Joy and Music

Where there is music there is joy,” says one of the ancient Chinese classics, Li Ki, as rendered by James Legge. A literal translation of the same sentence would be “Music is joy.” In fact, joy and music are represented by one and the same character. When it is intended to denote music, it is pronounced “yueh”; when it is intended to denote joy, it is pronounced “lo.” But the same word is used in both cases. From this you can easily realize how inseparable the spirit of joy is from the spirit of music.

According to the Chinese way of thinking, music is joy, and joy is music, because both of them are essentially bound up with the idea of Harmony. In The Treatise on Music, the origin of music is traced to the harmony of the cosmos. It says:

The breath of earth ascends on high, and the breath of heaven descends below. These in their repressive and expansive powers come into mutual contact, and heaven and earth act on each other. (The susceptibilities of nature) are roused by the thunder, excited by the wind and rain, moved by the four seasons, and warmed by the sun and the moon; and all the processes of change and growth vigorously proceed. Thus it was that music was framed to indicate the harmony between heaven and earth.

In another place, it says, “Great music expresses the harmony of heaven and earth.”

Now, heaven and earth constitute the Macrocosm, while man is Microcosm. If a man achieves a harmony within himself corresponding to the harmony of the Big Cosmos, then the spirit of joy will swell up spontaneously from the depths of his being, indicating that he is one with the Cosmos. In other words, joy comes from the perfect realization of one’s personality, which in turn depends upon the achievement of interior harmony. As music is the art of harmony par excellence, it is little wonder that the ancient Chinese sages laid such emphasis on the cultivation of music as a means of developing the human personality.

Let one example illustrate the point. It is recorded in The Book of History how Emperor Shun appointed his Cabinet, including the Prime Minister and Ministers of Agriculture, Education, Justice, Public Works, and so forth. What interests me particularly is the appointment of the Minister of Music. The Emperor said, “Ku’ei, I appoint you to take charge of music, to teach our sons to be straight- forward and yet mild, to be generous and yet firm, to be strong without being rude, and to be simple without being arrogant.”

Confucius was in the grand tradition when he announced his program for the education of his pupils: “First arouse their interest in learning by means of poetry; then establish their character by making them practice the rules of propriety; finally, harmonize their personality by means of music.” It is only in the last stage that one attains the spirit of joy. As Confucius put it, “To know it is not so good as to like it; and to like it is not so good as to rejoice in it.”

But, just as there are different styles of music, even though all of them are good, so there are different levels or modes of joy. Joy, as understood by the Confucianist sage, was not exactly the same as the joy of the Taoist, and both in turn differed from that of the Buddhist. The only thing in common to the three schools is that their joy is sharply distinct from, and superior to, the sensual pleasures of the world.

The Joy of Confucius

The atmosphere of joy in which Confucius lived begins to radiate in the very first pages of his book of Analects. In fact, it sets the tone of the whole book. These are the opening words:

The Master said, “Is it not a true delight to learn and to practice constantly what one has learned? Is it not a real joy to see men of kindred spirit gathered from distant places? Is it not characteristic of the gentleman not to be saddened even when his qualities are not known by others?”

Here we find the joy of learning, the joy of fellowship, and the joy of the perfect development of one’s personality without regard to recognition by the world. Confucius described himself as “a man who is so eagerly absorbed in learning and teaching as to forget his meals, and who finds such joy in it as to forget all his worries, being quite oblivious of the coming on of old age.”

Among his pupils, the one for whom Confucius had the greatest love was Yen Huei. Indeed the Master never tired of praising him. He said: “How good is Huei! With a single bamboo bowl of rice, and a single ladle of cabbage soup, living in a miserable alley! Others could not have borne such distress, but Huei has never lost his spirit of joy. How good is Huei!” In this bit of praise for his disciple, Confucius showed his admiration for people whose joy comes from within and is not dependent upon the external circumstances of life. In terms of practical life, it may be said the Confucian joy comes from the awareness that one has well acquitted oneself of one’s duties. Tseng-shen, another of the great pupils of Confucius, once said, “Every day I examine myself on three points: In planning for others, have I failed in conscientiousness? In dealing with my friends, have I been wanting in sincerity? In learning, have I neglected to practice what my Master has taught me?”

Yet, great as he was, Tseng-shen was considered much less gifted than Yen Huei. In fact, Confucius referred to Tseng-shen as “stupid,” presumably because the latter had to interpret joy for himself in terms of particular individual actions, whereas Yen Huei seemed to rise above these small details.

Stupid or not as he might have been in the mind of the Master, Tseng-shen has been the model whom most later Confucian scholars have patterned their lives upon; the simple reason for this is that Yen Huei was inimitable. Only the more gifted ones have dared to aspire to Yen Huei’s level of joy, and, to my knowledge, none has ever quite reached it. His was indeed a true greatness, described by Tseng-shen in these words: “Clever, yet not ashamed to consult those less clever than himself; widely gifted, yet not ashamed to consult those with few gifts; having, yet seeming not to have; full, yet seeming empty; offended against, yet never reckoning.”

Yet, in spite of the intellectual quality of his notion of joy, Confucius did not believe it necessary to reject the small good things and the comforts of life. He only counseled moderation in our enjoyment of them. His teaching on moderation is well illustrated in “The Song of the Cricket.” This composition was written in a sort of antiphonal style, the alternate verses to be sung by a group of feasters and a “moderator.” It goes like this:

THE SONG OF THE CRICKET

The Feasters:

The cricket sings in the hall,

The year is late in the fall.

Let’s dance and sing today;

The sun and the moon wouldn’t stay.The Moderator:

Do not go to extremes,

Forget not your noble dreams.

See how the prudent boys

Restrain themselves in joys.The Feasters:

The cricket sings in the hall,

The year’ll take leave of all.

Let’s dance and sing tonight

To catch time in its flight.The Moderator:

Enjoy you surely may,

But heed what the elders say.

If you have no control,

You may soon lose your soul.The Feasters:

The cricket sings in the hall,

The year is beyond recall.

Let’s make the best of life:

Time’s like a butcher’s knife.The Moderator:

I know that life is brief;

But too much joy brings grief.

Beware of the charms of beauty:

True peace is found in duty.

Nor does Confucian joy disregard human love. In the Book of Songs, which is said to have been compiled by Confucius himself, and which he never tired of recommending to his pupils, and even to his own son, there are love poems of the best sort.

Confucianism seeks harmony in human relations, and when it expresses itself in poetry, it radiates a certain fragrance of sympathy that warms the heart. Nothing that is of interest to man as man is alien to it. It does not despise any human feelings, affections, desires, and appetites; it only insists that they should conform to the ideal of harmony.

The Joy of the Taoists

While the Confucianists sought for joy in the harmony of the human world, the Taoists found their joy in the harmony of existence between the individual and the universe. They aspired to transcend the human hive and to live in the bosom of Nature. A typical expression of the Taoist ideal is the poem by Lu Yun, who lived in the fourth century:

Beyond the dusty world,

I enjoy solitude and peace. I shut my door,

I close my windows. Harmony is my spring,

Purity my autumn.

Attuned to the seasons,

My cottage becomes a universe.

Lu Yun’s ideal man, although he lived in isolation, was really no isolationist, because he was one with the universe, his spirit being tuned to the rhythm of Nature. Unlike the Confucianist, who found happiness chiefly in the fellowship of like-minded people, the Taoist felt at home when he was alone in communion with Nature.

It is not surprising then, to find that, while Confucianism set great store by scholarship, Taoism accounted scholarly learning of little worth and even advocated its abandonment:

You have heard Confucius say that riches and honors improperly obtained were so many fleeting clouds to him. The Taoist seems to go a step further. To him all riches and honors, whether properly or improperly obtained, are nothing. As the great Taoist, Chuang Tsu, put it, the man of the Tao “lets the gold lie hidden in the hill, and the pearls in the deep; he considers not poverty or money to be any gain, he keeps aloof from riches and honors, he rejoices not in long life, and grieves not for early death; he does not consider prosperity a glory, nor is he ashamed of indigence; he would not grasp at the gain of the whole world to be held as his own private portion; he would not desire to rule over the whole world as his own private distinction. His distinction is in understanding that all things belong to the one treasury, and that death and life should be viewed in the same way.

The joy of the Taoist is the joy of non-attachment, of interior freedom. It lacks the warmth of the Confucian joy, but there is a breeziness about it which gives refreshment to the spirit. A good illustration will be found in “The Fisherman’s Songs,” written by Prince Li Yu. Note that these songs were written by a prince, who, despite his life in a palace, was miserable and envied the freedom of the fishermen. Here are the words of Prince Li Yu:

THE FISHERMAN’S SONG

The foam of the waves stimulates endless drifts of snow.

The peach-trees and the pear-trees silently form a battalion of spring.

A bottle of wine, An angling line,

How many men share the happiness that’s mine?

An oar of spring breeze playing about a leaf of a boat.

A tiny hook at the end of the silken cord.

An islet of flowers, A jugful of wine,

Over the boundless waves liberty is mine.

Many a Chinese scholar began as a Confucianist, but as he grew older, he became more and more Taoistic in his ways of thinking and feeling.

In the teachings of Taoism can be found the beginning of that spiritual detachment which was arrived at by the Christian saints and which is so wonderfully summed up in these paradoxical lines written by St. John of the Cross: “To possess everything, desire to possess nothing. To be everything, desire to be nothing.”

The Joy of the Buddhists

We come, now, to Zen Buddhism, which, to my mind, is a typically Chinese product. The German philosopher, Hermann Keyserling, in his book, The Travel Diary of a Philosopher, speaking of Confucianism and Taoism in China, says:

Kung Fu Tse (Confucius) and Lao Tse represent the opposite poles of possible perfection; the one represents the perfection of appearance, the other the perfection of significance; the former, the perfection within the sphere of the materialized, the latter, within the non-materialized; therefore, they cannot be measured with the same gauge.

On the whole, I think that Keyserling’s appraisal is right, if we confine our study to the natural wisdom of man. But if Confucianism and Taoism represent the opposite poles of possible perfection, one may wonder: Where does Buddhism come in? I think it represents an attempt to harmonize the two poles by transcending them both. The Zen Buddhist aspires to reach the Other Shore by standing right where he is. He sees all things in the light of eternity. For him every experience in life, however ordinary it may be, is charged with wonderful significance, because it is a springboard from which to jump into the ocean of mystery. Apparently, he is living in the same world as others, but subjectively he is living in a new heaven and a new earth. His joy is the joy of a sudden awakening, upon which one gets a glimpse of the very nature of things. In his momentary raptures, all fears and sorrows are forgotten, and life is no more than a play on motion picture film. In such a state, one acquires a sense of universal compassion for all sentient beings.

The Zen Buddhist, viewing the universe in the light of eternity, is unmindful of all the billions of years of its existence and sees it as a magical flower blooming only for a single instant and then disappearing forever. Or, to change the figure of speech, all the pageants of life seem to him like the speeding of a racehorse watched through a crevice in a wall. Yet, with the Zen masters, while all apparently permanent things become transient, the most transient things acquire an eternal significance. The notes of a singing bird, the fragrance of a flower, the rippling of a brook, the casual reunion of old friends, the whisper of a lover, the echoes of a church bell—all these things have an eternal quality, bathed as they are in the ocean of mystery. The spring flowers look prettier, and the mountain stream runs cooler and more transparent. This may be called aesthetical contemplation. This is why the greatest Chinese artists have drawn their inspiration from Zen Buddhism.

Let me relate to you a charming anecdote about the great Zen Master, Hsuan Sha. One day, Hsuan Sha had ascended to his speaker’s platform and was ready to deliver a discourse, when he heard the twitter of a swallow outside the hall. Abruptly, he remarked to his audience, “What a wonderful sermon on reality!” Thereupon, he came down from the platform and retired to his room.

Many of the poems of the T’ang Dynasty are saturated with the spirit of Zen. I will quote one which I like very much, and which seems to me to express a sudden invasion of eternity into the realm of time:

A NIGHT-MOORING OUTSIDE THE CITY OF SOOCHOW

by Chang ChiThe moon has gone down;

The crows are cawing;

The sky is filled with frost.

The maple-trees and the fisherman’s lanterns

Accompany my fitful slumbers.

Suddenly, from the Cold Hill Temple beyond the city of Soochow,

Come echoes of the midnight-bell to a passing boat!

C.G. Jung calls Zen Buddhism “one of the most wonderful blossoms of the Chinese spirit.” Now, what is the most fundamental characteristic of the Chinese spirit? To my mind, it is the union of the abstract with the concrete; of the universal with the particular; of utmost unearthliness with complete earthliness; of transcendental idealism with a commonplace practicality. This union is not a matter of theoretical synthesis, but a matter of personal experience. The idea that the ordinary duties of one’s daily life are charged with spiritual significance, is typically Chinese. D.T. Suzuki finds in this an expression of the Chinese people’s characteristic industry and practicality. Hence he finds it quite logical for the Zen teachers to insist on service to others—doing for others—as the expression of an understanding of spiritual values. For, says Dr. Suzuki, mystics are always practical men—not too absorbed in things unearthly or of the other world to be concerned with the needs of this life.

Once again, we find in the thinking of the Chinese sages the beginning of an approach to the perfection of the Christian saints. I know one person who attained a sudden awakening such as I have just described—an awakening to the transitory and fluid nature of the cosmos, which ordinarily appears so solid and so permanent—by the reading of the four-line poem expressing the philosophy of Zen Buddhism. It was written by Sui Yang-ti:

FLOWERS AND MOONLIGHT ON THE SPRING RIVER

The evening river is level and motionless—

The spring colors just open to their full.

Suddenly a wave carries the moon away

And the tidal water comes with its freight of stars.

This poem is innocent enough, but it opened the interior eye of that reader to the transitory nature of the Cosmos, which ordinarily appears so permanent. Thus, Zen makes you see into the work of creation, although it does not claim to interview the Creator himself.

Shakespeare was steeped in the spirit of Zen. Shakespeare who made Prospero declare near the end of The Tempest:

Our revels now are ended. These our actors,

As I foretold you, were all spirits and

Are melted into the air, into thin air;

And, like the baseless fabric of this vision,

The cloud-capp’d towers, the gorgeous palaces,

The solemn temples, the great globe itself,

Yea, all which it inherit, shall dissolve

And, like this in substantial pageant faded,

Leave not a rack behind.

We are such stuff

As dreams are made on, and our little life

Is rounded with a sleep.

It would seem that the spirit of Zen leads only to a negative result, and has nothing to contribute toward joy. Yet, the realization that we are all passing shadows does a great deal by way of lifting the burden of sorrows from the heart of a sufferer. It also prepares the way for a true religious life, for by showing that there is no abiding city in this world, it gives a salutary warning to the spirit of man against seeking rest where it cannot be found.

Conclusions

I have tried to depict three types of joy corresponding to the three schools of philosophy that have permeated the spirit of the Chinese people throughout the ages. Confucianism is humanistic, and its joy is the joy of a virtuous life. Taoism is pantheistic, and its joy is the joy of feeling at one with the cosmos. Zen Buddhism is otherworldly, and its joy comes from the sudden illumination concerning the nothingness of the visible world. I have only touched upon the joy of Christian saints, because this belongs to a higher order than that of the sages.

The Christian joy contains all the three forms of joy that were known to the Chinese sages. It knows the Confucian joy, which springs from fraternal love and filial piety; but it transcends it, just as the theological virtues transcend the moral virtues. The Christian saint knows also the joy of the Taoistic sage, but he does not content himself with a promiscuous union with the creation; he rests in the Creator and enjoys his union with the whole creation in him; through him, and for him. The Taoistic union with Nature is somewhat like free love, which may give momentary joys; but the Christian union with Nature is like the Sacrament of Marriage, which is a source of deeper and more stable joy, foreshadowing eternal bliss and borrowing therefrom a heavenly luster. The Christian saint, above all, knows the ecstatic and rapturous joys of the mystics, but, unlike the Buddhists, his transports are not self-induced— he simply rides on the tides of the Holy Spirit.

The Christian joy springs from three levels: Nature, man and God, with God as the Ultimate Source. This is why the Christian saints could sincerely fraternize with Nature without being drowned in the ocean of the cosmos. St. Francis loved and enjoyed Nature with the liberty of spirit characteristic of the children of God. He had all the joys known to the pantheists and more, and at the same time, he did not have to regard himself as a cosmic ganglion. Similarly, St. Vincent de Paul and Father Damien loved their neighbors so generously as to be glad to suffer with them and for them. How many missionaries have laid down their lives for their fellow-beings in the far-distant countries! But nobody would accuse them of being all-too-human and sentimental. St. Paul was made joyful in his contemplation of God, but he was at the same time as sober as any Confucian gentleman in his dealings with men, and as unattached as any Taoist hermit or Buddhist bonze to human riches and glories. Only grace can fulfill the aspirations of nature.

From these examples, it should be clear that the Christian saints possess a higher and richer joy than the pagan sages ever did. Compared with the Christian joy, the joys of the philosophers are but crumbs from the real Feast of Life. In truth, there is something pathetic about them; they are, at best, groanings and yearnings for the Joyful News of the Incarnation, for the restoration of the Garden of Delight. But what about those Christians who pass through their lives so joylessly that they have to seek external pleasures and excitements to kill time? They do not even seem to know what the Oriental sages knew so well: unless one finds happiness in the interior life, one will not be happy anywhere else. For, as Christ has told us, “The Kingdom of Heaven is within you.”

Now it is the aim of the Christian apostolate to preserve and to perfect—not to destroy—whatever of truth it finds in the traditions of a people, and there are many such elements in the teachings of the Chinese sages—Confucius, Lao Tse, and the teachers of Zen Buddhism. These teachings have left their influence upon the people in many parts of the world. Hence, it is good for all who would promote the Christian apostolate in our times, and especially for those who would be prepared for a “philosopher’s apostolate,” to know where the seeds of truth are to be found in the Oriental fields of thought. Upon the trees of culture which spring from these seeds, we may hope to engraft the life-giving Gospel revealed by the Author of all grace and truth and the Source of all our hope for happiness.

It is here that the Oriental ideas of harmony and joy have value, for “Gospel” means “Joyful News.” It is only when we appreciate and radiate from ourselves the joy embodied in the Christian Gospel that we can effectively work as missionaries. Too many Christians fail to reflect this Divine joy. They live as though Christ had never been born, crucified, and risen from the dead, and yet they talk about “Christianizing” others! In their endless searching for happiness in the transient and meaningless pleasures of the world, they are indeed seeking after husks fit only for the swine. The Oriental sages at least appreciated the little crumbs of the Bread of Truth which they found in their lifelong searchings. Were they far wrong in identifying joy with music? I think not, because music is the art of harmony par excellence. The sages knew that joy follows from interior harmony. They knew, also, that interior harmony means development of the human personality.

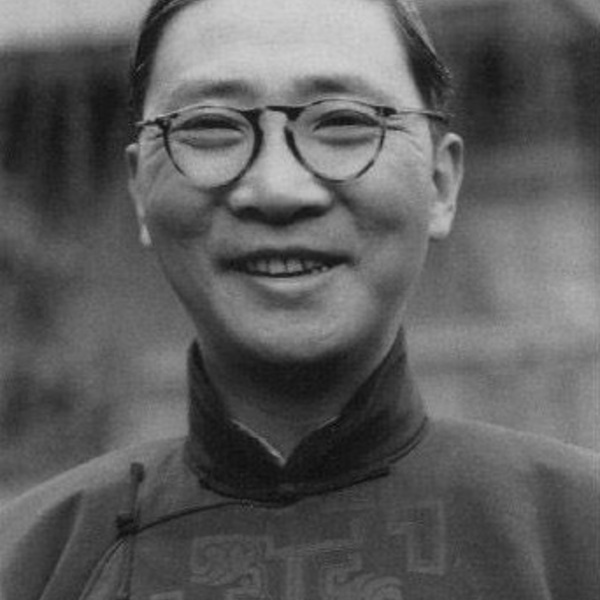

EDITORIAL NOTE: This essay is excerpted from Chinese Humanism and Christian Spirituality. Copyright ©Angelico Press, 2017. Reprinted by arrangement with Angelico Press. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.