In this way the love of God was revealed to us: . . .that he . . . sent his Son as expiation for our sins

—1 John 4:9-10

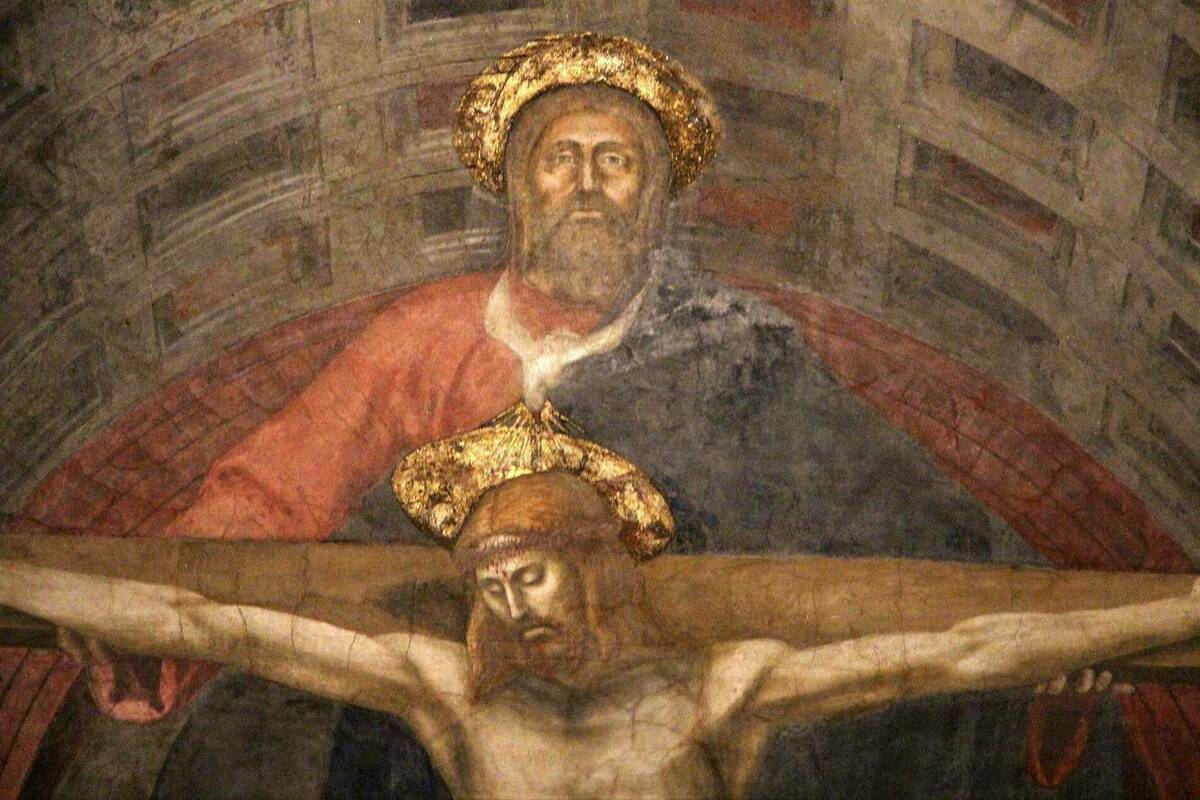

The theme of atonement takes us to the very heart of the mission of Jesus Christ. Revealing the love of God as a mortal man, while bearing the conditions of sin-wrought estrangement, God’s Son atoned for the sins of the whole world (1 John 2:2). Atonement is the form that the love of God takes in his Son, Jesus Christ, under sin-wrought conditions—a love than which no greater can be conceived.

In John’s Gospel, those who observed Jesus weeping over the death of Lazarus correctly interpreted the meaning of his tears: ‘‘See how he loved him’’ (11:36). This recapitulates the confession of faith in response to Jesus’ mission, which culminates in his own Passion and death: ‘‘See how much he loves us!’’ This is the key interpretation of the Cross event, which Jesus reveals to his disciples, whom he calls friends: ‘‘No one has greater love than this, to lay down one’s life for one’s friends’’ (John 15:13). And the apostolic Church makes this central to her profession of faith: ‘‘God proves his love for us in that while we were still sinners Christ died for us’’ (Rom 5:8). ‘‘The way we came to know love was that he laid down his life for us’’ (1 John 3:16). A theology of atonement is not complete unless it issues from and serves to elicit the profession of faith: ‘‘See how much God loves us!’’

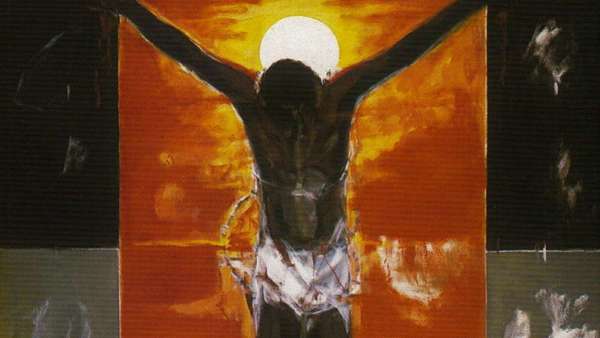

Clearly, the love of God made manifest in Christ’s atoning Passion stands at the center of Christian witness. Christians in every age should know and witness to the God of Jesus Christ in precisely these terms. Not only that, but this witness is to be directed to all mankind: ‘‘The Church, following the apostles, teaches that Christ died for all men without exception: ‘There is not, never has been, and never will be a single human being for whom Christ did not suffer.’’’ In our days, this Christian conviction is poignantly conveyed by Pope Saint John Paul II, in a way that draws attention to the profound existential impact it is meant to have on every human person. ‘‘Man,’’ he says, ‘‘needs to know that he is loved, loved eternally and chosen from eternity.’’ He needs to be made aware that ‘‘the Father has always loved us’’ in sending his Son to deliver us from evil. When everything would tempt us to doubt the existence of a God who is rich in mercy, precisely then ‘‘the awareness of the love that in [Christ crucified] has shown itself more powerful than any evil and destruction, this awareness enables us to survive.’’

It should be cause for concern, therefore, that a conspicuous characteristic of much of contemporary theology is the absence of efforts to explain the Cross event as a work of atonement. Despite the fact that the Church’s Scripture, doctrine, and worship all sanction the faith-conviction that Christ by his Passion and death atoned for sin, once for all (Heb 9:26), this understanding of the Cross event has largely fallen out of favor. Among theologians, one can detect an unmistakable reserve—even embarrassment—with regard to the idea. And things are not hugely different in the world of parish faith formation. On most occasions when the Scripture readings at Mass testify expressly to the atoning purpose of Christ’s Cross, the priest or deacon proves masterful in avoiding the subject—even on Good Friday, when the prophecy of the Suffering Servant (Isa 53) is read as prelude to Saint John’s Passion account.

We may assume that behind this pattern of avoidance is the view that the message of the Cross as atonement clashes with the sensibility of many today. Nonetheless, just as Christ had to challenge the expectations and mindsets of his interlocutors, so Christians may not sidestep the task of challenging and transforming the perspectives of their audiences.

For his part, Pope Benedict XVI is alert to the trend among Christians to distance themselves from the doctrine of the Cross as atonement. Indeed, he challenges it in the first volume of his masterwork, Jesus of Nazareth, where he observes: ‘‘The idea that God allowed the forgiveness of sins to cost him the death of his Son’’ is widely seen as repugnant. Benedict then goes on to identify reasons for this trend. The first reason he singles out is ‘‘the trivialization of evil in which we take refuge.’’ We seem to have a very small estimate of human guilt, the menace of evil, and the damage it causes. We presume that we sinners know all about sin, that we can properly ‘‘contextualize’’ it from our own point of view; after all, we are its perpetrators. To the degree that the trivialization of evil holds sway in our minds, the message that Christ’s Passion and death is a work of representative atonement cannot but strike us as an overreaction on God’s part.

Besides this inaccurate assessment of sin, another troublesome reason for the modern aversion to the idea of atonement lies in a distorted depiction of God the Father’s role in the Cross event. Ever since the seventeenth century, and indeed well into the twentieth, a trend arose among theologians and preachers to portray God the Father as a celestial child abuser vis-à-vis Christ crucified, as someone who unleashes violent fury on his Son for sins of which his Son is innocent. Such a portrayal of the Father gained a foothold in Catholic circles under the influence of Jansenism. Here are but two examples. The first is from a sermon by a Catholic bishop, Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet: God the Father,

beholds him [Jesus] as a sinner, and advances upon him with all the resources of his justice . . . I see only an irritated God . . . The man, Jesus, has been thrown under the multiple and redoubled blows of divine vengeance . . . As it vented itself, so his [the Father’s] anger diminished. . . . This is what passed on the Cross, until the Son of God read in the eyes of his Father that he was fully appeased . . . When an avenging God waged war upon his Son, the mystery of our peace is accomplished.

Our second example is from a conference by Reverend Gay: ‘‘Fervently emulous of her holy Son, Mary offers herself with him . . . She abandons herself without reserve into the hostile and incensed hands of the divine creditor . . . whom only the most drastic shedding of blood can satisfy . . . Behold her locked in combat with this irritated and hostile God.’’ Regrettably, many more texts could be brought forward that imagine God the Father as thirsty for vengeance and demanding the Passion and death of his Son to calm his rage.

An adequate response on our part must counter the trivialization of sin without erroneously thinking that the magnitude of sin is best measured by the magnitude of divine vengeance. We will argue, instead, that it is above all in encountering the fathomless love of God that ‘‘our heart is shaken by the horror and weight of sin.’’ If evil can be known only in relation to the good, this must mean that we cannot know the whole truth about sin apart from the whole truth about the supremely good God—a twofold truth that is consummately revealed in the Cross event.

Closely coupled with the above-mentioned faulty notion of divine wrath is another mistaken view, one that fails to preserve the primacy and generative modality of the Father’s love in relation to the work of atonement. In this fallacious view, the Son’s role is to win back the Father’s love for the human race. But this is at odds with the Johannine proclamation that ‘‘God so loved the world that he gave his only Son’’ (John 3:16) and the Pauline passage that declares: ‘‘God [the Father] proves his love for us in that while we were still sinners Christ died for us’’ (Rom 5:8; cf. 8:31-34). If we are to do justice to the biblical testimony, we must show that the Son’s work of atonement is the result of the Father’s love. It does not result in the Father’s love being revived or jumpstarted, as it were.

At the opposite pole from (and to some extent in reaction to) these flawed portrayals of the Father are those readings of Christ’s Passion that outright reject the idea that it achieved atonement. Typical of this stance are the remarks of Peter Fiedler: ‘‘Jesus had proclaimed the Father’s unconditional will to forgive. Was the Father’s grace, then, insufficiently bountiful . . . that he had to insist on the Son’s atonement all the same?’’ Theologians and preachers in this camp appear unable or unwilling to make understandable Saint John’s claim that we have come to know that God is love precisely in view of God’s sending his Son as atonement (1 John 4:8-10). To the sensibilities of many like Fiedler, the two prongs of this claim (God the Father is love and the Son’s Cross is atonement) are mutually exclusive. They feel compelled to dismiss ‘‘atonement’’ as a religious notion that cannot be squared with the revelation of the love of God in the New Testament.

An adequate response to this camp must shed light on the question as to why God’s merciful love does not onesidedly effect forgiveness but calls for the atonement of sins. It must uphold the biblical claims while making the mystery of atonement sufficiently transparent to the mystery of God who is caritas, and, in the first place, to the mystery of the Father.

EDITORIAL NOTE: This essay is an excerpt from Atonement: Soundings in Biblical, Trinitarian, and Spiritual Theology (pages 13-19), courtesy of Ignatius Press, All Rights Reserved.