In the climactic chapters of John’s Gospel, Jesus shows himself alive to the eleven apostles (20:19-23), invites doubting Thomas to probe the scars in his hands and side (John 20:24-29), and eats bread and fish with the disciples on the shores of the Sea of Tiberias (John 21:1-14). Christians have historically understood such passages to affirm that Jesus is risen to life in his crucified body. However, David Bentley Hart, in a recent article in this journal (“The Spiritual Was More Substantial than the Material for the Ancients”), argues for a very different reading. For Hart finds in 1 Corinthians 15, and throughout much of the rest of the New Testament, a conception of resurrection—both of Christ and of the faithful—involving the replacement of the corruptible body of flesh with a new “spiritual” or “celestial” body composed of the imperishable substance of spirit (the nature possessed by angels and spirit beings). According to Hart, when Paul, John, and other New Testament authors speak of Jesus or the faithful being “raised” to life, this involves “the transformation of the psychical composite into the spiritual simplex—the metamorphosis of the mortal fleshly body that belongs to soul into the immortal fleshless body that belongs to spirit.” It was, Hart claims, in such a “spiritual” body, “purged of every element of flesh and blood and (perhaps) soul,” that Christ rose.

How can one square such a conception of resurrection with John’s reports of Jesus eating with his disciples and inviting them to touch his hands and side? Hart argues there is no inconsistency. He readily admits that “no other gospel places greater emphasis upon the physical substantiality of the body of the risen Christ” but maintains that even this is perfectly compatible with his claim that Jesus arose in a body composed of spirit rather than of flesh. The key, Hart asserts, is to grasp “the ancient view of things”—a worldview foreign to moderns but shared by all the New Testament authors—according to which “spirit” (Greek: πνεῦμα) was not immaterial or incorporeal, but a substantial, material, physical entity. The disciples can touch the risen Christ, Hart argues, not because he any longer has flesh, blood, or soul, but because the “spiritual simplex” of which he is composed is also a material reality. Out of touch with such a world of thought, modern Christians mistakenly assume that such physical encounters of Jesus with the disciples must mean that he has risen from the tomb in his body of flesh and bones. Ancient readers, by contrast, would have immediately understood (or so Hart contends) that it was not in his crucified body, but as a “wholly spiritual being” that Christ encountered the disciples, having once for all shed the corruptible and irredeemable flesh.

As all of Hart’s work, the essay in question is written with wit and verve. Hart is a brilliant polymath who is always worth reading. Nonetheless, the thesis of Hart’s article, which concerns a core belief of the Christian faith, is not sustainable. Moreover, the historical claims regarding the ancient world on which he founds this thesis are misleading. Hart’s essay thus calls for a sympathetic but critical response.

The first point I wish to discuss is the ramifications of Hart’s thesis for Christian faith. Hart maintains that his understanding of the risen body of Christ as a body composed of spirit, purged of flesh and blood, contradicts “not so much Christian dogmas as indurated habits of thought and imagination.” A reading that affirms the reality of the fleshly embodiment of the risen Lord is, Hart insists, the result of a peculiarly “Protestant picture of the pagan and Jewish worlds of late antiquity,” entirely out of touch with “the age of the early church.”

Such a claim is in strong need of correction. Contrary to Hart, it is the insistent and consistent teaching of the ancient Church, and of her classical theologians such as Justin, Irenaeus, Tertullian, Jerome, Augustine, and John of Damascus, that Jesus rose from the dead and ascended into heaven with the same body of flesh and bones in which he was crucified, his body now glorified and made incorruptible. I will cite only a very few representative passages (although, as every student of the ancient Church knows (I could cite hundreds more):

- For I know and believe that he was also in the flesh after the resurrection. And when he came to those with Peter, he said to them, “Take, touch me and see that I am not a bodiless spirit.” And immediately they touched him and believed, mingling with his flesh and his blood (Ignatius, Epistle to the Smyrneans 3.1-2).

- Christ arose in the substance of flesh, and showed to the disciples the marks of the nails and the opening in his side. These were the proofs of his flesh, which rose from the dead. In the same way, says the apostle, “he will raise us up through his power.” (Irenaeus, Against Heresies 5.7.1).

- The Lord said “Touch me and see, because a spirit does not have flesh and bones as you see that I have” [Lk 24:39], and he said to Thomas, “Reach your finger here, and behold my hands, and reach your hand here, and put it into my side; and don’t be unbelieving, but believe” [John 20:27]. So we, too, after the resurrection will have the same members that we now use, the same flesh and blood and bones. For in holy Scripture it is the works of these, not their nature, that is condemned (Jerome, Against John of Jerusalem 28).

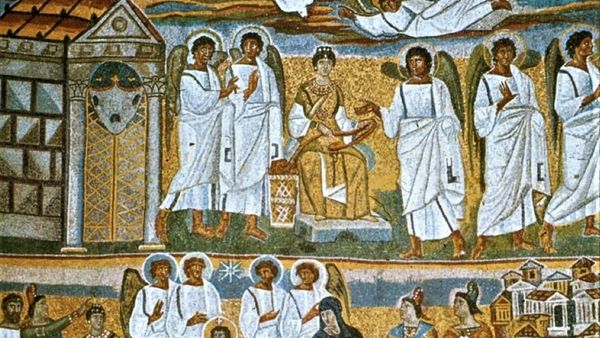

- We understand the right hand of the Father to be the glory and honor of the Deity, in which the Son of God, who existed as God before all ages and is of one essence with the Father, and in the fullness of time became flesh, is seated with his human body, his flesh sharing in the glory. For as one Person, together with his flesh, he is worshipped with one adoration by all creation (John of Damascus, On the Orthodox Faith 4.2).

- Certainly the resurrection of Christ, and his ascension into heaven with the flesh in which he rose, is now proclaimed and believed in the whole world (Augustine, City of God 22.5).

These Fathers also explicitly reject as heretical an interpretation of resurrection in the New Testament that excludes the body of flesh and blood from participation in eternal salvation. And they one and all insist that this is not an insignificant question of doctrine, but essential to the Christian deposit of faith:

- And there are some who say that even Jesus himself was [after the resurrection] in a spiritual body only, no longer in the flesh, but provided only the appearance of the flesh to the disciples. By this teaching they seek to defraud our flesh of the promise of salvation (Justin, On the Resurrection 2).

- The very concept of a “resurrection” without flesh and bones, without blood and members, is a contradiction in terms (Jerome, Against John of Jerusalem 31).

- At the resurrection the soul will not resume a celestial or ethereal body, or the body of some other creature, as certain people falsely invent. No, it will resume a human body composed of flesh and bones, and furnished with the same members of which it now consists (Aquinas, Compendium of Theology 153).

The crucial character of this aspect of the Christian gospel is evident from its important place in the Church’s historic creeds and liturgy. In the Apostles’ Creed, Christians confess their belief in “the resurrection of the flesh” (carnis resurrectionem). On Thomas Sunday, Orthodox Christians sing: “Verily, Christ called unto Thomas, saying, ‘Probe as thou wilt, thrust in thy hand and know me, that I have earthly flesh, bones, and body. Do not be doubtful, but believe.’” And Jesus’s resurrection in the flesh is, of course, fundamental to the belief of both Catholic and Orthodox Christians that the body and blood of the risen and ascended Christ is truly present in the Eucharist.

In short, Hart’s interpretation of the resurrection narratives of the Gospels is not, as he contends, without import for “Christian dogmas,” simply a healthy corrective of a mistaken “Protestant picture.” It is an interpretation that is not consistent with the historic teaching of the Church, East and West.

But what of Hart’s claim that this thesis of a Christ risen not in the flesh but “in an angelic or spiritual condition” is entirely consistent with the physical palpability of Jesus’s body in the resurrection narratives of the Gospels, because all ancient persons (including the New Testament authors) regarded “spirit” as a material, tangible substance? Although he goes too far in attributing this view to “all the ancients” (for there were a variety of views on the subject), Hart is certainly correct that many ancient philosophers understood “spirit” as a corporeal or material substance (a viewpoint especially associated with the Stoics). However, the critical point Hart fails to grasp is the kind of corporeal substance they believed “spirit” to be.

This is the background against which any ancient person would have read the descriptions of the resurrected body of Jesus in the Gospels (whatever their views about the corporeality or incorporeality of “spirit”). For all were in agreement that spirit (πνεῦμα; Latin, spiritus), in contrast with the coarse, dense, tangible human body, is as a fine air or breath, incapable of being touched or handled, entirely intangible and impalpable (see: Seneca, On Mercy 1.3.5; Epistles 50.6; Sextus Empiricus, Against the Mathematicians 7.375; Stoicorum Veterum Fragmenta 2.439-440; Cicero, On the Nature of the Gods 2.116-117). So in the Jewish context, it was a given that angels or spirits cannot be touched or grasped, and cannot eat or drink (Tobit 12:19).

That is why the resurrection narratives in the Gospels are so powerful. Everyone in the ancient context would have immediately understood that the Jesus so described could not have a body composed of spirit. For, they knew, a spirit was incapable of being handled or touched, or of bodily acts such as eating and drinking. Any ancient reader would have grasped what kind of body this is: the same earthly, fleshly body in which Jesus was crucified, but now glorified and transformed to be imperishable. "Touch me and see, because a spirit (πνεῦμα) does not have flesh and bones as you see that I have" (Luke 24:39).

Much of Hart’s essay is devoted to an analysis of 1 Corinthians 15, Paul’s great “resurrection chapter.” Hart dismisses the conclusion of New Testament scholar N.T. Wright that this passage is consistent with the doctrine of the resurrection of the flesh. Instead, Hart maintains, Paul in this chapter envisions an ethereal resurrection body of celestial substance rather than of flesh. Hart finds proof of this in Paul’s reference to the risen body as a “spiritual body” in 1 Corinthians 15:44. Hart imagines that this constitutes firm evidence that Paul “thought of ‘spirit’ as being itself the substance that will compose the risen body.”

Let us examine Hart’s translation and interpretation of this crucial verse. In 1 Corinthians 15:44, the “spiritual body” is the second element of a contrasting pair, the σῶμα ψυχικόν and the σῶμα πνευματικόν, terms which Hart translates respectively “psychical body” and “spiritual body.” Hart’s translation of σῶμα ψυχικόν as “psychical body” reflects that fact that ψυχικός is an adjective related to the Greek word “soul” (ψυχή or psyche). Likewise, Hart’s translation of σῶμα πνευματικόν reflects the fact that πνευματικός is an adjective related to the Greek word “spirit” (πνεῦμα or pneuma). Hart’s translation is unique, perhaps a bit strange to the ears—but remarkably precise. It is certainly the best translation into English of Paul’s contrasting terms that I have seen. For Hart’s rendering brings out clearly, what other English translations more or less obscure, that Paul in this verse contrasts, not flesh and spirit, nor body and soul, nor materiality and immateriality, but soul and spirit.

What is the point of Paul’s contrast? Hart’s answer is founded upon another key claim regarding ancient thought. Hart asserts that in the ancient view of things “soul” (ψυχή; Latin, animus or anima) was “the life-principle proper to the realm of generation and decay,” confined to the earth and inherently mortal and corruptible. By contrast, “spirit” (πνεῦμα; Latin, spiritus) was an ethereal or celestial substance, “the element that was imperishable by nature,” having its origins in the heavens and thus “not confined to any single cosmic sphere.” This “central opposition between the two distinct principles of soul and spirit,” Hart asserts, was a core assumption of all the ancients, including Paul and the other authors of the New Testament. Reading 1 Corinthians 15:44 in this light, Hart understands Paul to contrast the “coarse corruptible body compounded of earthly soul and material flesh” with a risen body composed of celestial spirit, which has shed “every element of flesh and blood and (perhaps) soul.”

However, Hart’s interpretation of 1 Corinthians 15:44 is mistaken, for the assumptions regarding ancient thought on which his interpretation is based are wrong, and (one must say) egregiously so. First, in utter contrast to Hart’s portrayal, ancient pagan thinkers did not regard ψυχή or “soul” as the life-principle of earthly decay, but as divine and heavenly in its origins. Platonists believed that, unlike the perishable body, the soul (ψυχή or animus) was eternal, immortal, and imperishable (see Plato, Timaeus 41d-43a; Phaedo 80-107; Phaedrus 245; cf. Cicero, Tusculan Disputations 1.53-71). Similarly in Cicero’s famed account of the “Dream of Scipio” in his book 6 of the Republic, Scipio learns that the origin of the human soul is among the stars (“human beings have been given their soul from those eternal fires, which you call stars and planets,” 6.15). Likewise for the Stoics, the soul has its origins and true home in the celestial regions (Seneca, To Helvia 6.7-8; Epistles 102.21-28; To Marcia 24.5-26.7).

Second, Graeco-Roman thinkers did not use “spirit” (pneuma) in contrast with “soul” (psyche), as Hart claims. Platonists and Peripatetics used pneuma (Latin: spiritus) straightforwardly of the “breath” and “air” exhaled by the lungs. The Stoics used the word in this way as well, but they also used it of the divine spirit or pneuma that they believed pervades the universe and subsists as the soul (psyche) within each person. The Stoics therefore regularly used “soul” and “spirit” synonymously (Diogenes Laertius 7.156-157; Stoicorum Veterum Fragmenta 1.135-140). A similar synonymous usage is common in Jewish and early Christian texts with reference to the “soul” or “spirit” of individual persons. Unlike the Platonists and Stoics, they did not think of the human soul or spirit as divine, or having its origin from the stars, but as created by God. But in this different context they also regularly use the terms “soul” and “spirit” synonymously. A good example is Luke 1:46-47: “my soul (ψυχή) magnifies the Lord, and my spirit (πνεῦμα) rejoices in God my savior” (see also LXX Daniel 3:39; LXX Job 12:10; Wisdom of Solomon 15:11; Josephus, Antiquities 11.240; Philo, That the Worse Attacks the Better 84). Other ancient Jewish and Christian texts relate the human soul and human spirit closely, either leaving their precise relation unstated (1 Thess 5:23; Heb 4:12; LXX Daniel 3:86), or understanding the spirit as the essence of the soul (Philo, Who is the Heir? 55; Justin, Dialogue with Trypho 6.2; On the Resurrection 10). So then, we see that ancient pagan authors never use ψυχή and πνεῦμα in contrast in the way Hart suggests, and often use them more or less synonymously, and that this synonymous usage is also common in ancient Jewish and Christian literature.

However, in certain distinctive passages within ancient Jewish and early Christian writings, ψυχή and πνεῦμα (or their related adjectives) are set in contrast. This is, as we have seen, something that never occurs in pagan literature, and is contrary to the usual collocation of “soul” and “spirit” in Jewish and Christian texts. This contrasting usage in certain passages within these texts is therefore a striking fact that calls for an explanation. The explanation is that these passages do not speak of the human soul and spirit, but contrast the human soul with the divine Spirit of God (1 Cor 2:14-15; Jude 19; Philo, Spec, 4.49; Virt. 217). And it is this usage that provides the key to Paul’s meaning in 1 Corinthians 15:44, where he contrasts the present “psychical body” (“psychical” = ψυχικός, related to ψυχή or “soul”) and the risen “spiritual body” (“spiritual” = πνευματικός, related to πνεῦμα or “spirit”). Paul had already introduced this pair of adjectives in chapter two of the same letter, where he contrasted “the psychical (ψυχικός) person, who does not welcome the things of the Spirit of God” (2:14) with “the spiritual (πνευματικός) person” (2:15), inhabited and illumined by the Holy Spirit (2:16; 3:16-17; 6:11; 6:19). In chapter two of 1 Corinthians, Paul’s opposition between the “psychical” and “spiritual” person is the contrast between the person untouched by the Spirit and power of God, and the person transformed by the presence and indwelling of the Holy Spirit.

Jude likewise defines the “psychical” (ψυχικός) person as “not having the Spirit” (Jude 19). When, then, Paul uses these same terms in 1 Corinthians 15:44 regarding the body, it is clear that Paul’s contrast is between the present body animated only by the soul, and therefore mortal and corruptible, and the risen body which will also be energized by and infused with the Holy Spirit, and thus transformed to be glorious and imperishable. This is, in fact, the precise way in which the ancient interpreters of the Church read this passage:

- [Expounding 1 Corinthians 15:44:] The psychical [animalis] bodies [to which the apostle refers] are those which partake of the life of the soul [anima]. When they lose this life, they perish. Then, rising through the power of the Holy Spirit, they are made spiritual bodies, that is, having a permanent and everlasting life through the Spirit [Spiritus] (Irenaeus, Against Heresies 5.7.2).

- [Again explaining 1 Corinthians 15:44:] The body, which because it is born with a soul and lives by means of the soul [anima], is fittingly called “psychical” [animalis] by the apostle, will become what he calls “spiritual” [spiritualis], because through the Spirit [Spiritus] it will rise to eternal life (Tertullian, Against Marcion 5.10).

In sum, an analysis of Paul’s language in 1 Corinthians 15 within its authentic ancient context reveals that Paul proclaimed a bodily resurrection in continuity with the Easter faith evident in the resurrection narratives of the Gospels.

Finally, the reader may wonder: why is Paul so adamant that “this mortal body must be clothed with immortality, and this perishable body must be clothed with imperishability” (1 Cor 15:53-54)? Why do the Gospel narratives so strongly stress the flesh-and-bones nature of Jesus’ risen body? Why has the Church, in her theological writings, creeds, and worship, so emphatically insisted on the resurrection of the flesh? Why would Irenaeus even assert that those who deny the salvation of the flesh “despise the entire economy of God” (Against Heresies 5.2.2.)?

Simply put, apart from the resurrection of Jesus’s crucified body from the dead, there is no good news. If the hope of resurrection in the New Testament involves nothing more than entry into a “spiritual existence” apart from the earthly body, as Hart claims, then the apostolic gospel offered merely one more expectation of spiritual afterlife among many in the ancient pagan world. On Hart’s view that Jesus rose as a disincarnate “spiritual being,” the Incarnation was only a temporary episode.

As for Jesus’s human body, born of the Virgin Mary, the power of Rome had the last word about that. Such a narrative, as Hart freely admits, “involves no particular affirmation of the goodness of fleshly life.” Indeed, Hart claims that in the thought-world of the New Testament “flesh is essentially a bad condition to be in,” belonging inescapably to “the realm of mutability and mortality,” and so the goal of salvation can only be to “shed the flesh.” This is not redemption, but Simone Weil’s de-creation.

On this reading of the Scriptures, the original creation of human beings as embodied creatures of flesh and blood can hardly be “very good,” as we read in Genesis, but is instead tragically flawed in its original design, as the Gnostics claimed. Within a narrative in which Jesus has shed his “flesh and blood and (perhaps) soul,” the Church’s conviction that in the Eucharist she partakes of the very “body, blood, soul, and divinity” of her Lord can have no place.

“But now Christ is risen from the dead, the first fruits of those who sleep” (1 Cor 15:20). To an ancient world for which death was the everlasting sorrow, unconquerable even by the gods, the resurrection of Jesus’s crucified body from the tomb brought the good news of the true God’s victory over death. Moreover, the same body that was cruelly tortured and murdered by the rulers and authorities of this world is now enthroned at the right hand of God in universal power and dominion, and the one who possesses that body is coming again in glory to judge the living and the dead. “In the Incarnation creation is fulfilled by God’s including himself in it” (Kierkegaard). Jesus’s resurrection did not end the story of the Incarnation, as Hart contends.

Instead, Jesus’s bodily resurrection and ascension continued the story of the Incarnation. For in the resurrection, Jesus’s body, born of Mary, was not shed, but glorified (Rom 6:4; 2 Cor 3:18; Phil 3:21). And Jesus’s second coming, in the same body in which he was crucified and rose again, will complete the narrative of the Incarnation, and so fulfill the story of creation. For the full outworking of Jesus’s resurrection, Paul affirms, will bring about the glorification of the whole created order (Rom 8:21). And this is the context in which the Church’s celebration of her central Mystery has its home: the communion of the faithful with the body and blood of Christ as “the medicine of immortality,” assuring their own bodily resurrection to everlasting life on the last day. “The goal of the work of the Spirit is the salvation of the flesh” (Irenaeus, Against Heresies 5.12.4).