Lent is the journey into deeper conformity with Christ who emptied himself unto death and who, risen, is the gift of everlasting life. In Luke 4 Jesus’ self-emptying is presented in his period of temptation in the desert. When encountering this text it is not uncommon for one to focus one’s gaze on the three temptations to which Jesus responds—and for good reason—but the swiftness with which we turn our focus there may prevent us from pondering adequately enough the manner of Jesus’ entry into the desert. But the way the evangelist crafts the beginning of the episode calls for our attention so we may more deeply contemplate Christ. And so I want to look together at just the first two verses of this chapter in hopes of beginning to discover Christ anew as we enter into our Lenten journey.

Filled with the Holy Spirit, Jesus returned from the Jordan

and was led by the Spirit into the desert for forty days,

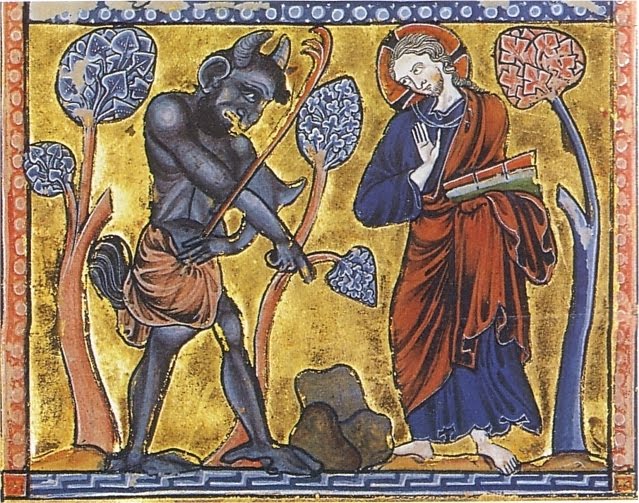

to be tempted by the devil.

He ate nothing during those days,

and when they were over he was hungry. (Luke 4:1–2, NAB)

Let us begin where Jesus began: the River Jordan. In these waters Jesus was baptized at the hands of John. The Holy Spirit came upon him as he waded there and the voice from heaven proclaimed, “You are my beloved Son; with you I am well pleased” (3:22). Luke explicitly connects this to what begins here in the fourth chapter, and so we might think for a moment about the direction in Jesus is moving. He is moving out into the desert, which is to say he is not moving back into the Promised Land. Furthermore, it is the Spirit that leads him this way. This means that Jesus is moving with the Spirit from the waters that Israel once crossed to enter the Promised Land and into the desert Israel traversed to get there. He begins where Israel’s exodus journey ended and goes back into the place of their troubling passage. In Jesus the story of Israel is recapitulated, but according to a descent by which he enters the place of Israel’s disobedience.

We tend to think of the “Temptation in the Desert” as those three memorable temptations that the devil presented to Jesus as the forty days were drawing to a close. But Luke tells us that the forty days were, as a whole, the period of temptation (4:2). The temptations didn’t just come at the end, they weren’t just moments—the desert itself was the place of temptation.

We might ask ourselves, then, ‘So what was the temptation?’ And we might reply that, in sum, the temptation was that of forgetting where he came from and neglecting the longing to return. ‘Where did he come from?’—from that water of promise, from the fullness of the Spirit, from that land of blessing from which he set out. The temptation consists of the offer of making the wilderness into a home, to accommodate himself to it, to leave the bond of the Spirit that leads him there. To be “led by the Spirit” (4:1) is to be led by the love of the Father freely given him (3:22). For him as for Israel the temptation is to separate from that gift of the One who calls by name, but for Jesus alone the mission is to clear that “thicket” (Gn 22:13) of tangled desires remnant in the wilderness from which Israel has come.

But why didn’t he eat anything? Surely, the desert is a generally inhospitable place that offers little, but the text doesn’t say that “he found nothing to eat,” but rather “he ate nothing,” (4:2). This is the active voice—what is passive is the state in which the action of not eating left him: “he was hungry.” Surely something edible could be found in the desert over forty days, so why not eat? Because eating of what the desert provides—what is found there—is to enter into the economy of the desert wilderness. To agree to the terms of the desert is to become one who agrees to the sly beguilement (cf. Gn 3:1) of its “winding ways,” which obscure, confound, and contort the “straight highway” of the Father’s love secured in the Spirit (see Lk 3:4–5; cf. Is 40:3–4). To consume in this wilderness is to become tangled in its web of disobedience, its bramble of deception, thus morphing desire into a fickle thing. And so, in order to bend this thicket of misdirected desires into a “straight highway” of the Lord, “he ate nothing” (Lk 4:3).

In the opening verses of this episode, Luke is presenting the desert to us as the devil’s table. To eat in this place is to accept the terms of the host and conform oneself accordingly. Jesus is certainly denying this hospitality, but that denial is wrapped within the truly fundamental thing: his affirmation of the gift of his Father. Remaining in the Spirit is to receive from the table of Father, to eat what the Father provides, and to be singularly directed in obedience to that will. In this desert that is defined by its inhospitableness to this singular obedience, there is a consequence: “he was hungry” (Lk 4:2). The consequence that he endures passively is an expression of the obedience he wills actively.

The relationship between consuming and accepting the terms of the provider are written into the very grammar of Scripture. Adam and Eve take the fruit the serpent offers and consummate their allegiance to the terms he proposes. Judas Iscariot dips his hand into the bowl with Jesus and consummates the terms of those who offered him silver. Israelites are prohibited from eating the meat of pagan sacrifices because that meat carries with it the terms of those who offer it and of the gods they serve.

If we want to see this enacted even in popular culture, we might look to the pivotal scene of the film The Matrix, in which Cypher seals his betrayal by consuming the meat the agents of deceit offer him. In his case, he knows full well that he is eating more than just a morsel, that in fact his consumption is his consent to the terms of his host. He gives away his freedom and accommodates himself to the tangled web of illusive desires. Had he been faithful, he would have been hungry.

Consuming and consenting to the terms of the provider are linked in the desert of Jesus’ temptation, and because it is so for him it is so for us. As the journey into the desert was for him so our journey into the desert of Lent is for us something deeper and subtler than an endurance contest of repetitive denials. Those denials are expressions of practices in obedience, of eating from the table that nourishes us, and learning to love simply. Being hungry is just what happens to us.