How short a time ago, relatively, the small, new European world was easily seizing colonies everywhere, not only without anticipating any real resistance, but also usually despising any possible values in the conquered people's approach to life. On the face of it, it was an overwhelming success. There were no geographic frontiers [limits] to it. Western society expanded in a triumph of human independence and power. And all of a sudden in the 20th century came the discovery of its fragility and friability.

We now see that the conquests proved to be short lived and precarious—and this, in turn, points to defects in the Western view of the world which led to these conquests. Relations with the former colonial world now have turned into their opposite and the Western world often goes to extremes of subservience, but it is difficult yet to estimate the total size of the bill which former colonial countries will present to the West and it is difficult to predict whether the surrender not only of its last colonies, but of everything it owns, will be sufficient for the West to foot the bill.

—Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, “Harvard Address”

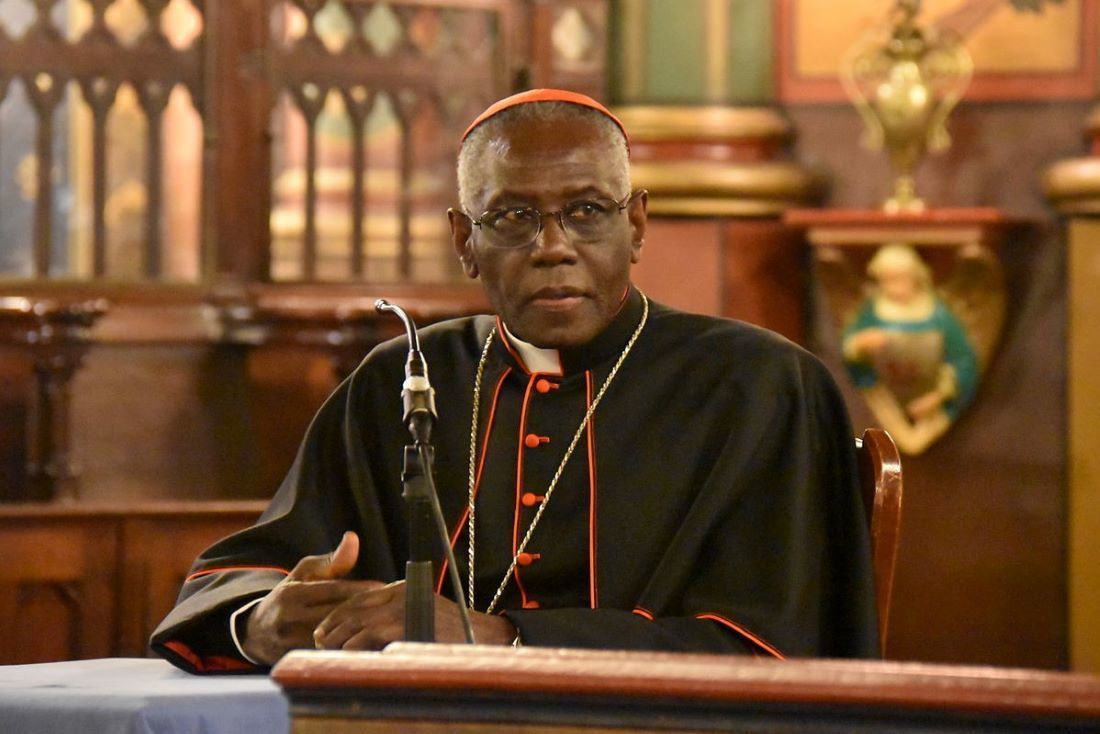

Earlier this year Cardinal Sarah found himself at the center of a renewed debate about clerical celibacy. His new book From the Depths of Our Hearts argues for a necessary link between celibacy and the priesthood. Some Catholics, citing the initial co-authorship of Pope Benedict, have seen this argument as a rebuke of Pope Francis’s willingness to ordain so-called “viri probati,” men whose character and faith make them candidates for ordination in regions where the shortage of priests is most acute. The typical ideological lines of demarcation have appeared. Some outlets laud the book’s dedication to tradition and foresight, while other ones question his motives—perhaps he is manipulating Benedict, using a respected figure to draw a line in the sand.

Although Cardinal Sarah often speaks about topics such as gender ideology, his recent book, The Day is Now Far Spent, paints a substantially more complicated portrait of the Guinean cleric. His love of the Latin Mass and opposition to contraception both feature in the book-length interview. However, what surprisingly lurks between the covers of this particular book is a strong commitment to Pope Francis’s holistic vision of the Church. More specifically, Cardinal Sarah spends pages upon pages highlighting two sicknesses that he believes define our era: capitalism and neo-colonialism.

While the African prelate sometimes sounds not unlike a vocal America-first Catholic, a thoughtful reading of his statements makes clear that these are incidental similarities, not ideological concurrences. Take, for example, his stance on the European refugee crisis. In an interview with the French magazine Valeurs Actuelles, he appeared to contradict Pope Francis’s position on immigration, saying “It is better to help people flourish in their culture than to encourage them to come to a Europe in full decadence . . . It is a false exegesis to use the word of God to promote migration.”

His reasoning, however, is not that migrants pollute or corrupt the cultures they enter. Instead, in The Day is Now Far Spent, he notes that Europe displays oligarchic tendencies. It takes in refugees with false promises, only to stick them in camps, stealing away their God-given rights:

In Europe, the migrants are deprived of their dignity. Human beings are parked in camps and condemned to wait without anything to do with their days. In France, the Calais Jungle was a disgrace. How is a man without a job supposed to find genuine fulfillment? The cultural and religious uprooting of Africans thrown into Western countries that are themselves going through an unprecedented crisis is a lethal compost.

The cardinal does not lay the blame for their migration at the feet of the refugees, but instead roundly criticizes European countries and global corporations for this debasement:

Entire nations have been ravaged economically by the unscrupulous multinationals that pillage national economies. Neo-colonial policies that infantilize governments are a disgrace. Is it any surprise, then, when populations flee such situations in streams? They conceal the truth, and they dare to wonder whether it is necessary to welcome the populations that arrive on European shores. And I am not [even] talking about the Mafia-like practices of those who exploit the migrants’ poverty.

He goes further, criticizing the West, and Europe in particular, for their hollow humanism. Countries and NGOs, he says, “organize humanitarian conferences by day and sell weapons at night.” “Diplomats and decision markers” put arms contracts and resource extraction before the lives of “thousands of Yemenite children.” Relaying a heartbreaking story about some of his countrymen who died in ships’ refrigeration units en route to Europe, he decries the deaths of countless impoverished Africans.

These horrors lead people to acts of terrorism. In his view, Muslims are our brothers. Speaking of his peaceful relationships with fellow People of the Book in Guinea, he blames Salafism and its counterparts on Europe’s spiritual emptiness and refusal to care for the least of these.

Quoting Pope Francis’s Laudato Si’, Cardinal Sarah preaches the need for Catholics to steward the environment, saying that the financial interests of multinational companies are among the greatest threats to God’s creation. “In Africa,” he comments, “we know this exploitation of the interests of the poor . . . They pollute the environment and leave the continent in endemic poverty.” At length, the cardinal condemns the ways in which mineral-rich Africa, having endured the colonialism of ages past, must now endure injustice upon injustice. Their riches are plundered, their homelands’ natural treasures left in shambles:

Alas, Africans know all too well the problems associated with the destruction of nature. Their minerals and other natural resources are often shamelessly pillaged and placed on the altar of financial interests. The rich countries do not care about the human and social consequences that they cause for defenseless populations.

Although we might suspect that Cardinal Sarah would dilute his criticisms by making these problems merely spiritual sicknesses, he warns explicitly that actually existing capitalism is the primary problem. His interviewer, Nicolas Diat, asks him about “a pantheon of modernist idols.” The Guinean prelate cuts to the chase, retorting “the idol of money dominates the others . . . Money runs the world. The worship of the golden calf is an obsession of the modern world.” Perhaps taken aback, Diat inquires how Cardinal Sarah “judge[s] the truth of capitalism in practice.” We might expect him to back down; he, however, does not:

A semantic shift has occurred. We no longer talk about capitalism but about economic liberalism or about a decentralized economy. The proponents of capitalism think that free competition is the only way to make progress.

The cardinal continues:

In reality, capitalism is based on the idol of money. The lure of gain gradually destroys all social bonds. Capitalism devours itself. Little by little, the market destroys the value of work. Man becomes a piece of merchandise. He is no longer his own. The result is a new form of slavery, a system in which a large part of the population is dependent on a little caste.

He concludes with some cold realism, “In these conditions, do solidarity and development still have any meaning?”

From this point, the cardinal, despite his condemnations of Marxism, even begins to use language reminiscent of that tradition. Citing the French novelist Émile Zola, he remarks that, even though some Christian bosses tried to protect workers in the 19th century, “the spirit of capitalism spread its law of domination” employing its twisted logic to undermine their efforts. The cardinal speaks of “a proletariat that was living in miserable, undignified conditions.” The least of these found themselves crushed by “a dominant bourgeois class.”

These historical conditions have led to a contemporary injustice—democracy itself no longer functions properly, with the rich buying undue representation and the poor left trampled underfoot. “Democracy is sick” and “Government of the people by the people has become the subjection of the people by high finance.”

These material realities lead to a spiritual sickness. Bishops and priests prize popularity, enrichment, and the ways of the world to the exclusion of defending the poor and marginalized. In rebuking them, Cardinal Sarah notes that “The common good is the only objective.” We must, he argues, return to a “contemplative attitude,” an approach that resists our becoming mere consumers, thrown to-and-fro by marketing, ignoring the plight of the millions of people and natural resources that our lifestyle oppresses and degrades:

A policy of unlimited productivity inevitably leads to human, cultural, or ecological catastrophes. Consumerism is a utopia that corrupts and debases man to the purely earthly level. This religion of immediacy looks only to the profit motive. Man no longer counts. He is bothersome. In some cases, why not replace him with robots? I think it is urgent for us to become reacquainted with the experience of gratuitousness. The most profoundly human acts are characterized by gratuitousness. It is the prerequisite for friendship, beauty, study, contemplation, and prayer. A world without gratuitousness is an inhuman world. I call on Christians to open oases of gratuitousness in the desert of triumphant profitability.

In this sense, the cardinal is not unlike Pope Francis. He quotes the Holy Father throughout the book, even dedicating it to both him and Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI. His ultimate goal is unity, is the silencing of voices that would try to rend and tear the Church. The Day Is Now Far Spent, at times, has him sounding more like socialist and communist radicals than like comfortable pop-Catholic pundits. I suspect that Cardinal Sarah is well aware of this.

Looks can be deceiving and humankind cannot bear very much reality. How else can American readers be so blind as to have completely ignored these uncomfortable truths that trouble Cardinal Sarah so much? Our narrow American point of view obscures the ways in which a cleric, writing from an African perspective, calls us all to fundamentally reflect on how we live our lives, to discern how we participate in these manifestly unjust systems of global terror. Cardinal Sarah should not be so easily ignored by any American Catholic; his words stand as a rebuke, reminding us of what Saint Paul, drawing on the Psalms and Ecclesiastes, writes in his Letter to the Romans: “There is no one just, not one” (Rom 3:10). Sicut scriptum est quia non est iustus quisquam.