Expectation

The acclaimed Norwegian author Jon Fosse is in the process of publishing a novel, Septology, in a style that he calls “mystical realism” and “slow prose.”[1] It is a masterpiece of renunciant, Eckhartian negative theology—or, if I may coin the adjective, “Adventine.” So to begin, we need to think about what Advent connotes from the point of view of a writer or any creative artist.

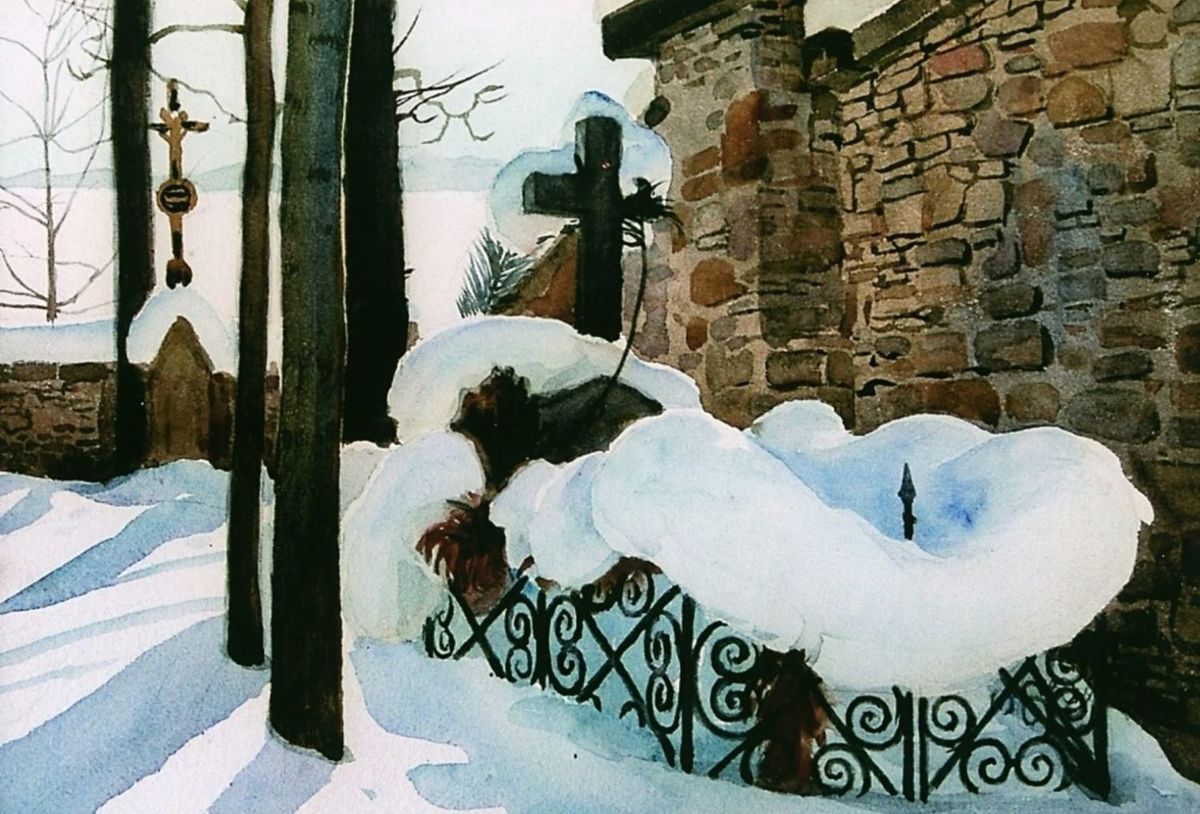

This is where writers and artists start: What is going on in the sky? What do the soil and the woods and fields and streets smell like? Does the wind blow and the sea flow, and is the air cold or warm? What is there to eat and to drink? And who is here by my side? If you cannot get the weather down in a novel it is scarcely worth writing, you might as well write drama. (Fosse has written plenty of drama.) Because in northern countries like the west of Norway where Septology is set, Advent means encroaching dark and cold, everything about the earth around us and the shifting weather, though we remain sensitive to it—precisely if we are sensitive to it—serves more readily to turn one inward or dispose one to contemplation and recollection.

We gather ourselves together to kindle the light of inward attention, and we gather with others in the world to make warmth and mark that part of life lived in relation by the ceremony of reunion. The repetition of seasonality is so strong a catalyst to memory, and so precarious is our purchase on seemingly linear time, that the answer to the question “Who is here by my side?” may include those who no longer are here with us, but with whom we once shared this time of ingathering.

And Advent is the time of expectation. To really grasp what expectation is, think that we say of a woman who will deliver a child that she is expecting. That is the kind of attention that Advent connotes, the attention of fullness, of pregnancy—and of intense coming labor and change of life. It does this directly in the sense that it is the season leading up to the celebration of the birth of Jesus.

Before getting to anything abstract it is important to recognize the holiday as the celebration of a very real woman giving birth to a very real human being. Everything seems to begin for us down here on earth, in the phenomenal world, the world of actuality, and so all fiction must work coherently at that level of being. But the question, especially for the writer of fiction, is what it all points toward or intends, what relation holds between this world and the world of potentiality.

So we do come to a more ideal or inward way of thinking about Advent and its endpoint. In the mystical theology of Meister Eckhart, which informs Septology (Eckhart is quoted in German and referenced in the text on several occasions), the essential narrative or quest of the spiritual life is that of the birth of the Son in the soul. This is a birth predicated on death—death to the creaturely world of finitude, at least as taken in itself rather than in God.

The fullness of Advent, its growing pregnancy, concludes in the emptying out of birth, and is predicated on the prior emptiness of the womb that is the soul: for if the soul—and every soul in the Christian tradition is thought of as feminine in terms of its potentiality or receptivity in relation to God—if the soul were full of the world then it could not conceive and carry and finally bring to birth the Son. For Eckhart, it is nothing or emptiness that gives birth to God. In Sermon 19, for instance, he reports what may have been his own vision:

It appeared to a man as in a dream—it was a waking dream—that he became pregnant with Nothing like a woman with child, and in that Nothing God was born; He was the fruit of nothing. God was born in the Nothing.[2]

The question posed in Septology is how to evacuate the ego and arrive in the emptiness where God may be received.

So we return to the first connotation of Advent as season of darkness, void, purgation, detachment. This last Eckhart elevates above all virtues, even love, for “if the heart is to be ready to receive the highest,” he says in his short treatise on detachment, “it must rest on absolutely nothing, and in that lies the greatest potentiality which can exist. For when the detached heart rests on the highest, that can only be on nothing, since that has the greatest receptivity.”[3] In Advent, imagined as preparation, we see emptiness figured as the dark illumination or fertile void in which all things may be renounced so that all things may be regained transfigured, no longer standing (or seeming to stand) in themselves but in God, in their true ground.

That is how Eckhart thinks, a theology equally negative and natal, or maternal (from the deep etymological root that means womb), or Adventine. And this is the guiding thought of Septology. But how in the world—and of it—do you actually make a novel from such thought? That the earthly season of Advent should serve as objective correlative is obvious enough, but in what sense can fiction or story be a suitable means of representing detachment? What narrative interest can there be in this spiritual event? Partly, I think, the answer lies in the way fiction transcends itself, and partly in the way fiction—especially the so-called novel of consciousness, which is what we have at hand here—is founded in recollection and repetition.

Fiction Beyond Story

SPOILER WARNING: major Septology spoilers ahead!

The novel as a whole is called Septology, but that is just a description alerting the reading to a work in seven parts, of which five have so far been published (in the UK edition). The novel is being published in three volumes (I-II; III-V; VI-VII), and each of those volumes has a proper title. The first volume is The Other Name, the second is I Is Another, and the third will be called The New Name (These are literal translations of the Norwegian titles.) The epigraphs to the first volume come from Revelation 2:17: “And I will give him a white stone, and on the stone a new name written, which no one knows except him who receives it”; and from the Agnus Dei: “dona nobis pacem” (give us peace). In these we discern the title of the final volume (implying perhaps that the “other” name of the first volume is the one we bear in this life), and the detachment or peace that passes understanding, a prominent theme in the mystical theology that shapes the fiction.

The epigraph to the second volume is the same as the title and comes from a letter that the French poet Arthur Rimbaud wrote in his visionary youth, before he renounced poetry. I glean from these an idea of the self we are here below and the self we might be on the other side of death, and from the peace of God quoted from the liturgy perhaps we have also the inkling that the earthly self may have of its heavenly counterpart or destiny. I will add that the phrase “I is another” might be applied to the Christian idea of the spousal relationship (including the espousal of the Church and Christ or the soul and Christ), and even to that of the neighbors we are to love as ourselves and only in whom, it may be, we can love ourselves.

The basic grammar of Septology is first-person present tense from the point of view of a painter named Asle, an older man but still able-bodied. I will refer to this point-of-view character as Sober Asle. He lives alone in an old house on the remote coast north of Bergen. Once he was married to a woman named Ales. She died many years before (we do not know exactly when) and they were not able to have children (we do not know why). Ales was partly of Austrian heritage and for this reason she was a Catholic. She too was a painter: toward the end of her life, we are told, she painted only holy icons, and she read medieval mystics, especially Eckhart, whom she was apt to quote. It is because of his wife that Sober Asle became sober—drink had completely taken over his life—and became a Catholic at the same time. This is the solid core, the couple, in which the book is grounded and the source of our point of view.

The only neighbor of consequence in the present timeframe of the story is an old bachelor named Asleik. He lives alone, but frequently visits Sober Asle, whom he gives firewood and mutton and fish from his own labor as farmer and fisherman. Rustic Asleik also provides Sober Asle with unsolicited but eerily astute comments on Sober Asle’s paintings. In return, Sober Asle often gives Asleik groceries and other supplies that he picks up in faraway Bergen, which Asleik cannot easily reach because he owns no car. He also gives Asleik one painting every year, to give to Asleik’s sister Guro as a Christmas gift. Sober Asle is acclaimed as a painter so these works are worth something (Asleik always picks out the painting, and Sober Asle thinks he always picks the best paintings).

Sober Asle has never met Guro, who lives a ways up the fjord, despite the fact that Asleik spends every year at his sister’s for Christmas and always invites Sober Asle to accompany him there for the holiday. Asleik refers to Guro simply as Sister. This kind of elemental nomenclature pervades the novel, e.g. The Alehouse, The Clinic, The Hospital. Guro, or Sister, once lived with a man referred to as The Fiddler, an alcoholic she eventually drove out. Sober Asle cannot stand Asleik sometimes, they are always saying the same things to each other, repeating the same observations and ideas, but at other times he is surprised and impressed by the sort of wisdom Asleik possesses despite his parochial nature. All told their neighborliness is enjoyable and slightly humorous for the reader. They are like monks (Asleik actually says at one point that Sober Asle looks like a Russian monk), these two old men who live alone, and yet they are not alone thanks to their neighborliness, which one senses is vital as a theme—one instance of the paired or doubled life—and not merely as a structural device.

And then there is the other Asle. Septology can be classified as a doppelganger novel. I will call this other Asle, Drunk Asle. He looks and dresses the same as Sober Asle. Like Sober Asle, Drunk Asle is a painter, even a supremely talented painter. Or he was. Now he lives just outside Bergen in an apartment with a dog named Bragi, and can do little but drink and dream of paddling out to sea in the night never to return. Drunk Asle has been friends with Sober Asle since they were young art students together. Drunk Asle has been married twice and has three children, but he is estranged from both the mothers of his children (their names were Siv and Liv), and from those children. And, of course, Drunk Asle has never stopped drinking (or become religious). Now the alcohol is killing Drunk Asle, he can hardly eat anymore and suffers delirium tremens.

Septology I begins on a Monday in Advent, close to Christmas. These are the first lines:

And I see myself standing and looking at the picture with two lines that cross in the middle, one purple line, one brown line, it’s a painting wider than it is high and I see that I’ve painted the lines slowly, the paint is thick, two long wide lines, and they’ve dripped, where the brown line and purple line cross the colors blend beautifully and I’m thinking this isn’t a picture but suddenly the picture is the way it’s supposed to be, it’s done, there’s nothing more to do on it I think, it’s time to put it away, I don’t want to stand here at the easel any more, I don’t want to look at it any more, I think[4]

There are no end stops in Septology, and the prose is only broken when dialogue is reported, but the syntax is correct (commas effectively function as end stops) and easy to follow, the diction always simple and clear. Each of the five parts of the novel published so far begins with these lines or something very similar, Sober Asle looking at himself looking at the Saint Andrew’s cross (Asleik is the first to identify it this way). It is important to note two things here. The sentence begins with “and,” which is to say that it does not begin at all, rather it signifies the point at which we immerse in the consciousness of Sober Asle. And the other thing to note is that Sober Asle sees himself—he is not necessarily actually standing before the painting looking at it, but he is thinking of himself looking at it.

“I think” is probably the only phrase that appears more often in the books than “I see,” always serving to remind us of what we are reading, namely a representation of consciousness. In other words, Sober Asle is not actually narrating. He is not, in fact, a narrator at all. Before I pick up on that point, though, let’s note how each part ends (so far, but I expect the remaining parts will continue these trends): in prayer. The first part ends with the Ave Maria (in Latin) and the other four parts so far published end with the hesychast or Jesus prayer, which follows the Ave and the Pater Noster (Sober Asle likes to pray in Latin) that he says while thumbing his rosary. Here is the end of the fifth part:

and I hold the brown wooden cross between my thumb and finger, and then I say, over and over again inside myself while I breathe in deeply Lord and while I breathe out slowly Jesus and while I breathe in deeply Christ and while I breathe out slowly Have mercy and while I breathe in deeply On me[5]

I think it worth noting that consciousness includes the body: he prays with his whole body.

Most fiction is story, which means that it is told, for there is no such thing as story except in the telling of it. Thus most fiction is mediated by a narrator, which term literally means one who tells. Had the development of Western languages gone a different way, we might have used the word historian instead of narrator. The root of the word story is the Greek historia, which means an inquiry. A story is a kind of report of things learned or witnessed. Because of this fact, so basic as to be seldom acknowledged, the default tense of storytelling fiction is the simple past.

Stream-of-consciousness is a unique form of fiction that makes use of no narrator and so is not story, properly speaking. It is possible to think of stream-of-consciousness as fiction’s stylistic means transcending story to become something more like prayer or certain modes of poetry. Instead of a story, in this style of writing what we have is the representation of consciousness, and that representation is meant to be immersive. The words of Septology are not to be understood as Sober Asle’s articulation, even to himself, of what he is thinking—he is not a first-person narrator or delivering a dramatic soliloquy—they simply are what he is thinking. Stream-of-consciousness has to be rooted in the present tense, since a default past tense would indicate report, i.e. story. Stream-of-consciousness is a journey or glimpse into the origin of story.

So what happens in the present time of Septology? What origin are we watching take shape? Outwardly, there is little. The writing is solid: there are no fissures. We cannot suppose consciousness to cease except in sleep; and that is how Septology is written, we are inside Sober Asle’s mind all while he is awake. In the five parts so far published, we cover four days in what may prove to be the last week of Advent. When the book begins Sober Asle is not in fact standing in front of his painting, the Saint Andrew’s cross he is obsessing over throughout the novel, he is driving home from one of his shopping trips to Bergen—and so right away, or as soon as we realize this is what’s happening at the beginning of the novel (it is evident about eight pages in), we see what sort of mind we’re privy to in this book. What Sober Asle “sees” or what he is conscious of is very often not what is literally visible to him. And whether this mental seeing is distinct from physical seeing is not always clear to Sober Asle himself.

When he is seeing what is not visibly there, it is one of three things: he sees himself in the past, either what he has just been doing or thinking or in the more distant past; he sees or feels and converses with his dead wife Ales; he sees the other Asle. The phrase besides “I see myself” and “I think” that recurs many times is “I see Asle.” When this phrase occurs in the present, we can be sure it is Drunk Asle he sees. But Sober Asle sees the past a lot when he “sees Asle.” At first, because we are primed to think that when Sober Asle uses his own name he is thinking of the man who shares that name, we assume that the Asle of the past is Drunk Asle. But we see more and more of this man’s past, and at a surprising moment we finally realize that the Asle he sees and calls by that name in the past has been Sober Asle—i.e. himself—all along. He has become that detached from his own life. Only when in the present Sober Asle sees Drunk Asle are they distinctly two men.

It is one of the chief burdens of the book to simultaneously establish and break down the distinction between the two Asles. In a similar way we are unsure whether, for example, Sober Asle really sees two young lovers in a park on his drive home from Bergen as the sky grows dark and it is beginning to snow, and watches them swinging like children and then talking and then making love—or whether he has just hallucinated this scene from (as we will come to suspect) his own past. And we are unsure whether deceased Ales “really” is there holding Asle’s hand and speaking with him or lying in bed beside him.

For this is the perhaps new proposition of Septology. It is not merely the representation of the consciousness of one man: it is the representation of everything as consciousness, or what it may finally be more accurate to call the spirit. We have in Septology a work of fiction that does not show us one atomized individual bouncing around the world reactively or rapaciously, his consciousness or mind or inward life one more thing on the same level with all other things and events and thus eligible to be a subject of inquiry along with them. We have instead a picture of mind as encompassing: mystical realism indeed. Sober Asle can embody this realism for us because he has been emptied out, his consciousness become a womb. But how did he get that way, and what does it really mean?

What Happens to the Heart

In a sermon Meister Eckhart articulates an idea of “works” which Sober Asle on numerous occasions appropriates for himself with regard to his painting:

A work as a work is not of itself, it is not there for its own sake, it does not occur of its own accord, or for its own sake, and it knows nothing of itself. And therefore it is neither blessed nor unblessed: rather, the spirit out of which the work proceeds rids itself of the “image,” and that never comes in again . . . If a good work is done by a man, he rids himself with this work, and by this ridding he is more like and closer to his origin than he was previously, before the ridding occurred, and by that much he is the more blessed . . . the spirit frees its being by working out these images . . . in this way it creates . . . readiness for union and likeness [with God], work and time being of use only to enable man to work himself out[6]

Sober Asle spends a significant amount of time thinking about and looking at his painting, and he has various thoughts about the art: that he knows a painting is good and complete if he can look at it in the dark or twilight and perceive a shining darkness or dark illumination in it; and he thinks that he is tired of painting, that for the first time in his life he has no more desire to paint; and he thinks of the paintings that he keeps and never puts up for sale at his annual Christmas show in a gallery in Bergen—including a portrait of his dead wife Ales; and he thinks that he needs to drive the latest batch of paintings to Bergen for that show, which is coming up soon.

And perhaps most telling, he thinks about how the paintings are images that become lodged in his mind and sort of torture him, and he has to paint them to get them out of his mind. Once he paints them, they are gone, he has renounced and freed himself of the images. Combine this idea with his growing recognition that he no longer wishes to paint, meaning there must be no more images crying out in his mind to be painted (he also thinks of paintings as speaking a wordless language), then we see an important way Sober Asle’s consciousness has been almost emptied.

As already noted, Sober Asle “sees” all sorts of people and events that are not actually happening before him. This ability precipitates the plot, such as it is, sending him back to Drunk Asle’s apartment to check on him as he suffers delirium tremens, but not finding him there and proceeding back into Bergen, where he finds Drunk Asle collapsed on the pavement in the snow. Eventually, after a few other stops and encounters, Sober Asle gets Drunk Asle to the hospital and himself checked into a hotel in Bergen. So ends the first day. But what we come to realize is that most of Sober Asle’s visions—the ones that are not of the dying Drunk Asle—are in fact his memories.

His life is playing out before his eyes, sometimes in a distracting way, punctuating his days and taking over long stretches of them while he sits in his cold and dark house, unable to muster the will to light his stove for warmth, or drives between his home and Bergen, or talks with Asleik. I think of this involuntary and visionary memory, which makes up a major portion of the book, as another form of ridding oneself of images. Sober Asle is recollecting his life in order to renounce it. Drunk Asle is dying of alcoholism in a hospital, but Sober Asle is also preparing to die. Even his wife tells him this is likely the case, that he and she may be together again soon. Septology is a study in how to make a good death.

Only the one who has freed himself from worldly attachments can die a good death, the death that is birth into new life. Already Sober Asle has renounced so much of life. He does not drink, has little appetite for eating, is always tired yet finds it difficult to sleep and apparently does not need much sleep anymore. He spends very little money, always dresses in the same outfit, and is so lost in thought and memory that he gets lost in Bergen despite the fact that he is retracing a route he has followed many times before. This is “slow prose” because it represents the consciousness of a man who in every way has slowed down.

In his visionary memory, it transpires that Sober Asle had a cruel mother. He had a beloved younger sister named Alida (all the principal names in Septology sound similar) who died suddenly in her sleep when still a child. He was molested by a grown man, a neighbor, when he was a young boy. He had a friend who helped him find some independence when he first moved away from home, and this friend had problems with alcohol and he, too, died suddenly of natural causes one day while still a young man. We learn that Sober Asle was once as sick with alcohol as Drunk Asle has now become. Through certain encounters we learn that he may, in his drinking days, have been unfaithful to his wife Ales, whom he loved greatly. And we learn many times that Ales died far too young, and without being able to first become a mother as she perhaps wished to be. Sober Asle uses prayer to calm his heart, empty his mind, and get to sleep at night.

But he remains troubled by these vision-memories, and volume V ends on a spiritual cliffhanger. Sober Asle is dining at Asleik’s. Every year sometime during Advent they have a dinner together. At the Advent dinner this year, at Asleik’s house, Sober Asle for the first time agrees to come to Asleik’s sister Guro’s house for Christmas. We have recently learned that the woman who may have been Sober Asle’s mistress is also named Guro. She does not appear to be the same Guro as Asleik’s sister, we can be fairly sure about that (or at least as sure, for now, as this novel allows us to be about individual identity), but all the same, no sooner does Sober Asle accept the invitation to Christmas dinner than he bolts for his car, where he begins the concatenation of prayer that ends every part of Septology.

He has already thought many times of how much he dislikes Christmas and prefers to be alone that day. Perhaps, we think, he panicked not from the thought of spending the holiday with a woman named Guro, but because Ales died on or near Christmas. We do not know that she did, but it is the kind of thing that Sober Asle would not think about, would bar from his consciousness, until he had no choice but to face it on that day that the book seems to be leading up to with dread. We may not find out why Sober Asle ends the fifth part the way he does, but it does not matter. What matters, as far as tracking the spirituality of this fiction, is what happens to the heart.

With that last clause I am quoting the title and refrain of a song by Leonard Cohen that appeared on his posthumous album Thanks for the Dance. In his final studio album, You Want It Darker and in the posthumous album, Cohen seems to have entered (at least as an artist) into the spiritual darkness that lies on the far side of the passions and travails of earthly life, when one is ready, even desperate, to renounce all things so that they may be known anew, recapitulated in God. It is intimately bound up with, maybe a version of, the dark night of the soul, and it is the dominant modality of consciousness in Septology. The essential line of the song in question is the version of the refrain that goes, “I care—but very little—what happens to the heart.”

This is the poise of paradox. It is an utterance of weariness, but even such an utterance can only be made if one retains a little heart, some last strand of attachment to this world. Up until the moment the “image” is totally gone from the mind, there is still some bond. Sober Asle has still, at the end of the fifth part of the novel, not yet got rid of the Saint Andrew’s cross that has fixated him. What happens to the heart for those who, like Sober Asle, have been broken down by life, what happens just before it ceases to be the heart, is this paradoxical simultaneity of self-transcendence while retaining that last desire, the desire to be free of the heart’s signal function, which is to desire. It is the moment—painful and protracted—of birth, when all that is left to desire is the highest that may be desired, the peace that is not the peace that the world gives.

Is all this darkly luminous mystical theology true? Asle, in all his empty, purified sobriety, does not know for sure. He has moments of terrible doubt. As he is in the car calming himself at the end of the fifth part, just before the concluding lines I quoted earlier, his inward disposition is shown in this way:

I start the car and I think that I need to say an Ave Maria to myself , that usually helps when the fear comes, which does happen, even if not too often and never without some specific reason, and then I say Ave Maria and that usually helps, I think and sitting there in my car I take my rosary out from under my pullover and I think now do I really believe in this, no, not really, I think and I hold the cross between my thumb and finger and I say inside myself Ave Maria[7]

Whatever he believes or fails to believe, Asle prays, and as I noted earlier, he prays until he gets to the Jesus prayer, the simple asking of mercy. I think all he knows for certain is that art is brief, life is long. As Eckhart says, works die away: after all, if they did not, then they could not rid us of the images that plague our days. But the days that furnish those images are long and hard and break us down. They break us down with the images, these moments that are seared into the soul, and everything breaks us down, the joy as well as the sorrow, each always begetting the other.

Even the natural and human beauty we behold somehow exhausts us. In the end, everything and everyone disappoints—oneself above all. Indeed you have no choice but to care very little what happens to the heart. The heart is weary. We feel, by the end of the fifth part, that there are only a few more vision-memories to be let go—no doubt the ones that have most devastated—before Asle will have brought to term that emptiness, that nothing, from which God is born.

[1] In conversation with Cecilie Seiness, Music and Literature, 10 October 2019.

[2] The Complete Mystical Works of Meister Eckhart (Spring Valley, NY: Crossroad , 2009), 140.

[3] Ibid., 572.

[4] Jon Fosse, The Other Name: Septology I-II (London: Fitzcarraldo, 2019), 12. NB: I am using the UK edition, because Septology I-V have so far been published by Fitzcarraldo. The American edition is being published by Transit Books, which just published I-II and will not bring out III-V until March of 2021.

[5] Jon Fosse, I Is Another: Septology III-V (London: Fitzcarraldo, 2020), 282.

[6] Ibid., 120. The italics and inverted commas are Walshe’s, and I am not sure why they are used.

[7] Ibid., 281.