In addition, a readiness to discard others finds expression in vicious attitudes that we thought long past, such as racism, which retreats underground only to keep reemerging. Instances of racism continue to shame us, for they show that our supposed social progress is not as real or definitive as we think.

—Pope Francis, Fratelli Tutti

Shaun Blanchard: Let us start with something encouraging and hopeful: You noted recently, in a Rome Reports interview, that since the murder of George Floyd you have seen more openness from Catholics on the issue of racism than any other time in your life. Can you talk some about that?

Fr. Joshua Johnson: After the murders of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor and George Floyd, I was invited to have a dialogue on race with my friend, Father Mike Schmitz, on the Ascension Press YouTube channel. A number of Catholics tuned into our conversation, listened to our discussion, and learned about practical steps they could take to work towards racial reconciliation.

One of the themes from our conversation that resonated most with white Catholics was learning about spiritual acts of reparation. The word reparation literally means “to make it right.” In the Bible, after Zaccheaus encountered the love of Jesus, he was not reconciled to his community until he “made it right” by paying back what he took from them four times over. Like Zaccheaus, many Catholics desire to have racial reconciliation in the United States of America.

However, reconciliation must be preceded by reparation. In the Bible, Ezra and Daniel made reparation by offering prayers and penances for their sins, the sins of other people, and the sins of their ancestors who passed away. Intentionally offering up Masses of reparation, Holy Hours before the Blessed Sacrament, Divine Mercy Chaplets, Rosaries and days of fasting as a penance for personal sins and communal sins seemed to really resonate with our Catholic audience.

SB: It sounds like one of the big takeaways from the people reaching out to you is that they are recognizing racism for the first time as a theological and spiritual problem.

JJ: Yes.

SB: It is the way that a lot of devout Catholics instinctively would think of attacks on the family or abortion or even war or something like that as having spiritual forces behind it. And I think that there are resources in the Catholic tradition for doing this. You know, to call Nazi ideology “demonic”—I think Pius XI used language like that in his encyclical (Mitt brennender Sorge, 1937).

But for whatever reason, a lot of white American Catholics, myself included, have been slow to apply that strength of language to our own country's history and our own country's present. And I wonder if, in my own case, I have struggled to really wrap my head around how evil the systems of government and culture that I come from, and that I hold dear and that my ancestors were a part of, really are. It's hard to really look at that in the mirror.

JJ: Yes, because now we are looking at our own family lineage. Some of our families participated in sinful structures that oppressed entire groups of people because of the color of their skin. However, we must always remember that the same God who loves us also loves our ancestors who may have participated in grave sins against Black men and women made in the image of God.

God’s love for us should inspire all of us to work together for reconciliation. As a Church, we have not adequately addressed the evils of racism. It is our responsibility as disciples of Jesus, to take on the sins of others and offer penances. This is what I do every day as a Catholic priest when I sit in the Confessional.

A person comes to the Sacrament of Reconciliation, confesses their sins, recites their act of contrition, receives absolution, and commits to doing a penance. After the person leaves the confessional, I, the priest, also commit to doing a penance for the repentant sinner. To be clear, I did not commit that person’s sins. But, as a member of the body of Christ, I must make up for what is lacking in the members of the body of Christ.

As baptized Christians, we are all connected. For instance, in 2019, I began to offer Masses and Eucharistic Holy Hours of Reparation for the sins of all the priests who have sexually abused men, women, and children. In my history, I have never sexually abused another person. But, as a member of the body of Christ, I took on a number of penances in reparation for the sins of the clergy. I also offered free counseling to people who were sexually abused by priests. In addition to these actions, I publicly spoke out against the bishops who participated in these terrible crimes. Again, I provided counseling, called for reform, offered penances, and made reparation to God on behalf of other people because that is an essential part of discipleship.

SB: It really should not be too hard for a Catholic to understand the concept of communal guilt: biblically, sacramentally, and in our understanding of the communion of saints. It is interesting that we instinctively get this in certain contexts (we meaning white Catholics), but we might fight against it when it is about . . .

JJ: Racism.

SB: Issues that are a little more uncomfortable, like racism.

JJ: Yes, every year on Ash Wednesday we read in the Bible these words: “Repent and believe in the Gospel.” The Greek word for repent is metanoia. Most of us translate metanoia to mean changing one’s way of life. This definition is certainly true, but incomplete. For thousands of years, the Church also understood this word to mean, “do penance,” in addition to changing one’s life.

And like every priest who goes to confession and hears confessions, we are all invited to do penances not only for our personal sins, but also for the sins of other people in our community, including our dead ancestors. This is a biblical concept that is not being taught in our Churches. Remember, when Ezra, Nehemiah and Daniel repented in the Old Testament, it was not just for their sins. It was also for . . .

SB: Yes, the people.

JJ: You got it. They repented for their sins and the sins of their ancestors. In the Scriptures, Daniel prayed, “To us, O Lord, belongs confusion of face, to our kings, to our princes, and to our fathers, because we have sinned against you” (Dn 9:8). Daniel wanted for all of his people to be reconciled with God so he prayed on their behalf.

If we want sinners to be reconciled back to God and abide in communion with other members of the body of Christ, then we must do penances on their behalf. We clearly understand this truth when it comes to praying and fasting for the conversion of our children, siblings, or spouses. How many parents spend hours on their knees, day and night, offering up Divine Mercy Chaplets and Rosaries for their loved ones who may be in Purgatory or who are currently not living a sacramental life? Do we believe that our penances of prayers and fasting can be used by God to bring about the conversion of our loved ones?

If yes, then I want to propose that Catholics should be offering penances for the sins our American ancestors who participated in slavery, racial terrorism, lynchings and Jim Crow Laws. I also propose that we should be offering penances for the conversion of the minds and hearts of the men and women who still support racist practices and policies in the twenty-first century. Unfortunately, some Catholics are not willing to invest in these acts of spiritual reparation because they are what is often referred to as “cafeteria Catholics.” Rather than embracing all of the demands of discipleship, they will pick and choose when they are going to be intentional disciples of Jesus Christ.

SB: That is a good definition of cafeteria Catholicism. So, I wanted to talk about how we narrate American Catholic history. One predominant narrative is a story of various immigrant groups overcoming persecution and poverty to become fully American and thrive institutionally and spiritually. So, the idea is kind of the rags of the potato famine to the election of JFK.

JJ: Yes.

SB: And often this narrative pays a lot of attention to the dynamics and tensions of Irish, German, Italian and Polish immigration, but does not have a ton to say about Black Catholics or Latino Catholics. It is typically noted in this narrative that the KKK also targeted Catholics and Catholics also participated in the Civil Rights movement.

JJ: Some did.

SB: Oh yes, of course. I am thinking of those classic images of Father Hesburgh marching with MLK. While this stuff should be celebrated, it was sad for me to realize that when you honestly dig into the historical record, you see a very ambivalent picture. A lot of Catholics resisted racial integration. In general, the Catholic Church, in my reading, basically reflected the prevailing cultural attitudes on race.

Even Pope Gregory XVI’s great encyclical against the slave trade in 1839 (In supremo apostolatus), was interpreted in a far more restricted manner by southern white Catholics, including bishops, then by northern ones. And this letter, also celebrated by some Catholic apologists, does not actually call for Catholic slaveholders to free their slaves. So, how can we narrate the history of Catholicism in America in a way that recognizes and celebrates Catholic struggles and achievements, but is also honest about institutional Catholic complicity in building and perpetuating the racist structures that are still with us today?

JJ: Historically speaking, the United States of America was founded upon the slaughter of hundreds of indigenous peoples. The Native Americans were already occupying the land now known as Jamestown when the British settled in, overtaking the land previously held by Native Americans. With this came the Euro-American slave trade which transported kidnapped Africans and sold them to Europeans who then brought them to America to provide free labor. Our country was built upon the free labor of African peoples through the institution of slavery. These Black people did not come to America by choice and they were enslaved for hundreds of years. During their enslavement, their families were separated and they were sexually abused, tortured, and killed.

Unfortunately, many Catholic bishops, priests, religious, and laity participated in this grave sin of slavery. Leaders in the Catholic church owned slaves. In fact, America’s first Catholic bishop owned slaves. Has any bishop ever offered a Mass of Reparation for the sins of John Carroll, the first bishop of America?

The Jesuits built Georgetown University through the work of slaves, who, then, were separated from their families and sent to different places in our nation.

SB: Many of them were sent here to Louisiana, right?

JJ: Correct, a lot of them came to Louisiana and many of the descendants of the Georgetown slaves are still here in Louisiana. This is a history that we need to acknowledge. I do not understand how we can look at what the Nazis did to Jewish people during the Holocaust as an evil, but, when some Catholics talk about slavery, they claim it was not as bad as what the Nazis did to the Jews. At the end of the day, what the Nazis did to the Jews was a serious sin and what white Americans did to Black people during slavery and the years that followed was also a grave evil.

A year ago I had the privilege of participating in a pilgrimage to Poland. I visited shrines dedicated to Saint Maximilian Kolbe, Saint John Paul II, and Blessed Jerzy Popieluszko. In addition to these places of prayer, I also spent time in the concentration camps where many Catholics and Jews were murdered by the Nazis. It is interesting how many Catholics are appalled by the inhumane torture the victims of the Holocaust experienced.

No Catholic in their right mind would ever think it could be appropriate to host a party or a wedding at one of the concentration camps. However, how often do Catholics spend time on plantations at parties or weddings, without ever praying for the souls of the Black men and women who were tortured, molested, beaten, and killed on the grounds of these slave labor camps? Unlike the concentration camps, most plantations do not even acknowledge the crimes against humanity committed on their grounds, with the exception of a few, like Whitney Plantation in Edgard, Louisiana.

Now, back to our American history . . . For hundreds of years, slavery was the law of the land. It was a written rule that accommodated white people and discriminated against Black people. After over 200 years of slavery, the Reconstruction period began in America. During this time, racial terrorism continued to happen against Black people through public lynchings and unjust sentences to prisons for no other reason than because of the color of their skin. Literally, there were laws that were created specifically to imprison the free men and women of color.

SB: The system was peonage? There was some formal system.

JJ: Yes, during the Reconstruction period Black people were penalized if they left a job or did not have a job.

SB: If you violate the new laws, you become a kind of slave again—permanently through incarceration.

JJ: Yes, and then, of course, Jim Crow laws were established in this country. The Jim Crow Laws made it illegal for Blacks and whites to work, play, eat, learn and live in the same places. Many Catholics supported Jim Crow laws. They supported the separation of Blacks and whites. They did not want Blacks and whites to be integrated. In the 1960s, the Civil Rights Act happened and even though direct racism seemed to come to an end, the white people who had power perpetuated institutional racism indirectly through practices, unwritten rules and policies, and through written rules that continued to accommodate and give access to white people and discriminate and alienate Black people.

When we examine our American history over the past 400 years, we realize that one of the reasons our country has so few canonized saints is because many of our Catholic clergy, religious and laity betrayed Jesus Christ through their participation in the grave sin of racism. Betraying Jesus is nothing new when it comes to the leaders of his Church. In the beginning, Jesus chose 12 men to be his first apostles. Judas betrayed Jesus, Peter denied Jesus, Thomas doubted Jesus, and the rest of the Apostles abandoned Jesus when he needed them the most. Corruption in the Catholic Church is nothing new. What is unique about American Catholicism though, is the fact that this history of corrupt bishops, priests, religious sisters and brothers, and laity is often not taught in our primary schools, high schools, colleges or seminaries.

One question I hear quite a bit from people is this: “Why are there so few Black Catholics in America?” My response has always been, “How are there so many? How are there so many African-American bishops? How are there so many African American Priests? How are there so many African American Religious Sisters? How are there so many African American laity?”

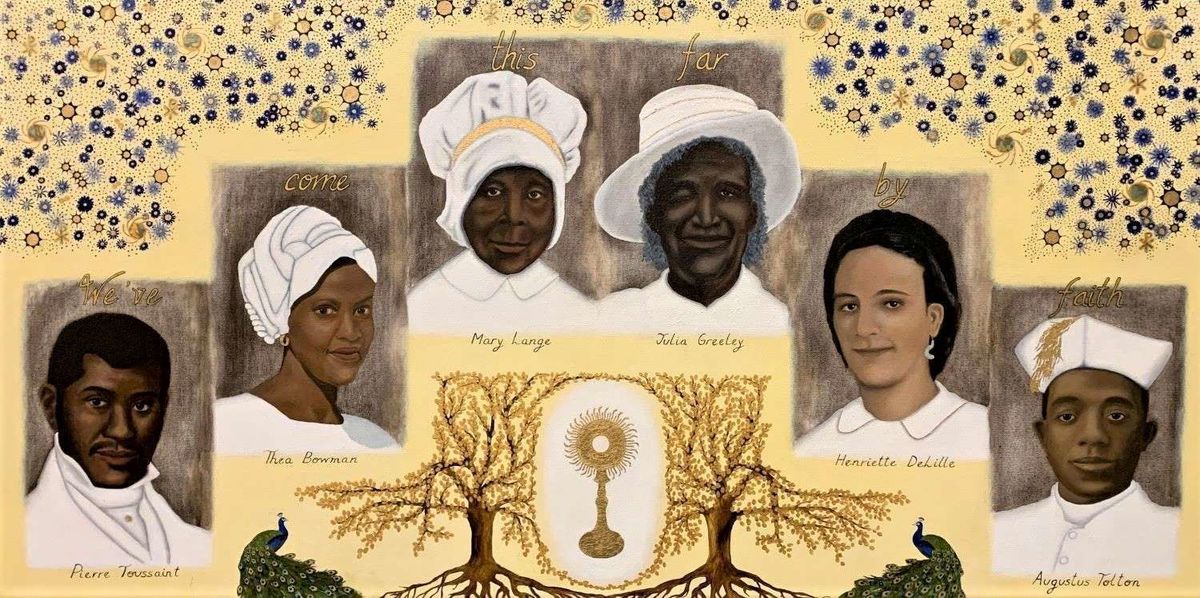

Right now there are six African-Americans on the path to becoming canonized saints. One of the six is Venerable Augustus Tolton. This man was born into slavery and became our country’s first recognized Black priest. He was made a disciple by a holy white priest who invested in him and nurtured his calling to become a priest. However, this priest was not the norm. Most white priests during the time of Venerable Augustus Tolton treated Black people as less than human.

When Augustus attempted to discern the priesthood, he was denied access into every seminary in the United States of America. In order to discern his vocation, he had to receive seminary formation in Europe. Eventually, he was ordained in Rome and then sent back to minister as a Catholic priest in the United States of America. Upon his return home, many of his brother priests called him the N-word and told their parishioners that it was a sin for them to worship with Father Augustus Tolton at Mass.

Another African American on the path to sainthood is Venerable Henriette Delille, the foundress of the Sisters of the Holy Family. Like Venerable Augustus Tolton, she also perceived God inviting her to discern a religious vocation. Unfortunately, she was rejected by many orders including the Ursulines and the Carmelites because she identified as a Black woman. After being rejected by exclusively white orders of nuns, she attempted to co-found an interracial religious community of sisters. However, once again, her dreams were shattered when the leadership in the Church would not accept her proposal.

Finally, on the feast day of St. Teresa of Avila, she professed her vows to her bishop as a religious sister through an order she established to serve the people of color in her community. St. Teresa of Avila founded the discalced Carmelites for a number of reasons but one of them that is often not spoken about is because the old Carmelite order in Spain had a written rule that excluded women who came from Jewish or Moorish blood from entering their community. Her sisters did not know at the time but St. Teresa had Jewish blood in her family lineage. Hence, Mother Henriette Delille also founded a community that was different from all of the religious orders she tried to enter in the past because her sisters would not be discriminated against because of their Black lineage.

The persecution that Black people experienced in the Catholic Church in the nineteenth century continued into the twentieth century. In the 1950s, Archbishop Joseph Rummel, in New Orleans, Louisiana, began to work towards integration in the Archdiocese of New Orleans Catholic School system. During this time he was protested against by clergy, religious, and laity. Men and women who went through seminary formation and participated in the Sacraments on a consistent basis vehemently opposed his leadership.

SB: The Bishop of Raleigh, North Carolina, which was my home diocese, was hit in the head with a rock coming out of Mass when he announced that the schools would be integrated.

JJ: Right? By Catholics?

SB: Presumably.

JJ: In addition to the burning of crosses and protests against Archbishop Rummel, many of the schools barely responded to his invitation to integrate their campuses. However, one school that did respond with generosity to his plans for integration was St. Joseph’s Academy in New Orleans which was run by the Sisters of St. Joseph. Unlike many of the other Catholic Schools in the Archdiocese who only accepted a few Black children, they opened wide the doors of the campus to any Black student who wanted to enroll in their school.

Unfortunately, when they did this many white parents transferred their children to the other Catholic schools that only admitted a few Black children to their campuses. The Sisters of St. Joseph encouraged the other Catholic schools to join them in welcoming children from all different backgrounds to receive a Catholic education but their plea was not accepted. Eventually, they had to shut their school down because so many of their white students left their institution for more segregated Catholic schools.

In the twenty-first century there are still practicing Catholics who continue to perpetuate the racial divide through their participation in racist institutions. For instance, there is a swimming pool in Vacherie, Louisiana that is still segregated in their membership! This is the year 2020 and they are still segregated. Most of the members of this pool are practicing Catholics and many of the people who founded this segregated swimming pool were Catholics.

The way they are able to get away with this racist organization is through their unwritten rule of not accepting Black memberships. Any person can apply for membership and Black people have applied, however, the only people who have ever been accepted into this club are white people. This is the same way some of our fraternities and sororities operate. They do not have a written rule that states Black applicants will not be accepted but it is their practice. Hence, although they will allow a Black person to go through their application process, they will not accept them. This is also the way that many Mardi Gras balls operate.

In 2006, Archbishop Alfred Hughes of New Orleans, Louisiana, addressed racist practices that were operative and hurting people of color in his community. He invited Black Catholics to sit at the table with him because he noticed that many of them were leaving the church. He listened to their stories and found out that many of their parishes were hosting events at a Metairie country club. At that time, in the early 2000s, the country club had a practice that denied Black people access to become members. To address this evil, he wrote a pastoral letter against racism, saying that all Catholic entities must refrain from holding meetings and/or events in clubs or establishments which are not open to a racially and culturally diverse membership.

After this, the Metairie country club began to lose money so they changed their practice and began to allow Black people into their organization as members. Archbishop Hughes’s leadership spoke volumes to Black Catholics in the Archdiocese of New Orleans. His actions showed people of color that we are all necessary members of the body of Christ. If other Catholics begin to imitate his leadership, by protesting institutions that continue to perpetuate the racial divide through their practices and policies, then we will begin to experience reconciliation in our divided Church and nation. Just like we protest against abortion, we should also protest against organizations that discriminate against Black and brown people on the basis of the color of their skin.

SB: It seems that a lot of white Catholics would be in favor of serving people of color through mission trips to other countries. In theory, they have this kind of global diverse view of what it means to be Catholic. But, in practice, they have an attitude, maybe ranging from patronizing all the way to hateful, wherever they fall on the spectrum specifically towards African Americans. So, what I've been wondering lately is to what extent is the problem a cultural issue for Americans? It is clearly race-based, but it is also an animus specifically against the people that live on the other side of town.

JJ; There are some white Catholics who are seriously striving to be intentional disciples of Jesus Christ. They are doing their best to make disciples of all nations. Disciples are formed through authentic friendships that foster deeper encounters with Christ in the scriptures and sacraments. These necessary friendships are fostered through proximity. Unfortunately, a number of white Catholics in the United States of America, including our bishops, priests, religious sisters and brothers and lay leaders have chosen to not be proximate to the people of color in this nation.

Some of our clergy, religious and lay leaders in the American Catholic Church have spent hundreds and thousands of dollars to travel hundreds and thousands of miles all over the world to share the gospel with people from other nations. This is good and true and beautiful. However, in many cases, these same Catholics who spend so much of their money to spend two weeks in a third world country, do not even share the joy of the gospel with the people of color who live in the geographical boundaries of their parish communities.

I think one of the reasons why some white Catholics fear getting proximate to the people of color who live in the geographical boundaries of their parish communities is because they may hear stories from their Black and Brown brothers and sisters that might change the way they understand reality.

SB: Do you think this might have something to do with the classic white American Catholic narrative about our own history in America? Specifically, the narrative that we overcame the persecution of the Protestant establishment, proved we could be good Americans, fought in the Second World War, built our parishes and overcame adversity because we were good citizens and hard-working people.

JJ: Yes.

SB: Something I have heard you talk about before is how the poor and middle-class white Catholics benefited from the Homestead Act.

JJ: Indeed, in 1862, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Homestead Act which granted land to white and Black farmers. Then, when Andrew Johnson became the President of the United States he rescinded the order that promised Black farmers land that was confiscated from the Confederates. Hence, many white Americans were given large numbers of acres of land for free and many African Americans received nothing.

The government literally gave land away to white Americans and with land comes opportunity, power and generational wealth. Black people on the other hand continued to work the land, but did not own the land that was promised to them. This country was built on the free labor of Black men and women. Sadly, many of them never benefited from the free work they put into this country.

Now, when some white Catholics hear the truth about the Homestead Act, they begin to see their family history a little different. Their family wealth and prosperity wasn’t something their ancestors fought hard for or earned. Rather, it was promised to Black people and given to white people.

There is just so much truth about our history that we will not know unless we get out of our comfort zones and lean into intentional relationships with people of different ethnicities and tongues.

For instance, many years ago, I did missionary work in Juarez, Mexico. I worked on the border of El Paso, Texas and Juarez, Mexico. I ministered to some of the poorest of the poor on the border. Prior to this mission immersion I had very little contact with people of Mexican descent. The majority of what I heard about undocumented immigrants came from news outlets and the media. I knew nothing of their circumstances and sufferings until I lived with these people who were made in the image of God. It was not until I was close to them, worshiped God at Mass with them, listened to their stories, prayed for their well-being and shared life with their families that I gained an entirely new perspective on these suffering members of the body of Christ.

This is the model of discipleship in the early Church. At Pentecost, when the Apostles received the Holy Spirit, they left their comfort zone and dwelt with people from other nations and tongues. Until white Catholics intentionally invest in consistent relationships with people of color through Bible studies, prayer groups, service opportunities and friendships, they will not be able to work with people of color in reforming unjust racist practices and policies that continue to perpetuate inequality, inequity, and the racial divide in the United States of America.

Far too often I have heard well-meaning white Catholics approach racism from a place of pride and make statements like this: “I know what the real issue is for Black and Brown people!” or “Let me tell you what their problems are and how they can fix them!” I think a better approach would be the following:

“Holy Spirit, teach me how to fast from speaking. Please help me to listen to my Black and Brown brothers and sisters in the body of Christ so I can learn from them how I can best accompany them and work with them to reform racial injustices in our local Church and nation. Jesus, I trust that nothing will be impossible for You!”

SB: I think there is a spiritual pride that can afflict Catholics. Once they feel like they have been properly catechized, read the right books, prayed their rosaries and participated in daily Mass they can experience a spiritual pride that inoculates them from humility.

JJ: Yes! Even the greatest saints who loved God very much made mistakes in their ministry and did not have the mind of Christ in their thinking or the correct words of Christ in all of their teachings. A perfect example of this is Saint Catherine Laboure. When speaking of the mistaken predictions of Saint Catherine Laboure, Pope Benedict XIV said that the revelations of this canonized saint which were derived from her mystical raptures were filled with errors! This woman loved Jesus Christ! She worshiped God at the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass. She spent hours in prayer every day. She strived to be an obedient daughter of Holy Mother Church. And she was still wrong in her understanding!

If this saint had errors in her way of life then we should all be open to the reality that we may be wrong too in the ways in which we are living out our discipleship of Jesus Christ. This is true for me too! Even though I spend an hour before the Blessed Sacrament, read Sacred Scripture, recite the Rosary, pray the Liturgy of the Hours, worship God at the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass and fast during the week; that does not mean that I still don’t miss the mark and make mistakes in the way that I think, the words that I speak and the choices I make in my work and activity.

SB: It is sad that even in the wake of the George Floyd series of events, a lot of Catholics continue to deny systemic or institutional racism. There seems to be a kind of spiritual blindness.

JJ: That is precisely why I believe there has been a demonic stronghold of racism attacking this nation. This demonic stronghold has existed since the enslavement of Black people hundreds of years ago and it continues to be operative in our present moment through unchecked racist practices and policies.

SB: I wanted to make sure that we explicitly covered the six African Americans on the path to sainthood. I had the chance to attend the Day of Reflection for the six African Americans on the path to sainthood at your wonderful parish in St. Amant. It was a really awesome event with a dynamic lineup of speakers. Can you say something about a couple of these causes? Do you have a particular devotion to any of them? Would you offer a prediction for who the first African American canonized saint will be?

JJ: Each one of the candidates for sainthood: Father Augustus Tolton, Pierre Toussaint, Julia Greely, Sister Thea Bowman, Mother Mary Lange, and Mother Henriette Delille experienced institutional racism and all of them persevered in their relationship with Jesus and the Catholic Church. These candidates for sainthood remained faithful even when members of the body of Christ in the Catholic Church alienated, discriminated and persecuted them. Their fidelity and perseverance is very inspiring for so many people of color in the American Catholic Church.

SB: If you could have dinner with only one of them, who would you choose?

JJ: I would choose Father Augustus Tolton. At one time in our nation’s history, he was the only African American priest. Currently, I am the only African American priest in the Diocese of Baton Rouge. He was supported in his call to the priesthood by a few men and women who were white disciples of Jesus Christ and at the same he was persecuted by multitudes of white men and women in the Catholic Church. I would love to listen to his stories so that I can share them with American Catholics in the twenty-first century. I think his witness can inspire people of color to persevere as necessary members of the body of Christ in the Church and also draw white Catholics to become allies of people of color in the Church today who can potentially be the future saints of tomorrow.

SB: Thank you so much.

JJ: Thank you!

EDITORIAL NOTE: Fr. Josh Johnson is the Director of Vocations for the Diocese of Baton Rouge, Pastor of Our Lady of the Holy Rosary Catholic Church, and the Co-Chair for the Commission in Racial Harmony. He is also the author of several books, including Broken and Blessed: An Invitation to My Generation and is the host of the weekly podcast, Ask Fr. Josh.