Pater noster, qui es in caelis,

sanctificetur nomen tuum,

adveniat regnum tuum,

fiat voluntas tua,

sicut in caelo, et in terra.

Advent, of course, comes from the Latin word to arrive, and as we begin an Advent unlike any other—my Lord, don’t we know in a hard-won, special way, what it means to wait for things to arrive? Amazon packages; Vaccines; Close calls with asteroids; Monoliths appearing and then disappearing. A New Year. A New Epoch. Arrive already. Let’s get this over with!

The Our Father, as it were, contains the whole season of Advent within it, both in word and spirit. “Adveniat regnum tuum,” Thy kingdom come, as we say in our King James inflected English, but the prayer is asking something much more direct. “Oh Lord, may your kingdom finally arrive.” The middle of the “triple commands” that make up the first half of the Lord’s Prayer has a special, sweet, and even plaintive impatience that we often miss. We are begging you, Lord, arrive.

People often forget this, that we are making demands—of both earth and heaven—whenever we pray at all, but especially so with this prayer. The name of God? May it be sanctified. And God’s will? Make it happen and make it snappy. But of course, on our mind this season is the arrival of a kingdom long promised. Thus it is in Advent, we get bossy, we make the same kind of demands, but this time, not with those things which speak or show or sound of God, but a plea to the Almighty Himself: come Lord Jesus, come.

Isaiah is the “book of the month” for Advent, and if you read it long enough, no wonder why you might get a little bossy—and testy too. There are not enough cities in the world for the Lord to reduce to smoldering ash in those pages, though we modern Christians try our damnedest to filet the brimstone Prophet so as only to leave the “Is it I, Lord?” in our hymns.

The truth of the matter is this: before God sees fit to show himself as the babe of Bethlehem, He manifests first as an unquenchable torch. Every time a Christian north of the equator sees purple and the time honored “Starbucks-is-switching-from-pumpkin-spice-to-peppermint-mocha” sign of the times, our thoughts should turn not first to candy canes, or even the pregnant Mary, but to ruins of metropolises now populated by wandering wild asses (Isa 32:14). Rather than jingle bells, mad and meandering braying should be the soundtrack of the season.

All this is to say: it is no wonder we avoid the “bossy” nature of this season, where we up the ante of Christ’s own prayer he taught us, and with laser focus reduce it to the simpler mantra of “come Lord Jesus, come.” If your nose does not know the sulphury smell of Isaiah’s prose, you have all the time in the world to be lulled asleep by glossy episodes of our hyper-Dickens nostalgia industry.

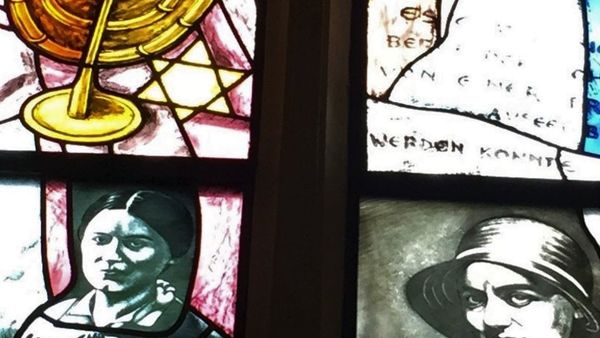

If you can avoid (as we seem to at all costs) the glowering eyes of the man whose very lips were purged with a heavenly burning coal, you do not want Christ to come now—for goodness sake, we have only made it through our first helping of ham, and this year—well its been a doozy all on its own.

No one needs told that the world has plans quite different from Isaiah. We need very little cajoling to submit to the Hallmark regimen of fattening up and forgetting, not only our cares, our woes, this entire cursed year, but also the essential fact that we are awaiting a savior. This is old news. We have all heard the traditional harangue: Remember the reason for the season. Tale as old as time.

One is tempted to say: Can’t we just be lazy this time around? It’s 2020, and we still even pulled out an Advent calendar, and look man, we are sick of calendars at this point. We have been stuck inside for months, the passing of each multi-squared page meaning less and less as this wretched year goes on and the calendar laughs at us. Do we really need a fire-inflected sermon at this point? Is not the pestilence enough? Have we not earned the ability to enjoy our sweets-laden carb loading in peace and without shame?

Let me say this all in another way, because the fire and brimstone are actually not the point. As anti-climatic as it sounds, it is the damned donkeys, hooves kicking the dying embers, that we must remember to call to mind. The overlooked beasts wandering through the wasted cities? That is the critical image we must refuse to forget—even in the midst of our hyperglycemic rising-blood-sugar-induced haze.

A God who is angry and punishes his errant people is not all that exciting or special among the gods. One who pulls a guilt trip on you for self-medicating with high fructose corn syrup delivery morsels in a year like this is hardly worth our time to consider. But one who turns over His prize jewel, the city of his altar, Jerusalem itself, to the wild jackasses of the world—jackasses like me and mine, for instance? Now that is a surprising and different manner altogether.

You see, what is most inexplicable is not that the more comfortable Christians are, the more difficult it is for them to understand the expectant nature of Advent. We all know this instinctively. We cram more ham down our gullets by mid-December than anyone but the Iowa pork industry would be happy to admit. And it is not confounding in any way that we shy away from the warnings of Isaiah—only liars would hear the sparks of those flaming lips and refuse at least an interior tremble. The hands of the One who is Justice itself are not any less terrible though they come to us first as tiny infant fingers reaching out to his mother. Let us be honest—children are terrifying on their own, both in the positive and negative connotations of the word. That one such Child also came as God himself to set things right only puts this fact in stark relief.

What is actually inexplicable is that God himself has taught us, has commanded us, to make such heady demands of him, and goes so far as to cement the prospect of our salvation in our insistence to boss the Deity around. To put it another way: we do not simply shrink from demanding, Come Lord Jesus, because we are fat and lazy. The inverse is even more true—we have become fat and lazy because we have stopped making demands of the Lord that he come. We have lost the nerve requisite to accept the inestimable gift of being wrested from the Kingdom of Satan and the Dominion of Death. That we are weak-willed when tempted by candy and cake and eggnog is not worth mentioning. That our wills waver before the command to command, when confronted with the task to make demands of God he himself demands we make? This is our undoing.

Beyond self-loathing or misanthropic tendencies of the West, beyond claims about the nihilistic underpinnings of consumerism, beyond the soul-crushing weight of modern regimes of power, Advent calls out our most essential cowardice, the existential fainting before the one thing necessary. The point is not the philosophical or metaphysical one we conjure. It is much simpler than that.

Literally, for the Love of God, have some ambition. Advent demands it of you. This marvelous story of Jerusalem and the Messiah and the chosen people and everything else—it was seemingly not about you at all. At least, that is, not at first, and not for most of us. It had gone on for ages, this tale of the Hebrew People and their God, and for most of you reading this, descendants of Gentile Pagans that you are, you were often an afterthought at best, or even the more so, the villains depending on which Minor Prophet you asked. It was not expected that things would end up well for you and yours. Your entrance in the third act of the play was a surprise to nearly everyone.

And yet, God knew, and was patient, both with his people, and with the wild asses too stubborn to find their way into the barns of their master. He waited, and waits, and who knows how long the Lord will tarry henceforth. But at this appointed time, here you are, a meandering jackass in the ruins of God’s chosen jewel. For reasons you may never understand, in the smoldering ruins of his prize-possession, He has handed his lovely bride over to you. Your time has arrived. Make the demand. This Advent do not refuse to look God himself straight in the eye, and say with the Ancient Church: Come Lord Jesus, Come. Bray away.