It is the first week of Advent, and I am waiting for Jesus’s flesh. That is not all I am waiting for, but it is the central thing, the thing without which I would not be waiting for anything else. This means that Advent is a fleshly season first and last because the direct intentional object of all the waiting that goes on in it is flesh, and not just any flesh, but the flesh of a male Jew who, rather more than two millennia ago, was conceived, birthed, suckled, catechized, inspired, baptized, tortured, killed, raised and taken up to heaven. More than that; but at least that.

One aspect of my waiting is strictly memorial. I am waiting to be able to remember Jesus’s natal flesh, the flesh conceived in Mary’s womb, active in Galilee and Jerusalem, and crucified at Golgotha. That flesh is no longer with us, and cannot be. I have never seen it or touched it or tasted it, and I never will. Neither will you. With respect to that flesh, what I am waiting for is to remember it, to assemble the fact of it in my mind’s eye in the company of others doing the same. That remembering will reach its culmination, I hope, at the Mass that turns Advent over into Christmas.

But that remembering is not much different from what I do when I think about Augustine or Pascal. I never saw them in the flesh, and while I have seen Pascal’s death-mask, and a picture that may show me something of what Augustine looked like, their natal flesh is gone, irretrievably. If I am ever lucky enough to see and touch them in the flesh, it will not be their natal flesh. No, it will be their resurrected flesh, which will be theirs but transfigured, theirs but not mortal, theirs but (perhaps) unrecognizable to those who knew their natal flesh. Just so with Jesus: what I will see and embrace, should I be so lucky, is his ascended flesh, which is lineally and causally related to his natal flesh but in important ways different from it.

When I think about and progressively remember Jesus’s natal flesh during Advent, I do not form any image of it. I do not think of particular features, a particular skin tone or color of eyes, a particular height or timbre of voice, a particular smell of sweat or color of blood. I do not know what he looked like, and do not care to. The New Testament shows no interest whatever in this matter; and while we may have images of his natal flesh (Veronica’s vera icona, not made with hands; the Shroud of Turin), these are esoteric exotica of which Christians have no need. What counts, for us, about his natal flesh is that it was, not what it was like.

That is why remembering Mary, putting her place in the story of our salvation together in our heads again, is as important, during Advent, as remembering Jesus’s natal flesh, and in some ways more so. Mary is the guarantee of what counts, which is that Jesus was enfleshed (incarnate) as a Jewish man of the line of David; that is what we need to know, and that is what we move toward full recall of as Advent progresses. It is why so much time is spent in Advent on Mary’s womb, and what was going on in it.

It is clear, of course, that Christians have spent a good deal of time and energy in imagining and picturing Jesus’s natal flesh. I rather wish they had not. I do not. It seems, to me, unseemly to do so.

I do not want and will never have Jesus’s natal flesh. What I do want, and can have, in Advent as much or as little as at any other time, is his Eucharistic flesh, dissolving rapturously on my tongue. But there is nothing particularly Adventian about that; its presence and availability is a feature of the Christian life. I am not waiting for that: it is here. I am fed with it during Advent as elsewhen.

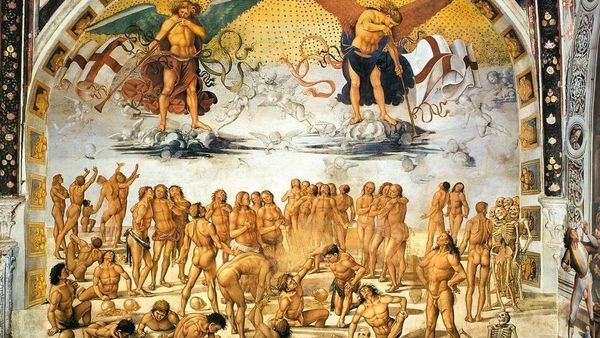

But there is another kind of Jesus-flesh that Advent encourages me to wait and pant for, to attend to and hope for, and even to imagine and yearn, haptically, for. That is Jesus’s ascended flesh. Many of the Advent lections turn my flesh altogether (eyes, ears, nose, skin, tongue) toward the Jesus who will come on the clouds, in the flesh, to wind things up and to judge and to embrace his beloveds—which, so far as I can tell, means all of us, everyone, without exception. (Who among us is not his beloved? Universalism is the grammar of Christianity, even though most Christians have not thought so.) The life of the world to come is a fleshly life, and the central fleshly fact in it, that around which all of it revolves, is the ascended flesh of my Lord. I anticipate that embrace; Advent encourages me in that by holding it before me as promise and threat.

But why threat? Why not just promise? Is it not what I want? Yes, of course, but the threat, a matter of fleshly trembling, is because I might not be ready to return the kiss—O, kiss me with the kisses of your mouth, we are required to ask, to demand, to plead, and yes, I would like that, I want that: I want Jesus’s kisses, and they will not be metaphorical, fleshless, dry; no, they will be warm and fleshly and rhapsodic and . . . well, I would need to be Shakespeare or Donne to do justice to this topic, and I am far from having those capacities. But the thought and the hope make me tremble, and Advent, in its twining of darkness and light, its encouragement of tenebrous hopes, encourages me in that trembling because the season shows me what I already know, which is that I am not ready. Jesus’s kisses, Jesus’s caresses, would scald and scorch and scarify me as I am now. I am insufficiently adorned, insufficiently clean, insufficiently anointed, to be able to welcome them. And so I tremble. I tremble in the flesh, at the thought of what, in the flesh, will be offered me by Jesus’s ascended flesh.

I take trouble, here below, to make my natal flesh pleasing to my beloved, to wash it and sweeten it and anoint it and make it like honey for her. I need to do that, too, but more, so much more, to make my risen flesh pleasing to my Lord’s flesh, to make my lips capable of returning his kiss. Advent makes me attend to that preparation, and in attending to it I see that, in fact, it is not something I can do—it is, rather, something that will be done to and for me, in the flesh, and by the flesh of Jesus, if I let it; all I can do about it is accept it or turn my face from it, and in seeing that, and seeing that I do turn my face from what faces it, I have a foretaste of purgatory. The fabric of Advent as a time of waiting is, indeed, purgatorial in its every thread. How could it be otherwise.

EDITORIAL NOTE: This Advent meditation grows out of the recently published Christian Flesh (Stanford, 2018).