SPOILER ALERT: SPOILERS AHEAD!

Blessed art thou among women

and blessed is the fruit of thy womb . . .

The doctrine of the Theotokos’s perpetual virginity is, paradoxically, a celebration of Mary’s utter fecundity. Surrendering utterly to the will of God, Mary bears fruit completely and comprehensively, in one elegant gesture of incarnation, in the Word himself. All of our human effort, all our worthwhile striving to produce, remain asymptotic reaches towards Mary’s fiat, in which she reaches the limit of human availability to do the will of God and produces maximal results: God himself.

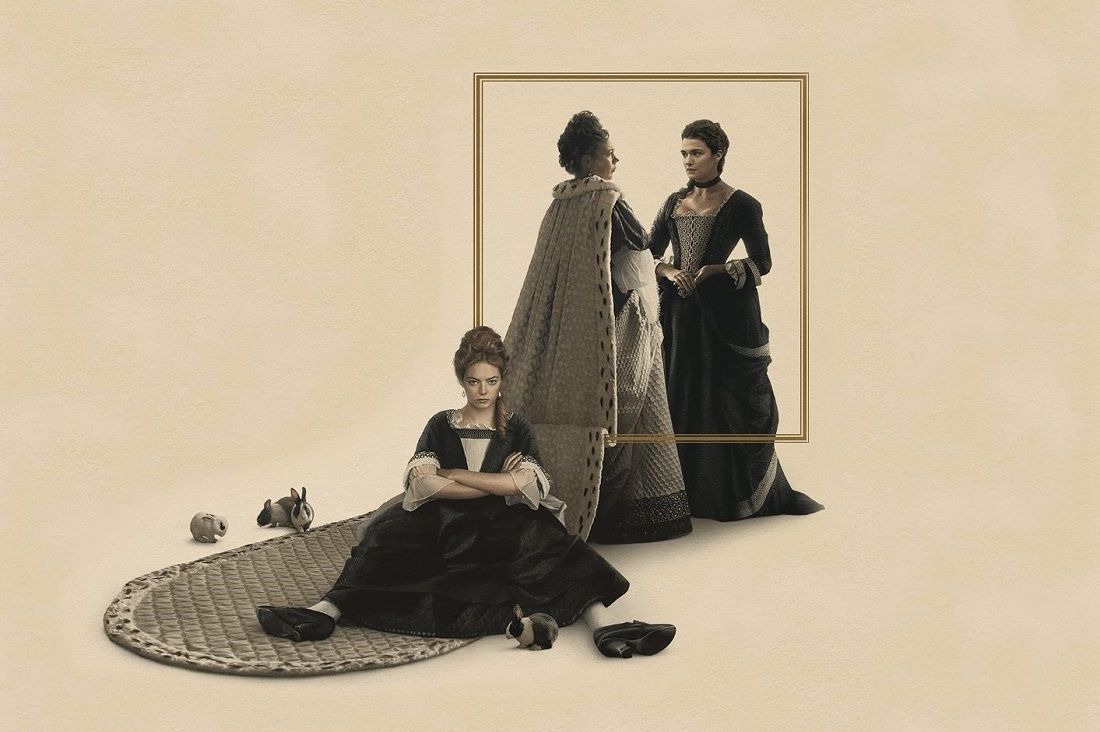

Queen Anne, the broken heart of Yorgos Lanthimos’s mournful farce The Favourite, is a woman who is certainly fecund but whose efforts to bear fruit culminate in unrelentingly repeated traumas of loss. Seventeen rabbits hop around her room as insultingly ambulant tombstones for each of the fruits of her womb whom she has lost. The animal emblem for abundant procreation becomes a grotesquely fluffy incarnation of death. Anne, whose husband, children, and beloved sister have all been taken from her, becomes a fragile monument to loss.

The plot is simple: Sarah Churchill (ancestor of the great Winston), Anne’s childhood friend, and Sarah’s impoverished cousin—Abigail, a newcomer to the court—war for Anne’s favor and the accompanying benefits: security, status, and survival. Let the games begin.

The Favourite is certainly not a period piece in the sense of attempting to recapture a previous era; the film is less interested in the unnamed War of Spanish Succession, which serves as a set piece, and more interested in the frantic battle of its heroines against the swelling tides of loss in the zero-sum game of court favor.

In keeping with the rest of Lanthimos’s English-language oeuvre—The Lobster (2015) and The Killing of a Sacred Deer (2017)—The Favourite rolls out the trappings of a particular genre until slowly boiling down these staple elements into a singular cry of wry despair. The court of Queen Anne, twisted through Robbie Ryan’s fish-eye lens, is not the escapist fantasy of a period piece—a retreat to a different time—rather it resembles the reality we go to the movies to forget. We the viewers are immured in the same nightmarish dynamics of bootless living like the men and women we see on screen.

Loss is the deepest reality of Lanthimos’s cinematic universe. Death and taxes are twin manifestations of the ultimate certainty: for she who has, even if she has little, it will be taken away.

Lanthimos decides to concretize the speculative murmurs of a romance between life-long friends Sarah Churchill and Queen Anne in his film, partially—one can safely assume—to secure the sure profits (monetary and artistic) reaped by sex on screen. But movies spin their stories through images—bodies in movement—rather than written word. Thus, the sexual intrigue surrounding Anne creates a potent, visceral representation of Anne’s deep yearning for affirmation, for love, for her attempts to bear fruit in relationship. Anne’s frustrated loneliness and her efforts to fill that lonely void are the gale force winds that fill the film’s sails. The sexual intrigue between the three protagonists also illustrates the lengths to which Sarah and Abigail will go: their absolute giving over of their bodies and souls to the project of securing status and survival. All three women use sex to escape from the (inescapable) reality of loss.

After being drugged by Abigail, sent on a death ride, dragged by her horse through the woods and picked up by enterprising peasants who sell her to a whorehouse, Sarah, bedraggled and bruised, appears back in Anne’s palace boudoir like a poltergeist who cannot be exorcised. Where has she been? Hell, she intones in a tomblike voice.

The Sarahs of this world will always harrow themselves out of these wastelands of misery where hoi polloi dwell, by leveraging their wealth and status to catapult themselves back to their proper place on top. The Abigails of the world will always be fighting tooth and nail to claw themselves out of the living hells of their scrappy lives as bottom-dwellers. The only world that has, does, and will exist is this rigged competition to survive that finally ceases in the fatal draw of death.

Sarah’s and Abigail’s death-match takes place against the milieu of Queen Anne’s bunnies hopping across the screen: a constant reminder of where the efforts of nature and human lives will ultimately end—the grave.

In Lanthimos’s farce, death is the final punchline, the sick joke that renders Abigail’s desperate scrambles for survival, Sarah’s all-consuming pursuit of power, and Anne’s search for love bleakly laughable. All the business of queens and kitchen maids will finally resolve itself into the final equity of death. For the fruit of all our wombs—all of our efforts, our human toil—is death, “a necessary end.”

It really is death (or bunnies) all the way down.

Underneath the closing credits, Elton John’s Skyline Pigeon plays. After bathing its viewers in the richly costumed cinematic nihilism, The Favourite closes with a secular hymn to transcendence, yearning for freedom.

After proving the absolute impossibility of escape from the caged world of laughably fruitless fighting for survival in the face of inevitable death, Lanthimos’s film, like the eponymous pigeon, dreams of escape into the open air.

But how?

If there is no possibility of meaning in the face of death, then Abigail, Sarah, Anne, and we the viewers are trapped forever in the cages of seeking our own self-interest, competing against others for our right to survive for what little time we have in the miserable world we are left with. The denouement of their lives—and ours—is loss.

If there is a reality deeper than loss—if there is a possibility of our lives bearing fruit into a life and love that can triumph over the defeat of death—then perhaps there is a meaning and a goodness to which the self can surrender. For surrender is an exit from the competition; it is not winning, but rather accepting loss for the sake of a greater good which can be achieved on the other side of defeat.

In the fight of the self against loss, surrender could be the key that “opens out this cage towards the sun.”

But how does the self surrender?

. . . Blessed art thou among women

and blessed is the fruit of thy womb

Editorial Statement: In anticipation of the 91st Academy Awards on February 24, we present a series (click here) exploring the philosophical and theological elements in each of the eight films nominated for Best Picture. We hope to convey through this series that, awards politics and Hollywood scandals aside, films are an art form, and art matters to the Christian life. It allows us to locate the narratives we see onscreen—along with the narratives of our own lives—within the context of the narrative of salvation history, of God's love poured forth in the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ.

Featured Image: Screen Capture of The Favourite Official Website, Fair Use.