insufficiently prepared to greet the Bridegroom. Those with darkened lamps are left outside the wedding fast, told by the Bridegroom: “Truly, I say to you, I do not know you” (Mt. 25:12).

This first stanza of the poem begins with an appropriate degree of fear, of trepidation, a sense that God will judge the nations. The collect for the 1st Sunday of Advent in the Book of Common Prayer states:

Almighty God, give us grace that we may cast away the works of darkness, and put upon us the armour of light, now in the time of this mortal life, in which thy Son Jesus Christ came to visit us in great humility; that in the last day, when he shall come again in his glorious Majesty, to judge both the quick and the dead, we may rise to the life immortal.

The Bridegroom is coming to judge, and the Church must be prepared. The poem performs the sudden, interruptive nature of such judgment. It could be at midnight or at the crowing of the cock, both references to Peter’s denial of Christ in the garden. Peter himself could not have imagined this moment of judgment, this occasion in which he would deny the identity of the Bridegroom. The Church, during the season of Advent, must come face-to-face with her own forgetfulness, her own sluggishness before the Bridegroom. Lest we become like the foolish bridesmaids, like Peter himself.

But Rossetti’s poem then takes a turn. Too often during penitential seasons like Advent and Lent, members of Christ’s body may conclude that avoiding judgment is really up to us. But, it is Christ who comes running to us, seeking us out. It is not just that we have to learn to desire us absent any affection from God. Rather, God desires us. Advent is the season in which we make space for God’s wooing, rather than our self-sufficiency.

The reader then assumes the position of being desired by God, of longing for the kiss of the Bridegroom. The Bride, as Rossetti declares, knows not just the hands of the Bridegroom—an image of the crucifixion related to judgment. She knows his side. Rossetti is drawing on themes related to both creation and the crucifixion. Eve comes forth from the side of Adam. She is “bone of my bones and flesh of my flesh” (Gn. 2:23). From the side of Christ sleeping on the cross, comes forth blood and water. This is an image of the Church, the Bride of Christ born from the sacrificial love of the Word made flesh.

The Bride, if she recognizes the loveliness of the Bridegroom, will seek to respond in love. Rossetti turns to three Scriptural motifs in describing the Bride’s desire. She is Rebekah, coyly unveiling her face on her nuptial day before the Bridegroom, Isaac. She is Queen Esther, once orphaned, assuming the role of spouse of King Ahasuerus. Yet most importantly, the Church is the Bride from the Song of Songs.

Here, the eros of God for the beauty of the Bride assumes prominence. The Bridegroom gazes into the dove-eyes of his Bride, recognizing there mirror, sister, and Bride. Jesus Christ gazes into the eyes of his Bride, his beloved, and sees himself. He is the one who has assumed the fullness of the human condition. And therefore, he recognizes in his Church the full possibility of what it means to be human. Christ, as the Word made flesh, longs to be united with the Church in all of her humanity.

Now Christ speaks. The Bride does not respond with terror, for the Bridegroom speaks with dove-voice. He coos. He woos. And the Bride offers back words of love.

The end of the poem returns to the moment of apocalyptic judgment. But it has now been transformed. The reader of the poem is no longer a spectator at the wedding. The reader has become the Bride, on the way to the wedding feast. We wait with lamps, not for any Bridegroom. But our own Bridegroom—Jesus Christ.

In this sense, the season of Advent is about preparation for Christmas. But, Christmas as should be clear will not relate only to the coming of the Christ child in our midst. Instead, Christmas is the season in which the Word has become flesh, in which the great wedding between God and humanity has come about. The judgment of Advent, which we discover in Rossetti, is not a monstrous one. Instead, it is the judgment of a lover who comes forth for his beloved. Advent is a season in which we adorn ourselves as God’s beloved, to greet the Bridegroom who comes to kiss us with the mercy of eros.

Editorial Statement: Church Life Journal will feature commentary on devotional poetry during the season of Advent.