Imagine visiting a friend and seeing an attractive, shiny, red apple sitting in a fruit basket. You cannot resist the urge to bite into what should be a juicy treat. Your friend, seeing your mind, invites you to take it. You bring it to your mouth—and find yourself chewing styrofoam. You are—you think—quite rightly upset. What is the meaning of this? Your friend answers that this is the new, trendy fruit among those considered relevant. You see, what matters is that it always looks nice—it is the appearance that makes it fruit. Is your response to declare you are counter-cultural on fruit or to point out that this new trend is not food? Or, do you mean to get people to eat real fruit?

Catholics advocating in the public square tend to use the phrase “counter-cultural” to describe their way of life. Now I understand the point being made. There is a “culture of death,” and we oppose it. But I think that the “counter” terminology is not helpful. After all, Christianity is not defined as being against X, but by being for Christ. As Pope Benedict XVI explained, faith is saying yes to God: “Faith, then, is an assent with which our mind and our heart say their ‘yes’ to God, confessing that Jesus is Lord.” Of course, saying yes to Christ necessitates saying no to certain behaviors, attitudes, and beliefs—but it is a positive reality. By focusing on the “counter” aspect of the Christian life, we are in danger of losing a key point—we are building and preserving a culture. We are not against a culture, but are living and developing a beautiful culture in relationship with Christ by saying “yes” to him. As Pope Benedict XVI argues, “This ‘yes’ transforms life, unfolds the path toward fullness of meaning, thereby making it new, rich in joy and trustworthy hope.”

And critically, the attitude of “counter-culture” gives the relativistic assumptions undergirding the attitudes of many of our prominent academic, political, and artistic institutions too much credit. The moment these groups and institutions abandoned truth, they forfeited the right to be called cultural institutions. Instead, what results is its antithesis: an anti-culture. On the other hand, as Ratzinger shows in Truth and Tolerance, culture is a way that a people live out truth. It is a reference point and school for its members to help them express the truth of the meaning and purpose of life—as experienced and learned by the community and individuals forming that culture: “Culture is the social form of expression, as it has grown up in history, of those experiences and evaluations that have left their mark on a community and have shaped it.”

Implicit in this definition of culture is that cultures will change over time, that is, if they are living cultures. Since they are based on “experiences and evaluations” of an active community, which continue to happen through the course of history. Indeed, because advancing men and women in their knowledge and experience of truth is the purpose of culture, the greater its openness to truth—the more advanced the culture. Cardinal Ratzinger then takes the next step in analyzing this meaning of culture. If culture must contain an element of openness to truth, then a way of life that has the form of culture, but is closed off to the truth, is not a culture.

Instead, it is an anti-culture: If “the question of truth stands outside ‘culture tout court’; . . . is not then this ‘culture tout court [as such]’ rather an anti-culture?” This is a theme he would take up again in his pontificate. For example, at a baptismal ceremony in the Sistine Chapel, he said that “We can say that also in our time a ‘no’ is necessary to the prevailing culture of death, an anti-culture that manifests itself, for example, in the escape in drugs.” Escape from reality, in all its manifestations, is the mark of the anti-culture.

So the agenda to reject objective truth we encounter in our society, that seeks only to vindicate my truth and rejects objective moral and religious limits on human behavior, cannot be said to be a culture. The necessary corollary is that opposing art, education, and politics based on this philosophical framework cannot then be said to be counter-cultural. Rather it is an attempt to replant the roots of culture where barbarism dominates—no matter how sophisticated it may appear.

This year, we have seen this manifested in many ways. Many, quite a few Catholics among them, are trying to build a society that refuses to acknowledge the truth about the coronavirus—and the role of individuals and communities in spreading it. Others are attempting to excuse or dismiss the realities of racial disparities and injustice by refusing to look at facts and blindly focusing on American ideals rather than our realities. We see similar denials in being closed to the truth of the humanity of the unborn as well. This closing off to others—to their experience of truth that they have to offer, merely because they are part of a particular group—is a clear sign an anti-culture is taking hold. It is not the criterion of truth governing our responses to social challenges, but faction and tribalism. Urbanity and a true sense of humanity is lost where these attitudes are inculcated. Instead, people are taught to turn ever more inward and to cut themselves off from their cultural patrimony.

This approach alienates us from ourselves. It prevents those in its grip from living in reality—so ideological living becomes the means to escape from a meaningless existence. And, as we see, ideologies abound—especially in our colleges, universities, and media. These institutions—in their rejection of truth—have rejected their own purpose, mission, and role in our republic. They can no longer be thought of as “cultural” institutions. We should not accept that an outlook on life closed to truth is a culture. To the contrary, we need to point out the anti-culture in our midst: whether it is a will to dominate the life of the unborn or rejecting cultural patrimony because disfavored people made it. Without a commitment to truth, the basis of all healthy relationships, American culture will not survive. Which is to say, it will become impossible to live a common life.

Pope Francis recently highlighted this in his most recent encyclical Fratelli Tutti: “Cultures should be encouraged to be open to new experiences through their encounter with other realities, for the risk of succumbing to cultural sclerosis is always present” (§134). Openness to truth is the mark of culture and authentic cultural development. Indeed, a national culture can only be a benefit to humanity when it is open to all that is true and good in humanity. As Pope Francis points out, “[a] country that moves forward while remaining solidly grounded in its original cultural substratum is a treasure for the whole of humanity” (§137). This also means that an authentic Catholic response to non-Catholic cultures cannot be one of outright rejection, but rather must be one of integration. Too many times, “counter-cultural” becomes a shorthand for rejecting cultures that are different than my own or refusing to see the good in non-Catholic and minority groups.

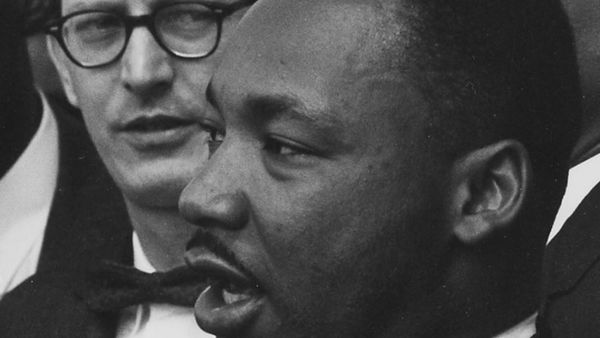

Pope Francis—quoting Saint Irenaeus for inspiration—describes recognizing the truth in these differences as creating a melody. (§58, 283). This sentiment also finds an echo in the thought of Martin Luther King, Jr., who described in his dream that “With this faith [in God’s truth and justice] we will be able to transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood.” It also parallels thoughts shared by Tolkien and the Aztecs, that there is creative power and truth to be found in music or flor y canto—none of which can exist without diversity and difference. Moreover, this approach is affirmed by Holy Writ that encourages us to test and keep all things that are good and true, as Saint Paul tells the Philippians:

For the rest, brethren, whatsoever things are true, whatsoever modest, whatsoever just, whatsoever holy, whatsoever lovely, whatsoever of good fame, if there be any virtue, if any praise of discipline: think on these things (Phil 4:8).

Another pitfall of “counter-cultural” thinking is that some of its proponents view any method of critique or criticism of the past that forms part of today’s culture as something that must be countered. Hence, it becomes the duty of the “counter-culture” warrior to reject all academic or social cultures that provide tools or analysis to examine critically a past that—in the minds of far too many—represents a better time in the life of our country.

Because a culture must be open to truth to advance as a culture and gift to humanity, it must not only be open to other cultures, but it must open to self-criticism. It must not resist efforts at self-examination to root out and reform those aspects that are incompatible with the truth and the proper function of culture—to help men and women embrace a way of life that connects them to their fellow humans and the truth. This process cannot be something that emphasizes glorifying the past over the truth or that avoids conflict. A premium must be placed on authentic discussion and reform: “Authentic reconciliation does not flee from conflict, but is achieved in conflict, resolving it through dialogue and open, honest and patient negotiation” (Fratelli Tutti, §244).

To put a fine point on it, there is nothing Christian or heroic about resisting efforts to critically examine the role of race in forming American institutions and thought. Many Christians, especially in white communities, frame resistance to these important efforts through the lens of a so-called counter-cultural biblical worldview that uses scripture to ignore important self-examination and settle into relativistic thinking: “People I do not like are saying things I do not like—thus, I can fulfill my Christian witness by being against them—regardless of objective criteria; I will be counter-cultural!” But this has things backwards. Any Christian contribution to the culture must be in union, to the greatest degree possible, with our fellow Americans—incorporating what is true and good in their experiences. This must include a willingness to become inculturated in new cultural developments. This is especially true when there is a danger that counter-culturalism is used to reflexively reject cultural developments, simply because they are new, or at least foreign to Christianity as practiced in white communities.

We are called to transform culture according to the criterion of truth. Yet, there are Christians who are invoking a relativistic counter-culturalism to reject authentic cultural developments originating within non-white Christian and other communities that are working to dismantle forms of white supremacy camouflaged as Christianity. Indeed, folks joining in on the counter-cultural movement may, unwittingly, find themselves working against the kind of inculturation all Christians are called to support and encourage. But this is what happens when counter-culturism—rather than Christian inculturation—becomes the guiding light of Christian activity in America.

Hence, some Christians end up unable to utter the very Christian words Black Lives Matter—because they have committed to resisting cultural developments that originate in communities they do not participate in, rather than seeking Christ in all they encounter. The faithful, then, are not called to be agents of a counter-culture. We are called to be the proponents of culture—reminding our fellow Americans that this nation must be built on truth or it will fall. Our approach must be one of dialogue, reconciliation, and growth—while cherishing those aspects of our cultural patrimony that are good and true. We must heed the warning of Lincoln, that great American exponent of moral truth—echoing one of the greatest American truth-tellers: “A house divided against itself cannot stand.”