The world of Ukrainians split open like a fractured mirror on February 24, 2022,. This date will forever divide their lives into “before” and “after,” with each reflection marred by the renewed fight for what truly matters: freedom, dignity, solidarity, faith, hope, and love. While international efforts try to bind the wound with sanctions, the war’s true cost grows heavier with each passing day. The once-peaceful land now bears the weight of countless lost lives, tens of thousands silenced forever, and millions more forever scarred.

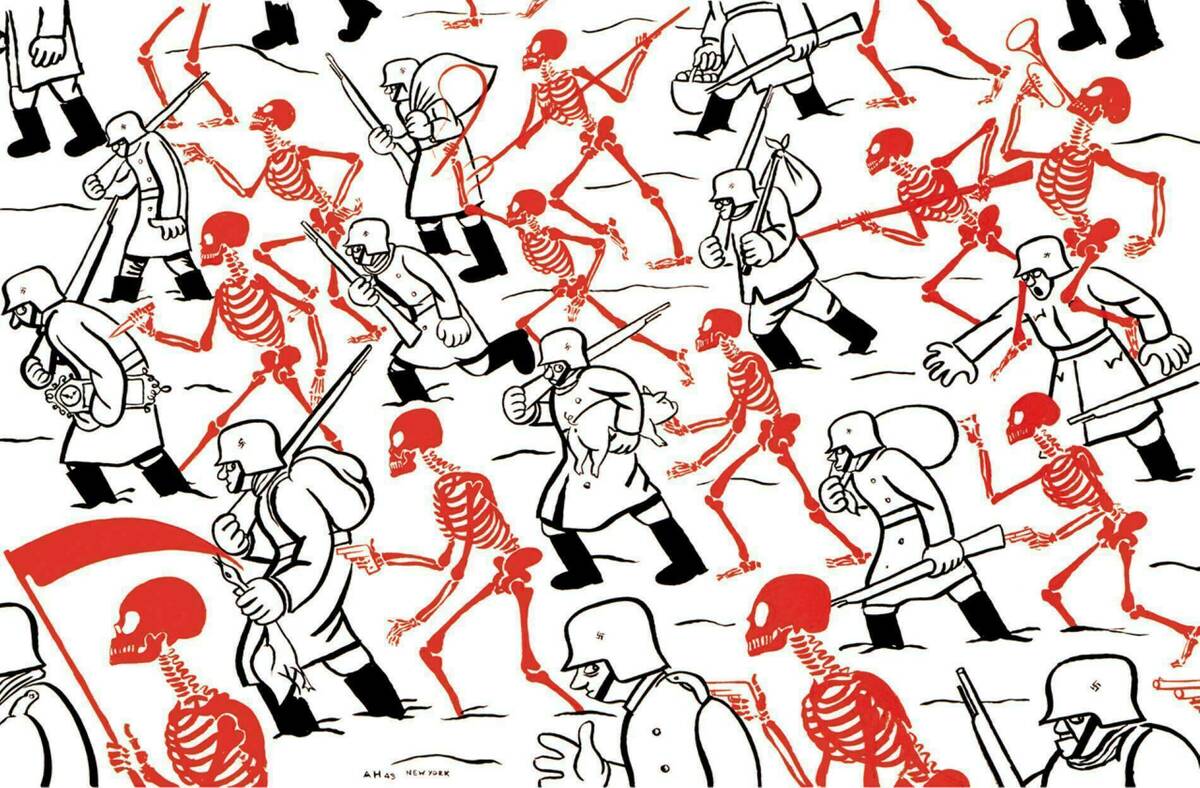

The war in Ukraine has become a stark litmus test, exposing a deeper crisis—the crisis of words. The once-powerful vow of “Never again” hangs heavy and hollow over the shattered lives in Mariupol, Hostomel, Bucha, Chernihiv, Lysychansk, Odessa, Mykolaiv, Dnipro, and countless other cities. While the horrors of World War II are etched in our collective memory, we find glimpses of hope amidst the darkness. Figures like Jürgen Moltmann, who discovered his faith as a German prisoner of war in British camps, and Chiara Lubich, who recognized that wartime godforsakenness could be overcome through solidarity, offer powerful testimonies.

However, it is crucial to remember that World War II was not a singular event. It followed World War I—“The war to end all wars” or the first “total war”—and now some claim the war in Ukraine ushers in a World War ІІІ. Maybe the names and numbers of war are not as important as those of the people suffering from it. Instead of fixating on labels and numbers, let us shift our focus to the human narratives.

When entire families burn alive under Russian airstrikes, as they did on the night of February 9, 2024, repeated pronouncements of “We are concerned” and “We pray” ring hollow and impotent. The police report from that night paints a horrifying picture: the ten-month-old baby’s body was unrecognizable, reduced to ashes by the inferno. Investigators believe the mother clung to her children, holding them close in a desperate embrace.

What words can truly describe such horror? What words can offer comfort and heal the wounds? Perhaps all we can do is echo Christ’s cry: “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (Matt 27:46; Mark 15:34), offering our suffering to God in lament as he did on the Cross. Yet, the Bible also offers a tapestry of human experience, woven with threads of both profound terror and remarkable resilience. Some passages chronicle unspeakable suffering, while others soar with the beauty of poetry and faith. The unspeakable experience needs the unspeakable words. As C.S. Lewis wrote, “Every war is a monument to an unanswered prayer.”[1]

Ukrainian writer Iya Kiva paints a tragic image: “Ukrainian poets remind me of people who, after a car crash, are the first ones to rush into the lane of oncoming traffic, desperately calling for help.”[2] Like John the Baptist, they prepare the way, not for a divine savior, but for a collective awakening to the human cost of war. Instead of asking if we need poets in war, the question becomes what role they play. They become the chroniclers of suffering, the witnesses to resilience, the voices that pierce the silence and demand action. They remind us that indifference is not an option, urging us to stand in solidarity with all who suffer. Ukrainians, something like prophets crying in the wilderness, become poets of their pain, their voices echoing the silent cries of those who feel forsaken while poets try to catch it.

What follows delves into the realm of war poetry, weaving a tapestry around the themes of the passion, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ. It embarks on a journey to unravel the profound experiences of godforsakenness and the embrace of death during wartime. Through phenomenological analysis, the argument focuses on two poignant poems that encapsulate the raw essence of these themes. “Death in Battle” by C.S. Lewis, the famous Christian apologist who was a soldier during World War I, and an untitled poem by Maksym Kryvtsov, a Ukrainian soldier who died in the ongoing war in Ukraine. United by their common theme of war's inherent godlessness and their grappling with suffering, the authors utilize poems to forge new paths of understanding. By examining these diverse voices across time and conflict, the article aims to deepen our understanding of the profound human struggle with Godforsakenness and death during wartime.

Writing About the Unspeakable

C.S. Lewis’s “Spirits in Bondage” unfolds across three distinct themes: “The Prison House,” “Hesitation,” and “Escape” describe a profound rebellion against a seemingly silent God that echoes through the suffering and grief of humanity. The poems are marked by an undeniable ambiguity and honesty, capturing the vast spectrum of wartime afflictions: fear, guilt, loneliness, despair, and a sense of godforsakenness. Lewis’s poetic portrayal mirrors biblical relationships, reminiscent of the struggles between Jacob and God, the dialogues of theodicy between Job and his friends, and the attempts to escape God’s will of Jonah and others. But the most important thing is how Lewis, then an atheist, confronts God.

As one of the “soldier poets,” Lewis believed in the immersive nature of literature, particularly of poetry, viewing it not as an abstract construct but as a lived experience. This perspective led him to employ the poetic form to convey his profound sense of the godforsakenness of Christ. The godforsakenness expressed in Lewis’s poetry, on the loss of his close friend, Paddy Moore, delves into unbearable despair, deep pain, and anger against God, inviting further exploration to fully reconstruct Lewis’s world during this time.

In contrast, Maksym Kryvtsov, unlike Lewis, will not have the opportunity to write a post-war book. His final book, “Poems from the Battlefield,” encapsulates authentic human stories from the war, delving into dreams, hobbies, and future plans, but predominantly unveiling the horrors of war—godforsakenness and death. Maksym, who was killed just days before his thirty-fourth birthday, portrays himself thus: “I love: when you didn’t have water for a long time, but then you were able to drink, and you get so drunk that it hurts to swallow. It’s one of the most pleasant pains. Returning from the war wet, hungry, tired, sitting in the car and listening to someone's music.”[3] Maksym’s book serves as a bridge between those on the battlefield and those in the rear, urging readers not to fear the wide expanse of the battlefield, claiming it as their own. “You must look inside. Don’t be afraid,” wrote Kryvtsov.

The Passion and Godforsakenness

A poignant depiction unfolds in the first passage from Lewis’s poem, capturing a moment of solitude and contemplation. It hints at a shift from the chaos of battle to a realm of a silence so profound and peaceful that it stands in stark contrast to the relentless clamor of warfare—a moment of the silent, that is impossible in battle:

Death in Battle

Open the gates for me,

Open the gates of the peaceful castle, rosy in the West,

In the sweet dim Isle of Apples over

the wide sea's breast,

Open the gates for me!

Sorely pressed have I been

And driven and hurt beyond bearing this summer day,

But the heat and the pain together suddenly fall away,

All’s cool and green.

But a moment agone,

Among men cursing in fight and toiling, blinded I fought,

But the labour passed on a sudden even as a passing thought,

And now-alone![4]

In contrast to Lewis, Kryvtsov embarks on his poetic journey from the heart of death's chaos. He emerges as a transformative force, one who transcends the battleground strewn with the lifeless forms of comrades, breathing life back into the human essence:

Overloading the body ‘V.’

he is now about 50 cm by 50 cm

wrapped in a shroud

sized like a large shoulder bag

the body of ‘D.V.’ spread out

like dough

120 kg over a lifetime and I don't know how much now

‘P.’ with a detached leg

‘A.’ even seemingly whole

men are wrapped in black bags

the last, dreadful darkness

there is not much space in the armored car

you have to touch the bodies

they are warm and soft

like clothes

I look at myself in the mirror

face torn in half

no left hand

the leg is gone

the person disappears

dissipates

like a flower

I want to scream

Stop away!

Stop it!

Enough![5]

The multifaceted experience of Christ’s cry: the raw intensity of “cursing in fight and toiling,” and the desperate plea of “Stop! Stop it! Enough!” These evocative expressions paint a vivid picture of godforsakenness—that moment when grief plunges so deep that even faith and hope seem to waver. Yet, nestled within this existential struggle lies the possibility of kenosis, a self-emptying love we discover through Christ’s ultimate sacrifice.

Biblical commentators highlight Christ’s cry as a powerful expression of human despair and a desperate plea for help from the gathered crowd. This interpretation draws support from the Greek text, where words like βοάω (Mark) and ἀναβοάω (Matthew) signify a loud cry or an anguished outburst. Notably, Christ re-utters this cry at the very moment of his death (Matt 27:50; Mark 15:37; Lk 23:46). This echoes the cry that raised Lazarus from the tomb (Jn 11:43) and mirrors the cry accompanying the angel’s dramatic arrival in the Book of Revelation (Rev 10:3).[6] However, other exegetes offer a distinct perspective. They argue that Christ’s experience of Godforsakenness signifies him taking on not only the burden of “sin for us, who knew no sin” (2 Cor 5:21), but also the very consequence of sin itself: the agonizing separation from God and existence outside God the Father’s divine presence (cf. Gen 1-3). In this interpretation, Christ plunges into the depths of sin without succumbing to it himself. This aligns with the theology of baptism, which starts with being “dead to sin” (Rom 6:2) and culminates in being “born again” (John 3:3). This journey from sin to freedom, from death to life, represents the transformative gift that grants rebirth as a “new creature” in Christ (Gal 6:15).

While forewarning his followers of suffering and persecution (John 14:9), Christ’s own incarnation did not abolish pain. Instead, he became the answer through profound solidarity. In his agony, even he lacked the support of hope for eternity experiencing a temporary eclipse of hope.

This profound despair is captured in Philippians: “Christ Jesus, who, being in the form of God, thought it not robbery to be equal with God; but he emptied himself, and took upon him the form of a servant, and was made in the likeness of men. And being found in human form, he humbled himself, and became obedient unto death, even the death of the cross” (2:6-8). Christ’s cry of godforsakenness was not mere self-pity; it was the surrender of divine privilege. He did not simply humble himself; he embraced suffering to fully understand obedience, becoming the path to salvation for all. This is why his incarnation was intrinsically linked to the Passion (Mark 9:31). It is through Godforsakenness, death, and his descent into Hell that the fullness of human salvation unfolds. This sacrifice, echoing the “death of God,” reveals the depths of his love and redemptive power. In the desperate cry of Godforsakenness the paradox unfolds: the depths of despair become the seed of hope, ignited by the very act of reaching out in prayer. Ultimately, he endured the solitary darkness of “being without God,” facing a test both earthly and divine.

That is why the expression “the person disappears / dissipates / like a flower” resonates so deeply. It encapsulates the harsh reality of dehumanizing individuals, a stark reminder of the brutal suffering Ukrainians swiftly came to understand. In their struggle for survival, they found themselves compelled to embrace the language of hate. Many soldiers had to relinquish their very souls in the pursuit of justice and life. Many of them discovered solitary darkness of “being without God,” as Christ did. Quantifying their sacrifice is challenging, yet it speaks volumes about the inherent value of those who remain in the shadows of their courageous shoulders.

The poems delve deeper, unveiling an escalating sense of solitude: “now-alone,” “anguish,” and “sorrow is blue.” Experience of godforsakenness illuminates the searing isolation we feel in moments of profound grief, doubt, loneliness, and exhaustion. The world seems to recede, and even loved ones feel distant, locked behind the impenetrable doors of our sorrow. That anguished prayer echoes the desperate cry of those who yearn for a divine response in the face of overwhelming silence.[7] This silence of God the Father is particularly agonizing for those who hold deep faith. As Simone Weil pointedly observed, he who has not known God cannot feel his absence.[8] Christ, eternally united with the Father, could only experience this absence through the ultimate kenosis: Godforsakenness, death, and the harrowing of Hell.

The Death and the Shroud

Christ foresaw the impending, arduous death awaiting him, but the gravity of this knowledge seemed to vanish before the events in Gethsemane. His struggle is palpably illustrated through his bloody sweat, tears, and fervent pleas for the passing of the impending trial (cf. Matt 26:36-46; Mark 14:32-52; Luke 22:39-46; John 17). C.S. Lewis poignantly asserts, “He [Christ] could not, with whatever reservation about the Father’s will, have prayed that the cup might pass and simultaneously known that it would not.”[9] The acknowledgment of the inevitability of death on the battlefield becomes increasingly lucid in this context, serving as a stark reminder of the fragility of life in the face of uncertainty, a theme echoed by the poignant words of Victoria Amelina, who fell victim to a Russian missile in Kramatorsk:

Air raid alert all over the country

As if every time they are led to execution

Everyone

And they only aim at one

Mostly the one on the edge

Today it’s not you, the all-clear.

Lewis’s lines, “sorely pressed have I been and driven and hurt beyond bearing this summer day,” and Kryvtsov’s image of men “wrapped in black bags, the last, dreadful darkness,” pierce through time, echoing the very essence of Christ’s agony. Both capture the suffocating despair, the bone-deep ache of mortality, the chilling grip of oblivion that descends upon the dying. The battlefield becomes an altar, the friend’s shroud a mirror reflecting the linen wrapped around Christ by Joseph of Arimathea. Each life extinguished, each soul departing, becomes a silent echo of Christ’s kenosis, an act of radical solidarity with the dying. Hans Urs von Balthasar emphasized that Christ became one with every deceased person in his own tomb.[10] Christ suffers and dies again and again in each person, just as he leads each person out of Hell. This experience of Christ continues his kenosis, embodying solidarity with both the living and the dead.

C.S. Lewis believed that Christ shared in the human experience, even experiencing the despair of seemingly unanswered prayers in the face of agonizing suffering. This, he emphasized, is where Christ’s humanity truly shines, as in a predictable world it is impossible to remain human.[11] Today, one might add that in a totally unpredictable world, maintaining one’s humanity becomes an even more daunting challenge.

The battlefields of Ukraine echo with the cries of the godforsaken, mirroring the ancient tremors of Golgotha. Yet, even amidst the smoke and rubble, whispers of hope linger. Just as Christ descended into Hell, not to condemn, but to liberate, his presence ignites a fierce ember of compassion.

The experience of Christ’s godforsakenness resonates not only through history, but whispers within the cries of every suffering soul. It is the chasm of loneliness carved by injustice, the suffocating emptiness left by betrayal, the chilling dread of impending oblivion. From the beginning of his preaching, Christ emphasizes that suffering, persecution, and sacrifice in the name of God are a blessing, not a punishment (cf. Matt 5-7; Luke 13, 1-5). He later confirmed this on the cross. In the experience of godforsakenness, Christ became open to the point of dying, which was not a known characteristic of God. This is a continuation of solidarity—co-dying.

This improvisation delves deeper into the shared experience of dying, drawing parallels between historical and literary figures and Christ’s sacrifice. It emphasizes the transformative power of his descent into darkness and suggests that even in the midst of suffering, embers of hope remain.

This “dreadful darkness” in Kryvtsov’s poem does not mark the end. Just as the friends on the battlefield perform a sacred act of honoring the fallen, the image holds within it a glimmer of hope. As Joseph’s act foreshadowed the dawn of the Resurrection, so too does the tender care for the fallen soldier hint at a deeper truth. The darkness may descend, but within it, the embers of Christ's love flicker, waiting to be rekindled.

Eventually, the heart of the Christian tradition, pulsating with paradoxes, draws life from the suffering of God, embodied in the Eucharist. The Anaphora prayer resonates not just with Christ’s self-sacrifice, but also with his poignant loneliness: “He gave himself up for the life of the world; he took bread in his holy, pure, and blameless hands; and when he had given thanks and blessed it, and hallowed it, and broken it, he gave it to his holy disciples and apostles.” This breaking of himself, mirroring the breaking of bread (cf. Luke 22:19-20; Mark 14:22-25; Matt 26:26-29), transcends mere ritual or memory. It becomes a tangible symbol of Christ’s broken body, his death. Yet, the Eucharist paradoxically unites Life and Death, offering a hope amidst the desolate darkness of godforsakenness. Through this sacred act, even trauma, pain, suffering, and forsakenness can be transformed and given life.

Home: Resurrection

Throughout history, poets, philosophers, and religious texts have painted evocative imagery of a “home”—the place beyond the trials of this world, where solace and reunion lie in wait. Like a “peaceful castle” offering sanctuary, this home resonates with our deepest yearnings for wholeness, peace, and connection. We all will to go home. We will to go back to all that is opposed to war, as in Kryvtsov’s poem:

The boys will go home

to light and to memory

to the sun and the sea

to leaves and grass

to the wind

to silence

I look in the mirror

and there:

nothing.[12]

Authors like Lewis and Kryvtsov tread carefully when describing this place, contrasting it starkly with the horrors of war and dehumanization:

In the dewy upland places, in the garden of God,

This would atone!

I shall not see

The brutal, crowded faces around me, that in their toil have grown

Into the faces of devils-yea, even as my own—

When I find thee,

O Country of Dreams!

Beyond the tide of the ocean, hidden and sunk away,

Out of the sound of battles, near to the end of day,

Full of dim woods and streams.[13]

“The brutal, crowded faces,” “the faces of devils,” or the “nothing” that appears in the mirror—the wounds of the war, like the wounds that Christ carries after his resurrection, like the wounds that help his disciples identify him, and with which Christ ascended.

С.S. Lewis, finding solace in the belief of resurrection, writes in A Grief Observed that even though we lack a complete understanding of death and afterlife, the promise of reunion offers hope beyond life’s tragedies.[14] Yet, within their hopeful pronouncements, both authors grapple with the lingering shadows of dehumanization, reflecting the stark contrast between this ideal home and the harsh realities of our world.

Another layer of this “home” experience emerges in the anticipation of the Kingdom of Heaven. Scripture portrays Heaven as both a fulfillment of the human heart’s deepest desires and a place of reunion with the divine (Psalm 115:16). However, Scripture also acknowledges the seeming distance and inaccessibility of this realm (Gen 28:10-22). In Heaven, as described in Revelation 21:22, intermediaries, religions, and temples melt away, replaced by a state of blissful contemplation, visio beatifica. This contemplation holds the promise to answer all questions, even those stemming from moments of godforsakenness, dissipating the darkness and revealing the mysteries of the divine.[15]

Yet, alongside this serenity, a sense of longing and incompleteness persists. We cannot quench the inherent human hunger for the divine with fleeting earthly things. As Christ highlights in his dialogue with the Samaritan woman (John 4:5-42), only a connection with the divine truly satiates this yearning. Recognizing this longing becomes a testament to our authentic selves, for our desire for God, love, and truth reflects the echoes of a lost home.

The promise of an eternal home resonating with wholeness and reunion fuels eschatological hope, finding its ultimate expression in Heaven (Isa 65:17; 1 Cor 2:9). Yet, this anticipation is not merely passive. It embodies a potent call, echoed in “Maranatha”—“Come, Lord Jesus!” (Rev 22:20)—urging his swift return. Simultaneously, it acknowledges his already-present grace (1 Cor 16:22). This multifaceted hope assures us that our deepest longings will ultimately be fulfilled, surpassing the limitations of this life and ushering in a reality where even the scars of pain are healed.

This yearning finds powerful expression in the Eucharist, transforming a solitary monologue into a vibrant dialogue with the one who is ever-present (John 8:28). It symbolizes a constant thirst for God, reminding us that we belong to him more deeply than to any other being. The very language of the Eucharistic proskomidia speaks of self-sacrifice, mirroring the ultimate act of love: “to lay down his life for his friends” (John 15:13).

Intriguingly, the Eucharist embodies a paradox. God is both immanently present yet profoundly transcendent, beyond easy comprehension.[16] This creates another layer of hope—embodied and tangible here and now, yet beckoning with an immensity that remains unattainable. This paradox extends even to experiences seemingly distant from divine grace. Hope, though seemingly illogical in the face of death, thrives in spite of it. It exists in opposition to death as the Kingdom of God is present in that which contradicts it, in death. This transformative power is beautifully reinforced by Christ’s ultimate act of offering hope even in the face of despair. On the cross and continually in the Eucharist Christ demonstrates that transformation can take place in the midst of pain and one’s own suffering—but always in the presence of the One who is greater than our heart (1 Jn 3:20). This is the hope of the prayers of all Ukrainians.

In the fleeting weeks before Maksym Kryvtsov’s death, I had the privilege of engaging in a conversation with him, delving into the essence of his poetry. I inquired about the home he had intricately woven into his verses. Maksym wrote immediately: “This is a coffin. The cemetery, somewhere on the outskirts of the native village, next to the church. This is a memory. These are stories. These are dreams. This is the laughter of the boys, which ceaselessly echoes into eternity. It is air, sea, sun, sky.”

In Maksym’s final verses, the foretelling of his own death becomes a profound and poetic proclamation, describing the sinking of bones into the ground, the rusting of a shotgun, and the passing on of possessions and crew to new recruits. Yet, within this inevitability, there is a glimpse of spring, a promise of blossoming violets—a metaphor for hope persisting even amid the cycle of life and death:

will sink into the ground

will form a frame

my shotgun

will rust

the poor

my change of things and crew

will be handed over to new recruits

and rather it is already spring

to finally

to blossom

a violet.

Now, with each bloom of violets, a shared smile emerges on the faces of those who knew Maksym. His words, like fragrant petals in the wind, linger, creating a living memorial in the hearts and memories of those touched by his soul.

[1] C.S. Lewis, Letters to Malcolm: Chiefly on Prayer (London, William Collins Sons & Co. Ltd., Glasgow And Published By Geoffrey Bleі, 1964), 82.

[2] Iya Kiva “The Defense of Humanity,” Krytyka November 2023 (online).

[3] Максим Кривцов, Вірші з бійниці (Львів: Наш формат, 2023), 6-7. [Maksym Kryvtsov, Poems from the Battlefield (Lviv: Nash Format, 2023), 6-7].

[4] C.S. Lewis, Spirit in Bondage (San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1984), 74.

[5] Кривцов, Вірші з бійниці,191.

[6] Див. “βοάω; ἀναβοάω” Frederick William Danker, The Concise Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament (University of Chicago Press, 2009), 23, 73.

[7] Lewis, Letters to Malcom, 61.

[8] Simone Weil, Gravity and grace (London-New York: Routledge, 2002), 27.

[9] Lewis, Letters to Malcom, 63.

[10] H. U. von Balthasar, Mysterium Paschale: the Mystery of Easter (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1990), 141-149.

[11] Lewis, Letters to Malcolm: Chiefly on Prayer, 63.

[12] Кривцов, Вірші з бійниці, 191.

[13] Lewis, Spirit in Bondage, 74.

[14] С.S. Lewis, A Grief Observed (London: Faber & Faber, 1964), 35–6.

[15] Peter Kreeft, Heaven, the heart's deepest longing (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1990), 68–75.

[16] Balthasar, Mysterium Paschale, 95.