Worldly Obedience and Faith

Whoever considers his existence must admit that he cannot control countless things that are laid upon him in a compulsory manner. He is aware of many of these from experience; he has thought about them or run into them. There are many, too, of which he is unaware, but whose reality he acknowledges without giving an account of them and often in complete disinterest. At work he is fixed in his occupation like a link in a chain, and he cannot break this chain—not even bend it. Working hours are determined. Superiors are appointed. A host of appointments must be kept. The pace of work and required performance can be set, or one can only adjust these very slightly. He is also dependent upon his co-workers. If this or that is not provided, he cannot do his own job. If another does not help him, he will not finish. He depends upon materials, upon a thousand circumstances.

If his work interests him, he will want to study the process in which he is involved in order to review the achievement of his predecessors to try to learn what will become of the work he will hand on. Whether one is a handyman or a chemist or an attorney, one seldom starts at a true beginning. Rather, one accepts what others have worked on, which, for him, is only relatively “raw material” that he will further process in order to deliver it reconfigured somewhere else. Often, he will be able to observe the success of his work, but not always. Perhaps he has to spend hours only operating the handle of a machine without seeing what it produces. He must insert himself into an entire process; this can be a burden for him, but he has to live, and existence brought him to the choice either to force himself to do this work or to look elsewhere. So he chose this work—perhaps it was not much of a decision, more a fate laid upon him that hardly waited for personal consent—because it appeared to him reasonably suitable for the existence he has to lead. Still less does he expressly choose to remain there. The fact of his continuing existence simply imposes it upon him. Whether his work appears to him to be useful, whether it suits him—one soon stops asking such questions. He needs the pay, and, besides that, he retains a certain freedom: he can do this just as well as something else. Being tied to the machine, to the work shifts, to the personal relationships of the plant or, if he happens to have a more sophisticated job, to the cases that present themselves to him as a doctor, to the parties he must satisfy as a legal advisor—with all of this he contents himself and always looks forward to so-called free time.

If he thinks about this, however, he will also see a host of dependencies. His environment influences him. Here, too, much more than he thought, he is one who is inserted and who must comply. He can act as though he reigned; at home he can tyrannize his wife, scold the children, and play the part of a great lord. Nevertheless, he must learn to eat the bread that has been purchased, even if today it is too dark and not to his liking; he must bear with the noise of his neighbors, and the more he requests, the more deeply he falls into dependency. Were he a model citizen, he would be the man who does not rebel, but who much rather fits in everywhere, who somehow in his demands keeps pace with advancing technology, who possesses the power of mind to bear everything that weighs him down, bores him, and disturbs him. There he would attain to being a master—everywhere else he is a slave, or his freedom is at least hampered. In this respect, he does not essentially differ from everyone else.

He bears this fate together with all. If he buys something that delights him, at the same time he divests himself of certain freedoms—neither acquisition nor wise docility makes him freer. He could most likely still imagine himself to be free in intellectual matters. Probably, no one can keep him from spending an hour a day considering a certain issue, solving a math problem, acquiring some knowledge or even an education. Even here, however, he bumps up constantly against boundaries: unlimited spirit is not available to him. Boundaries are even imposed upon the play of his imagination. He constantly asks himself: “What now? What next?” He might imagine tackling some problem that no one else has faced. He might consider it until he arrives at a unique and definitive solution. He might persevere until he actually reaches this goal, but afterward the emptiness would be there once more, with a thousand further questions that arose along the way to the solution and that now cry out for solutions of their own. It might happen that he then becomes conscious of his own finitude, futility, and transience as never before. Profound discontent and hopelessness can beset him. Perhaps then he remembers the Christian faith.

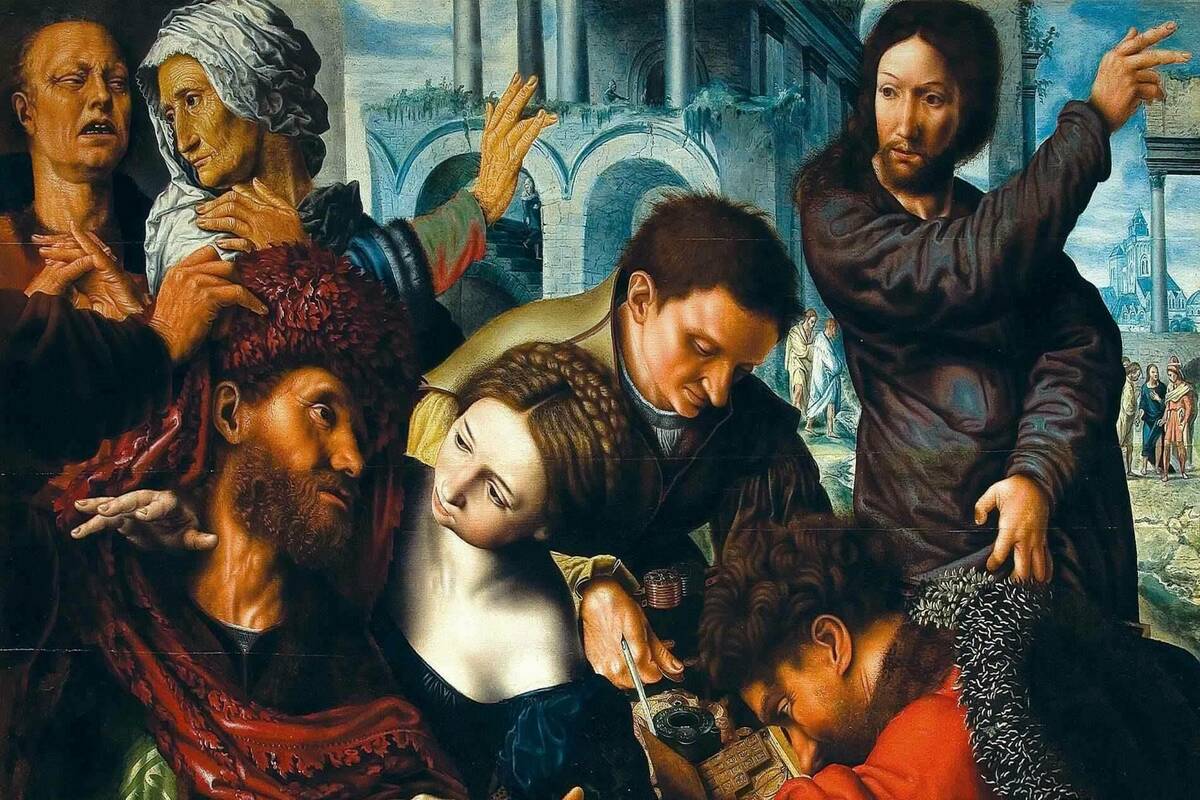

The solution that faith offers him is not a consolation for those who have resigned themselves. It is, rather, a solution unto hope. The obedience that man is compelled to render things does not become less severe for the believer, but the entire drudgery recedes to something secondary. Certainly, one of man’s tasks lies in doing his worldly work as it must be done. Faith, however, gives to things and to the work done on them another appearance. My fellowman is no longer first of all one who performs the same drudgery in front of me, next to me, or behind me; he is someone to be loved, someone to whom I must mediate something of what radiates from faith. Wherever my fellowman appears, whether at home, in the workplace, or wherever else, he is not to be missed; love points to him, he poses a question, and this question always finds its reply in the space of faith. He thus appears within a different kind of obedience, one that is already fully penetrated by hope, faith, and the question of love. Christian obedience becomes perpetually relevant through the Lord’s commandment to love: one’s fellowman is to be loved because he is “neighbor.” He must be regarded and considered. As one’s fellowman, he is first of all simply present. He does not especially intrude (drängt sich)—at least, not usually—or form any urgent (vordringliche) matter. The Christian, too, who is supposed to consider him in the commandment to love, does not intrude (drängt sich). That which is urgent (das Drängende) lies in the commandment itself.

At first, the commandment stands there as something neutral. It is one of Christ’s remarks, a word that he spoke to his companions along the way. It is a demand of the most general kind. Whenever Christ speaks, however, he issues a living, effective word that wants to be received and will only then show itself to be what it is: a request for the same obedience as that which the Son renders the Father. Christian obedience would thus be, in a first, most general description, the reception of the Lord’s commandment to love, agreement with the one who lives it himself before God, and the adjustment of one’s own life to the meaning of love. At first, everything is almost formless. Above all, more love is demanded, and you and I and he, we must love in order to meet this demand.

This demand of the Lord is the first thing we encounter that knows no boundaries, that is not determined by this or that limit, this or that measure of time, by the laws of workflow and free time, by the choice of some hobby. Rather, it is universally valid, enlists the whole life of man, and indeed, not from the perspective of man’s need, but from that of the word of the Lord, which claims one’s entire lifetime for this end.

Each human assent to love is like a tiny drop in the sea. Before long, it ceases to be recognized because all of the drops belong to the whole, to a unity that flows forth over the whole world. This unity, however, has its recognizable source in the word of the Lord that he himself speaks in obedience to the Father. Our obedience is the will to be this single drop in the sea—better yet, to be any drop without distinction, without a mark of identification, without recognition. Countless drops are needed in order for this sea to exist. That I am precisely this one drop and have only an indefinite, implicit notion of the others corresponds to the meaning of Christian existence: anonymous obedience that enters into the whole ultimately means, because of the love that the Lord has for each one, distinguished obedience, an obedience that is consistent and momentous, expected and demanded to be so by providence.

Love: The Other Word

As soon as the commandment to love one’s neighbor gains for a man a resonance that he understands and that concerns him, obedience and responsibility also acquire a new appearance. Whoever is addressed must respond and, indeed, not anonymously, but personally and uniquely. This uniqueness of the response becomes pregnant ever anew with responsibilities as well as integrations, opportunities for a further response, and urgency. It also generates something new, insofar as until now some things were known but not heeded. All the new features ultimately derive from the word and the face of the Lord. The features are different, each according to the one who gives the response, and yet they all belong together, and their unity lies in the word and the face of the Lord.

Now the man abandons the neutrality he has maintained until now. He must show his true colors. He is also exposed: dangers arise, for now he is observed and excites offense. Before he was finally willing to obey Jesus’ commandment, if he wanted to parse it in advance, to delimit the obligations, to outline obedience, he would thereby design something that has little in common with reality. Reality is always different from the plans to deal with it. Whoever only considers the decision and its possible consequences is still far from being the one who actually bears these consequences. Such a one is in a state of suspension; he does not yet know what will happen. If, in the moment that we recognized Jesus’ commandment, we were to envision how to obey it, certain faces from our surroundings would probably emerge. We would undertake to fulfill the commandment toward these people. We would plan the necessary steps and make the arrangements.

But readiness for obedience to the Divine Word requires first of all a complete interior cleaning, an emptiness, an availability, a complete readiness for everything that the Word might work or command. In the moment of decision, what matters is letting everything go, even at the risk of seeing one’s entire self disappear, because another world claims us. Everything that until now counted as one’s own: the time of work and of rest, for example, the natural rhythm of day and night—all of it is offered up so that the Word can work as it wills and not be limited and compromised by our deficient readiness. If we want to be the measure for the Word ourselves, then there can be no talk of Christian obedience. And we alone would be the truly deficient ones, were we to protect ourselves against the Word of God by setting limits and conditions.

Relationships hold sway between man and things and time, and in a certain measure, man has things and time at his command. He must, however, hearing the Word of love, let go even of this last control. There is a listening to the Word into nothingness—into something that, at first glance, has little to do with eternity, but still less to do with the present, because the Word lasts and abides and its perpetuity grounds something that cannot be overlooked. The more man considers this, the more he gets a sense of the way that everything he has until now called his existence consisted purely of things that only had very fleeting worth and then withdrew from his disposal. These included delightful as well as repugnant things and many to which he was indifferent but that were nevertheless there. Everything woven together yielded his existence, that in which he had grown up, that had shaped his life until today. Inside this patchwork there suddenly sounds the command of obedience to love. He who is a thousand times conditioned hears the Word, which is unconditioned, which comes from another world, and he is himself supposed to become that other whom the Word claims. At first, perhaps, he thinks that it will be done with a single listening and obeying and that all the details that surrounded him and constituted his very self are thereby more or less overcome. Perhaps it is precisely this idea that helps him to a first confident Yes. If he then begins to consider his fellowmen from a new perspective, he can make the discovery that those who are reputedly obedient to the Word do not particularly stand out, do not attract attention with any brilliance, so that he has little desire to make their fate his own. He learns some things about their way of life that appear to him hardly worthwhile; he sees, perturbed, that behind their obedience a mystery conceals itself that is no longer traceable. He cannot apply any human measure to it; the measure that is contained in the Word is apparently a measure of God that man can apply neither to himself nor to another.

He also does not quite know how to carry it out in order to follow the one Word. Until now he has obeyed a thousand words, at times orienting himself toward one word, and then toward the other; now that he prepares himself to obey the one Word, he does not see how one does it. Once he gathers his courage together and attempts it anyway, he discovers, amazed: this Word is so alive that it has the power in itself to make the agent capable. It is the Word that asserts itself and unfolds itself within him. When he has grasped this, it also becomes clear to him that human “self-realization” is an empty word. By the inner power, speed, and steadfastness with which the Word of love unfolds itself, he recognizes that alone this Word has the power to assert itself in man. It is not as though it would spread through a kind of contagion, but rather the fullness of the Word fulfills itself in man.

The Church

“It is no longer I who live; Christ lives in me”: Paul’s word expresses a truth that applies to each Christian. It is not, however, as though everyone individually must offer himself to the Lord as a dwelling and would thereby have done enough. Nor is it that everyone stands under the same law of the love of neighbor as his fellow Christian, whose openness to the Lord nevertheless does not concern him because he must himself be thankful to some extent if he is to become a dwelling for God. It is much rather that if the Lord dwells in Paul, this man represents the Church instituted by Christ. The Church is not only a frame for the individual parts of the enframed picture, which only remain together as long as the frame contains them; as an institution founded by the Lord, she is also herself an image that accepts the believers, integrating them into herself, and she takes into account their particular colors, lights, and shades. She administers the Word of God and the sacraments, from which the individual lives in his innermost depth. She poses many questions to him that he has to answer, but one can just as well say that the individual poses the Church many questions that only she can validly answer for him. She lets the Spirit blow through her and continuously receives him in order to give him away and be formed and unfolded by him. And because she receives the Spirit immediately, and the truth is given to her for administration, she demands obedience and discipleship, allocates to each one his place according to his ecclesial gifts of the Spirit, which she administers and whose measure lies with her.

And this place that is assigned is no resting place but, rather, a place within an order of obedience, within a hierarchy, on a plain far above the individual. Because the Spirit blows through the Church, vivifying her, this plain is never fixed and dead but, rather, is a source that bubbles over with life. The Church as an institution is herself configured to the Trinitarian God in a relationship of obedience; even the highest office-bearer cannot suddenly will to believe things or will to let things be believed that do not stand within God’s living plan for the Church. The “little man,” who believes but possesses little understanding, will perhaps never feel the moment of obedience to the Church very strongly. He will fulfill the duties demanded of him naturally and without questions; he will keep his Easter and receive the various sacraments at the appointed time without asking much because he simply adheres to the Church’s answer to his question about what he should do. His fellow Christian’s example will help him insert himself into the current of the tradition before and after him. He would be astounded perhaps if one were to describe his attitude as obedience. Nevertheless, he obeys, as do the others. Here and there he does so grumpily, but without serious rebellion. He demands for himself no special law; he does what the others do, too.

One who is spiritually more alert, one who has been formed, will likely consider some of this ecclesial conduct to be genuine obedience, since it awakens unresolved questions within him. He will not always be able to understand fully why something that he wishes to be different is not possible and he has to yield. But the Church also possesses answers for him, more differentiated answers in which the inquirer, if he is attentive, will sense the blowing of the Spirit more clearly and will feel the Spirit blown upon himself. He renders a more conscious obedience, absorbs more consciously first what the Church says, and he holds it to be true, and only then will he raise his objections and, in the response he receives, experience the ever deeper insight of the Church. Thus will he also appreciate better the legitimacy of the demand of obedience and the extent of its claim. He will further understand that an order must govern the community; he will also see the priest as one of those obeying within a hierarchical order, which can never exist otherwise than through the fulfillment of obedience.

The order of the Church now appears as an organism of obedience, wherein one has to fulfill this and another that in the space that has been outlined, but this whole obedience is a spiritual one, whose meaning reaches much deeper than one initially thought. It therefore also imposes a greater responsibility, all the more so, the more awake is the faith that senses how subtly the effects of Christian actions branch out in every direction. The whole activity reaches out toward the Head of the Church, who performs the whole obedience to the Father and recapitulates it in himself, without the believer being able to picture very much to himself by this truth. Obedience fastens into obedience; something set fits into something else that has been set. Thus it runs to the exterior of rites, which structure the liturgies and the sacraments, to the formulation of the dogmas that establish the faith and make it into a clearly felt act of obedience. Obedience of the individual mind to the Church, of the mind within the Church, of the Church to the Lord, of the Lord to the Father. From the outermost leaf to the deepest root, the tree forms a whole that lets itself be understood as a unity most clearly in terms of obedience, of the Son’s will to obey, which he granted to his Church. Extra Ecclesiam nulla salus: salvation embodies itself in the Church because only in the Church is there real obedience.

As the unbeliever, in his freedom, which he wishes to manage by himself, sees himself unexpectedly placed before new boundaries and forms of obedience, so the Christian finds himself in the Church with thoughts that have nothing directly to do with the Church, and yet always unexpectedly again in the field of an outlined ecclesial obedience. There is no evasion—such a thing is never intended. Since God the Father created all things unto the Son, they all already contain preliminary traces of obedience, which the Son, at the Incarnation, elucidated in the Church. Through the Church, he has imparted clearer and more easily graspable outlines to the whole obedience.

The Christian has in the Church enough of a motive to insert himself into obedience. Sometimes this obedience, viewed from the outside, can be difficult for him. But prayer, the gaze toward Christ, the will to follow him—these help to overcome the obstacles. If he believes it to be true that he no longer lives but Christ lives in him, he only needs to let this word become true in himself in order for obedience also to live in him. This holds even for the times when he discovers all kinds of failures in the Church and feels impaired as a believer, for obedience is for him a power that cleanses and strengthens him, drives him to loftier actions, empowers him to hope anew. Some things in the Church he cannot change, but there are also areas where new things may be discovered and built. Until now, many things were hidden, and they come forward at the appointed time efficaciously. New guidelines and the proclamation of a new dogma are always a witness that the vitality of the Church has not died away; and if she includes in her demand for obedience a new aspect of the truth, then this is likewise a sign of her constant liveliness (and not of her ossification), the co-execution of which she entrusts to the believer—all the more so as the new lies asleep in the old and in that respect was already implicitly affirmed. There is the silence of the Church; there is also her speaking. At certain times, her speaking breaks through her fruitful silence, in order to show what in her silence has ripened: this fruit ought to be accepted with joy by the believer’s new and, indeed, old obedience.

EDITORIAL NOTE: This piece is an excerpt from On Obedience, courtesy of Ignatius Press, All Rights Reserved.