I have heard it said that philosophy is safe because it is not political, that it is unwarlike. Sometimes this is asserted because philosophy is seen as a safe haven, away from the dogmatism of religion, or at other times, in the belief that the pristine realm of reasoning leaves the world untouched. Presumably, philosophy is safe from violent or political contention for as long as it does not embody itself in peoples’ everyday rituals and practices.

Such an idea depends on the notion of the non-reality of ideas, or else on the perpetual postponement of their instantiation. But are these not fantasies based upon outdated theories of truth? In what follows, I will explore an alternative theory of truth which in no way resorts to truth as residing in a pristine interior, and which allows our human actions and interactions to be in the path of the truth.

I have argued elsewhere that truth is not a matter of reference but of addition. In his early dialogue, Laches, Plato reports Socrates as saying: “For if we know that the truth of something would improve some other thing, and are able to make that addition, then, clearly, we must know how that about which we are advising may be best and most easily attained.”[1] The improvement in this case is virtue. For Plato, this is a matter of pursuing the Good which can only be known through contemplation of Truth. Eternal truth radiates forth towards one as Beauty, which in turn incites one’s desire to pursue the Good as one’s true end.

Surely Plato, following Socrates, was right. Truth, if it exists, cannot be something evanescent. It must be eternal, even though it is ultimately unknown. One must, moreover, assume by a kind of faith and trust that eternity is not nothing, or an indifference of being, but is eternally expressive or emanative, both within itself and outside itself, as the manifestation of all finite things; even if, for the simple and infinite One, this is eternal, these two aspects cannot be separated.

For one to be able to believe that there is truth, rather than a redundant mental reiteration of being, one must believe that eternity involves an addition, yet without departure or subtraction from itself: a “repetition” that is 1x1 =1 and not 1 +1 = 2, as Thierry of Chartres after Boethius reasoned, when trying to explain the Trinity.[2] In the divine infinite, one has to trust, there resides an infinite expression which is guided back and forth within the One by an infinite spiritual lure of desire, with infinite beauty mediating the whole. Not just beneath the level of the One, which would subordinate truth, but Within and as the One, there obtains the intelligent and the spiritual or psychic, as the Neoplatonist Porphyry intuited, and Christian Trinitarian reflection confirmed.[3]

For human beings, truth is inaccessible and unknown. If it is possible for one to know such truth, then it must be a matter of participation in the eternal, and of faith that such participation is possible, because it can never be demonstrated. As Dariusz Karlowicz argues in The Archparadox of Death:

If we accept that there is no starting point that could offer an infallible certainty and obviousness (along the lines of Stoic graspable notions), then we must agree that so long as we do not participate in perfections, then we are condemned to opinions.[4]

The perplexing character of the Socratic path, the Western path to truth, is that it embraces skepticism as to one’s finite predicament in the face of truth, and yet it refuses to be content with merely sophistic opinion. A further perplexity is that Socrates appears to overcome mere opinion in two apparently contradictory ways: first, by the mediations of dialectic, and secondly, by way of a visionary immediacy which is internal and incommunicable. Only the gesture of irony seems to link these two ways.

In Laches, Socrates understands daily persistence in argumentative investigation of one’s life, without which he famously says that life is not worth living.[5] It is a mode of the exercise of andreia or courage.[6] This term in Greek means “manly fortitude,” and has a close affinity with thumos, the middle part of the soul in Plato’s Republic, the element which exercises control over one’s passions.

One might exhibit and sustain such a human—as one can now expand—fortitude, in approaching the enigma of truth from several fan-like vantages, or aspects, rather in the way that Socrates seems to begin each new day with an apparently random starting point. And as with a Platonic dialogue, one may cite many different heroes and heroines of philosophy who have contributed, as much by negation as by affirmation, to unveiling this enigma, though one can only do so by encountering further veilings and enclosures.

These witnesses enable one to realize that there is no final truth of even finite things. Because everything is self-additive, and truth is expressively inherent to them, they will not yield their final truths, or what they are in their inner-substantive core, as Christian Church Fathers, from Gregory of Nyssa to Eriugena, proclaimed, in offering a negative ontology.[7] Things, moreover, like causes and motions, exhibit a final incoherence, suggesting an inner emptiness. Apophasis is here compounded by aporia.

This emptiness of finite things either indicates an ultimate emptiness and non-truth at the core of reality, or it points to the inner emanative and creative constitution of things by eternal mystery, whose own emptiness may indicate its boundlessness and incomprehensibly unconfined plenitude. One must have faith in the latter, and one’s participation within it, if one is to believe that the additions made by things, and by subjective things, arrive at an inkling of the truth.

One may suggest that spiritual beings are the emptiest of all, and round upon their own being in an empty reflexive gesture. But this lack of content is an openness to, and opportunity for the embrace of an infinitely varied content. Furthermore, this embrace, as the formation of positive habit or non-identical repetition, proves capable of establishing definite—although definite because elusive—“character” or “style,” more so than ordinary things which lack subjectivity, or possess it in weaker degrees.

As we have already implicitly concluded, the debate concerning truth revolves around the question of subjective expression. It transpires that one is not dealing with the issue of, “how can one think truth?” Rather one is led to the affirmation that psychic intelligence, or “thinking,” is not the site, but the continuous event of truth in its expressive occurrence. It is when thought is distorted, when it is “un-thought,” that one has falsity or lack of truth, though, beyond trivial instances, one has no way to detect these flaws, save through a combination of the patient and courageous exercise of dialectic with an immediacy of discernment and aesthetic judgment.

The Socratic conclusion of every dialectical path is into this silence and interiority: truth reigns within as one’s inner vision of encounter with the absolute. His defense before the city was not simply in the name of an exercise of reason against the authority of tradition, and the supposed oracles of the traditional gods. It was indeed these, but it was also an appeal to his daimon, to a semi-divine voice within himself, and to an explicitly prophetic conviction that his witness would outlast the destruction of the city, as has proven historically to be the case.[8]

But how can such immediacy of truth, of inward encounter with the divine beyond argument, be anything other than inscrutable? The Platonic dialogues provide the answer. Socrates’s truth beyond dialectic would be withheld if he were not, in his own life, and in his conversation, in his body and his actions, a witness to his immediate inner and partial vision of the truth which he declares belongs to the unknown God. But this is not to abandon argument; it is to live in harmony with all that one’s true arguments indicate.

In the eponymous dialogue, Laches the military general evokes Socrates as “a true musician, attuned to a fairer harmony than that of the lyre, or any pleasant instrument, for he has truly in his own life a harmony of words and deeds arranged.”[9] To live in this “true Hellenic mode” of the Tetrachordic Dorian is to proffer one’s life as itself a more complete argument. One can here emphasize the bodily and existential performance of verbal truth as essential to its evidence and further articulation.

If living well demonstrates truth beyond argument, then courage is extended beyond debate to the conduct of one’s life. The ultimate courage needed, as eventually exhibited by Socrates, is to be prepared to die in defense of the Truth, and of one’s own subjective witness to that truth, even though this subjective experience cannot be fully communicated, as Kierkegaard elaborated. A doubled intimacy between sophia and andreia ensues, and this is the stake of Laches. The sophist Nicias parodies wisdom and yet comes close to it, and so to “philosophy,” when he argues that wisdom simply is courage, which is equivalent to a reduction of nous to thumos.[10]

It has already been established in the dialogue that courage must be distinguished from folly, though this problematically seems to rule out the undertaking of hopeless military defense, which is for our intuiton the most courageous thing of all.[11] Courage has also been distinguished from endurance, which might apply to the patience of the person who is merely thrifty with his money.[12] So Nicias seeks to equate true courage with a true knowledge of “the fearful and the hopeful,” which suggests a utilitarian orientation.[13]

But Socrates does not altogether question this temporal slanting of wisdom, but suggests that the person of true courage would judge also the past and the present in terms of what is to be avoided and what is to be looked for. The dialogue reaches an inclusive aporia when Socrates says that, in that case, courage is the entirety of virtue, though he has persuaded Nicias to concede that other virtues are of equal importance, such as justice and temperance.

One is left to infer Socrates’s solution, since he leaves courage undefined. This undefinition suggests that it overlaps with the unknown Good, True and Beautiful, though in a “transcendental” way that does not deny the pervasiveness of other transcendental aspects, such as justice. Univocity lurks in the sophistic position, which implicitly assumes that what is to be feared or hoped for is obvious; danger to self and success for self, and so forth. But as soon as one asks what is to be properly feared or hoped for, then justice and the like come into the picture, alongside fortitude.

Nevertheless, one takes it that the mark of persistence is the mark of eternity, and if the latter is perforce subjectively witnessed to, then the feeling of persistence, and of an inexpressible cleaving, is integral to one’s truth as such. And this truth does indeed prophesy. In a radically marred or “fallen” world, subjective witness must be unto death, unto martyrdom in the face of the city’s refusal of the truth. It would seem to be any sort of real martyr who can exhibit a hopeless courage which remains courage, and who has both practiced beforehand, and yet cannot have practiced his own ultimate bravery.

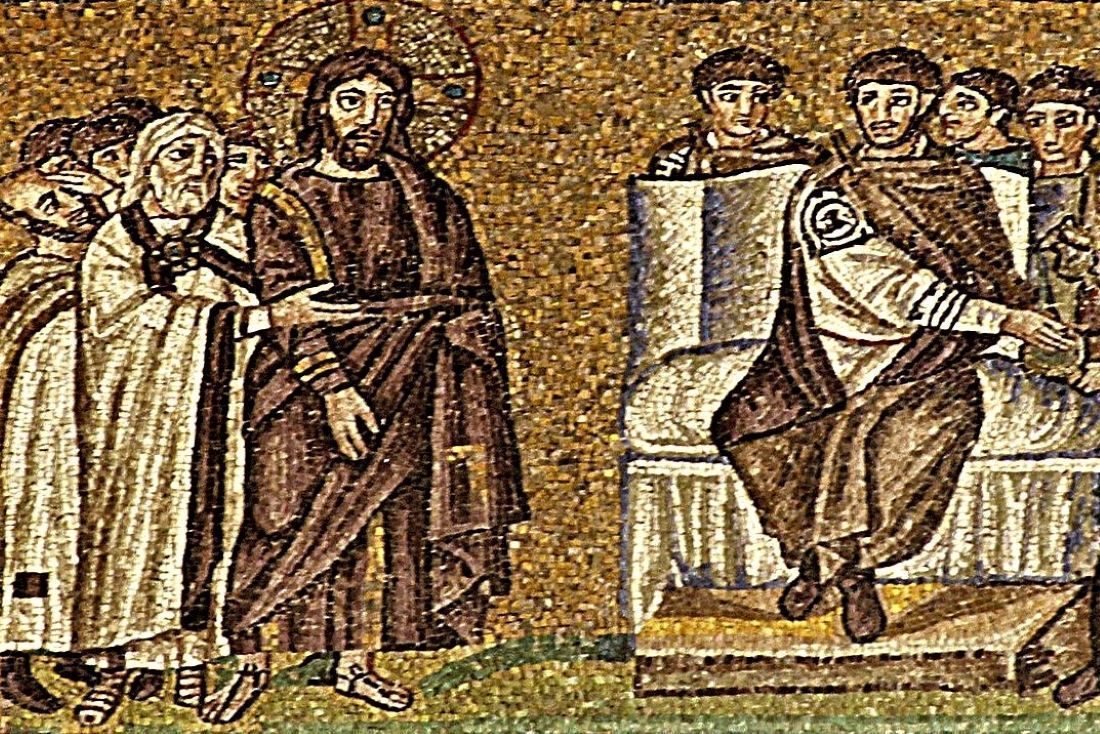

And yet this insistence upon an immediacy that fades into the disappearance of death is not Socrates’s or Plato’s only word concerning truth. As Karlowicz points out, the “archparadox of death” is that the martyr herself testifies beyond any mediating argument or education by the other, and yet herself becomes the mediator, the argument, if she is persistent in loyalty to a good case and a good cause, rather than a false one.[14] This is true of Socrates; and supremely of Christ, whom the seventeenth century philosopher Anne Conway argued was needed to consummate speculative metaphysics with a monadic event, and to mediate between the infinite and the finite.

In this way, death within and against the city is returned to the context of the city, and sets up a new chain of civic witnesses to, and mediators of the truth. Neither Socrates nor Christ despises the gods, laws and truths of the city, even when they have become so distorted as to turn against their witness to a more ultimate truth. In one sense, Socrates declares, there is something more ultimate than one’s homeland, but in another sense, there is not, because only this homeland has allowed one to participate in the universal.[15]

The mediations of the finite that are but partial truths must be included and redeemed within the whole truth, otherwise it remains partial, even, as we can say, beyond Plato, in its “infinity.” Socrates is bound to die within the city, and under its laws, if he is bravely and honestly to bear witness to that which transcends the city, and upon which it is based. Here lies a further archparadox.

Laches pivots upon this tenson between the immediate and the mediated. Does one need a teacher to guide one into the addition of virtue? Does one need to practice fighting with armor if one is to prove oneself brave in battle, or will this render one too cautious, bravery being a matter of pure spontaneity? A triad is implied between the teacher, exercise, and the real occasion of performance. Socrates seems, as immediate bearer of the logos, to escape this triad: he is apparently untaught and his daily exercise of dialectic is an unpracticed performance.[16]

Yet one knows that he is instructed from within, has been rehearsing dialectic since youth, piously sustaining by name and by repute the legacy of his father, and that he acknowledges the city as his instructive nursing-mother.[17] Nonetheless, he has laid claim to an immediate familiarity with the divine, in such a way that even fathers will now submit to his instruction.

As also with the martyr-figure he is soon to become, however, this incites a new and alternative chain of civic mediation: Socrates, himself once a hero in battle,[18] now instructs the sons of soldiers in the wisdom of courage and the courage of wisdom.[19] They will undergo practice in the art of dialectic, which will prepare them for the real witness of their lives. It is as if this account of andreia, or Latin virtus, anticipates the Neoplatonic triad of ousia or essence, dynamis, virtus, or power, and energeia, or operation, which will be adopted by Patristic and Medieval Christian philosophers to explicate the Trinity.[20]

Unity or being is the eternal source, and truth the eternal addition, eternal preparation, eternal courage for the expressive performance of the Good. Unless one bravely shares in this consistency, one cannot bring the truth-bearing cosmos to its final peaceful fruition.

[1] The present essay is based on the post-script of my book, Aspects of Truth (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020). See: Plato, Laches, 189e 1-5

[2] Boethius, De Institutione Arithmetica; Thierry of Chartres, Lectiones in Boethii Librum de Trinitates III, § 2. Pseudo-Bede and Alain of Lille make similar points, later taken up by Nicholas of Cusa.

[3] See Pierre Hadot, Porphyry et Victorinus (Paris: Études Augustiniennnes, 1968), 79-145, 309-312.

[4] Darius Karlowicz, The Archparadox of Death: Martyrdom as a Philosophical Category , trans. Artur Sebastian Rosman (Frankfurt-am-Main: Peter Lang, 2016), 245.

[5] Plato, Socrates’ Apology, 38a 1-5.

[6] Laches, 194a 1-5.

[7] Denise Carabine, ‘John Scottus Eriugena: A Negative Ontology’, Negative Theology in the Platonic Tradition: Plato to Eriugena (Louvain: Peeters, 1995), 301-322.

[8] Socrates’ Apology, 39c-e.

[9] Laches, 188d, 3-9.

[10] Laches, 194d-e.

[11] Laches, 193b-d.

[12] Laches, 192e 1-4

[13] Laches, 193a 1-3

[14] Karlowicz, The Archparadox, 241-252.

[15] Plato, Crito, 51a-c.

[16] Laches, 186c 1-4.

[17] Laches, 181a 1-5; Crito, 51a-c.

[18] Laches, 181b 1-4.

[19] Laches, 181b 1-4.

[20] See, for example, John Scotus Eriugena, Periphyseon I. P. Sheldon-Williams ed (Dublin: School of Celtic Studies, 1999), I, 486 c-d, page 137 and n. 144, page 237.