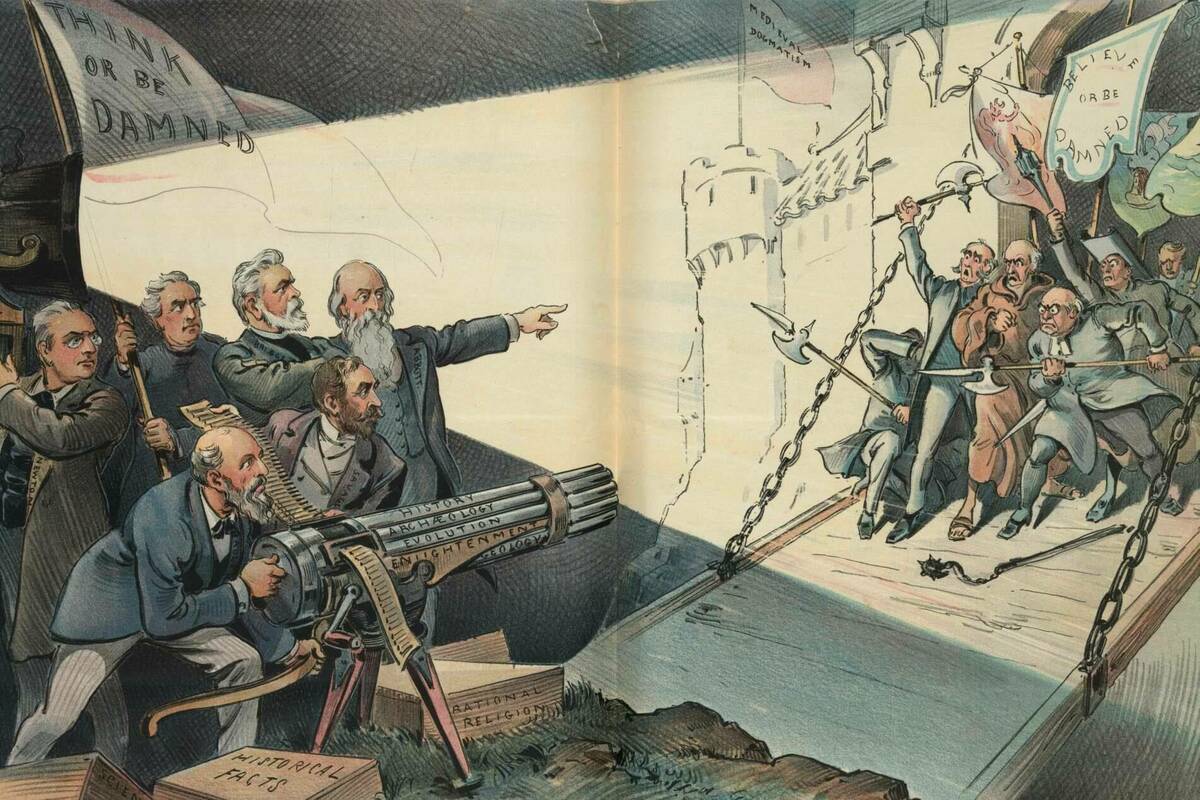

Recent scholarship on the so-called conflict between science and religion has revisited the reception of John William Draper’s History of the Conflict Between Religion and Science (1875) and Andrew Dickson White’s A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom (1896).[1] Indeed, contrary to common perception, Draper and White did not frame science and religion as inherently antagonistic; their positions were far more complex and nuanced.

This complexity is reflected in the diverse public responses to their works, where three predominant patterns emerge.[2] First, the more liberal press heralded Draper and White’s narratives as facilitating a “new Reformation.” They viewed the conflict rhetoric as instrumental in advocating for a distinction between religion and theology, and as a necessary step towards aligning faith with modernity.

In contrast, orthodox religious critics found such separation untenable. For them, faith was inseparable from doctrinal foundations, and they regarded Draper and White’s approach as a direct threat to Christianity, condemning their works as historically inaccurate and ideologically dangerous.

Meanwhile, secularists and atheists appropriated Draper and White’s conflict thesis to advance their own agendas. They interpreted it as an indictment of all religious belief, deploying the language of conflict to erode faith entirely, while finding it paradoxical that Draper and White themselves retained religious convictions.

In retrospect, the anxieties of conservative critics were not entirely misplaced. Here I will investigate how early twentieth-century skeptics appropriated and transformed the conflict thesis into a more secular narrative, significantly broadening its influence.

Organized Freethought in Victorian England

Liberal Protestantism, emerging from the Enlightenment and Romanticism, sought to align religion with contemporary values and scientific understanding. However, this modernization often led to a deeper questioning of religion’s relevance. As James Turner noted, religion was increasingly humanized, making it feasible “to abandon God, to believe simply in man.”[3]

While liberal Protestants adapted their faith, skeptics doubted whether religion retained any substantive value. Leslie Stephen, for instance, critiqued Matthew Arnold’s idea of preserving a “sublimated essence of theology,” questioning whether aesthetic judgments could sustain religious belief in the absence of doctrinal foundations.[4] By the late nineteenth century, these theological concessions helped pave the way for organized secularism to gain societal respectability.

Victorian freethought inherited diverse traditions, particularly the Enlightenment’s commitment to reason and Deist principles. In mid-nineteenth-century England, “secularism” emerged as a philosophical movement, deeply influenced by Thomas Paine’s The Age of Reason (1793). Paine denounced the church as enslaving humanity, advocating for faith in reason and a “Religion of Humanity.” His critique of the Bible as inconsistent and mythological laid the groundwork for radical freethought.

Freethought, tracing its roots to English Deists, found resonance with the Protestant Reformation’s spirit of liberating religious thought from clerical authority.[5] Figures like Richard Carlile, Robert Taylor, Robert Owen, and Charles Southwell were key advocates of freethought, pushing for self-improvement, education, and reform. Carlile, imprisoned for reprinting Paine’s The Age of Reason, saw the printing press as a tool to dismantle the “double yoke” of “Kingcraft and Priestcraft,” using publications to rally against religious and political institutions.

As public opinion grew more tolerant and English society became more stable, freethinkers adopted a less combative stance. By mid-century, leading figures institutionalized irreligion on an unprecedented scale, shifting from radical opposition to a broader, more accepted promotion of secularism.

The Rise of Radical Freethought in the Late Nineteenth Century

The late nineteenth century marked a golden age for radical freethought, during which freethinkers celebrated the liberation of humanity from religious constraints. This movement, led by figures such as George Jacob Holyoake, Charles Bradlaugh, Robert G. Ingersoll, and Joseph M. McCabe, extended its influence across both urban and rural areas through tracts, pamphlets, and magazines.

Interestingly, many freethinkers came from liberal Protestant backgrounds. Scholars like Leigh Eric Schmidt and Christopher Grasso have highlighted the complex relationship between American Protestantism and secularism.[6] For instance, Robert Ingersoll, raised by a liberal Presbyterian minister, eventually favored science over religious belief. Similarly, Samuel P. Putnam’s rejection of theism was shaped by liberal religious ideas from figures like Channing and Emerson. Many American Protestants, navigating from liberalism to infidelity, demonstrated the intersection of Protestantism and secularism, revealing a matrix of rivalry, alliance, and opposition.

In Britain, secularism advanced through both secularists and agnostics. As Bernie Lightman observed, while Thomas H. Huxley used agnosticism to distance himself from atheism, secularists increasingly employed the term to articulate atheistic views. Yet secularists recognized the influence of thinkers like Spencer, Huxley, and Tyndall, even as they criticized agnostics and religious liberals for compromising with religion.

Foote’s Freethinker magazine ridiculed agnostics who attended church, and Bradlaugh condemned figures like Huxley and Spencer for “intellectual vacillation” in failing to promote materialism fully.[7] Darwin, too, faced Bradlaugh’s criticism for what was seen as pandering to religious norms, especially in securing his place in Westminster Abbey.[8]

Ultimately, figures like Bradlaugh were perplexed by agnostics who, in their view, remained too closely tied to religious traditions.

Responses from Agnostics and the Evolving Secularist Landscape

Agnostics often responded to critiques with sharp rebuttals. Thomas Huxley, a leading figure in the agnostic movement, expressed disdain for certain elements within the freethought community. He criticized much of its literature, dismissing what he saw as “heterodox ribaldry,” which he found more distasteful than orthodox fanaticism. Huxley argued that attacking Christianity with scurrilous rhetoric was counterproductive, particularly in England, where such methods were outdated. He harbored a “peculiar abhorrence” for Charles Bradlaugh and his associates.

Bernie Lightman has demonstrated that Huxley and his scientific naturalist peers were repelled by Bradlaugh’s coarse atheism.[9] In correspondence with agnostic Richard Bithell, Huxley declined to support Charles Watts, criticizing freethought literature as repetitive and tiresome. He lamented how such works alienated thoughtful readers, noting: “It is monstrous that I cannot let one of these professed organs of Freethought lie upon my table without someone asking if I approve of this réchauffé of Voltaire or Paine.”[10]

Even moderate freethinkers like George Jacob Holyoake faced discrimination from agnostics. Although Holyoake and Herbert Spencer were longtime friends, Spencer refused Holyoake’s proposal to travel together to America in 1882, fearing it would be seen as an endorsement of Holyoake’s ideas.

Despite this, Holyoake remained a central figure among secularists. Raised in a religious household, his path led him through Christian denominations and eventually to freethought and naturalism. Holyoake often referenced his Christian upbringing to bolster his credibility as a freethinker, using his religious past to enhance his standing as a critic of religion.[11]

Holyoake’s Secularism and Its Impact

During his studies, George Jacob Holyoake encountered Robert Owen’s teachings and joined the Owenite movement as a “social missionary.” By 1843, he had taken over The Oracle of Reason and later founded The Reasoner and Herald of Progress, which became one of the longest-running freethought publications. Throughout the 1850s, Holyoake traveled widely, advocating for social reform and engaging in debates with religious opponents.

In 1849, Holyoake designated The Reasoner as “secular,” and in 1851, coined the term “secularism” to describe his freethought philosophy. He saw secularism as focused on this life, differentiating it from atheism by attracting theists and deists while avoiding the negative connotations of atheism. Holyoake’s secularism centered on social reform rather than religious critique, arguing that salvation, if it existed, was achieved through works, not faith. By promoting secularism, Holyoake sought collaboration with Christian liberals to advance rational morality.

In 1855, Holyoake and his brother Austin established a printing house on Fleet Street to distribute secularist literature. As president of the London Secular Society, Holyoake first met Charles Bradlaugh. Unlike Bradlaugh, Holyoake advocated cooperation among unbelievers, deists, and liberal theists to promote social reform, encouraging atheists to collaborate with liberal clergy to bridge the gap between secularists and Christian liberals.

The Watts Legacy and Secular Propaganda

Most importantly, George Jacob Holyoake’s conciliatory approach to secularism was embraced by Charles Watts and his son, Charles Albert Watts. In 1884, Charles Albert took a significant step toward consolidating secularist efforts by publishing the Agnostic Annual, marking a shift toward greater coordination within the secular movement.

The story of the Watts family’s contribution to freethought is well-documented.[12] Charles Watts, originally a Wesleyan minister’s son, became involved with Bradlaugh’s National Reformer before distancing himself after the “Knowlton affair” and aligning with Holyoake’s ethical humanism. By the 1880s, he took over Austin Holyoake’s printing firm and became a leading rationalist publisher. He eventually left the business to his son, Charles Albert, who sought to attract middle-class unbelievers by promoting agnosticism through the Agnostic Annual. Despite an incident where Huxley publicly disavowed any connection to the Annual, Charles Albert’s relationships with scientific naturalists remained intact.

Charles Albert expanded his efforts by publishing The Agnostic and establishing the “Agnostic Temple” in 1885, offering literature and holding meetings grounded in Spencer’s ideas. That same year, he launched Watts’s Literary Guide, a monthly publication catering to working-class and lower-middle-class audiences. The Guide, which eventually became the New Humanist, featured works from notable figures like Spencer, Huxley, Darwin, and Draper, often depicting the conflict between theology and science in dramatic terms.

Charles Albert also established the Propagandist Press Committee to further the distribution of rationalist literature, successfully expanding both the subscriber base and the visibility of secular publications.

Charles Albert Watts and the Rationalist Press Association

By the late nineteenth century, Charles Albert Watts had founded Watts & Co., and in 1899, his group of rationalists formed the Rationalist Press Association (RPA). Evolving from the Propagandist Press Committee, the RPA sought to promote freedom of thought in ethics, theology, and philosophy while advocating secular education and challenging traditional religious creeds. The RPA published books on religion, biblical criticism, and intellectual progress, emphasizing the perceived conflict between science and religion and advocating secular moral instruction.

The RPA featured works from key figures like Joseph McCabe and John M. Robertson. McCabe, a former Jesuit and prolific author, predicted the downfall of Christianity through scientific naturalism and biblical criticism. His Biographical Dictionary of Modern Rationalists celebrated Draper and White, though he acknowledged that both were theists. McCabe viewed Draper’s work as rationalist literature and praised White’s contribution to rationalism while noting his aim to purify, rather than destroy, Christianity.[13]

John M. Robertson, in his History of Freethought in the Nineteenth Century (1929), referred to Draper’s Intellectual Development as a key contribution to rationalist culture. He argued that Draper’s theism was likely a result of social pressure but acknowledged the naturalistic approach in his work.[14] Other secularists like Joseph Mazzini Wheeler and Samuel P. Putnam similarly recognized Draper and White as freethinkers, with Putnam seeing the Reformation as a precursor to the eventual decline of Protestantism and Roman Catholicism.[15]

In the early twentieth century, the RPA expanded its influence by reprinting “Rationalist classics” using mass-production techniques. Charles Albert Watts collaborated with publishers like Macmillan to produce affordable editions of influential works, distributing six-penny editions of texts by authors such as Darwin, Huxley, Spencer, Paine, and notably Draper and White. Draper’s work, which he saw as a preface to a broader departure from “the faith of the fathers,” was integral to the RPA’s mission to reach a wider audience with rationalist ideas.

Origins of American Freethought

The roots of American freethought trace back to Thomas Paine, whose influence remains foundational. Freethought, as a movement, challenges established beliefs and seeks knowledge, empowering citizens to discern truth and strengthen democracy. Freethinkers advocate reason over passion or outdated customs, overlapping with rationalism, secularism, and skepticism.

Paine’s Common Sense (1776) electrified America and became a rallying cry for revolution. His later works, The Rights of Man (1791) and The Age of Reason (1794), more directly engaged with freethought, with The Age of Reason launching a bold attack on organized religion. Declaring himself a deist, Paine famously stated, “my own mind is my own church.” For his views, he was censored, ridiculed, and ostracized upon his return to America. Even Thomas Jefferson distanced himself. Paine died in 1809, nearly forgotten, his funeral attended by only a few. It was only after the Civil War that freethought gained new life in the U.S.

Secularism, though less organized than in Britain, grew in prominence after the Civil War. James Turner notes that agnosticism emerged as a self-sustaining phenomenon within twenty years.[16] Robert G. Ingersoll, known as the “Great Agnostic,” became the chief exponent of this movement, leading the “Golden Age of Freethought” (1875–1914). Ingersoll’s oratory revived Paine’s tarnished reputation, defending his legacy in essays like Vindication of Thomas Paine (1877). Ingersoll himself opposed religion, which cost him his political career, though he diverged from Paine on issues like socialism.[17]

Ingersoll’s freethought views were complex. Though the son of a minister, he grew to abhor religion, and this stance cost him his political career, which ended while he was still in his twenties. His story reflects the broader challenge faced by the freethought movement, which struggled to gain mainstream acceptance. A mere accusation of being anti-religious could destroy a political candidate’s chances. Ingersoll himself opposed socialism, diverging from some of Paine’s more progressive ideas.

Ingersoll’s death in 1899 marked the end of an era. Unlike Paine, he was neither poor nor forgotten, and even his critics admired his eloquence and ability to connect with audiences across the social spectrum.

Freethinkers Respond to Draper

Freethinkers like Joseph Treat and T. D. Hall seized upon Draper’s History of the Conflict Between Religion and Science as a powerful tool in their efforts to promote secularism and challenge Christianity. Treat, in correspondence with Draper, argued that Christianity had consistently hindered genuine scientific inquiry. He praised Draper’s work for exposing this historical antagonism, asserting that Draper had liberated science from the “bondage” of Christian influence.

Hall, in his pamphlet Can Christianity Be Made to Harmonize with Science?, echoed Treat’s appreciation of Draper’s clarity but critiqued him for stopping short of declaring an outright incompatibility between science and Christianity. Hall insisted that Draper lacked the boldness to acknowledge Christianity’s inevitable collapse in the face of scientific progress. Once Christianity’s central doctrines—such as the Fall, Atonement, and Resurrection—were stripped away, Hall believed, the religion would unravel entirely.

These voices were part of a broader American freethought movement, led by publications like Truth Seeker, founded by D. M. Bennett in 1876. Truth Seeker and groups like the National Liberal League united freethinkers, rationalists, and religious skeptics in advocating for the complete secularization of society.

Across the Atlantic, Draper’s narrative also resonated with British freethinkers, particularly through Charles Albert Watts and the Rationalist Press Association. Watts, via his Watts’s Literary Guide (later New Humanist), treated Draper’s work as a cornerstone for promoting secularism and rationalism. The Rationalist Press Association published works that undermined traditional religious views, with prominent figures like John M. Robertson and Joseph M. Wheeler consistently citing Draper’s analysis to support their campaigns for secular education and religious criticism.

For Robertson, Draper’s naturalistic outlook made his work indispensable to the freethought movement, despite Draper’s own theological leanings. Similarly, Wheeler and Samuel P. Putnam integrated Draper’s arguments into their broader critiques of religion, using his historical analysis not merely as a chronicle of science but as a potent tool in the battle to free society from religious dominance.

Freethinkers on both sides of the Atlantic adopted Draper’s narrative to legitimize their belief in the fundamental incompatibility of science and religion. Through their publications, organizations, and correspondence, they transformed Draper’s work into a weapon for advancing a secular society, one free from the influence of religious institutions.

Freethinkers Respond to White

Freethinkers, as they did with Draper, appropriated Andrew Dickson White’s A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom to further their secular agenda. Publications like The American Free Thought Magazine praised White’s work for illustrating the historical struggle to modernize Christian theology, framing it as a triumph of science over religious dogma. The magazine argued that White’s history was essential for any freethinker’s library, not merely for cataloging religious errors but for celebrating science’s victories.

In England, thinkers like Alfred W. Benn placed White alongside luminaries such as Buckle, Draper, and Lecky. However, Benn expressed frustration with White’s reluctance to fully reject Christianity, arguing that his conclusions logically pointed to the abandonment of its doctrines. For Benn and others, White’s work symbolized the deepening conflict between rational thought and religious belief.

White’s work also drew criticism from prominent atheists like Edward Payson Evans and Elizabeth Edson Gibson Evans. They were perplexed by White’s attempts to reconcile religion and science. Elizabeth criticized White’s refusal to fully disbelieve in religion, insisting that science had consistently debunked religious claims. Edward accused White of being overly generous to religion, contending that the conflict between science and faith was irreconcilable.

This tension was further evident in White’s interactions with Robert G. Ingersoll, the renowned agnostic orator. While Ingersoll appreciated White’s contribution to intellectual openness and his critique of religious authority, he saw White’s lingering religious sentiment as unnecessary. Ingersoll dismissed Christianity as not worth saving, sarcastically asking why God would make truth-seeking safe now after allowing it to be dangerous for centuries.

Despite White’s reluctance to fully embrace secularism, freethinkers eagerly adopted his work to undermine religious institutions. Charles Albert Watts, a prominent British secularist, published extensive reviews of White’s book in the Watts’s Literary Guide, encouraging White to write for the secularist Annual. Although White declined, secularists continued to use his work to advance their cause.

White himself was unsettled by this reception. He had aimed to provide a balanced critique, addressing both religious “scoffers” like Ingersoll and the religious “gush” of figures like John Henry Newman. In private, he expressed to his secretary George Lincoln Burr that he sought to present “the truth as it is in Jesus,” but both religious and irreligious readers often misinterpreted his work as an attack on faith itself.

In conclusion, while White’s intentions were more conciliatory than Draper’s, freethinkers and secularists embraced his narrative as part of their broader efforts to secularize society. Regardless of White’s personal beliefs, his work became a cornerstone in the intellectual campaign to discredit religious authority and advance rationalism.

Joseph McCabe and the “Land of Bunk”

One of the most significant secularists to appropriate Draper and White’s conflict thesis was Joseph McCabe, a former Franciscan monk turned outspoken atheist. McCabe believed that science and technology would not only solve society’s problems but also lead to a more rational and egalitarian world. His translation of Ernst Haeckel’s The Riddle of the Universe (1900) introduced Haeckel’s ideas to English-speaking audiences, and despite McCabe’s lack of formal scientific training, this association lent authority to his writings. A prolific author, McCabe produced over 200 books on science, history, and religion, championing evolutionary thought and forecasting Christianity’s inevitable demise in the face of modern science.

McCabe’s personal journey mirrored his intellectual transformation. Raised in a Franciscan monastery, where he took the name Brother Antony, McCabe was tormented by doubts about Christianity. His experiences in the monastery, marked by physical suffering and intellectual conflict, eventually led him to leave the priesthood in 1895. His account, Twelve Years in a Monastery (1897), detailed his disillusionment with the Church and marked his formal break with religion. From that point on, McCabe became a relentless advocate for atheism, insisting that science, not religion, held the answers to life’s great questions.

McCabe’s partnership with Kansas-based publisher Emanuel Haldeman-Julius was one of the defining collaborations of his career. Haldeman-Julius, known for his “Little Blue Books” series, provided affordable and accessible literature on topics ranging from politics to science. McCabe became the series’ most prolific contributor, writing 134 Little Blue Books and over 100 Big Blue Books. Haldeman-Julius praised McCabe as “the greatest scholar in the world,” crediting his works with advancing humanity’s cultural progress.

This partnership gave McCabe a renewed sense of purpose, especially after facing personal and professional setbacks in Britain. By 1925, after separating from his wife and severing ties with key British publishers, McCabe found both financial stability and intellectual validation through his collaboration with Haldeman-Julius. Over the following years, McCabe produced an immense body of work, earning substantial income while continuing to challenge religious orthodoxy.

One of McCabe’s most influential works, The Conflict Between Science and Religion (1927), essentially echoed Draper’s narrative but with a tone of triumph. McCabe confidently predicted that future historians would regard the denial of the science-religion conflict as laughable. He argued that “science has, ever since its birth, been in conflict with religion,” with Christianity as its “most deadly opponent.”

McCabe’s critique extended beyond traditional religious beliefs. He reserved particular scorn for modernist and liberal theologians, dismissing their attempts to reconcile Christianity with science as “the veriest piece of bunk that Modernism ever invented.” In McCabe’s view, rejecting Christianity’s core doctrines—whether through scientific reinterpretation or otherwise—was tantamount to rejecting Christianity entirely. For him, “progressive religion” was a contradiction, and those who embraced it were deluding themselves.

Ironically, McCabe used arguments similar to those of conservative Christians, accusing liberal theologians like Shailer Mathews of undermining Christianity’s foundations. He argued that attempts to reconcile science with religion were futile, given that science operated as a unified field while religion had never achieved such coherence. McCabe quipped that applying science to religion would require addressing “three hundred different collections of religious beliefs,” making any reconciliation impossible.

In McCabe’s final analysis, whether one adhered to orthodox Christianity or its modernist variants, the conflict with science was inevitable. He contended that modernists, in reducing God to abstractions like “Cosmic Force” or “Vital Principle,” had gutted religion of any meaningful content. Both fundamentalists and modernists, McCabe concluded, inhabited the same “land of bunk,” unable to recognize the inherent incompatibility between science and religion.

Emanuel Haldeman-Julius and the Philosophy of the “Little Blue Books”

Emanuel Haldeman-Julius, later known as the “Henry Ford of publishing,” was born to Jewish immigrants in Philadelphia and grew up in a secular household. Though his formal education ended in the eighth grade, his passion for reading and self-education shaped his early worldview. Influenced by thinkers like Omar Khayyam, Voltaire, and Robert Ingersoll, he developed a deep rejection of religion, identifying as a materialist and dismissing the notion of an afterlife. His early exposure to cheap pamphlets like The Rubaiyat and The Ballad of Reading Gaol ignited his desire to make literature accessible to the masses.

In 1915, Haldeman-Julius moved to Girard, Kansas, where he worked for the socialist newspaper Appeal to Reason. After marrying Annie Haldeman, niece of social reformer Jane Addams, he purchased the paper and began distributing pamphlets, marking the beginning of his publishing empire. His vision of providing affordable, pocket-sized booklets on a wide range of topics took shape in the Little Blue Books series, which covered literature, philosophy, science, and religion, and initially sold for just five cents. These pamphlets aimed to provide a “university in print” for working- and middle-class readers, offering access to ideas traditionally reserved for the educated elite.

The Little Blue Books became a massive success, with over 500 million copies sold. Haldeman-Julius’s marketing genius—using sensational ads like “Books are cheaper than hamburgers!”—helped spread his freethought and socialist ideas. He published works by influential authors such as Shakespeare, Twain, Darwin, and Emerson, alongside freethought titles like Why I Am an Atheist and The Bible Unmasked, which challenged religious orthodoxy. His goal was to democratize knowledge and encourage critical thinking, particularly against religious and political authority.

Central to Haldeman-Julius’s success was his collaboration with Joseph McCabe, a former monk turned atheist and prolific writer. McCabe contributed significantly to the Little Blue Books, with works like The Story of Religious Controversy, a key text that attacked Christianity and promoted a rationalist worldview. Together, McCabe and Haldeman-Julius saw their work as a means to combat what they viewed as the intellectual stagnation of religious dogma.

Despite the series’ success, Haldeman-Julius faced criticism for the mixture of high-quality literature with less scholarly content. H. L. Mencken famously remarked that the Little Blue Books contained “extremely good books” alongside “unutterable drivel.” However, the series continued to thrive, offering over 2,000 titles on a range of subjects from classic literature to freethought.

Haldeman-Julius’s own contributions to the series often included sharp critiques of religion. He dismissed attempts to reform religion as futile, arguing that modernism was simply a way to escape the intellectual difficulties of faith without embracing rationalism. He viewed religion as “medieval” and atheism as “modern,” believing that science and the social sciences provided the tools to debunk religious beliefs. Pamphlets like Is Science the New Religion? and The Meaning of Modernism reflected his disdain for attempts to reconcile science and faith, which he saw as inherently contradictory.

At its peak, Haldeman-Julius’s publishing empire became the largest mail-order publishing house in the world, based in the small town of Girard, Kansas. By 1921, he was selling over a million Little Blue Books each month, reflecting the widespread appetite for accessible education and freethought. He argued that the success of his series demonstrated a growing tendency toward skepticism and intellectual independence in America.

However, the post-World War II rise of conservatism and the anti-communist fervor of the McCarthy era led to a decline in the influence of Haldeman-Julius’s publications. He continued to publish controversial pamphlets, including The F.B.I.: The Basis of an American Police State (1948), but faced increasing harassment from the government. In 1951, after being convicted of tax evasion, Haldeman-Julius was found dead under mysterious circumstances.

Despite his personal and financial struggles in his later years, Haldeman-Julius’s impact on American intellectual life was profound. His Little Blue Books brought sophisticated ideas and literature to the masses, helping to foster a culture of skepticism, critical thinking, and freethought in early twentieth-century America.

Conclusion

Thus by the early twentieth century, Draper, White, and the scientific naturalists had lost control of their attempts to reconcile science and religion. Their narratives, once intended to bridge the two fields, became powerful weapons for secularists in the battle for authority in public and political spheres, wielded against religion. Though some secularists later reconverted to forms of Christianity, the damage was done. The conflict narrative had taken hold, and many minds came to view the relationship between science and religion as one of perpetual antagonism. In time, historians of science would attribute to Draper, White, and the scientific naturalists the founding of what became known as the Conflict Thesis.

Reactions to Draper, White, and other scientific naturalists were varied and complex. Religious liberals were among the protagonists, many of whom went to great lengths to defend these figures against accusations of atheism and materialism. These liberal leaders sought to modernize Christianity, ensuring it remained in step with the emerging scientific worldview, hoping this would stem the erosion of belief. Some even argued that Christianity itself was outdated, suggesting that both physical and historical sciences had revealed a new religion or theology. Religious agnostics and scientific naturalists, in turn, were not only conciliatory toward liberal Christianity but also drew spiritual inspiration from its tenets, incorporating them into their own work.

The antagonists included not only conservative or orthodox theologians but also rationalists and secularists, all of whom rejected the so-called reconciliation between science and religion, though for different reasons. The efforts of the “peacemakers” ultimately failed. Secularists did not accept the redefinitions of religion and the reconstructions of Christianity that men like Draper and White proposed. A paradox emerged in their attempt to reconcile science and religion: narratives meant to demonstrate religion's progress through scientific investigation were instead seized by rationalists and secularists, who used them as a weapon against all religion, aiming to eradicate it entirely.

[1] See James C. Ungureanu, Science, Religion, and the Protestant Tradition: Retracing the Origins of Conflict (UPP, 2019).

[2] For a more detailed analysis, see James C. Ungureanu, “Science and Religion in the Anglo-American Periodical Press, 1860-1900: A Failed Reconciliation,” Church History, 88:1 (2019): 120-149.

[3] James Turner, Without God, Without Creed, 261.

[4] Leslie Stephen, Studies of a Biographer, 2 vols. (London: Duckworth and Co., 1898), 2.76-122.

[5] See Edward Royle, “Freethought: The Religion of Irreligion,” in D.G. Paz (ed.) Nineteenth-Century English Religious Traditions: Retrospect and Prospect (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1995), 171-196.

[6] Leigh Eric Schmidt, Village Atheists: How America’s Unbelievers Made Their Way in a Godly Nation (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2016); Christopher Grasso, Skepticism and American Faith: From the Revolution to the Civil War (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).

[7] Louis Greg, “The Agnostic at Church,” Nineteenth Century, vol. 11, no. 59 (Jan 1882): 73-76; Freethinker, vol. 1 (Jan 15, 1882).

[8] Cited in James Moore, The Darwin Legend (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 1994), 64-65.

[9] Lightman, Victorian Popularizers of Science, 264.

[10] Richard Bithell to T.H. Huxley, 20 Sept 1894 and T.H. Huxley to Richard Bithell, 22 Sept 1894, T.H Huxley Collection, Imperial College Archives, Box 11.

[11] See McCabe, Life and Letters of George Jacob Holyoake, 1.1-17, 18-36; George Jacob Holyoake, The Trial of George Jacob Holyoake on an indictment for blasphemy (London: Printed and Published for “The Anti-Persecution Union,” 1842), 20-21.

[12] F.J. Gould, The Pioneers of Johnson’s Court: A History of the Rationalist Press Association from 1899 Onwards (London: Watts & Co., 1929); A.G. Whyte, The Story of the R.P.A., 1899-1949 (London: Watts & Co., 1949).

[13] Joseph McCabe, A Biographical Dictionary of Modern Rationalists (London: Watts & Co, 1920), 221-222, 886-887.

[14] J.M. Robertson, A History of Freethought in the Nineteenth Century, 2 vols. (London: Watts & Co., 1929), 1.261-262. See also A Short History of Freethought: Ancient and Modern (London: Swan Sonnenschein & Co., 1899), 420. By 1906, Robertson revised and expanded this work into a massive two-volume edition (London: Watts & Co., 1906). In this edition Robertson listed Draper’s Intellectual Development and History of Conflict as general histories of freethought.

[15] J.M. Wheeler, A Biographical Dictionary of Freethinkers of All Ages and Nations (London: Progressive Publishing Co., 1889), 112, 332; S.P. Putnam, 400 Years of Freethought (New York: The Truth Seeker Company, 1894), 47-50.

[16] Turner, Without God, without Creed, 171.

[17] See Martin E. Marty, The Infidel: Freethought and American Religion (Cleveland: Meridian Books, 1961); Paul A. Carter, The Spiritual Crisis of the Gilded Age (DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 1971); and Eric T. Brandt and Timothy Larsen, “The Old Atheism Revisited: Robert G. Ingersoll and the Bible,” Journal of the Historical Society, vol. 11, no. 2 (2011): 211-238.