Why does the pilgrim walk? What—or who—is it that she desires to find, and whose antecedent desire prompts and incites and propels and attracts her to set out upon the journey in the first place? It is the pilgrim-mystic, as de Certeau’s Mystic Fable puts it, “who cannot stop walking and with the certainty of what is lacking, knows of every place and object that it is not that; one cannot stay there nor be content with that. Desire creates an excess. Places are exceeded, passed, lost behind it. It makes one go further, elsewhere” (299).

As a mother sometimes prone to fits of nostalgia, I think of the heady strangeness of the seventh chapter (“The Piper at the Gates of Dawn”) of The Wind in the Willows (1908). Rat and Mole, some of the novel’s most charming animal protagonists, embark upon a journey when they hear the “thin, clear, happy call of . . . distant piping” from Pan’s flute. The beauty of the god’s music is to them an utterly ineluctable summons. The flute’s music renders them “transported,” “trembling,” “possessed,” “breathless,” “transfixed.” “Since it was to end so soon,” Rat confided in Mole, “I almost wish I had never heard it. For it has roused a longing in me that is pain, and nothing seems worthwhile but just to hear that sound once more and go on listening to it forever.” Yet despite their painful longing, still they keep on listening and rowing, listening and rowing, until they come finally to worship the god in the holy place of the forest island, their “eyes shining with unutterable love” (Grahame, 133–148).

As a scholar and a poetically oriented theologian (sometimes prone to fits of nostalgia), I think of Dante, who Pope Francis has called “the poet of human desire” and whose Divine Comedy is simply a masterclass in beauty and holy desire. Dante’s earthly desire for Beatrice, his long-lost love, is gradually transfigured over the course of his pilgrimage through hell, purgatory, and paradise into a holy eros which redirects him from Beatrice toward the love of God, “the Good/beyond which there’s no thing to draw our longing” (Purgatorio XXXI. 22–24). And what a lovely thing it is that it is nothing other than Dante’s childhood crush on Beatrice that brings him on a journey of conversion that culminates ultimately in a direct vision of the triune God. As the Roman playwright Terence’s ancient saying goes, "I am human, and I think nothing human is alien to me" ("Homo sum, humani nihil a me alienum puto"). Dante comes to see that the transience of Beatrice’s physical beauty cedes to the glories of her blessed participation in the Beauty of God which will never, ever fade. And yet her transparent mirroring of God’s divine Beauty makes her more rather than less herself, more rather than less concrete and particular, rebuffing with force any sense that there is or could be an antagonism between human and divine goods. As Pope Francis wrote on the seventh centenary of Dante’s death, the poet-wanderer

pondered his life of exile, radical uncertainty, fragility, and constant moving from place to place, sublimated and transformed his personal experience, making it a paradigm of the human condition, viewed as a journey—spiritual and physical—that continues until it reaches its goal. Here two fundamental themes of Dante’s entire work come to the fore, namely, that every existential journey begins with an innate desire in the human heart and that this desire attains fulfilment in the happiness bestowed by the vision of the Love who is God.

One of the central claims here is that the nature of beauty presents itself to human perception precisely as a call and as a provocation. Beauty, at least understood in its most metaphysical and theological sense, bears within itself a capacity to awaken and to stir human beings from their stupor into the “glorious unrest” (Sammon, 1) of something like Book 10 of Augustine’s Confessions (“Late have I love you, beauty so old and so new, late have I loved you. . . . I tasted you, and I feel but hunger and thirst for you!”). It has been commonplace for thinkers down through the ages, from Plato to contemporary phenomenologist Jean-Louis Chrétien to have made much of the rich etymological connection between the Greek word kalon (the “beautiful”) and kalein (“to call”); beautiful things are designated as such “precisely because they call us and recall us” (Chrétien, 3). Beauty, however, does not leave us unfulfilled forever. It does not leave us perpetually in the role of the addressee, the wanderer, the exile, the pilgrim. Rather, as with Dante, beauty refers our wayward, sometimes insufficiently courageous desires toward the God who ultimately gathers the human being together into her final, unified and integrated shape and restores her to her proper home.

There are many others who could be added to this great cloud of witnesses. While I will be prioritizing mostly philosophical, theological, and literary sources, there is of course also a rich biblical tapestry that could just as easily be marshaled to illustrate the capacity of the call of Beauty to provoke a restlessness and desire which ultimately draws and gathers the human being into her final, unified and integrated shape. A few examples here will have to suffice (already beautifully explicated with greater depth elsewhere). God’s divine speech of the first book of Genesis summons the whirling, watery chaos of the unformed world into shape and order; God’s call summons Abraham and the wandering people of the desert into the nation of Israel; the artisans in Exodus were filled with the creative “Spirit of God” to bring beauty, design, and craftsmanship to the beautiful holy objects of the Tabernacle; aesthetic themes are likewise present in the Song of Solomon, many of the Psalms, the transfiguration of Jesus, the apocalyptic visions of John’s Apocalypse, and many more besides.

In the history of philosophy, specifically as emerging in the medieval period, the classical transcendentals—truth, goodness, unity, and sometimes but interestingly not always beauty—are called such because they exceed or “transcend” specific categories of existence which divide reality up. Transcendens in Latin means “that which surpasses something.” That they are universal properties of being itself (properties of being qua being and convertible with being) means for many philosophers that the transcendentals “co-inhere”: so where we find truth, there too will we find goodness, unity, and beauty. Where we find goodness, we will thus find beauty, truth, and oneness, and so on and so forth (although notable figures like Plato and Plotinus, for instance, did not identify the Good and the One).

I am most interested in drawing out the intimate relationship between Beauty and the Good. As we shall soon see, this close friendship between Beauty and the Good—though they are not exactly identical—appears in spades in Christian thinkers like Pseudo-Dionysius and Thomas Aquinas, with such an equivalence sometimes in the latter as to make it seem as if Beauty as such were not on his radar at all! The reason that I am interested in the relationship between Beauty and Goodness in the Catholic intellectual tradition is because it is tied almost without remainder to love and to desire (c.f. Aquinas, ST I-II q.25. a.2). Aristotle defined the Good as “that which all desire,” an idea which St. Thomas Aquinas placed centrally in his treatment of the transcendental of Goodness in the Summa. In the Rhetoric, Aristotle argued that beauty is that which is desired for its own sake (Rhetoric I c.9 (1366a 33). Eros (desire) and amor (love) provide the center and motive force of both everyday aesthetic experience as well as the history, philosophy, and theology of aesthetics from the ancient Greeks to today. Plato, Plotinus, Augustine, Gregory of Nyssa, Pseudo-Dionysius, Aquinas, Dante, Ratzinger, von Balthasar: all entangle the phenomenon of beauty with the phenomena of love and desire. Any rehabilitation of the category of beauty is, therefore, a synonymous rehabilitation and transfiguration of the category of desire.

In the Christian theological tradition, in contrast to some of the ancient Greek forms of thought we will consider, properties of being like Goodness, Truth, and Beauty do not simply have to do with philosophical systems or abstract ideas floating around in the platonic ether but are understood primarily to be predicates or divine names of God. That is, God is Being itself, Oneness itself, Goodness itself, Truth itself, and Beauty itself. Even as oneness, goodness, truth, and beauty are genuinely (only but derivatively and partially) expressed or manifest in created things, it is God alone who instantiates these properties fully and who is the proper condition for created things (which are God’s effects) to participate in them at all. So beauty is not simply one feature among others that can be observed and appreciated subjectively, in the privacy of one’s own taste and aesthetic judgement but is, in its most robust understanding, a divine name for God.

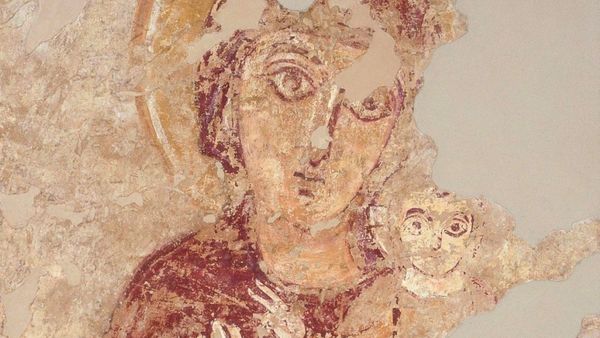

Furthermore—and this obviously distinguishes the Christian position from pre-Christian philosophy which allies beauty, desire, and the divine—in the Catholic intellectual tradition, beauty and all measures of beauty have ultimately got to do with Christ. If the ancient philosophers suggest that beauty is a spiritual, ideal form beyond the concrete instantiations of the temporal world, it is Christianity’s singular and staggering claim to the Incarnation of the eternal God in Jesus Christ that reaffirms the goodness and the beauty of the material: of flesh, body, earth, water, wine, and bread. No wonder Bonaventure places “the dying man on the cross” at the top of his own ladder of ascent in The Journey of the Mind to God. Likewise, Catholic theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar’s theological aesthetics positions Christ as the “very apex and archetype of beauty in the world” in no small part because “the glory of Christ unites splendor and radiance with solid reality” (GL I, 69; 124). The beauty of Christ’s life and teachings called, summoned, attracted, and gathered together his disciples; it still calls, summons, attracts, and gathers his people around the eucharistic table.

Through a series of unfortunate events in the history of ideas traceable to British empiricists like Hume (“Of the Standard of Taste”) and Locke (Essay Concerning Human Understanding), this robustly metaphysical, theological, and Christological understanding of beauty as a transcendental has gradually devolved into a much more impoverished understanding where beauty is now primarily understood in terms of private judgment, a cosmetic or superficial phenomenon of “prettiness,” too subjective or socially constructed to have any real purchase on universal concerns (the idea that beauty is only “in the eye of the beholder”) or else excessively entangled with decadent pleasure such that too much interest in it seems to be a piece of tawdry self-indulgence. The loss of beauty’s metaphysical status also initiated the ghettoizing of modern aesthetics into a separate and rationalistic discipline rather than being something expressive of the whole of reality or the structures of reality.

In his book Elements of Christian Philosophy (1960), French Catholic philosopher Etienne Gilson (1884–1978) called beauty the “forgotten transcendental” (159–63). But what exactly has been lost in terms of the “forgetting” of the metaphysical status of beauty? Why should it make any difference to the average person if it has been forgotten? In other words: what exactly are the stakes? Balthasar (1905–1988) spent his entire career arguing the case that the status of beauty actually makes quite a big difference in the way we live. On the very first page of his seven-volume The Glory of the Lord, Balthasar writes that “beauty is the word which shall be our first . . . we no longer dare to believe in beauty, and we make of it a mere appearance in order the more easily to dispose of it. . . . We can be sure that whoever sneers at her name . . . can no longer pray and soon will no longer be able to love” (GL I, 18). Balthasar laments the loss of the ancient, biblical, and medieval view of the cosmos as luminous with mystery and divine presence. In an age of rationalism and empiricism, the cosmos has been naturalized, desacralized. In many cases, this shift has resulted in forms of religion which are purely ethical coupled with the sense (after Kant) that human beings simply have no access to the realm beyond the visible, observable, sensible universe. What is “real” has devolved into that which is subject to strict laws of empirical verification. So for Balthasar, there is really something at stake in the neglect of beauty as a serious player not only in the field of ideas but also for normal everyday life. In short, without beauty, we have lost contact with the real.

A Balthasarian aesthetic characterizes the encounter with beauty as both a moment of “perceiving”—interestingly, the word here is wahrnehmen, or “seeing what is true”—and “being enraptured,” carrying within itself the dynamic and attractive force of its own evidentiary power and causing the perceiver to be “shocked,” “dazzled,” “overtaken,” ecstatically “transported” beyond herself and her own capacities, and ultimately invited eschatologically into a full participation in God’s glory (GL I, 17–127). Without beauty, Balthasar thinks, “the springs and forces of love immanent in the world are overpowered and finally suffocated by [an exclusive focus on] science [and] technology . . . the result is . . . a world in which power and the profit-margin are the sole criteria, where the disinterested, the useless, the purposeless is despised, persecuted and in the end exterminated—a world in which art itself is forced to wear the mask and features of technique” (GL I, 114–15). Here Balthasar makes the connection not only between beauty and gratuity—beauty being the “‘just-is-ness’ of things”! (Schindler 2017, 350)—but also between beauty and love.

Philosophically speaking, beauty is already somewhat strangely located between the objective features of the appearing phenomena and the subjective human response to it, which is simultaneously intellectual, affective, spiritual, and physical (c.f. Aquinas, ST I q.5, a. 4). Beauty comes to us through the full bodily sensorium when we see, hear, touch, taste, and smell; it engages our imagination, stirs our memory, awakens us spiritually, conjures bodily, physiological effects, and gives us pleasure. Indeed, the classical definition of beauty from Thomas Aquinas is “that which, when perceived, pleases or gives delight” ("id quod visum placet", ST I q.5. a.4 ad. 1).

Others have noticed this strangely “comprehensive” and “all at once-ness” of the experience of beauty: “rather than simply stimulating a reaction in our brain that produces a feeling, or appealing to only one dimension of human nature, perhaps to the relative exclusion of others, it appeals [all at once!] to the whole of us, no matter how opposed the aspects of our nature may appear to be”: mind, soul, and bodily senses are all engaged as beauty

“gathers us up” into a whole, and thus forestalls, or heals, the tendency to fragmentation. Beauty engages our mind and our senses at once, enlisting them as it were in the common project of perceiving beauty; as they pursue this project, the highest and lowest parts of our nature converge in a single point. . . . In this, beauty represents a remarkable source of hope; it is, so to speak, a transcendent call that call be heard by the most flesh-bound ears (Schindler 2018, 40).

A Christian aesthetic can preserve the goodness, even the sensuality, of human bodily sense experience, even as it refers it always to its proper depth dimension. Neither form nor splendor appears without the other.

We must give sensuality and erotic desire up to holiness. But if we do, it is returned to us whole and entire, reflected in the light of divine Beauty who calls us ecstatically out of ourselves towards the transcendent (and, thus, however, counter-intuitively) more toward the essence of who we truly are. Perhaps we ought to be more like Alyosha, the young monk from The Brothers Karamazov, who gazes upon the sky, “full of quiet, shining stars” in the “fresh and quiet” night of a “luxuriant autumn,” and throws himself upon the dirt of the earth in an act of profound gratitude. “He did not know why he was embracing it,” Dostoevsky writes, “he did not try to understand why he longed so irresistibly to kiss it, to kiss all of it, but he was kissing it, weeping, sobbing, and watering it with his tears, and he vowed ecstatically to love it, to love it unto ages of ages.”

So before we continue along the well-traveled road toward philosophical, literary, and theological sites that deepen and suggest beauty’s metaphysical significance, let us find some good solid footing on that which all of us already know. And I do not mean what we know conceptually, but what we know with our feet firmly on the ground, at a more intimate, visceral, personal, even bodily level. What we already know, just in virtue of our being human beings, is what the experience of beauty feels like. This is accessible, easily and immediately, for every single one of us, whether or not we have ever read a single page of Plato, Augustine, or Dante. The experience of beauty has no pre-requisite.

***

Back in February, when my hometown of South Bend, Indiana was still languishing under what felt like a permanent state of dirty snow, I ordered (far too many) seed packets from the Baker Creek Heirloom Seed Company, as something of an act of hope. My winter doldrums were soothed by reading through the names in the catalog list: amaranth, arugula, aster, balsam, barley, bee balm, bells of Ireland, borage, boysenberry, burdock, calendula, chamomile, chrysanthemum, columbine, dahlia, echinacea, nasturtium, the list of plants almost composing a poem, a litany. This past September, with late summer edging into early Fall, with cool mornings and warm, sunshiny afternoons, the sunflower seeds that I had planted in the cool and promise of May stood majestically between eight and ten feet tall. Henry Wildes and Double Sun Kings and Autumn Beauties all came up together in a glorious jumble and provided home, shelter, and food for bees and American goldfinches. And I could not stop looking at them. I never grew tired of looking at them. It is not as if I was waiting for them to do anything, or provide me with some useful or profitable information, or even, as with my bumper crop of tomatoes and cucumbers this summer, give me anything really substantial to eat. Rather, I regarded the sunflowers in a mode of absolute gratuity, contemplating without expectation those magnificent, endlessly fascinating heliotropes that followed the sun all day with their attentive, cheerful faces turned toward the corollary giftedness of its rays. Balthasar writes:

The whole world of images that surround us is a single field of significations. Every flower we see is an expression, every landscape has its significance, every human or animal face speaks its wordless language. It would be utterly futile to attempt a transposition of this language into concepts. Though we might try to circumscribe, even to describe, the content these things express, we would never succeed in rendering it adequately. This expressive language is addressed primarily, not to conceptual thought, but the kind of intelligence that perceptively reads the gestalt of things (TL I, 140).

To look at them—and I know saying this probably approaches cliché—made my heart soar. I could actually feel it in my chest. But it also, in a very real way, made my heart sore. The homonymic potential here between “soar” (S-O-A-R) and “sore” (S-O-R-E) is very apt, because in my own experience of beauty, if I am paying good attention, it really is something of both: a cocktail of bliss and pain together, and inextricably so. It is possible I am just more sentimental than most, but I would guess that I am not the first or the only person who has ever been brought to the point of tears or at least a lump in the throat by a perfect sentence in a book, an expertly rendered line of a poem, a subtle strain of music, an ethical or selfless act, a stirring cinematic scene, a moment in the liturgy, or the sight of some overwhelming phenomenon in the natural world. I get this precise feeling, for example, whenever I rewatch the cosmic creation in Terrance Malick’s The Tree of Life set so hauntingly to Preisner’s “Lacrimosa,” or when I reread the last scene of Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov, when Kolya implores Alyosha at the grave of his little friend, “Can it really be true as religion says, that we all shall rise from the dead, and come to life, and see one another again, and everyone?” Your mileage may vary with what it is exactly for you that provokes this feeling. But I think you all probably recognize what it is that I am trying to describe.

We should also recognize that this sense of painful but paradoxically delightful longing is often accompanied by an awareness that whatever beautiful phenomenon we are perceiving is at the very same time something passing away. Even as I beheld my sunflowers swaying in the golden September air, impossibly tall, impossibly vivid against the blueness of a perfect sky, I could sense their precarity. I knew their petals would inevitably loosen and fall, as they have; the goldfinches would rob them of their seeds, as they did; too soon another December’s snow will cover what little is left of their stalks, in a front-row performance of Hopkins’ “barbarous beauty” of the season’s end, as in his poem “Hurrahing in Harvest.”

Likewise, the symphony hurtles toward its ending, and the audience, having been duly transported, must stand and gather their programs and jackets and depart the concert hall; the vibrant sky streaked with purples and oranges and pinks fades over the horizon to the darkness of night; the characters in The Brothers Karamazov will gather after little Ilyusha’s funeral for their pancakes and celebrate the promise of the Resurrection, after which I must close the book and return it to the shelf. When such experiences come to their natural end, I find myself poised at least on the precipice of wistfulness if not entirely given over to it, wanting something still that I cannot quite articulate and which the phenomenon itself cannot deliver.

Sometimes—probably most times—we try to extend an aesthetic experience simply because we do intimate just how fragile moments of experiencing the beautiful can be: we might stare a beat longer in order to fix the vision within our memories, or take a photograph, or record the audio of a song or a performance, or maybe make a sketch in a pocket notebook. Moreover, there is usually an accompanying impulse to share whatever beautiful thing we have encountered with others: we upload the photo to social media or send it to our family group chat, or if we are artistically inclined, we paint it or maybe try our hand at writing a few lines of poetry. Elaine Scarry’s On Beauty and Being Just articulates this replicative phenomenon with clarity and winsomeness: “What is the felt experience of cognition,” she asks, “at the moment one stands in the presence of a beautiful boy or flower or bird? It seems to incite, even to require, the act of replication. . . . Beauty brings copies of itself into being” (3).

So why is a genuine experience of beauty something that almost universally provokes this profound sense of pain, tenderness, vulnerability, and longing within the human heart? Why is our attentive witness to the truly and extraordinarily beautiful accompanied by that almost imperceptible collapse in the chest, the intake of breath, the sacred pause to let a little private pinprick of woundedness register internally? And why is the experience of beauty so fecund and generative, prompting copies of itself? There may well be physiological or psychological reasons that can speak to these experiences which are common enough to be widely recognizable, but I am curious about the philosophical and theological accounts of the connections of beauty with pain, particularly an experience of pain expressed as longing or desire which cannot be sated.

It turns out that our bodies are surprisingly good philosophers. The association of beauty, pain, and (often erotic) desire has quite a long history in the Western philosophical tradition, spanning all the way back to philosophical dialogues like Plato’s Symposium and the Phaedrus. One of the most beloved and popular speeches in the Symposium is a creative origins myth told by the comic poet Aristophanes, who weaves a narrative about the origin of desire. He tells us that human beings were originally spherical, with two heads, and four arms and legs, but because Zeus wanted to control them, he cut them all in two. After that, they spent all their days in an awful state of longing for their other halves, “weaving themselves together” with one after another, unsuccessfully chasing that primordial and elusive feeling of perfect unity. Aristophanes says that this “is the source of our desire to love each other. Love is born into every human being; it calls back the halves of our original nature together; it tries to makes one out of two and heal the wound of human nature” (191D). Even in this pre-Christian text, Plato has Aristophanes acknowledge that love, this desire for complete wholeness and union, is not merely a desire for pleasure or sexual or emotional intimacy, but rather for something mysterious that is impossible to name. There are people, Aristophanes says, “who finish out their lives together and still cannot say what it is they want from one another. . . . It’s obvious that the soul of every lover longs for something else; his soul cannot say what it is, but like an oracle it has a sense of what it wants, and like an oracle it hides behind a riddle” (192D). Aristophanes’ speech goes on to imagine that Hephaestus, god of metallurgy and welding, approaches two lovers with his trade’s instruments and asks them what it is that they really want of each other. But this for them is inarticulable: they are unable to say what it is that they want. When he offers, however, to meld them together into a single being which even after death would have one rather than two departed souls, they know that this radical and perfect union is precisely what they have wanted all along and precisely what they have been unable to achieve.

Later in the Symposium, the mysterious figure of Diotima tells Socrates that the experience of beauty involves desire toward some transcendent reality (which of course in Plato’s case, is not God as such but rather the divine realm of the Forms); encountering true beauty is thus a gradual ascent to the transcendent, like going up the rungs of a ladder: the beauty of a beautiful person allows one to see the beauty of souls, which allows the perceiver to see the beauty of laws and institutions, and finally to experience full unity with Beauty itself, a participation in the “form” of beauty, which, for Plato, leaves all concrete and particular instantiations of it behind. Beautiful things gradually draw the perceiver (ecstatically) out of herself toward participation in the transcendent. Beauty in Diotima’s vision opens out always onto the more; like our own ordinary experiences of beauty, it is generative and fecund. Indeed, Diotima’s speech connects erotic desire not simply with beauty as such but with something a bit more subtle. “What Love wants,” she says, “is not beauty” but rather “reproduction and birth in beauty” (206E); that is, love wants to make beauty last, to extend the fragile moment to eternity, love wants beauty to go on forever; the implication, of course, is that beauty must be something immortal and infinite. For Plato, real beauty, the divine Form of Beauty, “neither comes to be nor perishes, neither waxes nor wanes . . . it grows neither greater nor less, and is affected by nothing” (211A).

What consolations proceed from this conclusion, especially from the perspective of the sensate world where the fragility of things is perpetually and pellucidly reasserted through aging, decrepitude, sickness, loss, grief, decay, degeneration, deterioration, and, ultimately, death? It is no wonder, then, our poignant experiences of beauty leave us feeling wistful and a bit melancholic. They announce, even well before the Christian era, that this world is not our home; we must always make do with poor substitutes that can only gesture toward the tremendous infinitude of our wanting. Human desire is ultimately for the unlimited and the un-circumscribed, that which does not age or fray or weaken and which can never, ever be removed from us.

Plato’s Phaedrus continues the trope of the eternal forms and the capacity of Beauty in particular to redirect human beings ultimately toward the divine. The title character has become enamored of the somewhat conventional speeches of a certain Lysias, which are proved by Socrates during the course of the dialogue to be unworthy of Phaedrus’s admiration. The ancient Neoplatonic commentator Hermias interpreted Socrates’s intervention not just as a discerning judge of rhetoric but also as a spiritual intervention: “Where are you going? Where have you come from? You’ve abandoned true beauty, the beauty in divine things, and are marveling at the beauty in speeches.” The fundamental problem here is that Phaedrus had lost sight of the divine source of beauty and has been resting content with only a partial manifestation of it. He’s mistaken the part for the whole. Socrates then proceeds with his own set of rival speeches which, among other things, make the connection between Beauty and desire—a transfigured, holy desire—palpably clear.

In his second, more earnest speech, Socrates offers Phaedrus an extended metaphor or allegory of the human soul as a charioteer trying to control two winged horses with two quite different temperaments, one being good and noble and the other unruly and insolent. Once upon a time, the winged soul had flown with the gods, “gazing upwards at what is Reality itself” (249), but repeated exposures to ugliness, evil and habitual capitulations to one’s own baser passions have led not only to the breaking off of its wings but, more tragically, to a dimmed memory that it ever had the ability to fly at all. On Plato’s telling, inferior copies of justice or wisdom that human beings encounter in the world are too weak to remind us of our divine origins. Only encounters with beauty are powerful and radiant enough to jog our memories of this once-elevated state: “When a man sees beauty in this world and has a remembrance of true beauty, he begins to grow wings” (249). Beauty, as one modern philosopher has written, is thus a call “of the origin back to the origin, the call of what is first back to what is first, can only be a re-call, insofar as the soul is called to remember an intelligible beauty that it has always already witnessed in an absolute past. . . . To see beauty is to see it again, to go toward it is to go back to it” (Chrétien, 10).

Note too that this process of regrowth is the site of no small amount of pain, “pricking” and “wounding” the soul which is “goaded into anguish” until reoriented properly to its fundamentally infinite horizon. A few centuries after Plato, Plotinus wrote a treatise on beauty in the Enneads which describes similar associations of eros with Beauty such that beauty is the cause of love and describes the same sort of blissful pain we have already acknowledged within the context of our own ordinary experience. Plotinus deploys the language of “astonishment, and a sweet shock, and longing, and erotic thrill, and a feeling of being overwhelmed with pleasure” (Plotinus, Enneads III, VI).

Joseph Ratzinger’s 2002 address, “The Feeling of Things, the Contemplation of Beauty,” refers directly to this theme of the woundedness of beauty from the Phaedrus, but transforms it christologically. In profound experiences of beauty (he relates the story of being overcome while listening to a Bach cantata) it is the beauty of the wounded Christ who pricks our hearts. On a Christian view, then, to see beauty is not simply to see (as Stratford Caldecott has said beautifully) “a distant world of Platonic archetypes, but the Archetype of archetypes wedded to the world, and allowing itself to be crushed by the world in order to transform it” (34). In other words, what Christianity brought to the discourse of Beauty was precisely the downward descent of divine love and desire for us in the Incarnation of our Lord Jesus Christ. "For God so loved the world that he gave his only begotten son" (John 3:16).

It was the mysteriously named Pseudo-Dionysius who being intimately familiar with Plato as well as Neoplatonists like Plotinus and Proclus appropriated the thought of these philosophical forebears in a decisively Christian key, specifically by introducing to them the movement of divine descent down to human beings, not just human ascent up to God. He understood Beauty not as existing in the impersonal world of the Forms but rather as another name of the personal God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, the one who, “out of love . . . has come down to be at our level of nature and has become a being. He, the transcendent God, has taken on the name of man” (DN II.10).[1]

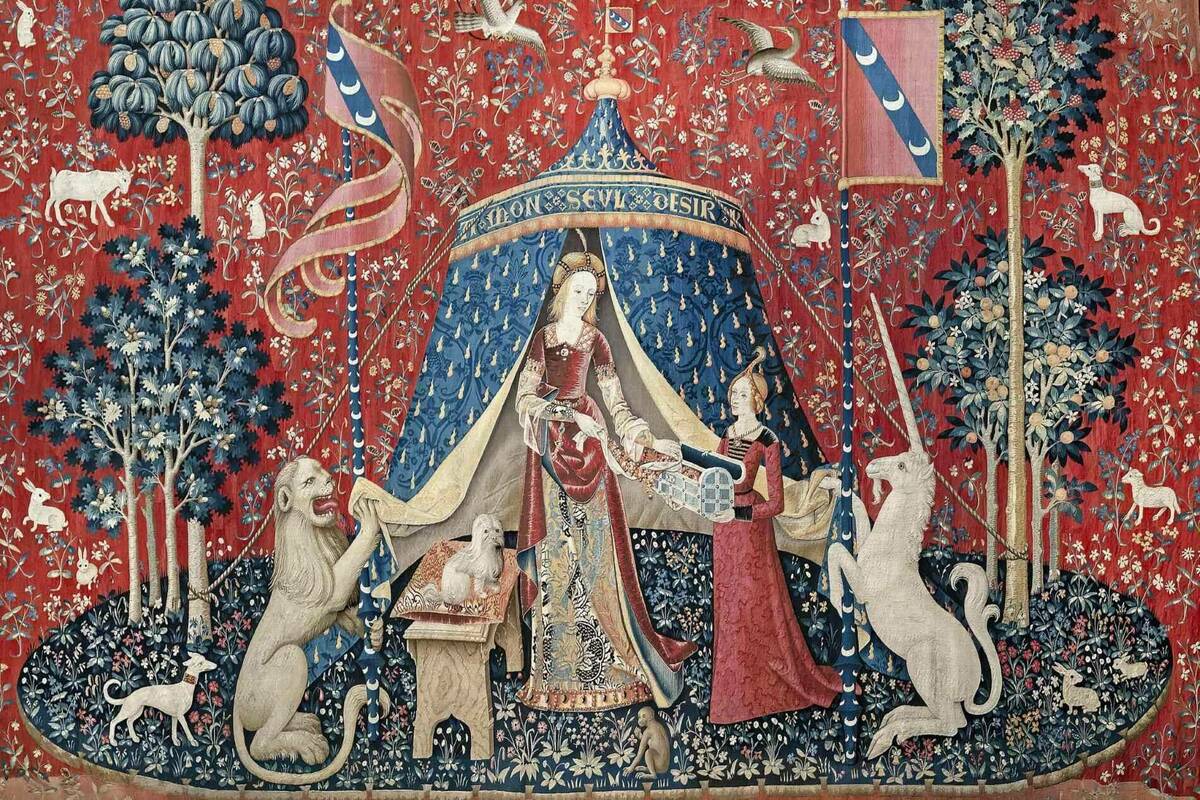

For Pseudo-Dionysius, “Beauty” is hand in glove with the name “Goodness,” where the Good is understood to be luminously self-diffusive and deeply generous, extending into all existing things and calling every scattered thing back to union with itself (DN 4.4). For Pseudo-Dionysius, the beautiful is “therefore the same as the Good, for everything looks to the Beautiful and the Good as the cause of being, and there is nothing in the world without a share of the Beautiful and the Good” (DN 4.7). Furthermore, the Beautiful and the Good are simultaneously the objects and the cause of universal desire: “All things must desire, must yearn for, must love, the Beautiful and the Good” (DN 4.10); “Beauty ‘bids’ all things to itself (whence it is called ‘beauty’) and gathers everything into itself” (DN 4.7). It is the “Goal,” the “Beloved,” and the “Cause” toward which all things move, since it is the longing for beauty which actually brings them into being” (DN 4.7).

The implication is that every experience of beauty is situated in and conditioned by the context of what turns out to be an infinite desire for God. What is interesting to me here, though, is that in the Christian tradition, this desire is not ours alone, but is anticipated by God’s prior desire for us. To say that God is Good in the tradition is to say that God is superabundantly generous; God holds and sustains all things in existence. As Pseudo-Dionysius put it, the “very cause of the universe in the beautiful, good superabundance of his benign yearning for all is also carried outside of himself in the loving care he has for everything” (DN 4.7). God, we can surmise, might well also take on the name of Desiring Beauty.

Let us take a moment to let what Pseudo-Dionysius is saying really land. My sunflower patch and Dostoevsky novels and Terrance Malick’s films make me feel a sense of longing not only out of lack, not only because this side of heaven I am not fully united with the God who is divine Beauty, but also because I am always-already desired by the God who is Desiring Beauty, who loves me in all my particularity out of an extraordinary fullness and plenitude. With Hopkins again we can say: “Give beauty back, beauty, beauty, beauty, back to God, beauty’s self and beauty’s giver.” Our giving beauty back in the form of desire mirrors and participates in God’s prior gift of beauty—God’s very gift of God’s Self—to us. When I respond to beauty with love, I am participating in the infinite generosity of a God who calls me into existence to say lovingly to me and to every seed and to every petal: it is good that you exist.[2]

These ideas—at least a partial identity between Goodness and Beauty, the notion of goodness as generous and self-diffusive, and the connection between goodness and desire—reappear with characteristic force and clarity in Thomas Aquinas (he cites Pseudo-Dionysius over 600 times in the Summa Theologiae alone and wrote a significant commentary on his The Divine Names). If the Good is “that which all things desire, and since this has the aspect of an end, it is clear that goodness implies the aspect of an end” (telos) (ST I q.5, a.4). Thus, thinking about “the Good” includes thinking about what a thing’s final purpose or meaning or end is. For Aquinas, the “end” of a human being is “the uncreated good, namely, God, Who alone by His infinite goodness can perfectly satisfy man’s will” (ST I-II q.3. a.1). It is no wonder, then, that our experiences of beauty feel (and are!) real but—if they are asked to stand alone or exist only in human subjectivity or the realm of personal aesthetic taste—can at worst be counterfeit and at best only gestural.

Can we come to learn to see the giftedness of all things with the proper sense of wonder? Can we be habituated to look at the beauty shining all around us—and the delightful longing that it provokes in us—as a testimony to and reflection of God’s infinite desire for us? What else does beauty say to us except that we are supernatural creatures with a transcendent vocation destined for glory—perhaps even for sainthood!—creatures whose every natural, provisional desire for goods reveals an ever more fundamental desire for the supreme Good whose infinite desire for us has no equal? How shall we then live?

Editorial Note: An earlier version of this lecture (“On Beauty, the ‘Forgotten Transcendental’”) was presented at the University of St. Thomas for the inaugural event of the Claritas Initiative in September of 2023, and this version (edited and shortened for publication) was delivered for a “town and gown” event at the University of St. Andrews on November 15, 2023, on the eve of the feast of Saint Margaret of Scotland.

[1] It is worth noting that exactly as in Diotima’s speech of Plato’s Symposium which lays out the theory of the Forms, the form of Beauty in Pseudo-Dionysius is “forever so, unvaryingly, unchangeably so, beautiful but not as something coming to birth and death, to growth or decay, not lovely in one respect while ugly in some other way. It is not beautiful ‘now’ but otherwise ‘then,’ beautiful in relation to one thing but not to another. It is not beautiful in one place and not so in another, as though it could be beautiful for some and not for others. Ah no! In itself and by itself it is the uniquely and the eternally beautiful” (DN 4.7).

[2] D.C. Schindler is quite fond of quoting this line from Josef Pieper’s Faith-Hope-Love (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1997) across work that has been extraordinarily formative for my own thinking.