And he dreamed that there was a ladder set up on the earth, and the top of it reached to heaven; and behold, the angels of God were ascending and descending on it! Then Jacob awoke from his sleep and said, “Surely the Lord is in this place; and I did not know it.” And he was afraid (Gen 28:12; 16-17).

The feast of the Guardian Angels, on 2 October, comes just after the feast of the Archangels, of Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael on 29 September. Who are these angels, and from whence do they come? What should we make of these ministering spirits (Heb 1:14), who present the prayers of the saints and enter into the presence of the glory of the Holy One (Tob 12:15)?

In the understanding of Christianity, as of Judaism and of Islam, there is an absolute distinction between God the creator, who alone is eternal and who does not so much have but rather is Being and Life and Truth and Beauty, and the created world, everything else that is not God and has existence only because of God.[1]

The first thing to say about angels is that they are creatures like us, brought into being and held in being by God. The Greek word ἄγγελος simply means messenger and angels are messengers sent by God to accomplish God’s purposes. Only monotheistic religions have the category of the angels, because only these traditions make clear that the beings who bring a message from the divine are not themselves divine. Angels are not small gods but are messengers of the one God. Angels are creatures and angels are concerned for human creatures because their fulfilment is to do God’s will and God is concerned for human creatures.

Belief in guardian angels predates the birth of Christ[2] but Christian belief in guardian angels is founded on the words of Jesus who said that each one of these little ones, that is, each human being, has an angel who beholds the face of their Father in Heaven (Matt 18:10). The revelation that each human creature is given into the care of his or her angel is a reminder that God is concerned for each person in the everyday matters of their lives, even the most mundane or prosaic.

God’s providence could be accomplished without the help of angels, for all things are dependent on God, but it is characteristic that God provides for creatures by means of the actions of other creatures who each play their part in God’s Providence. We might say that human creatures give their guardian angels something useful to think about and provide them with a particular way to offer service to God. At the same time, angels can help us understand the significance of earthly existence.

On Earth as It Is in Heaven (Matt 6:10)

In the film Wings of Desire, directed by Wim Wenders, Bruno Ganz plays an angel looking down on and wandering through the city of Berlin. The German title of the film is Der Himmel über Berlin, which could be translated as “the sky over Berlin” or as “heaven over Berlin.” As in many languages, the ordinary word for sky becomes the word for heaven, the place of the divine. Heaven is what is “above” and denotes spiritual realities that are above or beyond human understanding.

In one scene in the film, Ganz and other angels listen to the music of people’s thoughts in the public library. Some people are anxious about day to day concerns, others are reading, in different languages – one a science textbook, another poetry, another history, and one person is reading the first words of the Hebrew Bible: Bereshith bara Elohim eth hashamayim we'eth ha'arets “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth” (Gen 1:1). It is a line that already contains a glimpse of the angels.

That first line of the Book of Genesis is unpacked further in the rest of the first chapter, which describes God creating the whole world and all its inhabitants in six days, and is then explored in a different way in the story of the forming of the primeval human being from the dust of the earth into which God breathes the breath of life (Gen 2:7). The first chapter is about the whole world, the heavens and the earth. The next chapter is about the human being as a microcosm, a world in miniature, a being constituted of matter and spirit, of the earthly and the heavenly.

The first line of the Hebrew Scriptures expresses, in a fundamental way, what it is to believe in the one God, the Creator. When the early Christians came to formulate their beliefs, they started with this line: “I believe in God, the Father almighty, Creator of heaven and earth.”[3] The Apostles’ Creed, as it came to be known, was used as the basis for later creeds, most importantly the creed promulgated at the first general and ecumenical council of the Church at Nicea in 325 CE. The Nicene Creed moves from the metaphorical language of the earth and the sky to the philosophical language of visible and invisible realities: “I believe in one God, the Father almighty, maker of heaven and earth, of all things visible and invisible.”[4]

As an aside it may be noted that the new translation of the Roman Missal of 2010, better reflects the Latin version of the Nicene Creed visibilium omnium et invisibilium. The 1973 ICEL translation had rendered the phrase “of all that is, seen and unseen.” However, what is “unseen” may only be hidden until it comes to be revealed, as students may take an unseen exam.

In contrast, what is invisible is not only unseen but unseeable, at least directly. There are physical realities that are invisible, such as X-rays, but there are also spiritual realities that are invisible in themselves. A thought is not itself visible, though it may become visible indirectly, as when we write down our thoughts or when they are apparent in our actions.

The Nicene Creed was in turn expanded further, most notably in 1215 CE, at the Fourth Lateran Council, a gathering that was arguably the most influential of all the councils of the Middle Ages:

We firmly believe and openly confess that there is only one true God, eternal and immense, omnipotent, unchangeable, incomprehensible, and ineffable . . . the one principle of the universe, Creator of all things invisible and visible, spiritual and corporeal, who from the beginning of time and by His omnipotent power made from nothing creatures both spiritual and corporeal, angelic, namely, and mundane, and then human, as it were, common, composed of spirit and body.[5]

The Creed of Lateran IV is not well known and is not used in the liturgy (unlike the Apostles’ Creed and the Nicene Creed) but it is very rich theologically. It makes explicit that the creation of all things visible and invisible refers to the creation of mundane corporeal realities and the creation of the incorporeal angels. It then follows Genesis in moving from the creation of all things to the creation of the human creature who is composed of body and spirit and seemingly has something in common with brute materiality and something in common with angels.

However, this is only an apparent commonality (quasi commune) because human beings are different in kind from other animals: they are rational animals with a historical, political, cultural, and spiritual life. So also, human beings are distinct from angels because the rational soul of a human being is, by nature, the form of a human body.[6] Angels thus illuminate what it is to be human, both by what we have in common with angels and by how we differ from them.

A Spirit Has Not Flesh and Bones as You See That I Have (Luke 24:39)

To understand how human beings are both like and unlike angels there is no better guide than Thomas Aquinas, the theologian known as “the angelic doctor.” No Catholic theologian has excelled Thomas in his systematic account of the angels.[7] There are others who have written more extensively about angels, or more poetically, or who have expounded more of the stories and the purported names and subdivisions of angels, but none has gone further in seeking to grasp the nature of angelic existence.

Thomas was no materialist. He believed that some human activities transcend material causality. A thought, say the thought that the physical universe had a beginning, can be thought by different people. Even if it is a thought about the material world, the thought itself is not a material thing. To grasp a thought is not like grasping an apple. Only a limited number of people can hold the same apple at the same time but there is no inherent limit to the number of people who might have the same thought at the same time.

What is grasped is a thought and is the identical thought that might be grasped by someone else, which is why people can argue about whether the thought, for example the proposition “the physical universe had a beginning,” is true or not. The thought is not identical to any material expression of the thought (say a picture in my imagination), for that material expression is not identical in different thinkers. Thinking, then, as it involves the comprehension and the accepting or rejecting of thoughts, is not itself a material activity, even if, in human beings, it is accompanied by material activity within the human brain.

Persuaded by arguments developed broadly along these lines by the philosopher Aristotle, Thomas Aquinas held that thinking was essentially an immaterial activity.[8] Thus, it was conceivable, at least in principle, for there to be thinking without any relationship to matter, and thus for there to be pure intellects. Aristotle argued that there were such beings, and they play a role in his account of the movement of the spheres. Thomas, following the Jewish philosopher Moses Maimonides, identified the pure intellects of Aristotle’s philosophy with the angels of the Hebrew Scriptures.[9]

For Thomas, the nature of an angel is precisely the nature of a being that has knowledge and will but no inherent relation to matter. Such beings would have, in common with human beings, a capacity for wisdom and love and, again in common with human beings, would find ultimate fulfillment only through participation in a life that is beyond any created nature, the gift of God’s own presence. The angels behold the face of God not because they are immaterial creatures but because they have freely accepted the gift of God. This is shown most starkly by the fact that there are immaterial creatures who rejected that gift and do not see God: Satan and his angels.

Thomas was interested in how human beings are similar to angels, in having the ability to know and love other creatures and, through the gift of God that goes beyond this natural ability, in finding happiness through knowing and loving God. At the same time, he was probably the most consistent among Christian thinkers in his defense of the significance of human bodiliness.

He embraced the philosophy of Aristotle in large part because it helped him to articulate the essential unity of the human being as an ensouled body. This commitment to a corporeal spirituality was reflected also in Thomas’s personal religious devotion, exemplified in the writing of hymns for the feast of Corpus Christi, a celebration of the presence of the Body and Blood of Jesus Christ in the Sacrament of the Eucharist. In the Eucharist, the bread of angels is made into human bread (panis angelicus fit panis hominum).[10]

Human beings are by their nature material. We are animals of a specific kind and, unlike angelic thinking, our thinking is dependent on our senses and on our imagination. We cannot think about the world without experience of the world and abstract concepts like “the entire universe” are learned only through first understanding what we see and hear and feel. In contrast, angels think without sense perception in a way that we cannot imagine.

Thomas believed that angels could move material objects but that such action remained outside them.[11] In the Scriptures angels sometimes appear in human form (See: Gen 18.2; Josh 5:13; Tob 5:3-5; Mark 16.5), but Thomas argued that these bodies were not true living bodies.[12] Angels cannot truly eat or drink or feel the warmth of the sun or experience physical pain. Neither an angel nor a demon could conceive a child, despite what Rosemary’s Baby or The Omen tell you. In contrast, the living body of a human being is that human being and to touch that body is to touch somebody. This has implications for how human beings learn, how we come to be virtuous or vicious, how we come to the highest goods of friendship with one another and with God.

He Was With the Wild Beasts and the Angels Ministered to Him (Mark 1:13)

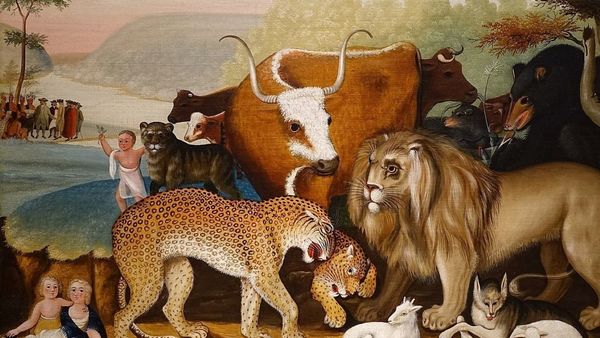

An unfortunate consequence of our forgetting about the angels is that human beings are seen as the pinnacle of creation. This is a trap that even theologians may fall into, misinterpreting the dominion that is given to human creatures (Gen 1:28) as though the world existed only for the benefit of human beings. In contrast, if God has created angels as well as human creatures, then it is more apparent that human beings are not so much on top of the world as in the middle, between angels and nonhuman animals, a creature among diverse creatures each of which is created by God. The image of Jesus in the desert with the wild beasts and the angels (Mark 1:13) is an image of the archetypal human being among creatures earthly and heavenly.

Seeing human beings only as top animal and always in contrast to other animals leads to an emphasis on what makes human beings distinct from other animals, an emphasis on rational free choice and autonomy, and, ironically, to the neglect of our animal nature. Even scientists sometimes fall into the trap of using the word “animal” to mean nonhuman animal. Whether or not someone believes in angels, seeing human beings in contrast with pure intellects is illuminating as it reminds us that the thought and action of a human being always occurs in some relation to the material world. Human beings are not separated intellects that stand apart from the bodily realities of birth and death, health and sickness, eating and drinking, sexual union and parenthood.

These brief considerations will, I hope, explain why someone who has spent 20 years writing and researching in Catholic bioethics might be interested in angels. Among the errors of contemporary secular bioethics, perhaps the most problematic is the construal of the body as something outside the person, a machine to be manipulated to suit our plans or desires. This leads to the belief that intentional sterilization, or causing a miscarriage, or causing someone’s death could be good or bad for a human being simply depending on what he or she desires or chooses.

It reflects a dissociation of the human being into an autonomous person and a passive body. A clearer understanding of the difference between embodied human beings and incorporeal angels would help us escape this dualism. Even in the world of bioethics the angels are sent to guard us and to keep us from stumbling (Psalm 91:11-12).

[1] See Thomas Aquinas Summa Theologiae Ia q.3, see Hebert McCabe “The Logic of Mysticism” in H. McCabe God Still Matters (London: Continuum, 2005)

[2] See David Albert Jones Angels: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2011), 11.

[3] The Apostles’ Creed from The Roman Missal, 2010, International Commission on English in the Liturgy (ICEL).

[4] The Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed from The Roman Missal, 2010, ICEL.

[5] Creed of Lateran IV also know (from its opening word) as Firmiter, this translation from H. J. Schroeder, Disciplinary Decrees of the General Councils: Text, Translation and Commentary, (St. Louis: B. Herder, 1937), reproduced by Paul Halsall (ed.) Internet Medieval Sourcebook.

[6] A truth that was defined as Catholic dogma at the Council of Vienne in 1311.

[7] Thomas Aquinas Summa Theologiae 1a qq. 50-64, qq. 106-114, see especially the 1968 parallel text edition with notes Aquinas, T. Summa theologiae, vol. 9: Angels (1a. 50–64), tr. Kenelm Foster. London: Blackfriars, also Jones, Angels, chapter 3.

[8] Summa Theologiae 1a q. 75 art. 2 see Aristotle On the Soul 3. 4, 429a. For a sustained presentation of an analogous argument see David Braine The Human Person: Animal and Spirit (Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press, 1992).

[9] Summa Theologiae 1a q. 50 art. 3 citing “Rabbi Moses the Jew” who wished “to bring both [Aristotle and Sacred Scripture] into harmony” see Jones, Angels, 40-41.

[10] The hymn Panis Angelicus comprises the last two verses of the hymn Sacris solemniis which is given for the Office of Readings on the Feast of Corpus Christi. For the Latin, two English translations and the music see “The Hymns of Corpus Christi—the texts of St Thomas Aquinas” prepared by the Liturgy Office for Adoremus National Eucharistic Congress and Pilgrimage © Catholic Bishops’ Conference of England and Wales https://www.liturgyoffice.org.uk/Resources/Adoremus/Corpus-Hymns.pdf Note that in the hymn the Blessed Sacrament is not itself the bread of angels. The “bread of angels” is a reference back to the Old Testament to the manna in the desert (Psalm 78:24-25) this was but an image (figura) of the much greater gift which is the man who came down from heaven, Jesus Christ (John 6:48-51).

[11] Summa Theologiae 1a q. 110 art. 3.

[12] Summa Theologiae 1a q. 51 art. 3.