When I was in grade school, the whole idea of having a vocation seemed rather clear to me: I learned that I had a vocation either to the priesthood or to marriage, and that was it. Anyone not choosing to be a priest (or brother) or a nun was definitely not taking the high road, in some way being less than generous with God or failing him somehow, but marriage was still an acceptable option. We had the choice of a moral life in the standard married state or in the deluxe consecrated life. No one really talked about why there was a difference in value between the two acceptable states, but it was clear that anyone not choosing one or the other of these states of life was somehow a moral shirker.

Once I had met the young Jesuits teaching in my high school I chose to become a Jesuit, and becoming a priest was simply one way of living that life. I am certainly grateful for that, but over the years I have tried to understand the whole process of God’s call to each of us, not just to some sort of commitment, consecration, or ordination, and that has led me to consider a whole series of elements in God’s creative call.

First, I will look first at a very simple analysis of what the synoptic Gospels tell us of Christ’s gathering disciples to himself, especially those who became the Twelve. Second, I will consider John’s Gospel.

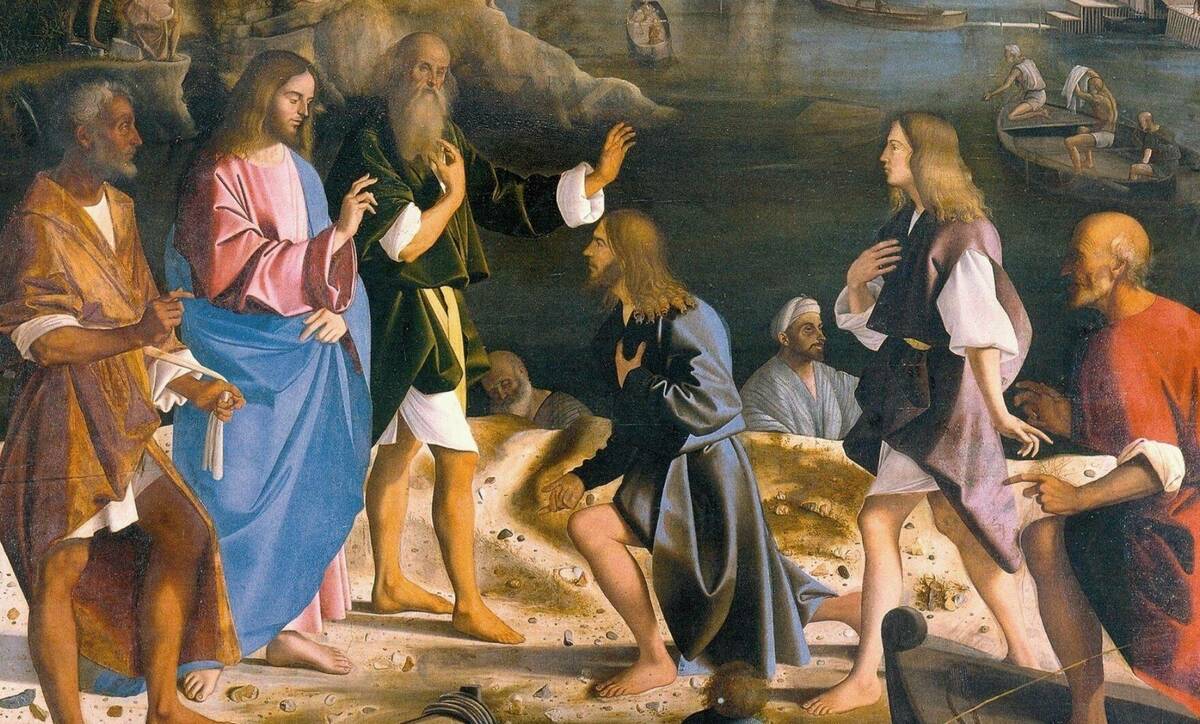

Matthew describes the call of Peter and Andrew, then of James and John, and finally of himself (Mt 4:18–22; 9:9), then he suddenly lists the names of the Twelve (10:1–5) without detailing the calling of the other seven. It would seem that Jesus had a number of people following him and believing in him, and he simply chose twelve out of that group. If so, that would seem to blur the meaning of “disciple,” distinguishing between the inner Twelve and the less dedicated believers. In Matthew 10:5–42 Jesus sends his Twelve out with instructions on how to be his missionaries, and he later gives Peter a special status as the “rock” on which he will build the Church (16:18). Matthew ends with a ringing mission to go and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them “in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit” (Mt 28:18–20).

Mark’s Gospel appears to be much simpler. He recounts the same call for the same five men Matthew does (Mk 1:16–20; 2:13–14), but Mark’s naming of the Twelve (3:13–19) reveals more clearly the sort of double level to discipleship that I suggest above. Jesus calls the Twelve into the hills, and Mark lists their names. Jesus sends the Twelve out in pairs (6:7–13), something Mark’s Jesus does not do with any of his other disciples, and he gives them some instructions. Mark also has the story of the rich young man (10:17–22), and he ends with a missioning similar to Matthew’s, but he is less pointed and more detailed (16:16–18).

Luke’s account is somewhat different. Jesus heals Simon’s mother‑in‑law (Lk 4:38–39), then borrows Simon’s boat to preach from, commands Simon to cast the nets out for a great catch, and finally declares to Simon, “I will make you fishers of men” (5:1–11). This seems to cover only three of the men fishing (Simon, James, and John), and then Luke adds the call of Levi (5:27–28). Jesus names the Twelve (6:12–16), then in 9:1–6 he confers power and authority on them and sends them out to preach the Kingdom and to heal, giving them instructions on their manner of proceeding. Finally Christ sends out 72 others, giving them their own instructions (10:1–12, 17–20). His final words before the Ascension (24:44–49) are not a missioning and do not have a direct link to the idea of vocation.

We might summarize the synoptic approach as having three stages: generally speaking, men are attracted to what Jesus says and does and to who he is, and in a second step they follow him rather seriously. Jesus finally calls some of these men by name to follow him, giving them authority and power and sending them out to continue his work.

Notice, however, that Luke also includes a list of women who responded to Christ and followed him (8:1–3). They “cared for him” (laundry? food?), but they also did more than that. They followed him as disciples. Matthew (27:55–56) and Mark (15:40–41) barely touch this topic, and John (19:25) is concerned about something completely different.

Indeed, the whole Gospel of John is a rather different matter—our second view of vocation. Similarly to the synoptics, people believe in Jesus because of his signs as well as his words (Jn 7:46), but John adds an extra element: for John, certain people—both men and women—encounter Jesus and are so changed by the experience that they must run and share their discovery of who he is, thus bringing others to know and believe in him. The initiative is more clearly theirs than in the synoptics. Jesus will say that he chose them (Jn 6:70–71; 15:16), but I do not consider that contradictory: he chooses all of us, and he has hopes and plans for each of us, yet he also leaves our response completely up to us.

The most noteworthy passage demonstrating this “run and tell” sequence is in John 1:35–51, where Andrew, an unnamed disciple, Philip, and Nathaniel encounter Jesus. It is worth pointing out that John does not speak of exactly what happened when Andrew and his companion get acquainted with Jesus; what catches their attention and makes Jesus so attractive to them is private and personal.

Again, somewhat similar to what the synoptics do, John shows Jesus missioning his disciples (Jn 17:18; 20:21–23), but this missioning also appears in filigree (13:1—17:26). John’s Jesus grants them certain powers as he sends them out (20:23). And while Jesus does choose certain men (6:70–71; 15:16), we never see him doing so. One thing that John most notably does not do is to include a precise list of who the Apostles are, and this seems important to me for reasons which will become clear below.

I think that we can say that John’s approach to what we now call a “vocation,” that special but today somewhat institutional relationship to Christ, is generally similar to that of the synoptics yet is more nuanced and far less clear-cut in the forms it takes. John does not list those who hold an official role among Jesus’ followers, but it is fairly clear who those men are.

In John’s Gospel, Mary Magdalene seems to have a closer relationship to Jesus than some of the Twelve do; she certainly seems to be with them in much of what they do. Even within a cultural context which limits the status and function of women, she seems to be a high-profile member of Jesus’ followers, which seems to be based first on having a close personal encounter with Jesus and then on choosing to be his disciple. The upshot is that, while the Apostles are certainly male in John, he puts far less emphasis on gender and more on the individual form and depth of the person’s response to the Lord. The Christian community implied by this approach is far less hierarchical and is much broader in gender inclusion.

A third view of vocation, one which encompasses far more than a call to an institutional and often sacramental role in life (and I include all the possibilities here, including marriage), is closer to John’s views and is based more on God’s love for us, his respect for us, and the wealth of possibilities he offers each of us.

In considering this approach. I think that it is important for us to pay attention to the fact that we live in a culture that has been nominally Christian for centuries, with the result that we think that we know Jesus, who he is, and what he wants and offers. We also carry, as part of our cultural baggage, an awareness of the immense variety of people who call themselves Christians. Both of these can be a real hindrance to meeting Christ, since if we think we already know and understand Christ we have little motivation to grow in that knowledge or in our relation to him. At the same time, the diversity of those who call themselves Christian can lead to a confusion, since they disagree with each other and often enough lead lives that are hardly attractive to seekers of the true Christ.

There are, however, some special people who stand out as true followers of Christ. These people have something about them, explicitly or implicitly, that says that they know Christ well and that they are people of real and frequent prayer. It is also clear that these people love the lives that they lead and that they value the treasure that is in their hearts. They share their lives with others who resemble them in all of this. This is true for many who have chosen the religious or priestly life, but it is just as true for those who are married and live their lives in Christ.

Many of those who look on such special people realize that they also wish to know Christ better, as these people do, and possibly to know him in a different manner than they currently do. The first step in doing so is to find someone whom they can trust absolutely and who is wise and willing to work with them, and then begin to learn from that person how to pray or at least how to pray differently. This will include working with Scripture, practicing a certain ascetical effort, and exercising patience and humility, and the spiritual guide will help the searcher to discern just what is happening in his or her life and prayer.

Now I believe that God has given each of us an identity composed of when, where, and in what circumstances we come to life, not only at the moment of our birth but in all of our days on earth: who are our parents and our siblings? What seeming advantages or disadvantages do we have? What are our gifts and weaknesses? Absolutely everything that we are and all that happens to us is the intentional gift of a loving, wise, and all-powerful Father; every bit of that is an opportunity for us to respond to him, whether it be in service, in gratitude, or in overcoming our limitations. Certainly this is where we must begin our prayer, for this is who we are.

God asks us to choose who we will be in terms of these gifts, which ones we will decide to make particular use of in knowing, loving, and serving him—and we do need to choose, since our Father is prodigal in the talents and opportunities that he bestows on us. We cannot use every one of his gifts to any great degree, because time is one thing that we do not have, so we must decide which ones we will choose, use, and develop to define who we are. To truly become the persons that we wish to be and whom God invites us to be, we must approach God in prayer most humbly, asking him to tell us what he thinks of our possible choices, praying, “your kingdom come, your will be done” in us just as it is in heaven. The Spirit will help us to recognize and understand the motions of our hearts, for indeed the Spirit is itself at the origin of those motions.

There is a need in God’s Church and in his Kingdom for people to play many roles:

To some his gift was that they should be apostles; to some, prophets; to some, evangelists; to some pastors and teachers, so that the saints together make a unity in the work of service, building up the Body of Christ. (Eph 4:11–12)

Here is where God shows his respect for us, allowing us to have a real voice in who we become, and in doing so we participate (in a subsidiary and derivative manner, of course) in God’s own creative activity.

Making this choice is where the spiritual director or guide is of prime importance. We will never make a perfect choice, and we will always alter that choice later in ways that are sometimes small, sometimes significant, but hopefully always in ways that help us grow in the Lord. Yet, we do need to make some sort of fundamental decision about who we wish to be, both interiorly and for our role in life. We cannot afford to simply drift our way along.

Most of us train professionally for a long time before we begin our career or life’s work, and that training is or should also be a process of ongoing discernment as to whether we fit that choice and vice versa. Once we become priests, for example, we have little in the way of moral choices as to whether we can stop being and functioning as priests, but doctors and dentists commit themselves almost as seriously to their own professions. Whatever path we choose, we need to be clear as to what we are undertaking.

Once we have made that fundamental choice, however, we still need to keep changing and growing: God’s gifts are simple, but they also have all sorts of aspects and levels to them. One might be a fine priest, for example, and still feel drawn to work in social justice, and even then that might mean teaching it or working for it on the parish or diocesan level, or spending time abroad with people one might work with and learn from. We need to develop ourselves continually, to be present to ourselves and to God at the same time, and to discern where God is leading us in our chosen life today. Again, a spiritual guide can be of immense help here.

But there is an additional aspect to all of this. Most of the time we are already doing good things, but we may still feel a stirring of dissatisfaction—an itch to do more, to do better, or to just do other. Ordinarily that leaves us right where we are and we develop in place, growing wiser and more broadly competent at what we do, but we certainly have examples of God entering people’s lives and indicating most forcefully that he has other desires for them than what they think, so we must be ready at all times to follow these promptings of the Spirit.

The Lord called Moses to a completely new sort of life when he was married and an established shepherd (Ex 3:1–10); David was also a shepherd when the Lord called him (1 Sam 16:1–13). Both men remained shepherds, but each in a new, special, and highly personal way. The same is true of Isaiah (Is 6:1–13), Jeremiah (Jer 1:4–10), and Ezekiel (Ez 1—2:10), for they and the other prophets indicate that being a prophet was not their idea but quite literally a call from God—his choice and sending, a development that radically changed their lives and how people treated them. Would God enter our lives today in such a peremptory and indisputable fashion? And was it for some of these men more a matter of opportunity and discernment than a nearly visible intervention, a life choice just handed down to them in a more concrete narrative form?

Jesus himself apparently thought that he should lead his life in teaching in the Temple (Lk 2:41–52), but his parents changed his mind about that rather directly. To judge from the form of his preaching as he begins his public life in Mark, Jesus had some fairly clear ideas about what his role was, something much more along the lines of what the Baptist was doing, until his own baptism and the discernment he did in the wilderness immediately afterward (Mk 1:1–13). It then took Jesus a while to develop his ideas and style. There is more than a hint that the Transfiguration was not only a revelation to the disciples but was possibly, even primarily, a revelation to Jesus of what his life was going to involve: he doesn’t really start foretelling his Passion and Death until after this point (Mk 9:1–8, also Mk 8:31–33 and 9:9–11; cf. also Lk 9:28–36).

The Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are always calling all of us to life, but few of us listen attentively. Those who do listen have often already made a fundamental life choice, but all of us who try to listen to God have a whole range of further possible choices, much more than the simple choice between religious consecration or marriage that I saw as a boy. Vatican II has opened up all sorts of roles for lay men and women in volunteering at home and abroad, in being a significant part of the parish team, in working with food banks or political reform, and even in being national speakers and organizers in their own right. Priests and religious, at the same time and for the same reasons, are also rethinking what their lives can be; this can be a real challenge as well as an opportunity.

God’s call to us today is not formal, as in the synoptics, but it is a matter of a personal and ongoing relationship with Christ, a call to constant growth, moving in diverse and sometimes unexpected directions.

In the circumstances of our coming into this world, the Father offers us all that we will ever need to come to the full stature of the Christ (Eph 4:13), and offers the gift of the Spirit to aid and guide us in our growth. Our part is to cooperate actively in this creation of who we will become. As St. John reminds us, “We are already the children of God, but what we are to be in the future has not yet been revealed.” (1 Jn 3:2).

Anyone claiming a vocation experience today in the form like the Apostles’ calls in the synoptics would likely draw attention to him- or herself, perhaps even invite serious psychological evaluation (if the vocations director did not simply dismiss the person immediately). If, however, he or she were to come and speak of hearing a call in the intimacy of prayer over a period of time, somewhat in the manner of John’s Gospel, that person would be not only acceptable but would almost certainly be welcomed.

Every vocation story is unique, but today every story is more interactive and more subtle than the synoptics make Christ’s approach appear to be. These stories often begin with meeting someone who has met God and has learned to follow Christ, and they become a continuously developing and lifelong conversation with God. Whatever form that interaction takes, it always starts with a close and prayerful relationship with the triune God, who always seeks to draw each of us to the fullness of life.

We all have a vocation, a calling, but what we sometimes forget is that we are personally involved in the response on every level. Choosing our way is not simply one question or call from God and our single response; it’s not a matter of negotiation with God, but a conversation that should last our entire lives. It is a constant growth in insight, understanding, service, freedom, and love—love of God and love of those whom we serve in living out our call.