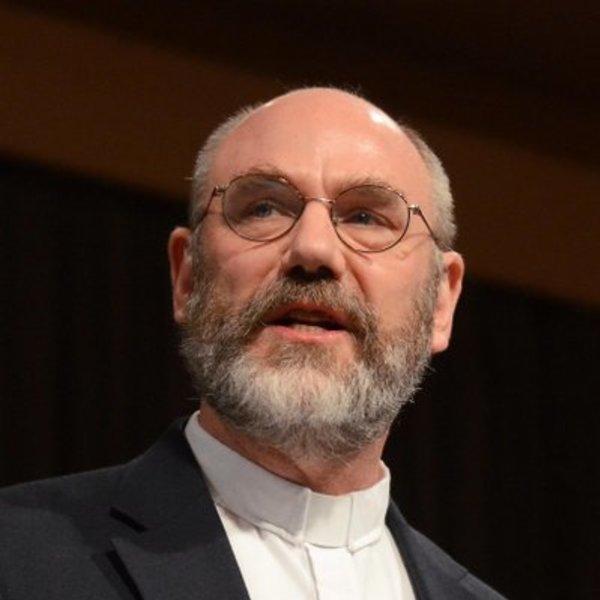

Even among Reformed Protestants, John Williamson Nevin (1803-1886) has been a half-forgotten figure, more obscure than his colleague, the church historian Philip Schaff. Together, Nevin and Schaff formulated what became known as the “Mercersburg Theology,” named for its base of operations, Mercersburg Seminary in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. A “Reformed Catholic” movement, Mercersburg took its stand against populist revivalism, rationalistic theology, and sectarian practice. Positively, Nevin and Schaff attempted to inject tradition, sacramentality and liturgy, and a catholic spirit into the American Reformed churches. Nevin castigated revivalism in his tract on the Anxious Bench,[1] and The Mystical Presence[2] sparked a vigorous debate on the real presence with Princeton’s Charles Hodge. For their efforts, Nevin and Schaff accused of “Romanizing” tendencies.

Mercersburg has been enjoying renewed attention of late. D. G. Hart published an excellent biography of Nevin in 2005,[3] and several volumes of the Mercersburg Theology Study Series have appeared since the series was launched in 2012. Last year, Cascade published a Companion to Mercersburg, edited by William Evans.[4]

The renewed attention to Mercersburg has a more than historical interest. Nevin and Schaff make substantive contributions to contemporary Protestant theology, and some of their proposals have ecumenical scope. Nevin’s vision of catholicity, for instance, overlaps in important ways with the integralist vision of the nouvelle theologie and recent Catholic political thinkers. He qualifies as a Protestant integralist.

I. Catholicism

Nevin’s view of catholicity is most fully developed in an 1851 essay in the Mercersburg Review on “Catholicism.”[5] Nevin distinguishes two ways of understanding the church’s universality—as “all” or as “whole.” Considered as “all,” the church catholic is an agglomeration of congregations prior to the catholic church itself. This is an “abstract” understanding of catholicity, since the universality in view refers to a totality that “exists only in the mind” (3). Catholicity understood as “whole,” however, is concrete and real, and prior to the existence of individual instances. “All” presents a mechanistic picture of catholicity; “whole” an “organic” one (3).

Idealist as he is, Nevin prefers “whole” to “all.”[6] But what is that whole the church claims as its range of concern? Nevin glancingly refers to a cosmic dimension; Christianity embraces the whole of creation. More usually, he narrows his focus to the human whole. To say that the church is “catholic” is to say that it has “universal humanity” in its scope.

To Nevin, this has two dimensions. First, the church or Christianity is as expansive as human existence (or the cosmos), leaving nothing outside its range of interest or its claims. Second, the church or Christianity is the completion of this human or cosmic whole; that is, Christianity brings the cosmos and especially humanity to perfection. Whatever there is of human existence is taken up by Christianity to a higher level. As Nevin says, the church “has a call to possess the world, and it is urged continually by its own constitution to fulfill this call.” The church carries out her mission on the premise that “it is the only absolutely true and normal form of man’s life, and so of right should, and of necessity also must, come to be universally acknowledged and obeyed” (6).

Nevin expands on catholicity-as-whole by distinguishing the extensive/outer from an intensive/inner dimension of catholicity. The former is better known: The church is catholic because she includes people from every era of history and from every corner of the globe. She is catholic as she carries out her evangelistic mission throughout the world. For Nevin, extensive catholicity has a Christological root. Jesus is Lord of all, and intends to take possession (Psalm 2) of all. Christianity cannot cede any territory to another religion, never accept that a particular territory is permanently and unchangeably “profane.” The church’s mission will not be finished until she “possesses all,” because Jesus’s purpose is “the conversion of nations.”

Catholicity has an intensive/inner dimension as well. Just as salvation brings an individual to perfect holiness, so the whole of human existence must be renewed and sanctified from within. Social institutions like the family and state and cultural pursuits like art, science, and philosophy are inherent in human existence as such. This range of human activity is a mission field:

Humanity includes in its general organization certain orders and spheres of moral existence, that can never be sundered from its idea without over throwing it altogether; they enter with essential necessity into its constitution, and are full as much part and parcel of it all the world over as the bones and sinews that go to make up the body of the outward man. The family for instance and the state, with the various domestic and civil relations that grow out of them, are not to be considered factitious or accidental institutions in any way, continued for the use of man's life from abroad and brought near to it only in an outward manner. They belong inherently to it; it can have no right or normal character without them; and any want of perfection in them, must even be to the same extent a want of perfection in the life itself as human, in which they are comprehended. So again the moral nature of man includes in its very conception the idea of art, the idea of science, the idea of business and trade (10).

To say that Christianity is “catholic” thus means that she presses Jesus’s claims to every dimension of human life. The church cannot be content to allow any area of life to be permanently “secular,” any more than it can leave some piece of geography pagan: “Nothing really human can be counted legitimately beyond its scope.” Nothing can be regarded as profane “in the sense of an inward and abiding contrariety between it and the sacredness of religion” (11). As Nevin writes,

It is full as needful for the complete and final triumph of the gospel among men, that it should subdue the arts, music, painting, sculpture, poetry, etc., to its sceptre, and fill them with its spirit as that it should conquer in similar style the tribes of Africa or the islands of the South Sea. Every region of science, as it belongs to man's nature, belongs also to the empire of Christ; and this can never be complete, as long as any such region may remain unoccupied by its power . . . We might as soon dream of a like exclusion towards the empire of China; for it is hard to see surely how the idea of humanity would suffer a more serious truncation by this, than by being doomed to fall short of its own proper actualization the other way (12-13).

Appealing to the parable of leaven, he argues that all of humanity’s moral life is to be permeated by the gospel’s influence. Christianity “must take up his nature into itself intensively, as leaven works itself into the whole measure of meal in which it is hid, in order that it may be truly commensurate with the full volume of his being outwardly considered” (9).

For Americans, this has some unsettling political implications. In Nevin’s view, the American system of church-state relation, as it had developed by Nevin’s lifetime (and certainly since), is inconsistent with the church’s claim to catholicity:

It is coming to seem indeed a sort of moral truism, too plain for even children or fools to call in question, that the total disruption of Church and State, involving the full independence of all political interests over against the authority of the new constitution of things brought to pass in Christ, is the only order that can at all deserve to be respected as rational, or that may be taken as at all answerable to man's nature and God's will . . . what a conception is that of Christianity, which excludes from its organic jurisdiction the broad vast conception of the Commonwealth or State . . . The imagination that the last answer to the great question of the right relation of the Church to the State, is to be found in any theory by which the one is set completely on the outside of the other must be counted essentially antichristian (14).

The rhetoric is nineteenth-century American triumphal, but the logic of the argument is impeccable. The church’s mission cannot stop at any geographic boundary. How can she stop at the equally artificial boundaries that marks out a “political” realm? If the church is catholic, it cannot be content with current interpretations of the religion clause of the First Amendment.

II. Catholic Faith, Catholic Church?

Nevin’s treatment of catholicity is dogged by an ambiguity. At times, he speaks of the catholicity of “Christianity,” while at other times he attributes catholicity to the church. The ambiguity enables him to keep his distance from Roman Catholicity, which in Nevin’s view pursued an extensively and intensively catholic mission by means of violent imposition rather than by witness and service. Nevin is not a Romanist because he does not think the “church” claims all of human existence as its domain. Only “Christianity” does.[7]

That leaves a set of questions dangling: What role does the church as church play in the fulfillment of this intensive mission? What is the connection between the church’s ministry of Word and Sacrament and Christianity’s leavening of culture? Nevin’s answers are not entirely clear.

Though Nevin leaves the answer to this question ambiguous, his treatment of catholicity is intertwined with an insistence that the church is a public, visible mediation of the presence and grace of Christ to the world. This was at the heart of his battle with Charles Hodge. The debate was overtly concerned with the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist, but it was in reality a more basic battle over theological vision and the meaning of the church. It was a struggle over whether “Christianity” or the church is catholic.

Hodge’s Systematic Theology contains no section on ecclesiology. The oversight was not deliberate. Hodge intended to add a fourth volume dealing with the doctrine of the church, but did not live to complete the task. Yet it tells us something about Hodge’s ecclesial vision that he could include a long section on sacramental theology in volume 3 without developing an overt doctrine of the church.

His ecclesiological introduction to Discussions in Church Polity indicates some of the reasons behind his separation of sacramental theology from ecclesiology.[8] Following one thread of the Reformed tradition, Hodge insisted the church could not be defined as a visible society. Such a definition does not, Hodge argued, fit the biblical terminology or the biblical descriptions of the church. When the New Testament speaks of the church, it speaks of a communion of holy people, called and justified. Since every visible body of believers includes some who are unholy and unbelieving, the New Testament writers cannot be speaking of a visible body. They must be speaking of the invisible church of the elect, which is not coterminous with any historical expression of the church.

Hodge argues that this is the position of the creed, which defines the church as a “communion of saints”:

The conception of the Church as the communion of saints, does not include the idea of any external organization. The bond of union may be spiritual. There may be communion without external organized union. The Church, therefore, according to this view, is not essentially a visible society; it is not a corporation which ceases to exist if the eternal bond of union be dissolved. It may be proper that such union should exist; it may be true that it has always existed; but it is not necessary. The Church, as such, is not a visible society (5).

Hodge acknowledges the church is visible in a number of respects. Believers are visible and bodily, not spirits or angels, and so the communion of saints is visible in the saints. Saints produce good works, which “manifest their faith.” Because the saints have been effectually called and separated from the world, they are “animated by a different spirit, and are distinguished by a different life.” Perhaps most importantly,

The true Church is visible in the external Church, just as the soul is visible in the body. That is, as by the means of the body we know that the soul is there, so by means of the external Church, we know where the true Church is . . . the external Church, as embracing all who profess the true religion—with their various organizations, their confessions of the truth, their temples, and their Christian worship—make it apparent that the true Church, the Body of Christ, exists, and where it is (56-7).

Hodge does not ignore the church as a visible reality, but he considers it a great error to identify that visible organization with the church itself. To confuse visible and invisible is as wrong-headed as to confuse body and soul. Hodge dismisses Roman Catholic and high Anglican ecclesiologies as “Ritualist,” since they identify the true church as those who participate in sacraments and live in submission to some form of prelacy.

Hodge of course confesses that the church is catholic: “It is catholic only as it is one.” Its catholicity is a function of its unity, and its unity is not visible and institutional but spiritual. He contrasts his position to Roman Catholic catholicity, which “depends on subjection to one visible head, to one supreme governing tribunal,” with the catholicity of a church whose unity “arises from union with Christ and the indwelling of his Spirit.” In Hodge’s ecclesiology, “all who are thus united to him, are members of his Church, no matter what their external ecclesiastical connections may be, or whether they sustain any such relations at all” are part of the catholic church. The visible church is also catholic, since it includes “all who profess such union by professing to receive his doctrines and obey his laws, constitute the professing or visible Church.” Hodge insists that:

The evangelical are the most truly catholic, because, embracing in their definition of the Church all who profess the true religion, they include a far wider range in the Church catholic, than those who confine their fellowship to those who adopt the same form of government, or are subject to the same visible head (44).

On Hodge’s understanding, the church’s catholicity must be limited to geographic and temporal extension. The church cannot be intensively catholic without turning Romanist and ritualist. It is only Christianity—a looser reality than “church” —that possesses an intensive catholicity.

Nevin, for his part, hardly fits the caricature of the “ritualist,” though Hodge considered him such. For Nevin, the notion that the church was essentially invisible was a denial of the basic confession of Christian faith, that the Second Person of the Trinity was made flesh. Nevin considered the church an extension through time and space of the mystical presence of Christ. As such, she can be no more disembodied than he can.

Nevin believed the church is a mediator of grace, through sacraments as through its other institutions and practices. As he wrote, “The idea of the Church, as thus standing between Christ and single Christians, implies of necessity visible organization, common worship, a regular public ministry and ritual, and to crown all, especially grace bearing sacraments.”[9] As K. H. Steeper summarizes:

Mercersburg Theology is a churchly and sacramental system where the church is truly the body and presence of Christ in the midst of history. For this reason the church is seen as both divine and human. It is a mediator of God’s grace through the Word preached and the Sacraments that serve as “seals” for the spiritual mysteries that they present. Finally, its liturgy is Christocentric and Incarnational as well, moving away again from the ‘subjective' and private judgment (48).

On this understanding, the church’s specific ministries of Word and Sacrament appear to be essential to intensive catholicity. It is not enough to say that “Christianity” or “Christians” are the leaven that penetrates and transforms all of human life, bringing it all to its perfection. Christians can be leaven only as members of the mystical body, the incarnation extended in the church. Nevin’s vision is not that the church directly dominates politics, arts, philosophy, or other areas of culture. Yet, without the visible, public manifestation of Christ’s presence in the church, those areas of culture will not be leavened and brought to their full human wholeness.

III. Conclusion

I believe Nevin is correct: A church catholic is a church with a catholic mission. To use the current Evangelical lingo, a catholic church is necessarily a missional church, not only extensively but intensively. The catholic church exists to evangelize politics, evangelize law, the arts, entertainment, business, philosophy, and all and everything else. If, as the Dutch theologian Abraham Kuyper said, there is no square inch of this world of which Jesus does not say “It is mine!” there is no square inch of human experience that Jesus does not claim, where Jesus does not send his church. As Nevin put it,

The spirit of missions, wherever it prevails, bears testimony to the catholicity of Christianity, and rests on the assumption that it is the only absolutely true and normal form of man's life, and so of right should, and of necessity also at last must, come to be universally acknowledged and obeyed (6).

A catholic church has a public, political, cultural presence. Her mission is not merely a mission to individuals. She has a cultural mission, and that means she must intervene, directly or indirectly, into the cultural issues of the time, shining the light of God’s glory into shadowy nooks and crannies. As the scattered church, in the form of individual members in their various vocations, the church brings the gospel to bear on business, political, cultural pursuits. This is part of her catholic identity. A church that fails to do this, that limits herself to saving souls, is not a fully catholic church. As “institution,” the church must equip her members to be the leaven of society, forming them by Word and Sacrament. In some cases, the church must directly address cultural concerns, speaking the Word of God into the confusions of the times.

This is the catholicity that serves as a mark of the church and distinguishes the church from all other societies and corporations. One might imagine a world-wide empire, universal in extent. But such a society could not make the totalizing claims the church makes without becoming totalitarian. It could not demand that everything be remade in accord with its imperial demands. But Jesus is in fact the world emperor. He is a catholic king. He claims not only all the earth, the katholike of geographic extent, but the katholike of human existence. Since the church mediates the presence of Jesus in the world by the Spirit, she too, in her various activities and aspirations, presses the claims of Jesus on the world.

[1] The Anxious Bench (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2000).

[2] See The Mystical Presence (Mercersburg Theology Study Series #1; Linden DeBie, ed.; Bradford Littlejohn, gen. ed.; Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2012).

[3] Hart, John Williamson Nevin: High Church Calvinist (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R Publishing, 2005).

[4] Evans, ed., A Companion to the Mercersburg Theology: Evangelical Catholicism in the Mid-Nineteenth Century (Eugene, OR: Cascade, 2019).

[5] Nevin, “Catholicism,” Mercersburg Review 3 (1851) 1-26. Page numbers for this essay appear parenthetically in the text.

[6] Nevin writes, “The true universality of Christ’s kingdom is organic and concrete. It has a real historical existence in the world in and through the parts of which it is composed; while yet it is not in any way the sum simply or result of these, as though they could have a separate existence beyond and before the general fact; but rather it must be regarded as going before them in the order of actual being, as underlying them at every point, and as comprehending them always in its more ample range. It is the whole, in virtue of which only the parts entering into its constitution can have any real subsistence as parts, whether taken collectively or single” (4). This, he claims, is “undoubtedly” what the early church meant when it confessed the church as “catholic.” As a philosophical point, Nevin’s argument is questionable: Why should the whole be prior to the parts, if neither exists without the other. Why can they not be equiprimordial? Nevin is more convincing when he describes the ecclesial “whole” Christologically: Christ is the concrete whole of which the body’s members are parts. Taken Christologically, the whole precedes the parts in every respect, and the parts of utterly dependent on the whole.

[7] The same ambiguity appears in an extraordinary essay by the nineteenth-century Dutch Reformed theologian, Herman Bavinck, translated into English by John Bolt, “The Catholicity of Christianity and the Church,” Calvin Theological Journal 27 (1992) 220-251. Bavinck’s essay was first published in Dutch in 1888, and was translated into English by John Bolt.

[8] Hodge, Discussions in Church Polity (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1878). Page references are included parenthetically in the text above.

[9] Quoted in K.H. Steeper, Between Mercersburg and Oxford: The Ecclesiology of John Williamson Nevin (M.A. Thesis, Western University, Ontario, 2014) 47.