Materialistic economism must logically lead to passive fatalism, because it is not personhood with its creative strivings but rather the im-personal economic process that determines the paths of history. Here there is no place for good and evil, or for any ideal values at all. But in practice, in complete inconsistency with its doctrine, socialism is developing in this recent era the greatest historical dynamism, namely “revolutionism.” Since 1789, the spirit of revolution has been hovering over Europe, penetrating deeper and deeper, absorbing into itself new social material, such that society in our time is beginning to be defined by its relationship to revolution, either for or against it.

Revolution is a fact and a principle. As a fact, revolutions take place with an elemental anarchy, they are like the eruption of a volcano, spewing lava and ash, or like an earthquake altering the strata, bringing some materials down and raising others up. The elemental powers are already evil in their irrationality, and even more so when man himself becomes such an element. Beastly savagery and frenzy are aroused, and in the masses there awaken age-old resentment, vengeful malice, and built-up envy—of course, alongside the heroic enthusiasm of individual persons, leaders, or groups.

It is not clear but rather filthy and muddy water that the bursting Acheron bears. Historical earthquakes are never “moral idylls which could satisfy school teachers,” as even Hegel noted. In the rushing stream of revolution, there comes to the surface, like foam, the baseness of humanity, which is often hidden in the darkness—the worst in man arises so that, I suppose, the best might also be revealed [1 Cor 11:19]. The violence and despotism of the oligarchy, the Red Terror, along with revolutionary hypocrisy, demagoguery, and careerism, reflect the wild and uniquely possessed state of the masses and their “leaders.”

As a principle, revolution is a fundamental break in the thread of a historical tradition, the wish to begin history again, starting with oneself. The pathos of destruction is here the pathos of creation. Barbarization occurs here not only through the altering of social strata but also as a consequence of the general anti-cultural stance of revolution’s relationship to the past, even if in practice it serves the culture of the future. Therefore it is not accidental that nihilistic revolt against historical tradition directs itself against faith as well, that it becomes “militant atheism.” One cannot explain this solely by appeal to the sins of ecclesiastical institutions, which are here exposed and punished. Revolution bears within itself a general nihilistic enmity towards values and towards the holy, and it would be incomprehensible if earthly mutiny did not recognize itself as an uprising against heaven too, if it did not cross over into theomachy.

This is all true, but clearly revolution is not the normal state of souls, so when exactly does illness become attractive and catastrophe good? Furthermore, illness has its own sufficient grounds, its causes, which are often very profound and reach far in the past. The executioners here become historical victims too, and those who bear the guilt for them are all who have promoted revolutions, either actively or passively. Revolutions are certainly not made by the revolutionaries themselves, who in this regard fall into a false historical hubris; rather, they themselves (along with the counter-revolutionaries) are made by the revolution. What is certain is that there exists a certain idée-force of revolution, the explosive that sets in motion inert matter, and this is, in addition to envy, also a special faith and a pathos.

In the idea of revolution what finds expression first of all is a striving towards the future, a thirst for it and a faith in it—amor futuri. In it there is contained a certain ideal for the future and, most importantly, a certain vision, a projection of this future from the place of the present; its soul in this sense consists in a utopia (u-“topos”), something as yet unrealized in any place but that must come to pass (this word “utopia” originates with Thomas More, the confessor and martyr of the Catholic Church in the sixteenth century). Utopias can differ, but generally speaking a utopia is the object of social faith, hope, and love, “the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen.”

Utopianism is not necessarily opposed to realism—it can and must be united with it. Here we have a difference between the goal and means, the task and its fulfillment. Utopia in this sense is an “ideal with changeable content,” with the former a matter of necessity and the latter of historical teleology. Only by a disturbance in the necessary balance does utopianism intrude into the sphere of realism, with delirium as a result, or realism loses its striving for the ideal and degenerates into a pragmatism emptied of ideals. The Christian ideal of the kingdom of God is realized in a series of changing historical objectives (which in our day consists, among other objectives, in the achievement of social justice united with personal freedom), together with their corresponding necessary practical measures (in this sphere it is possible to have practical disagreements, because Christianity, which is called to establish unity of spirit, cannot identify itself with any one program or party).

In essence, utopianism belongs to Old Testament messianism as much as it does to Christianity, but in recent times it has been effectively monopolized by revolutionary socialism. Although even in Marxism it is considered good form to repudiate “utopian socialism” for the sake of “scientific,” that is, realistic socialism, this too is of course no less utopian than other utopias. Utopia is always a fairy tale, a tale about the future, since from the present it is impossible to see the future, but it is also a prophecy about the future, for this future is already contained and anticipated in the present. Utopia is the inner nerve of the dynamism of history. “The heart lives in the future; the present brings dejection” (Pushkin); such is the law of the human heart, its dream. There is indeed a reverie that enervates, yet without a dream man cannot live. History is made not by sober prosaics but by dreamers, people of faith, prophets, “utopians.” For them the present “dejection” is only pre-history (Vorgeschichte), the prologue to history with its “dialectic,” where “Widerspruch ist Fortleitende” [conflict moves things forward] in realizing the mind of history—List der Vernunft [the cunning of Reason] (Hegel). And this dialectic turns out, by force of events, to be a revolution against a present they will not acknowledge, a present they are ready to sacrifice for the sake of the future—to sacrifice love of one’s neighbor in the name of “love for the distant.”

But once it has lost its spiritual equilibrium, faith becomes superstition or a fanatical reverie that is animated no longer by a vision of a coming city but by deceptive mirages. Utopianism, which constitutes the soul of revolution, is thus also missing—because of its lack of religious roots—spiritual equilibrium. Its social idealism is found in contradiction to that wingless positivism to which it is bound in the name of an imaginary “science.” The utopianism of Marx, like that of other positivists, is completely irrational, full of contradictions and religiously barren. Its ideas on history go no further than Vorgeschichte, the epochs of class conflict, but Geschichte itself is empty of content. Irreligious utopianism in revolutionary socialism, to the extent that it is not demagoguery, transforms into a feverish delirium, a Fata Morgana for the delirious in a waterless desert.

But, in the name of love, which “rejoices not in injustice but rejoices with the truth” (1 Cor 13:6), we must even here see an expression of a genuine thirst that does not know, that cannot find the religious font that would quench it; not understanding itself, it cannot recognize its own truth. The break with Christianity, and even with any faith in a personal God, visible in social idealism, in “progress,” in this acute recidivism into paganism, can seem definitive and irreversible (and the frenzies of sacrilege in Russia, together with the religious asphyxiation of the people and the antireligious inquisition, might convince us even more than the bacchanalia of the French Revolution did).

Socialist utopianists—wild and frenzied in Russia, sluggish and cold in other countries—make of social revolution a religious idol. But on the opposite side, the people of the Church see this as sufficient grounds for condemning the socialist utopianists and for washing their hands of any personal responsibility. There arise mutual estrangement, deafness, and a lack of understanding. The watershed between Christianity and neo-paganism (imagining itself to be atheism) is certainly not marked by the imaginary line of “science.” (In this regard, we should sooner speak of an approaching meeting of faith and knowledge rather than the reverse, and present-day materialism is, generally speaking, as much obscurantism as it is а failure of thought).

The watershed is instead marked by historical dynamism, by the relationship to what is socially efficacious. One cannot, of course, downplay the ill will and, consequently, the deliberate, conscious enmity towards the holy that is present in “militant atheism,” and especially among its ringleaders, the ranking functionaries of the revolution and their oprichniki ho make a career out of Christ-betrayal and spiritual infanticide. But Satan, besides his genuine and terrifying face, also takes on the appearance of an angel of light [2 Cor 11:14], clothing himself in the garb of social justice, and the atheist movement is animated by the deception of the father of lies who created the false utopia of a godless world with him as its lord. Spiritual sobriety, as well as simple truthfulness, demand a thorough investigation of a position before issuing a definitive verdict and submitting the case, as it were, to a higher court. And where many are prone to see а spiritual confrontation, in which all guilt is found solely on one side, is this not a certain misunderstanding created by intellectual poverty and ill will but also by the presence of guilt on the other side as well?

“Repent—metanoeîte (come to your senses, examine yourself), for the Kingdom of God is at hand” [Matt 3:2]. These words from the Forerunner, and later from Christ, bear the most extensive meaning and have a special social-historical application. Does not this “repent” call us to new achievements, and especially to the testing and re-examination of what we are accustomed to consider self-evident and on which we rest complacently? Do the people of the Church seek social justice or the social utopia corresponding to the needs of their era, with its unique dynamism, or do they remain satisfied only with a static conservatism that for them exhaustively sums up “fidelity to tradition”? Does there exist for us a historical future with its new tasks, or is the entirety of Christian historiosophy completely exhausted by the expectation of a global catastrophe in which we can find only the devalorization of all historical values—alles, was entsteht, ist wert dass es zu Grunde geht? [“All that comes to be deserves to perish wretchedly”]. But there exists a spiritual horror vacui [i.e., “nature abhors a vacuum”] and can we be surprised if people, not finding a way to quench the demands of their conscience, go out to seek it in a “ far country” [Luke 15:13]? But it was no so from the beginning [Matt 19:8].

No one can say that a sense of history is lacking in the Old Testament, for the Old Testament itself is sacred history wholly striving towards the coming messianic kingdom. And not only that—in its schema the entirety of global history is also included (we see this already in the book of Genesis, later in the prophets, particularly in that prototype of subsequent apocalypses, the book of Daniel). In Old Testament prophecies, we find such ambitious utopias (in the positive sense of the word, of course) that are completely unparalleled in their audacity. Here we find not only religious historiosophy but also historical tasks inspired by ideals, tasks surpassing even our current historical reality. On that score, the preaching of the prophets (Amos, Isaiah, Hosea) contains, among its many aspects, a social meaning as well. Is it any different in the New Testament? Does it abolish the prophecies of the Old Testament? Neither dogmatically nor historically can this be admitted. Nonetheless the general feeling of life radically changes in the New Testament: into its depths there is introduced an antinomism—with both its wisdom and its difficulty— that the Old Testament man, on account of a certain naiveté, could not accommodate.

The kingdom of God is summoned (“thy kingdom come”) into the world, but the kingdom itself is not of this world [John 18:36]. It is entòs hymō̂n, that is, first of all “within us” but also “among us” [Luke 17:21]. In relation to the world, a tragic bifurcation thus occurs, of love for the world and simultaneous enmity towards it. Due to the complexity of this relationship in Christianity, there is no room either for the messianic paradise of Jewish apocalyptic or for the earthly paradise of socialism. The question can even arise—does history exist at all for Christianity, or is it an inconquerable duration of empty time in which there is already nothing left to accomplish, “the last days?”

This conclusion would mean that, since the time of the incarnation, everything has already been accomplished on the divine side. But for Christian humanity, these last days also constitute their own aeon, with its own achievements and revelations. The New Testament Apocalypse is a revelation concerning history, and not just concerning its end, as it is often interpreted. Here in its symbolic images (which are to some extent typical of the apocalyptic genre in general) there is revealed that struggle of two principles which constitutes the tragedy of history, with alternating victories аnd defeats; here we see mentioned not only the triumph of the Beast with his False Prophet but also the phenomenon of the thousand-year reign of Christ on earth. Other places in the New Testament fill in the essential details: the preaching of the gospel to all nations (Matt 24:2) and its connection with other events, the conversion of Israel as “life from the dead” (Rom 11:15), the manifestation of the “adversary.” All these are borders demarcating historical epochs.

The future in its essence has been heralded by the Holy Spirit (John 16:13), but in its particulars it is kept in the dark, for it a matter of human creative work as well. Therefore history does exist within the borders of the “last days”; it is not a bad infinity eternalizing the intermingling of good and evil, as our contemporary paganism thinks, but it possesses an organic end, a transcensus to a higher state, which is accomplished by the power of God. This transcensus is not itself a simple historical event, for it is transcendent to history, and it does not take place in historical time (“and the angel swore that times will be no more” [Rev 10:6]). History with its apocalypse, although intrinsically dependent on eschatology, cannot be extrinsically oriented towards it, for the end lies not within history but beyond it, outside the limits of its horizon, beyond its border.

The fact that these two perspectives blend into each other is often abused by those seeking to save themselves from historical panic by а flight into eschatology. The thought of the end should unceasingly ring within the inner man (along with the remembrance of death and the judgment), but it is forbidden for us to determine the times and seasons [Acts 1:7], to falsely prophesy concerning them. It is not for this reason that revelation of the end was given to us (concerning the general resurrection), but instead for the increase of vigilance (“watch,” Matt 24:42) and as a certain guarantee of the victory of good, of a positive outcome to history.

History, religiously experienced, is the apocalypse in the process of accomplishment, apocalypse here understood not as eschatology but as historiosophy connected with the feeling of striving towards the future, with the consciousness of pending tasks and continuing historical work. Time is measured not in years but in deeds, and if a person senses that pending tasks and historical possibilities lie before him, he cannot think of the end passively, unless all of history for him represents solely the unending triumph of the Antichrist and constitutes nothing more than a preparation for the latter’s personal appearance. Quite the opposite—Christianity calls us to courage, labor, inspiration. Christ praises the “faithful and good” servant who put to use his “talent,” and he condemns the “ wicked and lazy” servant who buried it [Matt 25:14–30]. Christian historiosophy unveils apocalyptic expanses and distances in the quest from the present city to the coming one, for “the form of this world is passing away” [1 Cor 7:31].

And that is why revolutionary dynamism, which remains blind and elemental in its atheism, is capable here of coming to know itself in its own truth. The real idea of progress, that is, of movement towards a goal, and an absolute goal at that—the kingdom of God—can be accommodated only within Christian historiosophy, which reconciles itself with nothing parochial and limited or with any historical philistinism. This idea was revealed in the days of early Christianity’s springtime, when in a world weighed down by the flesh there arose to oppose that world a small flock exhibiting a heroic indifference, which (according to Celsus) ate away at the very foundations of antiquity in its fundamental values, both of government and of culture. But this rejection of the world on their part was tied to their expectation of the end and the resultant detachment from history and its affairs. This is the source of early Christianity’s social quietism, on the one hand (“let each one remain in the station in which he was called,” 1 Cor 7:20), and its unique conservatism, on the other (“There is no power but from God” [Rom 13:1]), though the latter is often accompanied by the threatening tones of the apocalypse.

This was a unique apoliticism that attached importance only to a person’s inner state (hence the seeming indifference towards slavery, an institution that was historically undermined from within, of course, precisely through Christianity). The primacy of the internal over the external remains here unaddressed; it is precisely this that serves as the spiritual foundation of the community. Yet this primacy does not mean public indifferentism and a lack of values. This public absenteeism, which in early Christianity seemed pragmatically wise and was in fact the only possibility at the time, would become a weakness when Christianity gained influence in government and society.

In reality, Christianity served as the spiritual leaven for a new society, for in it was born a new sort of personhood, and its actual influence reached, of course, far beyond the limits of the activities of the Church’s own institutions. What is more, it is impossible to deny that Church communities, as is the case with the rest of humanity, rarely ever lived up to the height of their calling. Furthermore, they often became a stronghold of conservatism, or, at all events, of unprogressive attitudes, both externally and internally. The more internal opposition on the part of the Church towards revolutionism (at least of the nihilistic kind) flows simply from her faithfulness to tradition, which permeates her entire life.

Tradition is the living memory of the Church, as opposed to the historical amnesia of those children of revolution, who would date history’s beginning with themselves. There is simple human dignity, which does not reconcile itself with this nihilism’s spiritual tastelessness; there is historical consciousness, which perceives this abolishing of history as a barbarization; and there is, finally, the Church’s consciousness, for whom a fundamental break with tradition constitutes the most cruel heresy. Yet at the same time, fidelity to tradition is not equivalent to immobility and it is not bound to what is obsolete and antiquated; that is not fidelity to tradition but simply secularized conservatism, not always sufficiently distinguished from the former. Unfortunately, on account of human weakness, much unecclesial contraband is smuggled in under the banner of the Church, and in its centuries-long journey, many things have stuck to the bottom of the Church’s ship that are foreign and at times essentially inimical to it—the very thing that provokes the schadenfreude of the atheists who have skillfully demonstrated this in their exhibitions and museums. The fire of revolution—however painful—proves here to be purifying even for the Church community.

But in any case, the relationship of Christianity to the world and its values can by no means remain only an immanent relationship, as in neo-paganism. When eyes are turned to heaven, then they are blind to what surrounds them, and the call of eternity creates indifference towards the “dreary songs of earth” (Lermontov). There exists a Christian freedom from the world (prevalent especially in former ages) that seeks to realize itself in an external flight from the world. But this flight with its disinterest in values could not, practically, be realized fully even in anchoritic monasticism, which carries into the desert worldly passions; moreover, even from the desert, monasticism strives, or rather is called, to make an impact on the world. It was precisely in monasteries that there arose, on occasion, Christian utopias that later became driving forces in history (“The Third Rome,” holy empire, theocratic government), and one could even say that the more fiery and sincere the spiritual intensity there, the more effective it was in the world (examples: St. Francis and Franciscan spirituality, Luther and the Reformation).

Yet not infrequently this rejection of the world results in conservatism towards the world, and this conservatism then goes even further, becoming something that could hardly be called world-denying, for that matter. One can generally say that in Christianity a search is always ongoing for the guiding idea of the historical development of an epoch, and everyday conservatism cannot be considered here as the normal or sole variety of Christian social consciousness. Of course, between atheist revolution and Christian society a chasm lies. But does this mean that Christianity, by virtue of its “supra-historicity,” knows only static conservatism, or can it and must it know dynamic effectiveness too? Is a Christian reformism possible, one animated by the idea of the kingdom of God and possessing its historical utopia, or rather, utopias—not, of course, of “paradise on earth,” but of victory, or rather, of the victory of good on the path of world-historical tragedy leading to the final separation of light and darkness?

Here we meet the fundamental question of Christian life in our time, namely (in its contemporary formulation): how can we “enchurch the culture?” Once again the Sphinx of history questions our mind, our heart, and our freedom: yes or no? This question is th e historical watershed dividing the waters. The simplest option here is to avoid the question under the pretext of a separation in the individual’s soul between the things of Caesar and those of God. This is Protestantism’s answer, and it legitimizes the secularization now suffocating the world. Perhaps this answer had a historical justification in the effort to free itself from papal theocracy, but the same separation is not infrequently pronounced in the name of Orthodoxy too. Ascetical rejection of the world, personal pietism, these—in a spirit of world-denying “apoliticism”— are considered here the exhaustive answer, while the vacant battleground is immediately seized by the ruling powers or by purely “political” passions.

The Church is indeed “apolitical,” in the sense that her eternal values cannot be identified with any relative goals or historical institutions (in the same way that the party of untrammeled autocracy was considered by us to be the only and truly Orthodox option). The Church must be not a party but the public conscience that permits neither political accommodation nor indifferentism under the pretext of humility. Yet she must strive not to isolate herself from society (which results in secularization) but rather to spiritually take hold of society from within (this was the ideal of “free theocracy” of the early Solovyov and the late Dostoevsky).

Before our very eyes, the different Christian confessions, each in their own way, together and individually, are taking steps (granted, still hesitant steps) along the path towards a Christian society. On a global scale (unfortunately, without Catholicism), this movement is connected with the name of the Stockholm conference of 1925. Responsibly joining ranks with it were representatives of different Orthodox Churches, who thereby took upon themselves the responsibility of educating the nations in the spirit of social Christianity. One of the weakest sides of this movement is insufficient clarity—to say the least—on the theoretical, or rather, dogmatic foundations of the movement for religiously overcoming secularization.

The Church places on its own conscience the burden of society, and this not just in practice, as hitherto been the case, but also on principle, and for this it is necessary to have faith, enthusiasm, vocation. We must comprehend the revelation of God in history as an apocalypse in progress that leads to the fullness of historical achievements and in this sense also to the end of history, not just to a simple alternation of events in their pragmatic comprehensibility. And in this task there should be another means of comprehending history: the living sense of the incompleteness of history (Vorgeschichte) that still leaves room for “utopia,” for what does not exist but must yet arrive, for an ideal and for hope.

Christianity, in its idea of the kingdom of God, possesses such a universal, boundless ideal, which contains in itself all good human goals and achievements. But it also possesses its own promise, which in the symbolic language of the Apocalypse is designated as the coming of the thousand-year reign of Christ on earth (Rev 20). This symbol, which is the guiding star of history, has already for a long while been locked away due to a one-sided interpretation, such that it is considered almost a specific “heresy” not to accept the prevailing interpretation of it, one that leaves nothing of the symbol’s meaning intact. But this maximal manifestation of the kingdom of God on earth symbolized here not only cannot remain just a passively accepted prophecy (or one completely rejected for ideological reasons) but must even become an active “utopia,” a hope. Of course, this symbol by itself is abstract, but it is always being filled in with definite content, as the next step or achievement in history, as a call from the future addressed to the present. Out of panic or spiritual laziness or fatigue, false eschatologism rejects responsibility for history while nonetheless in practice (i.e., in a heathen fashion) it participates in history.

But since society is unavoidable, even if only as one’s particular fate, then it must make room for seeking the Christian justice of the kingdom of God, and—“seek, and ye shall find” [Matt 7:7]. The gifts of the Church are irrevocable [Rom 11:29], even if we ourselves refuse them and bury them in the ground [Matt 25:14–30]. But whatever fails to find a worthy response from contemporary ecclesiality imperceptibly becomes the possession of forces hostile to the Church. Who knows how many Sauls linger today in the atheist camp, seduced by its dynamism, because they found in us neither an audience for their questionings nor answers to them. It is power and truth that conquer, not evasive and [politically] accommodating apologetics. The tragic experience of our nation, as well as the threats of new clouds gathering above, call us to new paths of thought and life. “Thy youth shall be renewed like the eagle’s” [Ps 103:5]. Unceasing renewal is the law and condition of spiritual life, as well as of fidelity to living tradition.

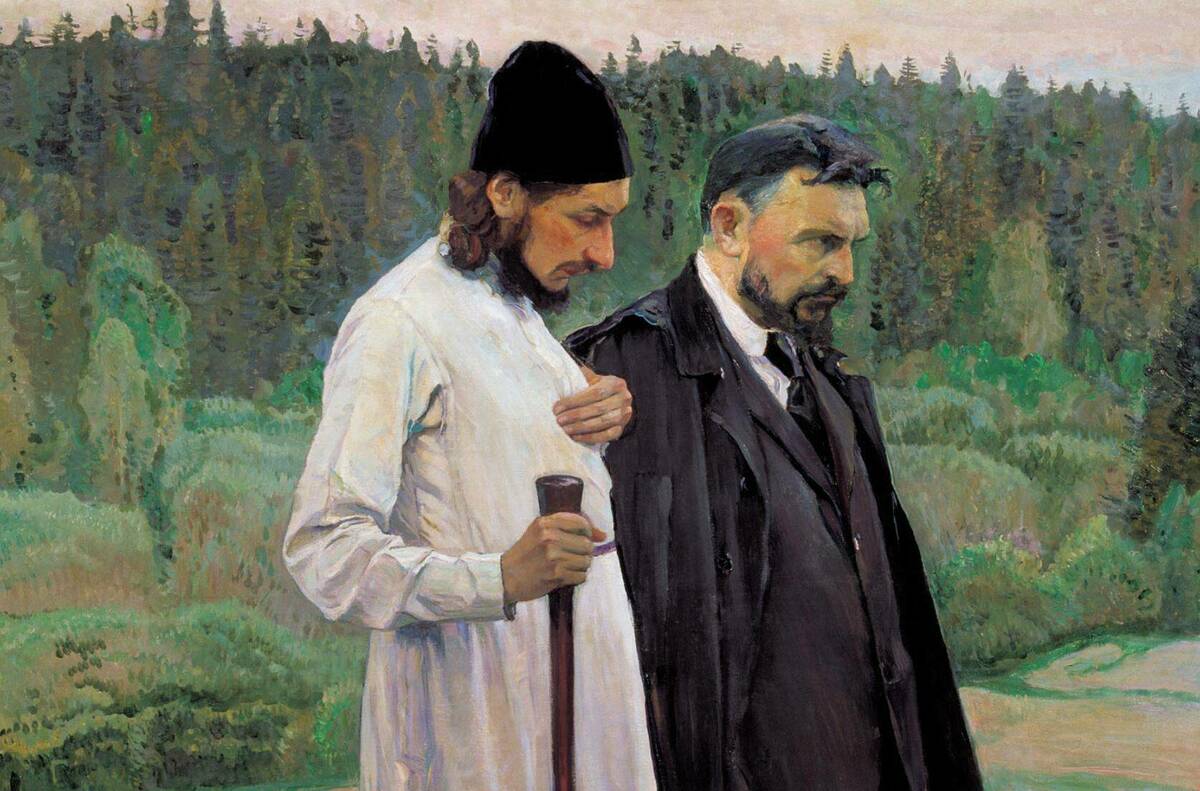

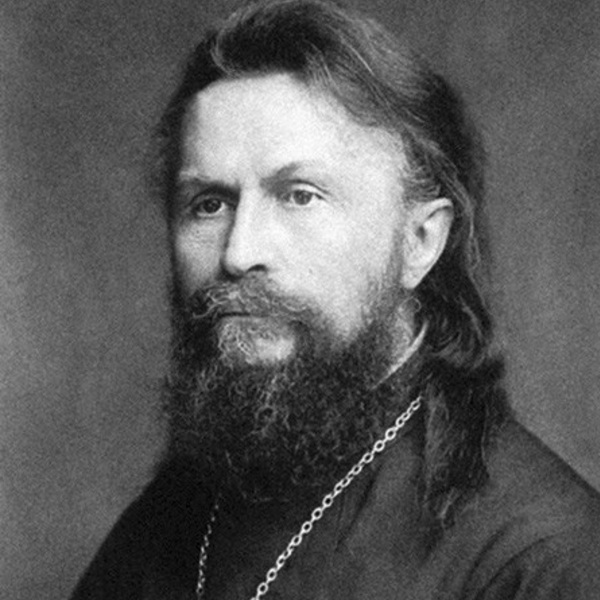

Editorial Note: This essay is an excerpt of the chapter "The Soul of Socialism (Part II)" (published in 1932) in Sergius Bulgakov's The Sophiology of Death Essays on Eschatology: Personal, Political, Universal translated by Roberto De La Noval, courtesy of Wipf and Stock.