The Supreme Court’s reversal of Roe v. Wade was probably the most exciting achievement for the pro-life movement in the last half-century. But to save unborn lives, more may be needed than merely the abortion prohibitions that this decision has allowed states to implement. This, at least, was the conclusion of some pro-lifers before Roe v. Wade—a time when there were hundreds of thousands of legal abortions, even before the Supreme Court had weighed in on the issue.

In early January 1973, about two weeks before the Supreme Court issued its decision in Roe v. Wade, members of the North Dakota Right to Life Association braved the winter chill in Bismarck to attend a conference on pro-life strategies for the future. The previous year, there had been more than 500,000 legal hospital abortions in the United States, largely because New York offered legal hospital abortions to residents and non-residents alike and California offered Medicaid funding for the procedure. Abortion was still illegal in North Dakota and most of the other states in the Great Plains and Midwest.

But at a time when any woman in her first or second trimester of pregnancy who could find a way to travel to New York could get a legal abortion, North Dakota pro-lifers knew that state abortion restrictions would be inadequate to stop abortion—let alone create a national culture of life. In a situation where obtaining a legal abortion was as easy as crossing state lines, what could the pro-life movement do to encourage women to choose life and carry their pregnancies to term?

An expanded social safety net could provide the answer, the North Dakota pro-lifers believed. What was needed was “health insurance for unwed mothers,” “subsidized adoption,” and government-funded daycare, they said at their conference. Before they could embark on their program, Roe v. Wade interrupted their plans.

In response to the ruling, which pro-lifers viewed as a travesty of justice comparable to the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision more than a century earlier, supporters of constitutional rights for the unborn launched a national campaign for a constitutional amendment that would protect human life from the moment of conception. For the next ten years, nearly every pro-life organization, regardless of whether it was led by conservative Republicans or liberal Democrats, made the Human Life Amendment its highest priority.

And when that campaign failed, pro-lifers in the 1980s turned their attention to a more politically realistic goal: using conservative judicial appointments to change the ideological composition of the Supreme Court in order to overturn Roe v. Wade. Even some of the most politically progressive pro-life activists considered the reversal of Roe v. Wade so important that they decided that lobbying for expanded maternal health benefits to deter abortions would have to take second priority.

Pro-lifers believed they had a good reason for focusing on legal prohibitions rather than social policy: they thought that laws set a social standard of justice that affected personal behavior. Just as the civil rights movement had made a change in constitutional interpretation and national law a central goal, so the pro-life movement made constitutional protection for the unborn its chief aim. And over time, as Roe v. Wade itself became the chief focus of the movement’s ire, the reversal of that court ruling (even without a constitutional amendment) seemed to them to hold the greatest promise of achieving a “culture of life.”

But perhaps in the process, they overestimated the degree to which a reversal of Roe would accomplish their goals. A Supreme Court decision reversing Roe v. Wade has taken far longer than many pro-life activists expected in the 1980s, but after decades of waiting, the moment that pro-lifers have long prayed for is finally here. Yet, the results of this reversal will probably reveal the limits of pro-lifers’ strategy more than its success. Over the next few months, we may see abortion bans in more than twenty states, but those bans will likely affect fewer than fifteen percent of the abortion providers in the United States.

This is because nearly all of the states that are poised to prohibit abortion had already made abortion difficult to access even before Roe was overturned—which meant that abortion rates were already low in those states and few abortion clinics were in operation. The end of Roe may decrease the abortion rates in those states a little more, but those gains are likely to be offset by expanded abortion services in states where the vast majority of abortions were already occurring. The existence of the abortion pill (which already accounts for the majority of abortions in the United States) will make stopping abortion through regulation alone even more difficult.

There will be no comprehensive protection of the unborn in public law across the United States. Instead, we have only returned abortion policy to the place where it was in 1972, when New York’s willingness to provide elective abortions for anyone who could travel to a hospital there made state prohibitions on abortion relatively ineffective. That is a far cry from the culture of life that pro-lifers of the time wanted to create.

Perhaps, then, the moment has also come to revisit the political priorities that many pro-life activists, including those in North Dakota, had immediately before Roe. If we want to see substantial reductions in the number of abortions in the United States, we will need to address the root causes of abortion—not simply prohibit the procedure itself in some areas.

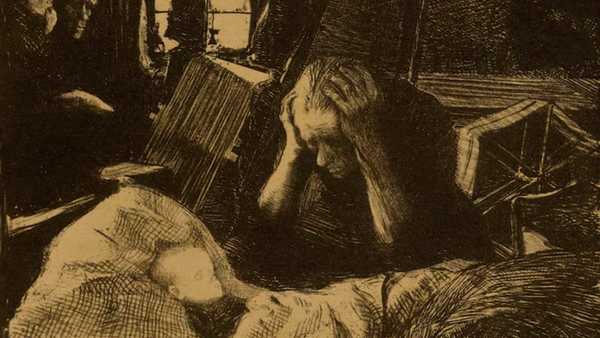

As many pre-Roe pro-life activists realized, abortion was closely connected with poverty. That is even more true today than it was in the early 1970s. Fifty percent of the women seeking abortions are living below the poverty line, and another twenty-five percent have incomes that are only barely above it. A majority are already mothers of at least one child, and many of them believe that they lack the resources to care for another baby.

The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops has repeatedly noted the close correlation between poverty and abortion. Women are more likely than men to be poor, and women who are poor are more likely to have abortions. The best way to reduce the abortion rate, the deputy director of the USCCB’s Secretariat for Pro-Life Activities declared in 2013, was to “fight poverty.”

This has been the belief of many pro-life Catholics and some pro-life activists from other religious traditions for the past half century, but as a whole, the pro-life movement has not emphasized this message since the beginning of its alliance with the Republican Party more than forty years ago. As a result, the pro-life cause is now closely associated with a political ideology whose stance on social welfare policy runs directly counter to the views that were ubiquitous in the pro-life movement before Roe and that would probably go a long way toward reducing abortion rates and saving the lives of both the unborn and the born.

Several of the states that will ban abortion this summer—including Texas, Mississippi, and Alabama—have refused a federal Medicaid expansion that would extend healthcare coverage to low-income people whose household income is no more than thirty-eight percent above the poverty line. Louisiana, another one of the thirteen states with a "trigger ban" to prohibit abortion after the reversal of Roe v. Wade, has the highest maternal mortality rate in the country, with a death rate for Black women that is four times as high as for whites. A comprehensive pro-life strategy that sees poverty and healthcare as matters of justice—as they were for many pro-life activists immediately before Roe—would address these issues as part of its defense of human life and would not merely settle for a round of new abortion restrictions.

The end of Roe presents an opportunity for those who believe in the value of all human life to live up to the historic values of their movement, with the full realization that the future credibility of their movement will depend on it. In response to Dobbs, the pro-life cause is less popular than ever in liberal states that are poised to expand abortion rights. To regain credibility in these regions, pro-lifers will have to demonstrate that they care about more than merely banning abortion, and that they are seeking the preservation and flourishing of all human life—including the lives of mothers who are struggling to access affordable healthcare or who do not know how they will find the resources to care for their children. And in conservative states that are implementing abortion bans this summer, pro-lifers will have to find a way to make sure that women who become pregnant while in poverty will not fall further below the poverty line as a result of their choice to bring new life into the world. Pro-lifers will also need to find a way to help women who are thinking about using the abortion pill or traveling across state lines to access an abortion elsewhere will be given the financial and social assistance they need to give birth and care for their children.

Some of this assistance can be provided through private charities, but as Charles Camosy has argued, reducing the abortion rate will also depend on structural social changes, such as improved family leave policies. This, in fact, is in keeping with the vision of many pro-life activists of the early 1970s who did not merely want to influence individual decisions about abortion but instead create a new national culture of life.

We have never had a national culture of life, which means that achieving it is not merely a matter of turning the clock back to 1972 and returning abortion policy to the states. Some pro-life activists hope that Dobbs will eventually lead the way to a national ban on abortion, but in today’s polarized political climate, that is unimaginable—and even if it could happen, it would not address other related issues of human life, such as the death rate for pregnant women in parts of the Deep South. Instead, we are likely to live for some time with a patchwork of widely varying state policies on abortion, with some states banning the procedure but providing minimal healthcare resources for pregnant women, and other states providing expanded healthcare but also funding abortions.

A pro-life campaign that maintains the priorities of the pre-Roe version of the cause will challenge the assumptions behind each of these policies, and will seek to create a culture of life not only in abortion law but also in all areas of public policy that influence women’s abortion decisions. The creation of a just, equitable society in which poverty is reduced and women are empowered might be the best thing that pro-lifers can do right now to reduce the number of abortions. That was the case before Roe. And it might be the case now.