To anticipate the formal expression of gratitude at the conclusion of this essay, I want to say at the outset that I have written this as a response to the invitation tendered by the Synthesis Report of the First Session of the XVI Ordinary Synod of Bishops to offer “theological deepening” of many of the ideas presented therein. This is, essentially, a brief essay in ecclesiology, hopefully relevant to several of the themes presented in the Synthesis Report. These themes are themselves echoes of many of the same themes that characterized much of the preparatory documentation, and I have responded to those in an earlier article.[1]

Twelve Points

· The first point is a contemplation of the beauty of the Church. The Church is resplendent with beauty. What is this beauty? The first point is what it’s not. We can think of the centuries of witness to the point of heroic virtue which has been exhibited in every century and in every culture in which the Church has laid down her roots. We can, in times of scandal, forget this, but it’s true, and astonishing and beautiful, that there is no culture in which the Church has laid down roots that has not produced martyrs, often in abundance, across all times and places. This is one of the traditional motives of credibility for the Christian faith.

But, beautiful as it is, the sum total of sanctity and of loving witness large and small throughout the last twenty-plus centuries is not the essence of the beauty of the Church. For that would make the Church’s beauty essentially flawed, since all of our virtue, even the most heroic and loving, is flawed. It would also make the Church’s beauty essentially no different, except perhaps in vastly higher degree, from the beauty of any other human organization or social grouping, such as, for example, Amtrack. If Amtrack has any beauty it would be the sum total of on-time trains that functioned perfectly with fantastic food and inexpensive fares, the sum total of its excellent human performance (itself perhaps only an eschatological propect). It’s a one-dimensional beauty.

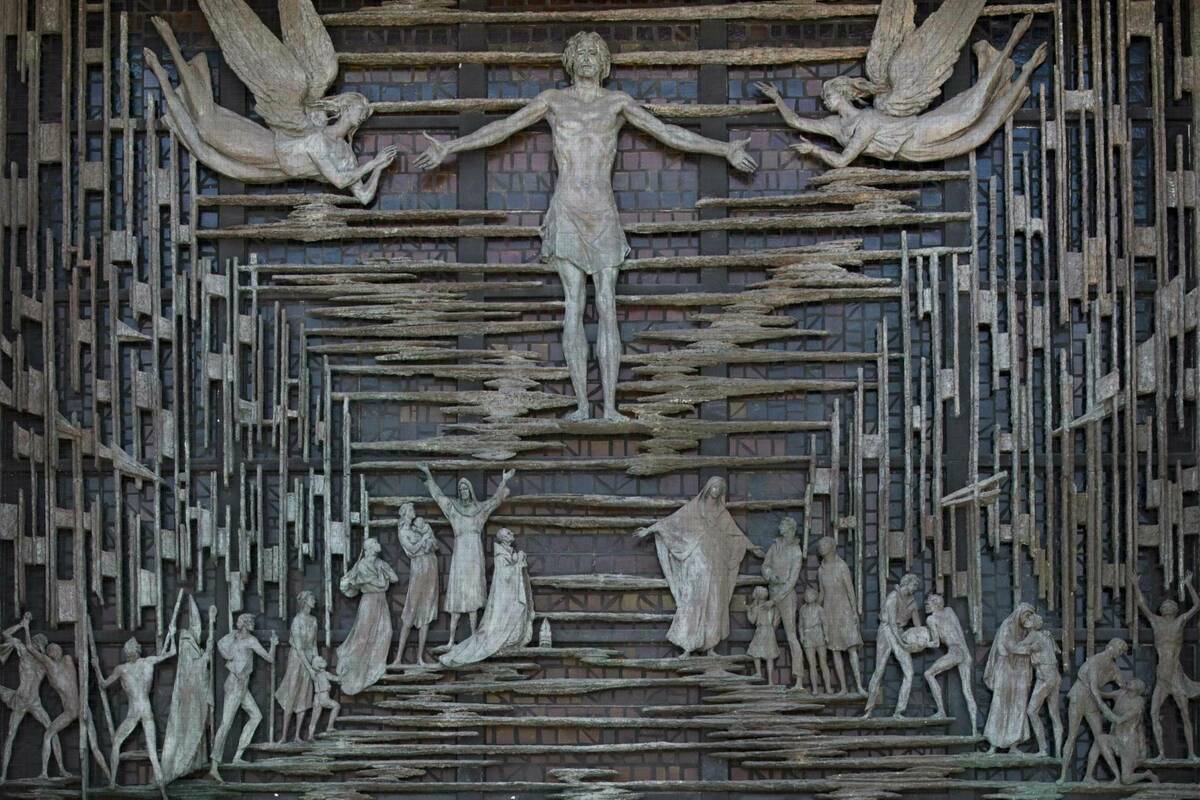

· So, second point, positively speaking, what is the beauty of the Church? It is quite simply the beauty of Christ, the Incarnate Word of God, who poured himself out in the most beautiful loving self-gift that there has ever been or could be. Lumen Gentium famously begins: “Christ is the Light of nations and consequently this Sacred Synod gathered together in the Holy Spirit, ardently desires to bring to all humanity that light of Christ which is resplendent on the face of Church” (LG §1).[2] The beauty of the Church is a wholly derivative beauty: it comes from Christ; it is he, the Light of Nations, that shines on the face of the Church. And yet the Church does herself really shine with this beautiful light, so that it becomes, in turn, her beauty. Christ the Word of God bent down not only to share our humanity, which he could have taken on in an unfallen state, but, as St. Augustine puts it, he also took on our mortality, becoming our “friend in the fellowship of death” (De trinitate 4.17, cf. 4.5) where we had looked for no friend, where we had not expected there could even be a friend!

The fellowship of death remains a fellowship of death, in a way, but it is, now that he has joined us as a free gift of mercy and love, a fellowship in his death and so in his love and so in his life. His love, the love that followed us even to death, is life, as the Resurrection reveals. This fellowship in Christ’s death, in his sacrifice, is the Church.[3] The Church shines with the light of Christ because she is a fellowship, a communion, that is constituted by his sacrifice. It is a communion in him, and through him, with each other.

· Therefore, third point, the Church is, unlike Amtrack, a Mystery. That is why the Church is an article of the Creed and Amtrak is not. With Amtrack, what you see is what you get. The Church is a mystery of the faith because, unlike all other purely human organizations, she did not and does not constitute herself simply by the will of the members to form an association. The People of God does not express the same reality as “We the People.” The Church is a communion in something we did not and could not possibly give ourselves, a communion not in some abstract love or thought of love or sentimental fellow-feeling, but in the Lord’s very concrete love, namely, his Blood. The People of God is a people purchased with the infinitely Precious Blood of Christ (see LG §9, alluding to Acts 20:28 and 1 Cor 11:25). The awesome beauty of the Church is that it is a communion in this very concrete love which we could not have given ourselves but which is the only love so utterly without ulterior or vested interests—unlike all of ours—that it can truly unite us to each other, and in a communion, the communion of saints, that endures unto eternity.

And yet, awesomely, it is a little like Amtrack after all, in that it is here and now, a visible human society in time and space, composed of sinners all. We don’t have to be perfect to be a member. Christ’s blood is poured out not by the thimbleful, for the 12 most perfect human beings that have existed or will exist, but freely, for all. He mixed himself with sinners, without contempt, out of love. But the communion in sin, in Adam, did not drag him into itself. Rather he, the Second Adam, transformed it by giving himself to us so that we sinners are now bound together in the love that defeats sin. This is what the Pauline language of justification by his blood means (see: Rom 5:9). We are his, and, on new terms we couldn’t have given ourselves, namely his terms, we are each other’s.

· Now the fourth point: the Church is therefore wholly a work of grace, it is not our work. It is first and foremost the work, the creation, the gift of Christ. This work was accomplished on the Cross once for all, but is made present in the sacraments, each in its own way. If the Church is a Mystery it is because she is born primarily of Christ’s sacrifice on the Cross, the sign of this is the blood and water, symbolizing Eucharist and Baptism, sacraments of the Church, that flowed from the side of the crucified Jesus (see LG §3). The Church is therefore a mystery of Christ’s sacrificial love. Since the Eucharist makes present that sacrificial love, the Eucharist “makes the Church” (see the Catechism of the Catholic Church §1396). It is true, of course, that it is Baptism that first incorporates us into the Paschal Mystery and thus into the Church, but Baptism, on its own and strictly speaking, at least in a Catholic ecclesiology, does not ultimately “make” the Church, for it is the first, not the last, of the three sacraments of initiation and as such is by its very nature ordered towards the Eucharist: “In Baptism we have been called to form but one body (Cf. 1 Cor. 12.13). The Eucharist fulfills this call” (CCC §1396). In fact, with Presbyterorum Ordinis §5, all “The other sacraments, and indeed all ecclesiastical ministries and works of the apostolate are bound up with the Eucharist and are directed towards it. For in the most blessed Eucharist is contained the entire spiritual wealth of the Church, namely Christ himself our Pasch and our living bread.” The Church’s countenance shines with the light of Christ because it is resplendent with the light of the Eucharist.

· Now we are (finally!) ready to talk about co-responsibility, starting with the fifth point: To say that the Eucharistic sacrifice makes the Church is to say that the Church is a work of Christ’s priesthood. The mystery of the Church is therefore a mystery derivative from Christ’s priesthood. His priesthood is mediated to the Church in two ways. One of the most outstanding contributions of Lumen Gentium was to recover front and center one of these two ways, the biblical and patristic idea of the priesthood of the baptized, which configures us to the priesthood of Christ and enables us to make spiritual sacrifices that build up the one Body, for example, in evangelization and in prophetic witness. These sacrifices are consummated in our participation in the Eucharist. The reason Baptism confers the dignity and mission it does is because it confers a share in Christ’s priesthood on all the baptized. This is one of the two mediations of Christ’s priesthood. The second mediation of Christ’s priesthood is another, different sharing in the one Priesthood of Christ. This is Holy Orders, and the difference between the priesthood of the baptized and the ordained priesthood is not simply a matter of degree.

That’s important, because if the difference between these two priesthoods were only a matter of degree, then the ordained priesthood would just have “more” of the baptismal priesthood, and that would mean that the ordained were super-Christians, the super-baptized. The ordained would have a Christian dignity above the baptized, but Baptism confers an equal dignity on all, and the idea that all members of the one Body are co-responsible for the being and mission of the Church comes first and foremost from the idea of this fundamental baptismal dignity (as the Synthesis Report rightly emphasizes). The two priesthoods differ therefore not merely in degree, but “in kind” or “in essence” (essentia): Holy Orders confers the ability to act “in the person of Christ the Head,” and thus to celebrate the Eucharist, making Christ present to his Body as our Head configuring the Church to his sacrifice and thus enabling the priesthood of the Baptized to fulfill its sacrificial role in offering the Eucharist. It also enables the priesthood of the baptized to fulfill its evangelizing role, because this terminates not just in biblical literacy or in mastery of apologetics but in Eucharistic communion. The two priesthoods are thus mutually ordered towards each other (ad invicem … ordinantur) in the being and mission of the Church:

Though they differ in essence and not merely in degree, the common priesthood of the faithful and the ministerial or hierarchical priesthood are none the less ordered towards each other; each in its own way shares in the one priesthood of Christ. The ministerial priest, by the sacred power that he has, forms and governs the priestly people; in the person of Christ he brings about the Eucharistic sacrifice and offers it to God in the name of all the people. The faithful indeed, by virtue of their royal priesthood, share in the offering of the Eucharist. They exercise that priesthood, too, by the reception of the sacraments, by prayer and thanksgiving, by the witness of a holy life, self-denial and active charity (LG §10).

With regard to the baptismal priesthood, we read further, in Presbyterorum Ordinis,

The Lord Jesus, whom the Father consecrated and sent into the world (Jn. 10.36) gave his whole mystical body a share in the anointing of the Spirit with which he was anointed (see Mt. 3.16; Lk. 4.18; Acts 4.27; 10.38). In that body all the faithful are made a holy and royal priesthood, they offer spiritual sacrifices to God through Jesus Christ, and they proclaim the mighty deeds of him who has called them out of darkness into his marvelous light (see 1 Pet. 2.5, 9). Therefore, there is no such thing as a member who does not have a share in the mission of the whole body (§2).

· This leads to the sixth point, namely, that although the notion of co-responsibility arises out of the fundamental equality and dignity proper to Baptism, a complete account of co-responsibility cannot be developed out of Baptism or fully stated in baptismal terms, just as a complete account of Baptism itself cannot be developed out of Baptism or fully stated in Baptismal terms,[4] because Baptism itself is intrinsically ordered toward Eucharistic communion. The communio of the Church is only fully accounted for in Eucharistic terms, and this means in priestly terms. The communio that constitutes the Mystery of the Church is fulfilled in the mutually ordered relationship between the two participations in the one Priesthood of Christ. We read in the Synthesis Report that an invaluable fruit of the synodal process has been, “the heightened awareness of our identity as the faithful People of God” and as “called to differentiated co-responsibility” (§1a), but if this is true, then the language of “co-responsibility” for the being and mission of the Church is incomplete if it does not refer to the way in which these two priesthoods are different in essence and as such are ordered towards each other in the building up of the one Body, and thus generate a co-responsibility. We could say they are co-ordered to the building up of the one Body.

· This leads to the seventh point which is also the first worry: The Synthesis Report does talk about co-responsibility being exercised across a variety of “charisms, vocations and ministries” (from the Introduction, echoed throughout), but there is no explicit mention of Holy Orders as constitutive of one of these vocations and ministries. And, although the Introduction presents the Sythesis Report as an interpretation of the conciliar literature, there is no mention at all of the baptismal priesthood. Holy Orders itself is not even mentioned in the section on deacons and priests. This lack of precision and clarity gives the impression that the priesthood, here meaning the ordained priesthood, is purely functional, and not rather constitutive (along with the priesthood of the baptized) of the mystery of the Church as born from Christ’s sacrifice. As John Paul II noted, with respect to the ordained priesthood: “the ordained priesthood ought not to be thought of as existing prior to the Church, because it is totally at the service of the Church. Nor should it be considered as posterior to the ecclesial community, as if the Church could be imagined as already established without this priesthood” (Pastores Dabo Vobis §16). The impression that can be given from the Synthesis Report is that “priesthood” seems to demarcate only one among the many ministries, charisms and vocations that have their origin in the baptismal call to mission. It is distinguishable as a function and role but not essentially different in kind.

Without explicit clarification, the Synthesis document seems to teeter, unintentionally, on a Reformed understanding of ministry, where all ministry flows from Baptism, and a correspondingly Reformed ecclesiology which is essentially baptismal and only secondarily Eucharistic. In fact, it can be read, though certainly not intended this way, to verge on an account of the Church that occludes its character as Mystery altogether, in favor of a purely functional account, flatlining the Church as though it were simply a secular organization though with a holy purpose of spreading the Word of God. But, remember, evangelizing is not simply spreading the Word of God, for which one does not need a People of God or a Mystical Body or a Spouse of Christ or a Temple of the Holy Spirit. The terminus of evangelization is the same as that of Baptism, namely, full incorporation into the communio of the One Body and the One People, accomplished Eucharistically. As noted in Presbyterorum Ordinis, “no Christian community is built up which does not grow from and hinge on the celebration of the most holy Eucharist” (PO §6).

· This leads to the eighth point which is the second worry. This has to do with the idea of “synodality” itself. Inherently it is a beautiful and appealing concept intended to emphasize a leadership style that is attentive and thoroughly consultative, at least, as I read Pope Francis’s Episcopalis communio, and I am appreciative of this emphasis. But in the Synthesis Report it appears more ambiguously. Claiming that synodality “constitutes a true act of further reception” of Vatican II, “implementing what the Council taught about the Church as Mystery and People of God” (Introduction), it is described as “a mode of being Church that integrates communion, mission and participation” (§1g). In other words, “synodality” is an ecclesiology, at least implicitly, a particular theology of the Church, which claims to be a development of Lumen Gentium. What are its basic features? “Baptism,” above all, “is at the root of the principle of synodality” (§7b). Synodality claims to develop a primary feature of the ecclesiology of Lumen Gentium, namely, its recovery of the idea that all of the baptized, in virtue of their baptism, are called to contribute to the mission of the Church. Synodality “values the contribution all the baptized make, according to their respective vocations” (Introduction).

Further, “An invaluable fruit of this [synodal] process is the heightened awareness of our identity as the faithful People of God, within which each is the bearer of a dignity derived from Baptism, and each is called to differentiated co-responsibility for the common mission of evangelization” (§1a, cf. 3c). Synodality values the title “People of God” for the Church, correctly associating this title with the idea that baptism calls all to contribute to the mission of the Church. Nevertheless, as Lumen Gentium and Presbyterorum Ordinis make clear, the Church as People of God cannot be fully described in baptismal terms alone, and certainly not without mention of both of the two priesthoods that, as co-related to each other, are constitutive of the Mystery of the Church as wholly gift, derivative of Christ’s sacrifice as a Church-making sacrifice, made ever-present in the Eucharist. Without further clarification, “synodality” can thus appear, anyway, as describing, at best, a variety of Protestant ecclesiology, and at worst, an organization from which the idea of the Church as Mystery has been severely attenuated. Indeed, the notion of the Church as Mystery is mentioned only once, seemingly as an afterthought, in the Introduction of the Synthesis Report, with no follow-up anywhere in the document.

· The ninth point: A full account of co-responsibility, and of synodality itself, will therefore not ultimately be derived from Baptism but from the mutual co-relation of the two priesthoods that together constitute the Church, ordered, as they are, towards each other, and co-ordered, one could say, towards the mystery of ecclesial communio.

· And the tenth point: The theology of co-responsibility, when the two co-related participations in the one priesthood of Christ are taken into account, has the beauty of carving out two distinct, though related, spheres of leadership. There is a leadership associated with the hierarchical priesthood, that of pastoral governance, authoritative teaching, and sanctification, as clearly stated in Lumen Gentium §10. But to me one of the most important features of the theology of co-responsibility is that it indicates that governance, and participation in governance, is not the only form of leadership in the People of God.

We should resist the temptation to conflate leadership too quickly with governance, as we seem to have done before Vatican II and in fact as we still seem to do. If there is no true sphere of leadership, theologically defined, connected to but differing, in a co-responsible way, from governance, then those denied ordination on the basis of innate factors such as sex can legitimately feel aggrieved. Of course, as noted above, because it is an exercise of a priesthood derived from the priestly sacrifice of Christ, it is ordered toward building up the communio of the one Body and so cannot be exercised independently of the hierarchical priesthood, which has the same end in a complementary fashion. Dorothy Day, always ahead of her time, when asked whether Cardinal Spellman contributed to the expenses of the Catholic Worker, used to answer, “No, but he didn’t ask us to undertake this work, either.” She did not need permission to engage in the far-reaching leadership that she did undertake, though, on the other hand, though she was willing to offer pointed responses to his critique of her positions on pacifism, etc., she never disobeyed him.

There are so many examples now of lay-initiated and lay-led projects of evangelization intended to build up, in one way or another, the communio of the one Body. This is not governance. As already noted, not any old project of evangelization is a true exercise of the baptismal priesthood and certainly projects involving imprudent or heterodox teaching are subject to the correction of the bishop—that is part of his co-responsibility. Nevertheless, it is genuine leadership and in many cases this leadership is trend-setting for the Church. As Pius XII famously said, the laity are on the front-lines of the Church’s mission (see CCC §899).

· The eleventh point, is coincidentally the third worry: To the extent that “synodality” is synonymous with “baptismal,” it will regard all the ministries of the Church as differing, perhaps, in degree, but not differing essentially, in kind. This differing only in degree will include the governance which Lumen Gentium (§10) taught was intrinsic to Holy Orders, especially that conferred on the bishop (see: LG §21, “The fullness of the sacrament of Orders is conferred by episcopal consecration . . . [which] confers, together with the office of sanctifying, the offices also of teaching and ruling,” forcefully and further specified in LG §27). But if “synodality” is synonymous with “baptismal,” then it will seem that governance is essentially a baptismal charism, vocation or ministry. But then co-responsibility for the mission of the Church, coming exclusively from Baptism, can begin to be synonymous with co-responsibility for governance. If co-responsibility and the various charisms and ministries that are to be co-responsible for mission, flow from Baptism, then there is need of a wholesale reform of Church “structures,” and the Synthesis Report seems to call for such:

All the baptized are co-responsible for mission, each according to his or her vocation, competence and experience. Therefore, all contribute to imagining and discerning steps to reform Christian communities and the Church as a whole, [and] . . . this co-responsibility of all in mission must be the criterion underlying the structuring of Christian communities and the entire local church . . .

So that “each member is involved in processes and decision-making for the mission of the Church” (§18a-b). Co-responsibility for mission here seems nearly indistinguishable from co-responsibility for governance, and “synodality” seems almost to mean, “co-responsibility for governance.” The laity, it could seem, are truly co-responsible for the being and mission of the Church only to the extent that they are co-responsible for governance, at least in a reformed ecclesiology that flows principally from Baptism. But unless baptismal synodality means the erasure of the intrinsic connection between Holy Orders and governance—and surely the Synod does not intend to reject outright the teaching of Lumen Gentium and Presbyterorum Ordinis—this means that any leadership exercised co-responsibly by the laity will be exercised principally as part of a leadership ministry that is different in kind from their own, a clerical ministry properly speaking, rather than one that is truly their own.

It is true, of course, and good, that lay people can and do participate in structures of governance, even as Chancellors in dioceses or heads of Roman dicasteries, but in these positions they are collaborating in a leadership ministry which is essentially that of the hierarchy, which is not essentially their own. It is also true that all the faithful share in the three munera of the priesthood of Christ, but no lay person, by definition, will ever govern the universal Church, a diocese, or even, strictly speaking, a parish.[5] If the governance intrinsic to the fullness of orders is the only form of true leadership in the Church, then leadership and governance seem to be conflated again, just as they were before Vatican II.

But the laity do not need a structure or pastoral plan to validate or mandate the leadership that comes with the exercise of the baptismal priesthood in evangelization. Baptism is itself the mandate. The “synodality” envisioned by this document, in erasing the very language of the baptismal “priesthood,” which establishes a true sphere of leadership proper to the lay faithful imparted by the mystery of Christ’s priesthood present in the Church, could seem then to be just a renewed form of clericalism, where there is never any true leadership that pertains uniquely to the priesthood of the baptized, any true sphere for lay leadership in the Church.

· Finally, the twelfth point, including the thank-you: I offer these comments hoping to contribute to the synodal journey, and especially to episcopal discernment regarding the relatively new phrase, “co-responsibility.” I offer my comments in the spirit of the Synthesis Report itself, which clearly states that it is “not a final document, but an instrument at the service of ongoing discernment.” It is intended to “orientate reflection” regarding points on which “it is necessary to continue deepening our understanding pastorally, theologically, and canonically” (Introduction). The invitation to theological deepening in particular is especially prominent throughout the document. I have taken this invitation seriously and at face value, hoping to offer something where I think, as in any document still in development, enhancements seem needed. It was truly a gesture of the synodality of which the Report speaks to publish a document like this, open-ended and still under construction, and to invite such comment. I admire this commitment to openness and hereby express my thanks to those responsible.

[1] In the article from The Thomist, cited above.

[2] Translations from the documents of Vatican II are taken, sometimes with adjustment, from Vatican Council II: Constitutions, Decrees, Declarations, edited by Austin Flannery, O.P. (Northport, NY and Dublin: Costello Publishing Co. and Dominican Publications, 1996). The adjustments are sometimes my own, and sometimes, especially for Lumen Gentium, taken from the official English translation at https://www.vatican.va/archive/hist_councils/ii_vatican_council/documents/vat-ii_const_19641121_lumen-gentium_en.html

[3] Or perhaps, more precisely, the Church, in Christ, is the sacrament of this fellowship.

[4] This is perhaps implicitly recognized at sec. 3g of the Report.

[5] For example, of no layperson will it or could it ever be said that “by the authority and sacred power which they exercise exclusively for the spiritual development of their flock … bishops have a sacred right and duty before the Lord of legislating for and of passing judgment on their subjects, as well as of regulating everything that concerns the good order of divine worship and of the apostolate,” no matter how synodally this authority is exercised (as it should be).