Each year, on the night of October 3, gatherings around the world celebrate the “Transitus of St. Francis of Assisi.” This vigil celebration anticipates the Poor Man of Assisi’s feast day. It puts before its participants the transition of Brother Francis from this life, through Sister Bodily Death, onward to the life transformed. While its form and shape might vary from place to place, the transitus can draw a person and community closer in memory and spirit to the life and death of Francis the Poverello: the little Poor One.

His life was one marked by a reverence for the beauty of creation. It was also a life marked by the signs of Christ Crucified. This is a provocative and rich juxtaposition. The man who dressed and kissed the leper’s sores would exalt the Creator through the stars and Sister Moon, who in the “Canticle of the Creatures” Francis praises as “precious and beautiful.” God should be praised through Brother Fire, for he is “beautiful and cheerful.” The beauty of the created order—both the simple and awe-inspiring—and the sorrowful sight of the Crucified seem from a certain vantage point an uneasy and tenuous tandem. Even in Francis’s own person we see this tension. As Dante sees him in Paradise, Francis, “in his love, shone like the Seraphim,” though he “did not care that he went in rags, a figure of passing scorn.”

In addition to this apparent contrast is the movement in Francis’s life from when, as he said, he “was in sin,” to the point when he says he “left the world.” In reference to this, shortly before the death that the transitus recalls, Francis dictated his “Testament,” which bears these well-known words:

The Lord granted me, Brother Francis, to begin to do penance in this way: While I was in sin, it seemed very bitter to me to see lepers. And the Lord Himself led me among them and I had mercy upon them. And when I left them that which seemed bitter to me was changed to sweetness of soul and body; and afterward I lingered a little and left the world.

This movement from bitterness to sweetness is both perplexing and profound. Herein we see a shift in Francis’s form of life, in what he knows to be good and beautiful.

All this raises two distinct but related questions. First, how can we account for the process of Francis’s conversion in aesthetic terms? What makes for the radical reversal of the bitter and sweet? Second, when taking into account his life after his time with the lepers, after the most overt turns of his conversion, can we see his glorying in the beauty of creation as being consonant with his love of the naked and crucified Christ? Which is to ask, was the Poverello’s love of beauty put to the side when carrying out his devotional life and charitable efforts? Or, did his relation to the Incarnate and Crucified Jesus deepen and alter his appreciation for, and understanding of the beautiful in the created order, and vice-versa?

Love “to the Very End”

A modern work from Joseph Ratzinger can aid this attempt to untangle these matters. In his 2002 essay titled “The Contemplation of Beauty,” Ratzinger provides a more theoretical treatment of the present problem that can, in turn, illuminate St. Francis’s lived experience.

Ratzinger begins his essay remarking on a striking paradox present in the Liturgy of the Hours as found in the season of Lent. For Psalm 45 there are two different antiphons, one used in Holy Week, and one used for the rest of the year. Their difference is stark. The antiphon used every week but Holy Week reads: “You are the fairest of the children of men and grace is poured upon your lips.” For Holy Week, the antiphon channels Isaiah 53: “He had neither beauty, no majesty, nothing to attract our eyes, no grace to make us delight in him.”

With the first antiphon comes a sense of grace, glory, and beauty. It is not just an external attractiveness at work here. As Ratzinger puts it:

The beauty of Truth appears in him, the beauty of God himself who draws us to himself and, at the same time captures us with the wound of Love, the holy passion (eros) that enables us to go forth . . . to meet the Love who calls us.

Yet, how can this be reconciled with the second antiphon? The fairest of the children of men is now repellent. Ratzinger identifies this as a paradox, an instance of “contrast and not contradiction.”

This juxtaposition helps Ratzinger shape a question: is it beauty or ugliness that “leads us to the deepest truth of reality?” As he sums up a response, the God that manifests himself in Christ—in the altered appearance of the Crucified—reveals himself as love “to the end.” The one who believes in this God, knows “that beauty is truth and truth beauty,” but that this entails the embracing of “offence, pain, and even the dark mystery of death.”

Ratzinger then looks to the Phaedrus, where he sees Plato depicting beauty as an “emotional shock” that makes a person come out of himself, drawing him toward that which “is other than himself.” Having lost our “original perfection,” we seek healing. Beauty causes us to suffer, it prevents us “from being content with just daily life.” Drawing on the Symposium, Ratzinger incorporates the claim that “lovers do not know what they really want from each other.” They want more than just amorous affection, yet they remain unable to articulate what this further mysterious thing is really.

Ratzinger next draws on the work of the Orthodox saint and theologian Nicholas Cabasilas to further plumb the depths of this fertile tension. In his The Life in Christ, Cabasilas teaches that “it is knowing that causes love and gives birth to it.” A person must first know how beautiful something is before he can love it. Unlike Ratzinger, Cabasilas is directly concerned with the effects of the washing of baptism on those that have loved to the very end, the martyrs. In Cabasilas’s own words, he is asking: “what is the cause of their love, what [did they experience] to make them love in this way, and whence they received the fire of love”?

Considering that love follows knowledge, Cabasilas sees there being two paths to knowledge, the one hearsay, the other personal experience. The first is lacking since it does not encounter a thing directly, but only by the word of another, which is an “image of the thing itself.” Learning by hearsay, “we receive an uncertain and dim image of [the thing] through what it has in common with other things, and by it measure our desire for the thing itself.” Since we do not encounter the thing itself, we do not experience the thing’s “proper effect,” and we therefore do not “love it to the extent that it is a worthy object of love.”

Alternatively, by experience, “the form itself encounters the soul and incites desire, as though it left an imprint corresponding to the good.” Since hearsay involves knowing something as it shares a commonality with other things, and elicits a love proportional to this mode of knowing, and since to Christ, as Cabasilas says, “nothing like Him may be found, nothing which He has in common with others”:

When men have a longing so great that it surpasses human nature and eagerly desire and are able to accomplish things beyond human thought, it is the Bridegroom who has smitten them with this longing. It is He who has sent a ray of His beauty into their eyes. The greatness of the wound shows the dart which has struck home, the longing indicates who has inflicted the wound.

Ratzinger continues with a gloss: “being struck and overcome by the beauty of Christ is a more real, more profound knowledge than mere rational deduction.” This does not negate the value and place of precise theological language and reflection, this is all still necessary. This theological work would be rendered without worth, however, were the encounter of the heart with beauty, “as a true form of knowledge,” negated or ignored. This path of beauty is “the very way in which reason is freed from dullness and made ready to act.” The experience of the beautiful for Ratzinger also provides the person with a more authentic criterion of truth and goodness.

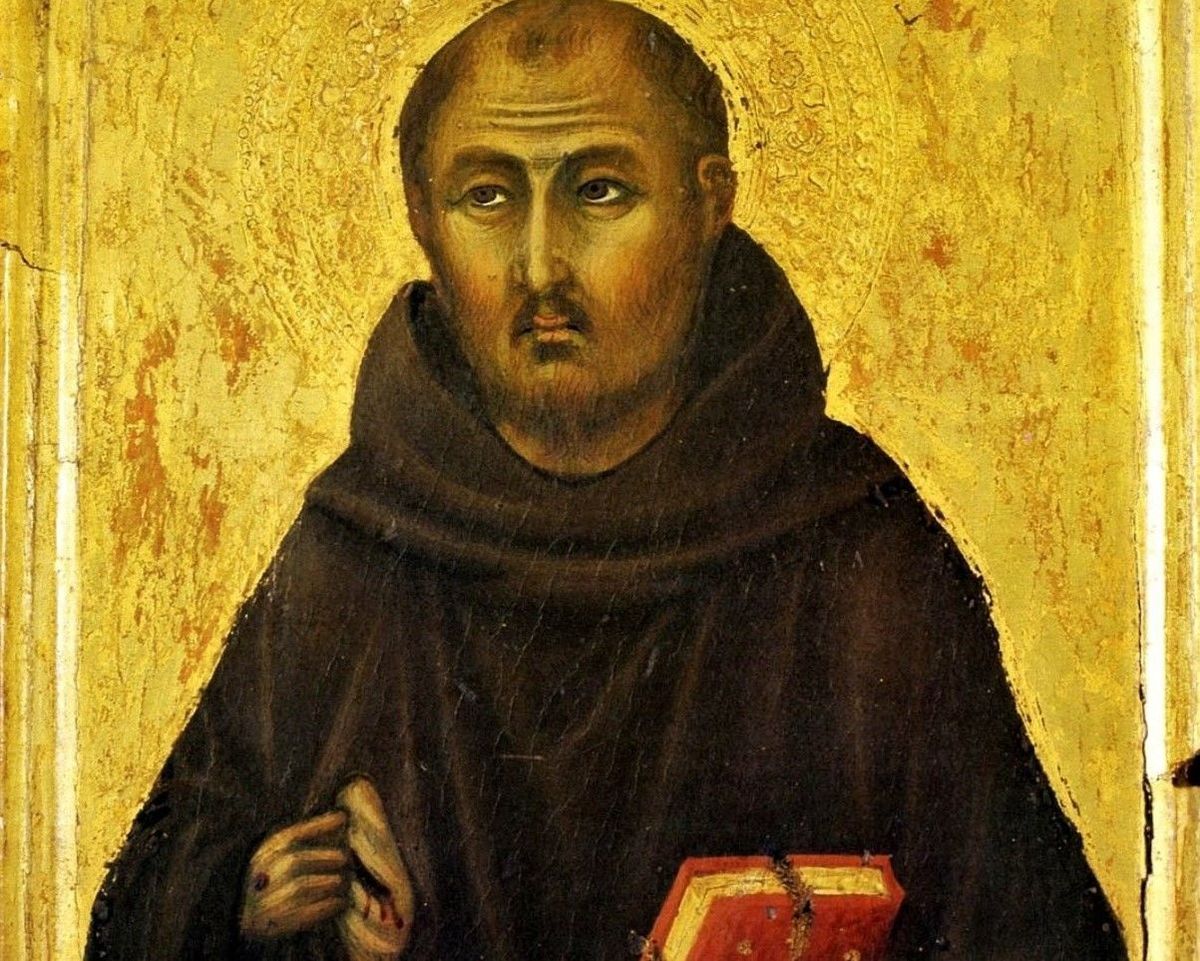

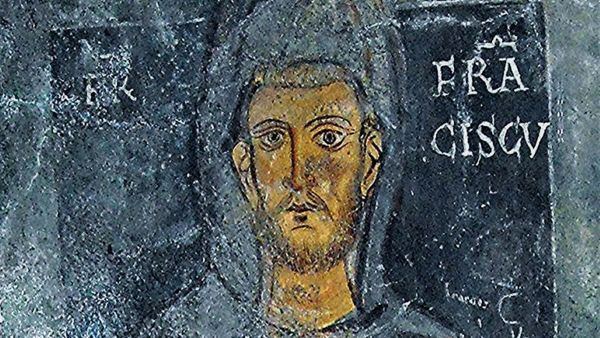

Thinking of the icon—here the Cross of San Damiano, so important to St. Francis, comes to mind—Ratzinger says that what is required when viewing the image is an “inner perception” that frees itself “from the impression of the merely sensible, and in prayer and ascetical effort [acquires] a new and deeper capacity to see.” This involves a purification of the vision and the heart. This inner way is a path toward both beauty and truth. It allows someone to pass from the purely external to the “profundity of reality.” With this enriched perception, the person is able to more fully recognize the “glory of God.”

But what of the naked and crucified Jesus? Does he not seem to undermine the ideal of harmonious beauty, at least as previously conceived? Ratzinger says that, no, in Christ’s passion, “the experience of the beautiful has received new depth and new realism.” In Christ’s marred visage—spat upon and plucked—in this disfigured face “appears the genuine, extreme beauty: the beauty of love that goes ‘to the very end.’”

Now, there is the danger of being lured in by “a beauty that is deceptive and false, a dazzling beauty that does not bring human beings out of themselves to open them to the ecstasy of rising to the heights, but indeed locks them entirely into themselves.” This beauty does not elicit a “longing for the Ineffable, readiness for sacrifice, the abandonment of the self, but instead stirs up the desire, the will for power, possession and pleasure.” It is the task of the artist to protect against this alluring illusion and put forward an authentic encounter with the beautiful. It is Christ Crucified, more importantly, who stands as the antidote to the allure of deceptive beauty. And it is exactly this healing that the young Francis of Assisi experienced in his conversion.

Stumbling toward Fame and Glory

Prior to his conversion, Francis can be seen as devoted to the illusory beauty outlined above by Ratzinger. This devotion entailed a certain understanding of the good and true. In particular, Francis set his eyes on knightly glory gained in battle, and all that would come with it.

A pivotal period in the life of Francis was his being imprisoned after a disastrous battle with the neighboring town of Perugia. This span of time, about a year, was one of great disorientation for the young Francis. The richness of this image of Francis behind bars is too much to pass over: Francis as imprisoned by both the Perugians and the deceptions of worldly gain and glory. Joseph Ratzinger remarked upon this in an address at Assisi in 2002:

It was only then, beaten, a prisoner, suffering, that [Francis] began to think of Christianity in a new way. And it was only after this experience that it became possible for him to hear and understand the voice of the Crucified One who spoke to him in the tiny St. Damian’s Church . . . Only then did he see how great was the contrast between the nudity of the Crucified One, his poverty and humiliation, and the luxury and violence that had once seemed normal to him.

Francis’s first biographer, Thomas of Celano, speaks of this period of transition and conversion when Francis, after having been released from prison—though still ill and convalescing at home—began to walk about the countryside to recover his health. Celano says that as Francis surveyed the landscape, “the beauty of the fields, the delight of the vineyards, and whatever else was beautiful to see could offer him no delight at all.”

Having been thrown into confusion and disorientation, Francis becomes reoriented before the Cross in the crumbling church of San Damiano and in the experience of mercy in his encounter with neighboring lepers. Celano speaks of Francis’s re-founded appreciation of the natural world when he says Francis “was filled with a wonderful and unspeakable love owing to his love of the Creator whenever he used to gaze upon the sun, the moon, and the stars.” As the rest of his life unfolded, Francis exhibited that knowledge brought about by experience of the divine, as described by Cabasilas above.

This is summed up well by Augustine Thompson in his recent biography of Francis. Drawing on Francis’s “Testament,” Thompson says that it is “the encounter with lepers, not the act of stripping off his clothing before the bishop, [that] would always be for Francis the core of his religious conversion . . . It was a dramatic personal reorientation.” As Thompson continues:

As Francis showed mercy to these outcasts, he came to experience God’s own gift of mercy to himself. As he cleansed the leper’s bodies, dressed their wounds, and treated them as human beings, not as refuse to be fled from in horror, his perceptions changed. What before was ugly and repulsive now caused him delight and joy, not only spiritually, but also viscerally and physically. Francis’s aesthetic sense, so central to his personality, had been transformed, even inverted. . . . [he had been] remade into a different man.

Beauty of Creation or/and the Beauty of the Cross

To think now of the beauty of creation as being in tension with the beauty of the Cross, a reconciliation can be seen in the praise and love Francis gives the God that is good. Goodness understood here as being diffusive of itself, as self-giving. Some of this can be seen in the “Parchment Given to Brother Leo,” written after Francis’s reception of the Stigmata on Mount La Verna. Among the various praises Francis addresses to God are the following: “You are good, all good, the highest good . . . you are beauty; You are meekness . . . You are all our sweetness.” In the “Praises To Be Said At All the Hours,” Francis prays, identifying God as “all good, supreme good, totally good, you Who Alone are good.”

The consonance between his love of the created order and his passionate devotion to the Crucified—to run the risk of oversimplifying the matter—arises from Francis’s vision of the good God’s diffusive, self-giving, and utterly self-emptying love, his kenosis. In the context of his Eucharistic devotion—which is surely part of this overarching image of Francis—St. Bonaventure tells us that Francis was “overcome by wonder at such loving condescension and such condescending love.” In seeing the depths and breadth and width of the divine love, Francis would say that “greatly should the love be loved of him who loved us so greatly.” Celano helps us see Francis’s love of creation as a manner of ascent to the love of the Creator. Francis’s biographer writes:

In art he praises the Artist; whatever he discovers in creatures he guides to the Creator. He rejoices in all the works of the Lord’s hands, and through their delightful display he gazes on their life-giving reason and cause. In beautiful things he discerns Beauty Itself; all good things cry out to him: “The One who made us is the Best.” Following the footprints imprinted on creatures, he follows his Beloved everywhere; out of them all he makes for himself a ladder by which he might reach the Throne.

To recall Ratzinger’s words, though, this good God hangs on the wood of the Cross, beaten and battered. How can this be beautiful? As has already been mentioned, Ratzinger holds that in the face of the Poor Man of Nazareth, “appears the genuine, extreme beauty: the beauty of love that goes ‘to the very end.’” We see that the Goodness which is the fountain-source of creation’s beauty is in turn the Incarnate God-man, the babe of the wooden crèche, he who also hangs on the tree of Cross.

In this is revealed the truth of reality at its core, its inner heart, and here is shown how one should act and live. In the work of Ratzinger, and the life of Francis, the interconnectedness and convertibility of beauty, truth, and goodness, or love, is seen. As Ratzinger suggests, the experience of beauty gives the person a new criterion of judgment, a new sight of how one’s life ought to be shaped.

There is something particularly significant to this story in the San Damiano crucifix itself. Upon it is Christ Crucified, though, interestingly, he is there with eyes open, with a slight smile on his face. His head is haloed and above it, in the uppermost portion of the cross, we see Christ ascending to the glory of Paradise. Even though blood issues from his hands, feet, and side, he is triumphal; crowned not with thorns but gold. The sufferings of the cross are framed by the glories of the Resurrection and Ascension.

In his The Beauty of the Cross, Richard Viladesau remarks, with such a cross, “the triumphal theological element prevails over historical realism: Jesus’ head is usually surrounded by a halo . . . he is portrayed iconically, alive with the divine life that would be manifest in the resurrection.” Viladesau comments further:

The smile of Christ therefore reminds us that the One who suffered on the cross is the incarnate Word. . . . despite the reality of his human suffering, in his divinity Christ remains impassible: he is inseparable from the eternal bliss of God.

It is not hard to imagine that Francis was shaped by this reality as expressed through the cross of San Damiano. The cross seen not as ugliness and woe, but the fullest expression of divine goodness, that goodness whispered of, hinted at, and pointed to, throughout the whole of the created order.

As it was, Francis’s life was imprinted by this cruciform narrative. It is from this cross that we hear Christ speaks to Francis. It is the wounds depicted on this cross that Francis himself would bear, an external, embodied sign of Francis’s conformity to the Crucified. Before this Cross, Francis sees his mission. As Ratzinger says elsewhere of the Poor Man:

When one stops to pray before a Crucifix with his glance fixed on that pierced side, he cannot but experience within himself the joy of knowing that he is loved and [having] the desire to love and to make himself an instrument of mercy and reconciliation.

In Francis’s understanding of the Passion there was a centrality to the generosity and gratuitously diffusive and life-giving self-gift of the good God. Here is the touchstone of Francis’s post-conversion aesthetic. And in looking at the specific expression of this in the San Damiano crucifix, there can be seen the utter self-emptying of the Cross, though in the broader context of divine victory, wherein Christ can smirk and ascend in glory. The Cross seen in this light reveals the beauty of God.

For Francis, to rejoice in the works of the Lord would be all-compassing, the tension between the beauty of creation and the beauty of the Cross seen as not a tension at all, but as the same glorious diffusion of the divine goodness. He could see that at the heart of the garden of the world stands the tree of the Cross.