A colleague (not from the Theology Department!) once asked me who was my favorite saint.[1] When I responded “St. Joseph,” he seemed genuinely taken aback and exclaimed, “But we don't know anything about him! How can he be anyone's favorite saint?” There was a lot implied in my colleague's astonished response, and fair enough, since, considered from the point of view of bare facts about St. Joseph's life, we do not have much to go on (granting, for the moment, that there can be such a thing as “bare facts” about anyone's life). But how many such “facts” does one really need in order to find a person, even on the horizontal plane of this life on earth, so attractive that one wants to befriend him or her?

The dimensions of personal attractiveness are not easily reduced to bare facts about one's life. Perhaps, too, a mutual friend or a trusted advisor has introduced you, providing a few essential indications of character as the basis for a possible friendship. In such a scenario, the trustworthiness of the friend or advisor introducing you is part of the appeal of the prospective friend. Even more, the perspective of the mutual friend or trusted advisor is already a factor in the potential friendship and may continue as an important part of the friendship as it develops.

In the case of St. Joseph, the trustworthy friend in the analogy is the Church, and the introduction provided is the set of memories of St. Joseph preserved in scripture. These memories belong to the Church as a kind of personal subject. The Church is, in a way, a collective person—that is, the People of God, whom Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI calls a “collective subject,” in fact “the living subject of Scripture.”[2] He elaborates that “the Scripture emerged from within the heart of a living subject—the pilgrim People of God—and lives within this same subject.”[3]

The individual authors of the biblical books form part of this collective subject, who is, he continues, “the deeper ‘author’ of the Scriptures” on the human level.[4] He goes on to emphasize that “because the personal recollection that provides the foundation of the Gospel is purified and deepened by being inserted into the memory of the Church, it does indeed transcend the banal recollection of facts.”[5] It is, of course, important to remember that the memory of the Church, insofar as the memories contained are scriptural, is inspired. Benedict puts it this way: “This people does not exist alone; rather it knows that it is led, and spoken to, by God himself, who—through human beings and their humanity—is at the deepest level the one speaking.”[6]

Scriptural memories are, as it were, definitive memories in the overall remembering of the Church that comprises apostolic tradition. The main content of this memory is, of course, the mystery of Christ, the Word made flesh, as Dei Verbum, the Second Vatican Council's Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation, articulates. Jesus “completed and perfected revelation,” and, according to the dogmatic constitution:

Everything to do with his presence and his manifestation of himself was involved in achieving this: his words and works, signs and miracles, but above all his death and glorious resurrection from the dead, and finally his sending of the Spirit of truth” (DV §4).

Everything in Christ's life, in other words, participates in the mystery of his person that sums up revelation. As the Catechism of the Catholic Church puts it, “Christ's whole life is mystery . . . From the swaddling clothes of his birth to the vinegar of his Passion and the shroud of his Resurrection, everything in Jesus' life was a sign of his mystery” (§514-15).

It goes without saying that St. Joseph is very much implicated in such a statement. To acquire a friendship with St. Joseph means, therefore, if it is authentic, a deeper acquaintance with the mystery of the Lord, and the more intimate the friendship, the deeper the appreciation of the mystery of the Incarnation. The reverse is also true. The more one has accepted the invitation of revelation to become friends with the Lord Jesus and through him the Father, the greater possibility there is for an intimate and living friendship with St. Joseph in Christ. For the whole of St. Joseph's life and identity is saturated with the mystery of Christ, and the mystery of St. Joseph in the memory of the Church is constituted wholly by its reference to the all encompassing mystery of Christ that it reflects.

Why don't we take the recommendation of our trusted advisor the Church and strike up a friendship with St. Joseph? Though it is spare enough in detail, what is authoritatively remembered under the guidance of the Holy Spirit is overwhelmingly sufficient as the basis for an intimate and satisfying friendship. We can begin with the two infancy narratives of St. Matthew and St. Luke. They are notoriously different from each other to the point of potential, if not actual, conflict. I regard the difference between the two narratives, as uncomfortable as it can feel for those who would like an easy reconciliation between them, as providential, for it shows that these two narratives are independent traditions, and yet—astonishingly—they agree on the most essential points.

Included among these are some of the most unlikely points, namely, that Mary and Joseph were husband and wife, but that before they began to live together as husband and wife, during their betrothal, an angel announced (in one narrative to Joseph, in the other, to Mary) the conception of Jesus, which, in addition, was said to have taken place through the Holy Spirit, without intercourse between Mary and Joseph or indeed between Mary and any other man.[7] It is interesting, at least, that the Gospel of Mark does not identify Jesus as the Son of anyone but God, except when it says, simply, that he is “the carpenter, the son of Mary.” These points of agreement are anything but “bare facts,” though they are indeed claims of historical truth. Such matters as the virginal conception of Jesus or the appearance of angels in dreams or otherwise cannot even in principle be historically verified, and yet the independence of the two inspired traditions does verify that these memories are as ancient as any there are about Jesus and are not simply the fabrications of the evangelists.

They are as likely (or as unlikely, I suppose you could say) as the truth of the Word made flesh, as the truth of the Incarnation itself, for they are the essential elements of the location of the Incarnation in place and time. The Incarnation is thus distinguished from myth, for it is located in place and time, and yet it is not reduced to mere history (if there is any such thing), for it was initiated outside of history and its significance transcends history. Between “myth” and “history” we find “mystery.”[8] And for all the special significance of our developing friendship with St. Joseph, all friendships are located in an analogous domain of mystery, for the interior essence of someone's truly historically located love is never simply reducible to its location in history, nor does that make an account of it a myth.

The Gospels do not tell us much about what Joseph thought about all of this. They do not give us an account of what today we might call Joseph's psychology, but the Gospel of Matthew does evoke an image of a man with a rich interior life, intent on doing God's will, always on the lookout for indications of his will, and ready to obey. Matthew recounts that Joseph was disturbed by the discovery that Mary was pregnant, and considered divorcing her, though we are not told whether this was because he thought she must have been unfaithful, or that he was already aware that some mystery larger than human devising had entered Mary's life, in which he was not sure of his further place.[9] Matthew tells us that as a “righteous” or “just” man he decided to divorce her, following the Law, the best indication of God's will that he knew, yet “quietly,” yielding the benefit of the doubt in so doing to Mary or to God or both, as the Protevangelium of James seems to suggest. In obeying the Law “quietly,” Joseph is obeying both its letter and its spirit, divorcing Mary not as a public vindication of his own person, but as a refusal to claim that he knows God's intentions fully and as an openness to what they might be. In this, the evangelist is saying, does his righteousness—or, we could translate, sanctity—essentially consist. We can see that this is true to Matthew's intentions, for when the angel reassures Joseph in a dream that he should take Mary into his home, he does so without any hesitation.

The Gospel of Luke, for its part, does not register even a protest, worry, or anxiety on behalf of Joseph, and we might begin to think that he is an afterthought, merely a narrative or dramatic prop, were it not that the Gospel indicates his lively involvement in his family's life as husband and father up to and past Jesus's twelfth year. This sustained involvement is described in more detail than that of any other father in the Gospel of Luke—the father of Jairus being perhaps a suggestive second (cf. Luke 8:40-56) and not counting the fathers who are characters in parables. Luke privileges the reflective “pondering” of Mary, instead of Joseph's, and provides explicit memories of the thoughts and sayings that proceed from her pondering and return us to it.

But Luke is careful to point out that the angel's Annunciation is to Mary, a virgin who was betrothed, and betrothed explicitly to Joseph. Thus, while Joseph is not consulted, neither is he just an also-ran who happens along at some random point in time. It is not Mary alone, but Mary precisely as betrothed who is addressed, and so her marriage to Joseph is part of the divine plan for the Incarnation and not incidental.

In this matter, the Gospels of Matthew and Luke agree, though they bring out the point each in their own way. Neither Gospel is so indiscreet as to try to reproduce the conversations between Mary and Joseph about their marriage and their vocation, though they must have discerned it together, in some manner unique to themselves. The Gospels' reticence on this point, in a way, verifies that this domain is truly spousal, truly intimate, and not for public view. Jesus enters this world embraced in an intimacy which, if not physical, is nevertheless truly spousal. It is important that we know that both Mary and Joseph are not simply passive instruments of God's will, and each evangelist implies this for one of them and verifies it for the other. God's will is accomplished in their free acceptance of it and in the bond of marital intimacy that is sealed in shared obedience to God's will.

In the case of Joseph, the two Gospel accounts converge in portraying him as having no “terms” for his involvement as husband and father, except for the terms that God offers, and they seem paltry enough. He is promised no “seed,” as Abraham was, nor, more poignantly—since he is in the line of David—as David was. And though Mary is his betrothed, in neither account is Joseph even consulted about her pregnancy. Yet once he is sure it is God's will, he takes his place as her intended husband. He understands she does not thereby become his property; nor, for that matter, does he regard himself as his own private property.

He becomes a husband and a father in dialogue with God's Law in its fullest dimension. He is depicted as someone whose exercise of husbandhood and fatherhood, and therefore of manhood (since these offices are exclusively those of a man) yield him no claims that he cares to exact on his own behalf. He rather exercises these offices of his manhood as instances of complete openness to God's will, without fanfare or display. And yet he is no less a man, and in fact one could argue that he is the Bible's most explicit revelation of what it means to be a man, for St. Joseph's identity is completely coincident with his roles as husband and father, without remainder.

We are not informed by the Gospels as to whether Joseph's “terms” had included an expectation of sexual intercourse with Mary at some point, or indeed what Mary thought about it, though we are given some clues. Matthew, furthermore, goes to the trouble of making it explicit that Joseph did not engage in sex with Mary before or during Mary's pregnancy, even though by that time it would probably not have been forbidden.[10] The Gospels do not mention anything explicit beyond this statement, but they do make it clear that the sex life of Mary and Joseph was something intimately relative to the mystery of the overarching designs of God in the birth of Jesus, and that Mary and Joseph both came to understand that this would involve a unique degree of renunciation or bypassing of married sex.[11] The Gospels allow them to continue their discernment unobserved by the reader, as part and parcel of pondering the dimensions of the awesome mystery of which their marriage is a part and thus of the uniqueness of their marriage.

The Gospels ask of us, the Church, the same attitude of openness toward the uniqueness of this marriage. The clues provided justify the ancient discernment of the Church that these spouses never had sex, and that this renunciation was part of the trueness of their true but unique marriage, rather than militating against it. The Protevangelium of James (usually dated to around 150AD) testifies to the antiquity of belief in the perpetual virginity of Mary, and, contrary to the insults often heaped upon the text, not only proclaims the doctrine, but cautions against an overly hasty assumption about what it might mean. The birth of Jesus takes place in the midst of an obscuring heavenly light, so that its exact character cannot be ascertained.[12] Salome puts her hand to the flesh of Mary to see if her hymen is intact, a gesture reminiscent of that of Doubting Thomas in the Gospel of John (John 20:24-29) and so indicating that the doctrine is in some sense tied to the mystery of the new creation in Christ.[13]

She does discover that Mary's hymen is intact, and yet as a result her hand withers, though it is immediately healed. She is not judged overly harshly, but just harshly enough to allow the reader to see that though it is true. The reader should be warned against assuming he or she has or could fully grasp the mystery of the childbearing of the Virgin, a physical truth yet, like the resurrection itself, is not fully reducible or even fully specifiable in its physical dimensions. Karl Rahner's warning to his readers some 1,800 years later—that “there are physical events which, however naturally they may appear to be the direct consequences of the constitution of man, yet must be recognized by the more penetrating and comprehensive eye of faith”—is fully congruent with this text.[14]

Famously, the Protevangelium of James also depicts St. Joseph as an elderly widower, fully conscious of how ridiculous it will look for him to seem to be in the position of Mary's husband.[15] It will look as though he was so lustful that he, though he already had a long life and family, could not resist the attraction of a new, young wife. This is the writer's solution to the seeming counterevidence to the perpetual virginity of Mary—namely, the mention of “brothers” of Jesus in the Gospels. In this text, Joseph, afraid of disobeying God, receives Mary and puts up with looking foolish, and this solution has persisted in the Eastern Church and iconography. Without commenting on his age, Origen accepts as settled doctrine the perpetual virginity of Mary and consequently that Joseph's sons by an earlier marriage are the “brothers” of Jesus.[16]

In modern times, this theory has (with modifications) been accepted by writers as diverse as Elizabeth Johnson and Gerald J. Kleba,[17] who depict Joseph as a widower with children but a young one, in his late twenties or thirties, thus bypassing the later objection of St. Jerome, who insisted that Joseph could not credibly pass as Mary's husband if elderly and suggested he was a virgin. This suggestion, accepted by St. Augustine, came to be the dominant position in the West.[18] It is especially beautifully treated in Pope St. John Paul Il's evocation of the mystery of St. Joseph in the apostolic exhortation Redemptoris Custos, for there he explains how Joseph's own voluntary renunciation of marital relations makes him no less a true human father to the Lord Jesus:

In this mystery of the Incarnation, one finds a true fatherhood: the human form of the family of the Son of God, a true human family, formed by the divine mystery. In this family, Joseph is the father: his fatherhood is not one that derives from begetting offspring; but neither is it an “apparent” or merely “substitute” fatherhood. Rather it is one that fully shares in authentic human fatherhood and the mission of a father in the family. This is a consequence of the hypostatic union: humanity taken up into the unity of the Divine Person of the Word-Son, Jesus Christ . . . Within this context, Joseph's human fatherhood was also “taken up” in the mystery of Christ's Incarnation (§21).

Contemporary iconography that depicts St. Joseph as a young man thus has Jerome to thank for it. For Jerome's case to work, however, the word for “brothers” in Greek [adelphoi] must be taken to be flexible enough to refer to more distant relations, or to reflect a Semitic idiom that was that flexible. This was Jerome's position. Contemporary scholarship exhibits a sharp division on the matter,[19] and it is doubtful that it can ever be conclusive one way or the other. The benefit of the doubt actually works in favor of the tradition here.[20]

We have seen how the Protevangelium of James receives the mystery of St. Joseph in the memory of the Church. Now I would like to turn to the next-earliest contributor, Origen. While it is true that the major flowering of devotional and theological literature about St. Joseph does not really take place until the fourteenth century, and that it was the public gratitude of St. Teresa of Avila to him that caused it to grow even more richly, the ancient Church is not without depth of reflection on St. Joseph. In my view, with regard to patristic commentary on St. Joseph, Origen's is certainly the deepest. In his Homilies on Luke, commenting on Luke 1:26-27, Origen states:

Again I turn the matter over in my mind and ask why, when God had decided that the Savior should be born of a virgin, he chose not a girl who was not betrothed, but precisely one who was already betrothed.[21]

Origen tells us that he found the key to understanding this in a letter of Ignatius of Antioch, writing:

I found an elegant statement in the letter of a martyr—I mean Ignatius, the second bishop of Antioch after Peter. During a persecution, he fought against wild animals at Rome. He stated, “Mary's virginity escaped the notice of the ruler of this age.”[22]

In his letter to the Ephesians, Ignatius had commented that there were three secrets wrought in God's silence and kept hidden from the prince of this world, namely the virginity of Mary, her childbearing, and the death of the Lord.[23] Ignatius is taking up a Pauline theme, namely, the essential “hiddenness” of the mystery of the Incarnation, as part of a logic or wisdom that is not of this world. Origen brings out this Pauline logic:

The Apostle maintains that the opposing powers were ignorant of [the Lord's] Passion. He writes, “We speak wisdom among the perfect, but not the wisdom of this age or the wisdom of the rulers of this age. They are being destroyed. We speak God's wisdom, hidden in a mystery [in mysterio absconditam]. None of the rulers of this age knows it. If they had known it, they would never have crucified the Lord of glory.”[24]

The logic of the Incarnation is not a logic of this world, of manifest credential, rhetorical leverage, intimidating erudition, or powerful status. Origen reminds his hearers that in the temptation scenes in the Gospels, the Savior never revealed to the devil that he was the Son of God, refusing to yield to the temptation precisely of pulling rank, of reducing himself to the logic or wisdom of this world, as it were, as though his status qua status would conquer the devil. He refuses to play the devil's game but is operating according to another wisdom of which, according to Christ's will, as Origen points out, the devil was kept ignorant. This means, too, that the mystery of Christ, even when revealed fully, remains a mystery, its wisdom irreducibly hidden in mystery, resisting and rejecting the logic of this world and its prince.

At any rate, Origen locates St. Joseph and his marriage to Mary squarely within the logic of hiddenness intrinsic to the mystery of the Incarnation. There is a discreet beauty here in the Providence of God. In a way, there is nothing so hidden, both in the sense of unobservable and in the sense of unremarkable or ordinary, as the conception of a child in the intimacy of a married couple—even, initially, to the couple themselves. It is just here, in the bosom of this intimacy, that the mystery of the Incarnation was “hidden,” in the conjugal intimacy shared by a “righteous” man and a woman “full of grace.” Origen comments, first quoting Ignatius:

“Mary's virginity escaped the notice of the ruler of this age.” It escaped his notice because of Joseph, and because of their wedding. If she had not been betrothed or not had a husband, her virginity could never have been concealed from the “ruler of this age.” Immediately, a silent thought would have occurred to the devil: “How can this woman, who has not slept with a man, be pregnant? This conception must be divine. It must be something more sublime than human nature.”[25]

The devil is on the lookout for status claims, for achievements or wonders bragged about, and yet all he sees is the intimacy of a married couple, to him boringly human, low status, and ordinary. But this is not just a show. The devil is not fooled by show; in fact, he is known for pomp and for lies. The virginity is truly hidden in this intimacy, because it is not a limit or a block but the very substance of Mary and Joseph's deeply shared conjugal intimacy. It is not an ascetical purity that Mary has worked at and Joseph does not dare stain, an achievement that stands as something more sublime than human nature and aloof from real contact. The devil would notice that right away. To dwell as Origen does, for the length of this whole homily, on why the angel came to a girl who was betrothed, is to insist that the Word made flesh was conceived in a true marital intimacy of husband and wife and most safely hidden there by God.[26]

Ignatius comments that this “secret” of God, as he puts it, emerges from the great silence of God, and although he does not quote this part of the sentence, Origen sees to it that St. Joseph is the carrier, as it were, of this silence, which continues to cling to the mystery as hidden. St. Joseph has no terms and offers to no one an account of his life. He accepts a fatherhood that is not a fatherhood, becomes a father in renouncing a natural paternity, allows the designation “father” to be used of him without advertising that his is a very special case.

His silence marks the intimacy of his total self-gift and, one could say, self-immolation into a paternity he cannot brag about and an identity of which he can give no account except to and in the heart of Mary his wife. But this, in traditional piety—and not without biblical reason, if Ignatius and Origen are reading correctly—makes him not the image but the shadow of the Eternal Father whose identity is dark and unknowable because it consists in the complete effacement of identity that is the begetting of the Son (like a supra-cosmic black hole of which St. Joseph is the visible version). But what is darkness and self-effacement and blankness on the one side of self-immolation is generation and paternal love and affection on the other side, toward Jesus.

Origen does not neglect the fatherly side of St. Joseph. We can turn to that point briefly, for his remarks can help us understand the sources of devotion to St. Joseph. In Hom. Luc. 17, Origen comments on Luke 2:33, “And his father and mother were astonished by the things that were being said about him.” Origen points out that Luke had already made it crystal-clear that “Jesus was the son of a virgin, and was not conceived by human seed. But Luke has also attested that Joseph was his father.”[27] Origen then asks, “What reason [causa] was there that Luke should call him a father when he was not a father?” He goes on to comment that the simple explanation is that “the Holy Spirit honored Joseph with the name of ‘father’ because he had reared Jesus.”[28]

And Origen does not deny that explanation,[29] but continues:

One who looks for a more profound [altius] explanation can say that the Lord's genealogy extends from David to Joseph. Lest the naming of Joseph, who was not the Savior's father, should appear to be pointless, he is called the Lord's “father,” to give him his place in the genealogy.[30]

In other words, if Mary gives the Lord her flesh, Joseph, for his part, provides the Lord with his identity, his place in the line of human history, someone who is not just “flesh” but has a family identity. The significance of this inclusion, apart from verifying his status as Son of David, is more apparent if we recall an earlier passage from Hom. Luc. 11, commenting on the census at Bethlehem:

Someone might say, “Evangelist, how does this narrative help me? How does it help me to know that the first census of the entire world was made under Caesar Augustus; and that among all these people the name of ‘Joseph, with Mary who was espoused to him and pregnant,’ was included; and that, before the census was finished, Jesus was born?”[31]

Origen is pointing out that this seems to be nothing more than a bare historical fact. It seems to contain nothing spiritual. Origen answers his own question almost as if he had read the Catechism's statement that “Christ's whole life is mystery” (§514-518), at least as his life is recorded in Scripture. He continues:

To one who looks more carefully, a mystery [sacramentum] seems to be conveyed. It is significant that Christ should have been recorded in the census of the whole world. He was registered with everyone, and sanctified everyone. He was joined with the world for the census, and offers the world communion with himself. After this census, he could enroll those from the whole world “in the book of the living” with himself.[32]

It is Jesus's identity as the son of Joseph that permits him to be enrolled in a particular line of human descent, not in a way that reduces Christ to that line of descent but in a way that catches all of our lines of descent up into a descent derived from him, the most authentic genealogy of all, the book of the living. By refusing to conquer Satan by revealing his identity as Only-Begotten of the eternal Father, but by emptying that identity into hiddenness, into his identity as Joseph's son, into his place in the genealogy of Joseph, the Savior catches all of our genealogies up into the Book of Life.

In a surprising way, then, the paternity of Joseph, through Mary as her husband, and in Christ, is thus extended to us. Through his fatherhood, we are all enrolled in the Book of Life. St. Joseph is thus more than a friend. We can call him “Dad,” just as Jesus did, if we want to,[33] as the deepest way of evoking the mystery of St. Joseph in the memory of the Church. And yet when we look back on that fatherhood to try to clarify or objectify or specify it, we see, in a way, nothing.

We see an effacement rather than a claim; a hiddenness rather than assertion; silence and not speech; something easily overlooked; someone of “no particular interest.”[34] The generous obedience of St. Joseph to the vision of God is astonishing. No one asked him how he felt about his wife's being consulted, when he was not, on an intimate matter affecting their whole married life, or about raising someone else's kid and giving up his own natural paternity. But his sacrifice in generous obedience to the will of God became a home in this world for Jesus, his legal son, and for Mary, his wife, both treasures of divine initiative. They were hidden, as it were, in and by his paternal love, as though by Harry Potter's cloak of invisibility, completely concealed from the Prince of this World, to whom love is always and wholly invisible. This act submerges Joseph in the “deep silence of God” itself, as Ignatius calls it.[35] St. Paul says in Colossians 3:3, “For you have died, and your life is hid with Christ in God.” There is something intrinsically hidden about the Christian life, and we see the form of this hiddenness revealed, in advance, in St. Joseph. His life, by its very structure, cannot provide an accounting of itself without undoing itself.

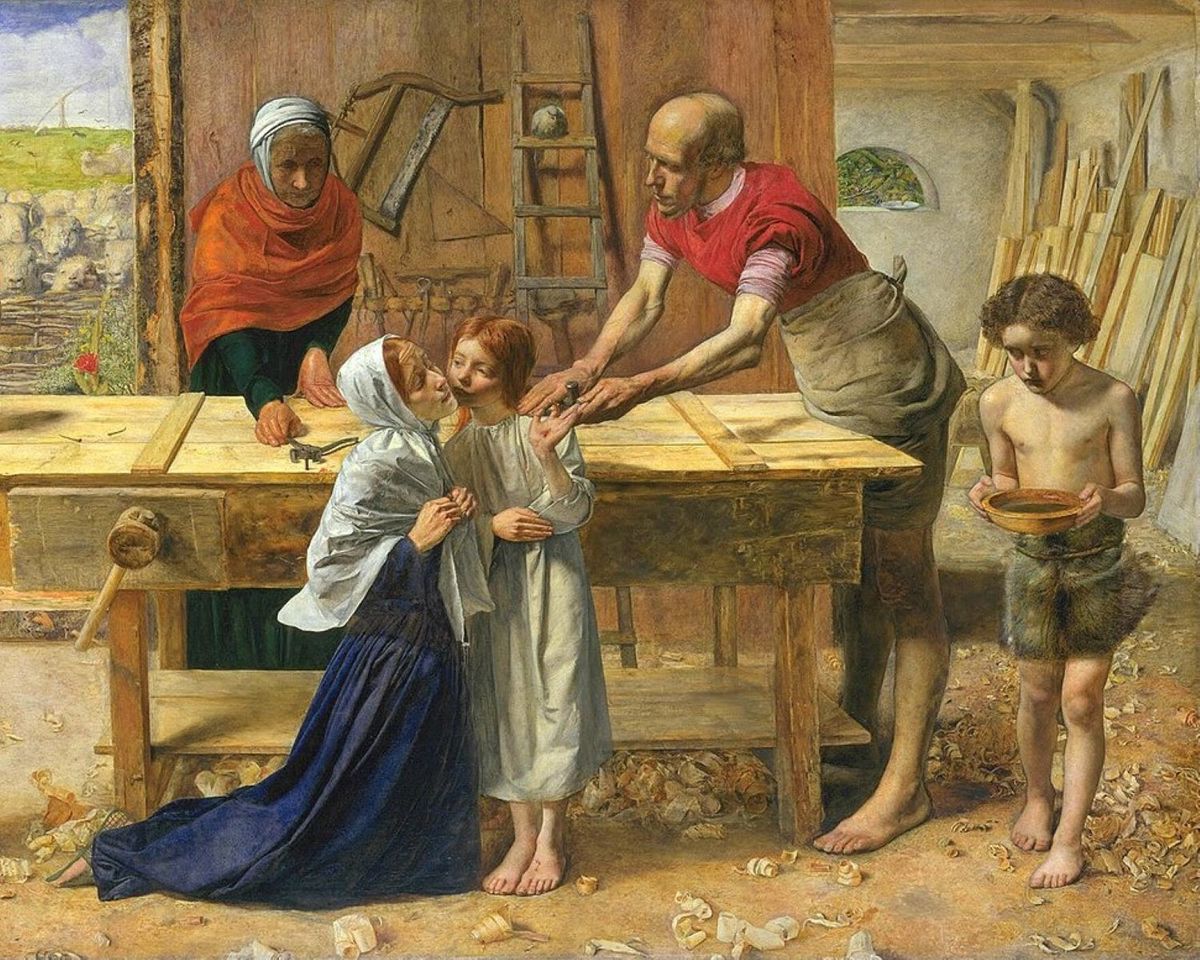

A mosaic of St. Joseph, commissioned by Pope St. John XXIII, and placed over the side altar in St. Peter's Basilica, where the Blessed Sacrament is reserved, uniquely depicts the warmth and beauty of this saint. In the mosaic, Joseph is on his back porch, hanging out at home. He is holding the child Jesus in his right arm. Jesus is not a month-old infant; rather, he looks to be about two years old. This depiction gives Joseph's figure a look of immense strength, because he manages to hold such a big, active kid on one arm with no trouble.

In his left hand he holds his identifying iconic sign, the staff blooming with the lilies of purity. He holds it a little stiffly, as though a neighbor had chanced upon him and asked him to pose for a picture with his son, insisting that Joseph hold the staff too. He is in the middle of taking care of his two-year-old, and someone has asked him to pose. But he tolerantly obliges, picks up the baby, and looks at the camera. His face is calm but hardly grave; instead, even though posing for an annoying family picture, his face seems to take it in stride and seems to radiate happiness. It is a face familiar to any dad.

Here is the hiddenness of St. Joseph, who accepts the utterly common lot of a dad holding his kid, without fanfare, though he is holding the Word Incarnate and could claim glory and fame. Jesus, for his part, pays no attention to the imaginary photographer, but rather seems wholly delighted with his dad, for what on St. Joseph's side is the continuous immolation of selfgift, is on Jesus's side the brilliant radiance, comfort, and charity of paternal love, that cloak of invisibility that gives even the Word of God a genuine childhood. This same love keeps him hidden from the Prince of Darkness until it is time for him to confront him alone, armed only with the love he had learned, in part, from his earthly dad.

If, as St. Augustine taught, true sacrifice is always a work of mercy, then St. Joseph's whole fatherhood is “rich in mercy” and is, in fact, one great work of mercy that extends all the way to us. Devotion to St. Joseph, therefore, means that as the genuine mystery of his paternity is revealed to us little by little, we grow up to accept the form of the Christian life as—in Baptism—a hidden one, a death to the noise of the world and a life in the silence of God, which is nothing other than his eternal paternal love.[36]

[1] This essay was originally presented in an earlier form as part of the "Saturdays with the Saints" lecture series hosted by the McGrath Institute for Church Life at the University of Notre Dame on September 10, 2016. I would like to thank Greg Cruess for his editorial assistance in preparing this paper for publication. Greg's marvelous work is especially evident in the notes.

[2] Benedict XVI, Jesus of Nazareth: From the Baptism in the Jordan to the Transfiguration, (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2007), xxi.

[3] Ibid., xx.

[4] Ibid., xxi.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid., xxi.

[7] See Joseph Fitzmyer, St. Joseph in Matthew 's Gospel (Philadelphia: Saint Joseph's, 1997), 9. There one finds the full list of the twelve points of coincidence between Matthew's infancy narrative and that of Luke.

[8] I have developed this theme at greater length in "A Brief Reflection on the Intellectual Tasks of the New Evangelization," Josephinum Journal of Theology 19, no. 1 (2012): 111-12.

[9] The Gospel can be read either way, as the tradition shows, even as early as the Protevangelium of James (13-14). See The Protevangelium of James, in New Testament Apocrypha, Volume I (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1963), 370-88. Nevertheless, a careful reading of the Matthean infancy narrative suggests that Joseph's decision to divorce Mary discreetly does not require the conclusion that he therefore suspected her of infidelity. Joseph is simply described as “being a just man,” an appellation intrinsically connected with the righteous figures of the Old Testament who also received the promises of God in faith. For a good explication of this non-suspicious interpretation, see Larry Toschi, Joseph in the New Testament (Santa Cruz, CA: Guardian of the Redeemer, 1991), 27-33.

[10] Although determining the precise details of betrothal and marriage practices at the time of Jesus is quite difficult, it seems likely that some amount of leniency with regard to sexual relations after betrothal but before marriage was practiced in the first century. In the Mishnah (Kethuboth 1:5) and Babylonian Talmud (Kethuboth 9b-10a, 12a), for instance, there is much discussion of the claims that a man can bring against his betrothed on the grounds of virginity precisely because such a leniency was common (see esp. 12a). As Raymond Brown notes, however, these same rabbinic traditions also refer to a difference between what was common practice in Judea and the comparatively stricter regulations in Galilee that tolerated no such leniency; see: The Birth of the Messiah: A Commentary on the Infancy Narratives in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke (New York: Doubleday, 1993), 123-24.

[11] It should be noted that the renunciation of marital relations between Mary and Joseph existed uniquely in reference to their immediate situation—the reception of the mystery of the Incarnation. It did not have direct implications for other married couples, not even Elizabeth and Zechariah, who also received the promise of a child, but one born from the natural course of marital relations; see my: “The Sex Life of Joseph and Mary.”

[12] Prat. fas. 19:2.

[13] Ibid., 19-20; cf. John 20:25.

[14] Karl Rahner, Mary, Mother of the Lord (New York: Herder, 1963), 64.

[15] Prat. fas. 9:2.

[16] Origen, Homilies on Luke, Fragments on Luke.

[17] For a feminist theological point of view that tends to favor this theory, see Elizabeth Johnson, Truly Our Sister (New York: Continuum, 2003), 195-99. In contrast to this approach, see the more popular narrative reconstruction of the life of St. Joseph in Gerald Kleba, Joseph Remembered (Irving, TX: Summit, 2000), 20, 151-52.

[18] For a concise review of this development, see Joseph T. Lienhard, St. Joseph in Early Christianity (Philadelphia: Saint Joseph's, 1999), 17-18.

[19] John Meier, after surveying the relevant scriptural evidence, concludes that “from a purely philological and historical point of view, the most probable opinion is that the brothers and sisters of Jesus were his siblings” (332). Richard Bauckham, on the other hand, while recognizing that the interpretation of Meier and others is possible given the evidence, argues that such a conclusion is not therefore necessary or even inevitable. He points out that "the references to the brothers of Jesus, including their association with his mother, in the Gospels and other early Christian literature are perfectly consistent with the view that they were his stepbrothers. Positive evidence that they were the sons of Mary, as well as of Joseph, is lacking.” See: Jude and the Relatives of Jesus in the Early Church (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1990), 24.

[20] Meier certainly goes too far if he intends to restrict the significance of adelphoi to true half-brothers, which in the traditional view would not include sons of Joseph by another wife. However, if Luke can call Joseph Jesus's “father,” knowing he is not, he can also use the word “brother” in a similarly loose way; nor do any of the evangelists have to speak in a way that would not have been normal usage for those not “in” on the secret of the true conception of Jesus. They would have seen "brothers" and called them by that name.

[21] Hom. Luc., 6.3

[22] Ibid., 6.4.

[23] See Ignatius of Antioch, The Epistle to the Ephesians, in Early Christian Writings: The Apostolic Fathers, (New York: Penguin, 1987), 19.1.

[24] Hom. Luc., 6.5; quoting 1 Corinthians 2:6-8.

[25] Ibid., 6.4; humana natura . . . sublimius.

[26] Origen emphasizes that Joseph's role in the economy of the Incarnation is not simply a passive one when he describes the birth of Jesus in the creche: “The shepherds found Joseph, who arranged matters for the Lord's birth,” literally, who was the “dispensator” of the Lord 's birth, the agent of God's providential dispensation, “and they found Mary, who bore Jesus in childbirth, and the Savior himself, ‘lying in a manger’” Hom. Luc., 13.7; commenting upon Luke 2:16.

[27] Hom. Luc., 17.1

[28] Ibid. Cf. Origen, Homilies on Leviticus, 12.4.1

[29] Cf. also Hom. Luc., 19.3, where Origen reiterates this explanation.

[30] Hom. Luc., 17.1.

[31] Ibid., 11.6; quoting Lk 2:4-5.

[32] Ibid.; quoting Rev 20:15 and Phil 4:3.

[33] As St. Luke reminds us, Jesus himself "was obedient to them" (2:51).

[34] In connection with a discussion of St. Bernadette's devotion to St. Joseph, Andrew Doze comments that “what touches upon Joseph is generally carefully hidden and is of no particular interest” in St. Joseph: Shadow of the Father, (New York: Alba, 1992), 60.

[35] Cf. note 30 above.

[36] On the word “Father” as applied to God, see the very helpful explanation at CCC §2779-85, esp. §2779. St. Joseph may well be an avenue to the “purification of hearts” to which this section refers.