My brethren, show no partiality as you hold the faith of our Lord Jesus Christ, the Lord of glory. For if a man with gold rings and in fine clothing comes into your assembly, and a poor man in shabby clothing also comes in, and you pay attention to the one who wears the fine clothing and say, “Have a seat here, please,” while you say to the poor man, “Stand there,” or, “Sit at my feet,” have you not made distinctions among yourselves, and become judges with evil thoughts? . . . Has not God chosen those who are poor in the world to be rich in faith and heirs of the kingdom which he has promised to those who love him? But you have dishonored the poor man. Is it not the rich who oppress you, is it not they who drag you into court . . . If you really fulfill the royal law, according to the scripture, “You shall love your neighbor as yourself,” you do well. But if you show partiality, you commit sin, and are convicted by the law as transgressors. For whoever keeps the whole law but fails in one point has become guilty of all of it. (Jas 2:1–10)

The Eucharist is the source and summit of our faith. For many of us who are a few generations away from immigrant status, our parishes needn’t worry about preferring the rich to the poor at our Eucharistic table. The poor, or, to borrow a term used more broadly by Romero, the “protagonists of history,” simply aren’t there.

The absence of the protagonists of history at our Eucharistic table is a crisis not only for us, but for our children. If you have kids, you are probably worried (or you should be) that they may not be Catholic when they leave you.

As educated Catholics, we all to try to help our children to have an adequate ability to think clearly, to analyze, and to gain an accurate understanding of the world and of our faith. My family spends countless moments discussing events, ideas, and our faith. Each day presents opportunities for intellectual formation. We value abstract reasoning. Most educated Catholics conceptualize passing on the faith as participating in the sacraments and passing on the truths of the faith.

The truths of the faith. To hold something to be true, we tend to think that we have an understanding that we can articulate in words. Almost everything about our culture encourages us to think of truth as an idea, a concept. Our educational culture since the Enlightenment encourages verbal and written articulation. Outside of encouraging weekly Mass and some service work, we think of passing on the truths of the Catholic faith as passing on a correct conceptual understanding. A dear family friend, Fr. Joe, calls it Catholicism as Philosophy.

I used to think that concepts were the primary way of passing on the faith. As a youth minister, I tutored a high school senior who had missed her Confirmation. I worked very hard to give what I thought were amazing explications of the faith. I was, after all, a theology buff and trained at Notre Dame over many summer courses. Laura’s mom affirmed my excellent teaching when she said, “Laura said she really loved your class.” I was pumped. My hard work at conveying the faith was not only paying off, I was being recognized. Until she finished her thought: “It wasn’t so much what you taught, but who you are.” I was crushed. How could this student not see my amazing explanations as the crowning achievement of her instruction?! Apparently the fact that we had foster kids and such was what helped her to become Catholic. In other words, our service to the poor was essential to passing on the faith.

At a Sunday gathering of some very thoughtful Catholic friends, I stood, hands in pockets, with a fellow dad on the porch and pondered the best way to help our kids stay Catholic. “I change my mind every three days about where to send my kids to school,” Phil said through his glass of good Wisconsin brew.

Catholic schools frequently replicate the forms of public schools, treating faith as one additional subject matter among many. Other Catholic schools that boldly set themselves apart in support of a self-proclaimed orthodoxy sometimes confuse and co-mingle Church teaching with partisan politics and revisionist histories, falling far short of modelling thinking with the Church. Public schools occupy many hours a day, cannot speak of God, and the absence is deafening. Finding adults who model the beauty, nuance, joy, and adventure of the faith is very difficult.

Further impeding our kids’ struggles, Phil and I mulled, is the reality that many of our schools, houses, and Eucharistic celebrations occur in parish neighborhoods without poor people, and without any kind of racial diversity. In my county of Dane and my hometown of Madison, the sort of Berkley of the Midwest, we are further injured by being a leader in racial disparities. Along every measure, we are a national leader in gaps between African Americans and white people.

Phil and I agreed that we cannot hope to help our children to stay Catholic when they are cut off from the people with whom Jesus is closest. It is very clear that our Lord is most present in the protagonists of history: ‘When I was naked, you clothed me’ (cf. Mt 25:36). If Jesus is closest to those in need, and our only connection with people occurs across the ocean of a soup kitchen pot, we are not close to Jesus. We cannot find our Lord when we are absent from him, and he is with the poor.

In the end, Phil and I agreed that regular, face to face work with the protagonists of history will keep our kids Catholic. I shared my confidence that Eucharist in union with these protagonists is a lasting experience of Jesus that will prove salvific, because I recently saw my daughter come back to the Church through worthily celebrated Eucharist.

Kateri chose not to be confirmed in high school. She was blessed to work at Casa Hogar, an orphanage founded and supported by the Diocese of LaCrosse, WI. Kateri found that daily Eucharist with the orphans opened her up to a deeper relationship with Jesus and his Body, the Church, in a profound way.

In her talk to the children upon her Confirmation at the Easter Vigil in Casa Hogar, she explained beautifully the truth that the Eucharist is to be found in being at the Lord’s table as one who recognizes one’s own poverty, united with the protagonists of history. This action of grace in a worthily celebrated Eucharist is best heard in her stark and simple words to the children at her Confirmation, translated to English:

For a long time, Confirmation was not important in my life. I did receive my first Communion, the Sacrament of Reconciliation, and I went to Mass every Sunday.But a little bit later, when I started to have a stronger prayer life, a very personal relationship with God—this is when I started to understand the importance of this commitment in my life, the confirmation of my faith. This is a commitment to Christ and to the community.

I wanted to be Catholic all my life and I also had the good fortune of having parents that taught me the values of God, of the Church, and they did all they could to motivate me to have a relationship with the Lord.

When I left home at eighteen years old I realized that now this was my decision. Whether I would continue with it. It was hard because I had a lot of things to do, a lot of responsibilities and sometimes I asked myself: why do I go to Mass? I don't have much time, so why do I have to go to church?

But some time later, one day when I was at church with my family I suddenly understood that Mass was not just something for me. The Church is a community, Christ is present in his whole Body, in the whole community. I used to understand this logically but never emotionally.

That’s when I started my preparation for Confirmation. In order to accept the responsibility as a member of the Church so that I can say, “I’m committed.”

The time I spent in this house has been a great support in my preparation. I was able to grow. When I see the commitment you have in this community, the support you give each other, the love you share, I see Christ.

This is my promise today: to participate in the Church, the living Body of our Lord Jesus Christ.

Our kids can know Jesus and their own poverty as they struggle with frequent, face-to-face relationships as an equal in poverty of spirit with the protagonists of history. When our kids realize we are equally poor, and that we must continue the Eucharist through the sharing of our very lives with our brethren, our kids will meet and stay with Jesus.

Our children will not be impressed with our understanding of concepts. Our notions cannot survive the pressure of reality. It is clear to me that the truths of the faith are incarnated in union with Christ in the Eucharist. Jesus came to us poor. His birth was announced first to the lowly outcast shepherds, who were regarded at the time without an ounce of romance. And yet God called these men, thought of as dirty, perhaps sub-human and mostly unseen folks, first.

Jesus is known in the breaking of the bread. Jesus is known when we are broken and shared not as people giving service, but as friends. ‘I no longer call you servants, but friends’ (cf. Jn 15:15). The Eucharist is the source and the summit of our faith. How can we be friends with Jesus if we are not friends with the poor, with whom we are also poor?

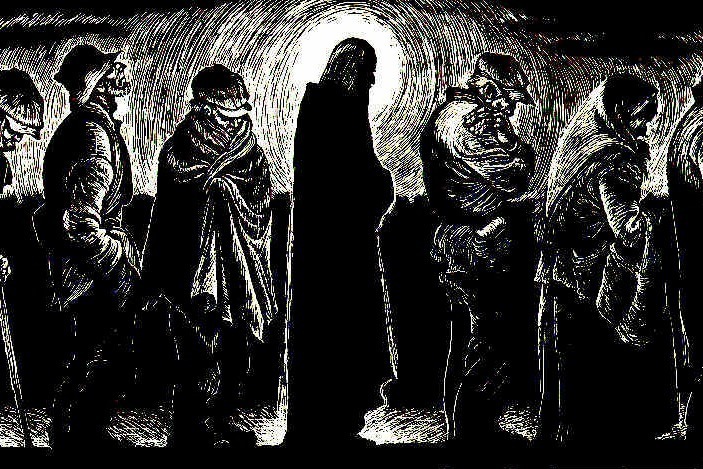

Featured Image: Fritz Eichenberg, Christ of the Breadlines, detail; courtesy Jim Forest via flickr, CC-BY-NC-ND-2.0.