The Church cannot escape the tragedy inherent in all things human, which arises from the fact that infinite values are bound up with what is human and consequently imperfect. Truth is bound up with human understanding and teaching; the ideal of perfection with its human presentation; the law and form of the community with their human realization; grace, and even God Himself—remember the Sacrifice of the Mass—bound up with actions performed by men. The Infinitely Perfect blends with the finite and imperfect. This, if we dare say it, is the tragedy of the Eternal himself, for he must submit himself to all this if he is to enter the sphere of humanity. And it is the tragedy of man, for he is obliged to accept these human defects, if he would attain the Eternal. All this is as applicable to the Church, as to every institution that exists among human beings. But in her case it has an additional poignancy.

For the highest values are here involved. There is a hierarchy of values, and the higher the value in question, the more painfully will this tragic factor be felt. Here, however, we are concerned with holiness, with God’s grace and truth, with God himself. And we are concerned with man’s destiny which depends on this divine reality—the salvation of his soul. That the state should be well ordered is, of course, of great importance, and so is a well-constructed system of the natural sciences; but in the last resort we can dispense with both. But the values bound up with the Church are as indispensable on the spiritual plane as food in the physical order. Life itself depends upon them. My salvation depends upon God; and I cannot dispense with that. If, however, these supreme values, and consequently the salvation of my soul, are thus intimately bound up with human defects, it will affect me very differently from, for instance, the wrecking of a sound political constitution through party selfishness.

But there is a further consideration. Religion stands in a unique relation to life. When we look more closely, we see that it is itself life; indeed, it is fundamentally nothing but that abundant life bestowed by God. Its effect, therefore, is to arouse all vital forces and manifestations. As the sun makes plants spring up, so religion awakens life. Within its sphere everything, whether good or bad, is at the highest tension. Goodness is glorified, but evil intensified, if the will does not overcome it. The love of power is oppressive in every sphere, but in the religious most of all. Avarice is always destructive, but when it is found in conjunction with religious values or in a religious context, its effect is peculiarly disastrous. And when sensuality invades religion, it becomes more stifling than anywhere else. If all this is true, the human tragedy is intensified in religion, since any shortcoming is here a heavier burden and more painfully felt.

Yet a further point. In other human institutions the realization of spiritual values is less rigid. They leave men free to accept or refuse a particular embodiment. The value represented by a well-ordered political system, for instance, is indeed bound up with particular concrete states. But every man is free to abandon any given state and to attach himself to another, whenever he has serious grounds for taking the step. In the Church, however, we must acknowledge not simply the religious value in the abstract, nor the mere fact that it is closely knit with the human element, but that it is bound up with this, and only this particular historic community. The concrete Church, as the embodiment of the religious value demands our allegiance. And even so, we have not said enough. The truth of Christianity does not consist of abstract tenets and values, which are “attached to the Church.” The Truth on which my salvation depends is a Fact, a concrete reality. Christ and the Church are that truth. He said: “I am the truth.” The Church, however, is his Body. But if the Church is herself Christ, mystically living on; herself the concrete life of truth and the fullness of salvation wrought by the God-man; and if the values of salvation cannot be detached from her and sought elsewhere, but are once and for all embodied in her as a historical reality, the tragedy will be correspondingly painful, that this dispenser of salvation is so intimately conjoined with human shortcomings.

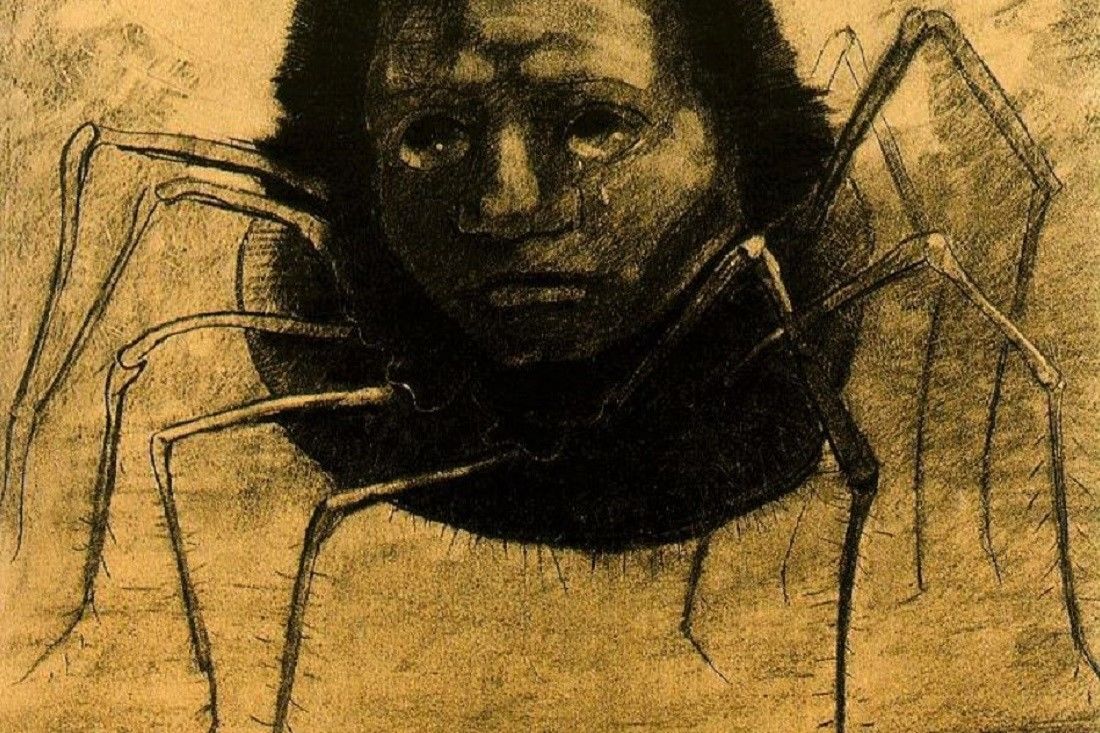

Therefore, just because the Church is concerned with the supreme values, with the salvation of the soul, because religion focuses the forces of life and thus fosters everything human, both good and bad, because we are here confronted with a historical reality which as such binds us and claims our allegiance, the tragedy of the Church is so intense. So intense is it that we can understand that profound sadness which broods over great spirits. It is the tristezza così perenne [“this persistent sadness”]. which is never dispelled on earth, for its source is never dry. Indeed, the purer the soul, the clearer its vision, and the greater its love for the Church, the more profound will that sorrow be.

This tragedy is an integral part of the Church’s nature, rooted in her very essence, because “the Church” means that God has entered human history; that Christ, in his nature, power, and truth, continues to live in her with a mystical life. It will cease only in Heaven, when the Church militant has become the Church glorified. And even there? What are we to say of the fact that a particular man who should have become a saint and who could have attained the full possession of God, has not done so? And who will dare to say that he has fully realized all he might have been? We are confronted here by one of those ultimate enigmas before which human thought is impotent. Nothing remains but to turn to a power which is bound by no limits, and whose creative might “calls those things that are not, as those that are”—the Divine Love. Perhaps the tragedy of mankind will prove the opportunity for that love to effect an inconceivable victory in which all human shortcomings will be swallowed up. It has already made it possible for us to call Adam’s fault “blessed.” That the love of God exceeds all bounds and surpasses all justice is the substance of our Christian hope. But for this very reason what we have already said remains true.

To be a Catholic, however, is to accept the Church as she is, together with her tragedy. For the Catholic Christian this acceptance follows from his fundamental assent to the whole of reality. He cannot withdraw into the sphere of pure ideas, feelings, and personal experience. Then, indeed, no “compromises” would be any longer required. But the real world would be left to itself, that is, far from God. He may have to bear the reproach that he has fettered the pure Christianity of the Gospel in human power and secular organization, that he has turned it into a legal religion on the Roman model, a religion of earthly ambitions, has lowered its loftiest standards addressed to a spiritual elite to the capacity of the average man, or however the same charge may be expressed. In fact, he has simply been faithful to the stern duty imposed by the real world. He has preferred to renounce a beautiful romanticism of ideals, noble principles, and beautiful experiences rather than forget the purpose of Christ—to win reality, with all that the word implies, for the Kingdom of God.

Paradoxical as it may seem, imperfection belongs to the very essence of the Church on earth, the Church as a historical fact. And we may not appeal from the visible Church to the ideal of the Church. We may certainly measure her actual state by what she should become, and may do our best to remove her imperfections. The priest is indeed bound to this task by his ordination, the layman by Confirmation. But we must always accept the real Church as she actually is, place ourselves within her, and make her our starting point.

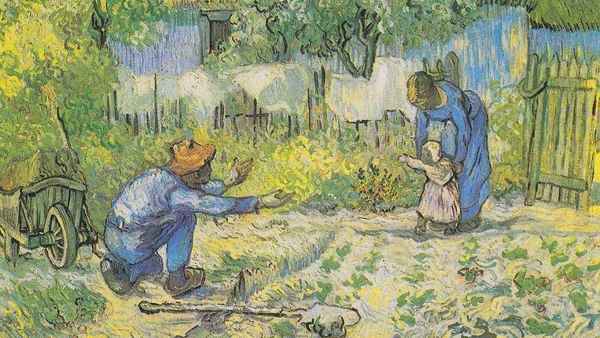

This, of course, presupposes that we have the courage to endure a state of permanent dissatisfaction. The more deeply a man realizes what God is, the loftier his vision of Christ and His Kingdom, the more keenly will he suffer from the imperfection of the Church. That is the profound sorrow which lives in the souls of all great Christians, beneath all the joyousness of a child of God. But the Catholic must not shirk it. There is no place for a Church of aesthetes, an artificial construction of philosophers, or congregation of the millennium. Man needs a Church that is a church of human beings; divine, certainly, but including everything that goes to make up humanity, spirit and flesh, earth. For “the Word was made Flesh,” and the Church is simply Christ, living on, as the content and form of the society He founded. We have, however, the promise that the wheat will never be choked by the tares.

Christ lives on in the Church, but Christ crucified. One might almost venture to suggest that the defects of the Church are His cross. The entire Being of the mystical Christ—His truth, His holiness, His grace, and His adorable person—are nailed to them, as once His physical body to the wood of the Cross. And he who will have Christ must take His cross as well. We cannot separate Him from it.

I have already pointed out that we shall only have the right attitude towards the Church’s imperfections when we grasp their purpose. It is perhaps this—they are permitted to crucify our faith, so that we may sincerely seek God and our salvation, not ourselves. And that is the reason why they are present in every age. There are those indeed who tell us that the Early Church was ideal. Read the sixth chapter of the Acts of the Apostles. Our Lord had scarcely ascended to Heaven when dissension broke out in the primitive community. And why? The converts from paganism thought that the Jewish Christians received a larger share than they in the distribution of food and money. This surely was a shocking state of affairs? In the community through which the floods of the Spirit still flowed from the Pentecostal outpouring? But everything recorded in Holy Scripture is recorded for a purpose. What should we become if human frailties actually disappeared from the Church? We should probably become proud, selfish, and arrogant; aesthetes and reformers of the world. Our belief would no longer spring from the only right motives, to find God and secure eternal happiness for our souls. Instead, we should be Catholics to build up a culture, to enjoy a sublime spirituality, to lead a life full of intellectual beauty. The defects of the Church make any such thing impossible. They are the Cross. They purify our faith.

Moreover, such an attitude is at bottom the only constructive type of criticism, because it is based on affirmation. The man who desires to improve a human being must begin by appreciating him. This preliminary acknowledgment will arouse all his capacities of good and their operation will transform his faults from within. Negative criticism, on the contrary, is content to point out defects. It thus of necessity becomes unjust and puts the person blamed on the defensive. His self-respect and justifiable self-defense ally themselves with his faults and throw their mantle over them. If, however, we begin by accepting the man as a whole and emphasize the good in him, all his capacities of goodness, called forth by love, will be aroused and he will endeavor to become worthy of our approval. The seed has been sown, and a living growth begun which cannot be stayed.

We must, therefore, love the Church as she is. Only so do we truly love her. He alone genuinely loves his friend who loves him as he is, even when he condemns his faults and tries to reform them. In the same way we must accept the Church as she is, and maintain this attitude in everyday life. To be sure we must not let our vision of her failings become obscured, least of all by the artificial enthusiasm aroused by public meetings or newspaper articles. But we must always see through and beyond these defects her essential nature. We must be convinced of her indestructibility and at the same time resolved to do everything that lies in our power, each in his own way and to the extent of his responsibility, to bring her closer to her ideal. This is the Catholic attitude towards the Church.

Editorial Note: Today marks the 51st anniversary of Romano Guardini's death. This essay is an excerpt from his The Meaning of the Church, courtesy of Cluny Media.