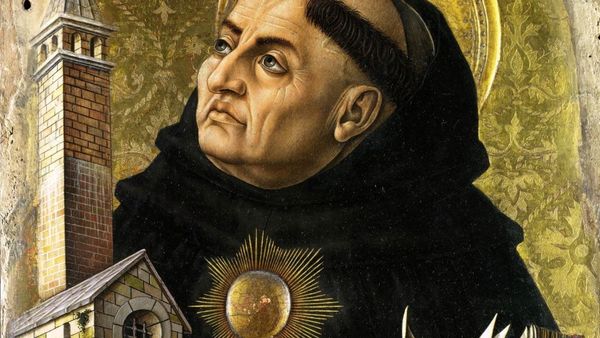

One of the great political fights in medieval Christendom affected St. Thomas Aquinas’s own studies as a youngster. A fortuitous military conflict between Emperor Frederick II and Pope Gregory IX spilling into the abbey of Monte Cassino, where Aquinas was doing his elementary studies, led to his parents sending him to the center of studies recently established at Naples. It was in Naples, at age 19, that Aquinas ran into the Dominican friars and the rest of that is history. Nevertheless, the conflict between Frederick and Gregory—a fight over the authority of the Church over the state, where Gregory was ordering Frederick to engage in a crusade under his duties to the Church, but where Frederick was unwilling and so was excommunicated repeatedly, drawing into question the duties of his subjects to an excommunicated leader—illustrated a classical political debate in Christian history that has involved the relation between the common good and jurisdiction of the State and that of the Church, since here the rights of the Church came into conflict with those of the State.

It was patently obvious to all parties that the rights of the Church are primary—how could Caesar’s rights could trump those of God? Contrary to modern fears of the state commandeering the Church for political purposes, or destroying the Church, the medieval problem was preserving the rights of the state from ecclesial overreach! The controversy was really the other way around: the question was one of whether the supernatural salvation offered in Christ, and the power of its ministers, takes away or destroys the natural rights and goods that constitute the political life of the state.

One of Aquinas’s great achievements was to differentiate the natural, the realm associated with our natural capacities and what they could discover by natural reason, from the supernatural, what we know as a result of revelation and live as a result of grace. His maxim, gratia non tollit naturam, sed perficit,[1] stands as a theological claim that the natural is perfected by the supernatural, not destroyed. Without these foundations, Aquinas proposes, one cannot understand what grace does. For many after him, Aquinas’s understanding of the harmony between grace and nature enunciated the foundations of moral and political life in a way that helped resolve those questions of Church-state relations.

There are two plausible theses about those relations that seem uncontroversial and unobjectionable. First, the structure of our political life and the state must be affected by grace; even when the State has a limited temporal competence to care for the temporal good of human beings, Christianity’s claims about freedom and justice should make a difference to our politics. Second, the structure of the Church must be perfected politics. Specifically, the natural common good of politics as involving the free consent of the governed affects how we should conceive the freedom of members of the Church and its continual reform.

I will offer a Thomistic explication of these theses which, however, will issue in what may seem a controversial conclusion: that a democratic structure to the political life—with its attendant views of fundamental human rights to conscience, free speech, and religious practice, as well as the more basic view that legitimacy in government rests upon the consent of the governed—is essential to the Christian spirit, not a corruption of Christian dogma through the influence of “modernism” or the Enlightenment. My argument for these theses involves appeal to the notion that, at the heart of Christianity’s vision of salvation is a view on which salvation is a personal, intelligent, free union with other persons.

This view got Dominicans in trouble once; the re-founder of our Order in the modern period, Fr. Henri-Dominique Lacordaire, was a famous proponent of this view, until he and his fellows were censured by the Holy See for an overenthusiastic extension of these claims to freedom of speech and religion. I will, however, argue that, rightly interpreted, Lacordaire’s claim is true of both natural and supernatural political life. That is, the Church should be democratic in important ways just as the State should be. I will conclude by reflecting—in this 800th anniversary of the death of our Holy Father Dominic—why this was not a coincidence but that the Order of Friars Preachers have exemplified, in an important way, the way that the synodal spirit of the Church should affect social structures.

*

At the core of Aquinas’s approach was a notion of the natural “common good” of society. We act together in political life for reasons that benefit everyone. In light of these facts about the common good, which are objective facts, Thomas understood political decision-making in the same way as it understands moral decision-making: a matter of discovering the truth. For politics, this is a matter of discovering the truth in matters of political or legal justice, but both ethics and politics are grounded in practical reasoning, deliberating on reasons for action that arise from objective facts about the nature of human beings and their communities.

From Thomas’s perspective, any political society, whether the state or the Church, are ordered to their common good—that good which is shared by all the members. The common good for both kinds of society, natural and supernatural, share important features. In sum, Aquinas calls the goal of ideal political life “peace.”[2] Peace is cross-categorical, because it is both the natural goal of society as well as a fruit of the Holy Spirit, a supernatural gift. This is not an equivocation, however, since peace in both cases is a special kind of harmony that results from order.

Peace goes beyond mere absence of conflict and is envisioned as a “moral unity” of all citizens in unified pursuit of the same goals. For this reason, perfect peace requires, beyond just relations between citizens, the personal virtue of each citizen. The individual’s reason, will, and other powers should be properly cooperative in pursuit of their proper end. Peace is then an objectively good state of relationships in society, as it is a state of being properly ordered (as an individual or group) toward what is truly good.[3] Thus, when appropriate relationships are achieved, peace is the natural result, so that peace is nothing more than “the tranquility of order,” a definition Aquinas gets from Augustine (De Civ. Dei xix, 13).[4]

The purpose of society is to achieve a uniquely social good founded upon relationships.[5] These goods can only be achieved in cultural activity and political life, and thus serve as the reason for the existence of the State.[6] Aquinas’s common good is a “relational” good, not abstract rights and obligations. However, the order of justice is insufficient to attain perfect peace if all we mean is legal justice:

Peace is the “work of justice” indirectly, in so far as justice removes the obstacles to peace: but it is the work of charity directly, since charity, according to its very nature, causes peace. For love is “a unitive force" as Dionysius says (Div. Nom. iv): and peace is the union of the appetite's inclinations.[7]

In other words, justice is a necessary but insufficient condition even for civil peace. Right relations between people only persist and occur in the right way if they are based on having the right reasons. Those right reasons, Aquinas alleges, even at the civil level, involve friendship. Friendship is not the sort of thing that can be forced.

For if one man concord with another, not of his own accord, but through being forced, as it were, by the fear of some evil that besets him, such concord is not really peace, because the order of each concordant is not observed, but is disturbed by some fear-inspiring cause.[8]

All virtue is a kind of harmony within the human will,[9] and love produces appropriate order within the will of individuals as well as between them, as it directs all of their relations to appropriate ends.[10] Love is thus required to properly order societal relationships appropriately and harmoniously so that societal peace, while requiring justice as a necessary condition, can only result from love among citizens.[11] Justice is then only a necessary condition for societal peace, whereas charity, properly conceived, is necessary and sufficient for peace, since love of God includes proper observance of justice and love of neighbor.

*

The ordered harmony in any society, that common good at which it aims, is an intelligent friendship among the citizens. Aquinas’s account of law—“an ordinance of reason for the common good, made by him who has care of the community, and promulgated”[12]—captures this notion that society is ordered not by mere arbitrary use of power to quell conflicts, and that societies are not merely judged as legitimate or moral by how well they achieve efficiently the public goods that we all rightly care about (e.g., water, clothing, economic growth, international prestige), but by whether those societies achieve this kind of intelligent friendship based on free consent. Aquinas thus states, right at the beginning of the treatise on law, that law is not defined in terms of its ability to invoke violence or coercion against those who violate it. Instead, law is a rule and measures of acts that is directed toward the reason of citizens and only, accidentally and in the situation of sin, to punishment and coercive force.

Freedom conceived as merely negative does not benefit society. The common good involves harmony, and harmony must be based on truth, not merely freedom from coercion. If use of coercive force is possible for actions, it certainly must be legitimate to coerce (one might think) people into believing the right things. There is, instead, some might argue, no fundamental right to free speech or conscience or religion when these do not promote the true good of the people. For example, instability results from permitting widespread questioning of the legitimacy of the government or differing views of what is moral. The maxim that an unjust law is no law cannot be correct in a flat-footed sense—who gets to decide if the law is unjust? Society would undermine itself if anyone could question their leaders and obey the laws only when they find them reasonable or moral; it is naïve in the extreme to think that people will just freely follow the law. If state power, by itself, cannot coerce people into believing the right things, this translates into a right to hold whatever moral or political views we want, and that looks two steps away from moral relativism.

In good Thomistic fashion, I distinguish: a view on which people have fundamental rights to free speech or conscience, resting on the view that state coercion can only be employed justly when that coercion is publicly reasonable, is not the same as moral relativism. These rights concern what we can do to one another, not our duties to God or even the state. A moral duty to seek the truth is perfectly compatible with the claim that nobody on earth can rightfully or justly force you to accept the truth. In fact, for the subsequent Catholic tradition shaped by Aquinas, these rights flow from our duties to the truth and the common good of society.

The view that any government use of force is justified as long as, by it, we bring people by hook or by crook to do what’s really good for them, is based in an error on the nature of the common good, and ultimately, in the nature of love. The objector has misconceived of the end of human life and the common good itself. The common good is not merely efficient achievement of public goods or enforcement of the laws. The common good of all is peace, a harmony that is based on free consent in the reasoned acceptance of the truth, not merely the harmony of forced concord and non-conflict.

Love too is not merely desiring the good of another, but also a desire for union with the other in that desire. The theological version of these misunderstandings of the nature of true love ends up in heresy: universalism, the belief that God would be cruel and unloving if he did not save everyone by necessitating their choices. While God’s grace goes before us, and is required to move us to act rightly, God never acts violently on the human will, not even to save people “despite themselves” from the eternal consequences of their choices. False understandings of freedom and love fail to appreciate, in society as well as in beatitude, that a true lover respects the dignity and choices of the beloved, even in many cases when the beloved fails to live up to their own good. Sanctifying grace, union with God, is a perfection of the rational nature of human beings; “perfectio naturae rationalis creatae,”[13] and grace can only exist when God’s offer of salvation is accepted reasonably, freely.

Christian theology developed the ideal that, because our relationship with God by grace is free, no power under heaven can compel an act of faith and acceptance of baptism. The Church affirmed this right to religious freedom at Vatican II in Dignitatis Humanae. Dignitatis Humanae 3 offers a Thomistic justification for a right to freedom of conscience:

The highest norm of human life is the divine law-eternal, objective and universal-whereby God orders, directs and governs the entire universe and all the ways of the human community by a plan conceived in wisdom and love. Man has been made by God to participate in this law, with the result that, under the gentle disposition of divine Providence, he can come to perceive ever more fully the truth that is unchanging. Wherefore every man has the duty, and therefore the right, to seek the truth in matters religious in order that he may with prudence form for himself right and true judgments of conscience, under use of all suitable means.

It continues:

Truth, however, is to be sought after in a manner proper to the dignity of the human person and his social nature. The inquiry is to be free, carried on with the aid of teaching or instruction, communication and dialogue, in the course of which men explain to one another the truth they have discovered, or think they have discovered, in order thus to assist one another in the quest for truth.

The fact that human dignity demands respect for the freedom of others’ conscience has distinct effects on how we conceive of justice in society. The later Baroque Thomists of Salamanca nurtured from Aquinas’s principles the initial blossoming of a theory of natural rights and international law. The central implication I wish to highlight that follows from Aquinas’s view of natural law and the source of political authority, enshrined in recent magisterial teaching, is that, “the subject of political authority is the people considered in its entirety as those who have sovereignty” (Catechism of the Social Doctrine of the Church, §395).

*

Despite exaggerated ultramontanist tendencies, the Church was never intended to be a monarchy of the clerics, let alone the papacy, where one person or a small group of elites lord it over all without anything beyond merely moral limitations on the exercise of their power. With an attendant emphasis on the fundamental equality and dignity of all, the Church from its earliest days engaged in a specific and unique form of government that characterizes its unique character: councils or synods. Syn-odos (to walk a path together) refers to Christians as followers of the unique Way that is Christ; since we are all fellow believers, Church governance and its decisions touch us all. Quod omnes tangit ab omnibus approbari debet—what touches all ought to be approved by all.

In the Church, it is true in one sense that the authority of the Church derives from a divine mandate rather than the natural law and consent of the governed. The Church has from its inception as a visible body founded by Christ possessed equally visible leadership: officials, teachers, pastors, notably bishops and presbyters, and the Catholic Church has upheld the notion that one cannot give oneself a divine mission to preach or to govern by its doctrine of Apostolic Succession—one can only preach if one has been sent by the Church and its legitimately instituted bishops who trace their authority to that of Christ.

The Church is a product of grace, not of our personal free merit, not created by the ingenuity of human beings or their consent. The authority that the Church claims for its teaching infallibly derive from this divine mission, not from some inherent inerrancy in its leaders or members; that divine mission leaves members of the Church to their own fallibility and it is in spite of our weaknesses that God maintains the Church as a pillar and bulwark of the truth, never to corporately teach religious or moral error.

Nevertheless, in a deeper sense, the authority of the Church over its members is grounded in the freedom of baptism by which each member joins the Church and promises to uphold its mission in their baptismal promises. The Church’s jurisdiction is not over Jews or Muslims, but over those who consent to its ministers and laws by freely accepting baptism. Just as God does not force our salvation, the means of salvation he appointed, the Church, outside of which nobody can be saved, requires us to give our free consent to become a member. The catechumenate expresses our desire for the Christian to offer themselves to God at the Easter Vigil freely after a period of instruction so as to make a well-thought-out, voluntary decision.

The limits of political authority, given by the natural law, have ecclesiological implications. Cardinal Cajetan once argued that even the role of the pope in the Church is limited in many ways:

The authority of the church-community over the pope by natural law is established by the consideration that the community is complete and free and has the functions of providing itself with a prince, of protecting itself against him when he uses his power harmfully.[14]

The subsequent development of the doctrine of papal primacy, from Vatican I to Vatican II, noted that the constitution of the Church limits the authority of the Pope. To say that the Church is constitutionally synodal thus implies important truths about ecclesial governance and the proper conditions for just use of authority within the Church, namely, that it relies on consent of the governed. In fact, Nicholas of Cusa once explicitly argued that, if natural law bases political authority on the consent of the governed, so too does the Church’s constitution:

Every constitution is rooted in natural law and cannot be valid if it contradicts it . . . Since all are free by nature, all government, whether by written law or a prince, is based solely on the agreement and consent of the subject. For if by nature men are equally powerful and free, true and ordered power in the hands of one can be established only by the election and consent of the others, just as law also is established by consent . . . It is clear, therefore, that the binding validity of all constitutions is based on tacit or express agreement and consent.[15]

In the ancient Church, bishops represented their diocese in a much more intimately political sense because, even though laity did not typically have voting rights in the councils or synods, the laity did elect their bishops to their offices—bishops were then naturally seen as elected representatives of the Christian people, illustrating visibly that the Church is governed not merely by autocratic leaders, but by leaders who rule with their subjects, as fellows on the same path. Synodal governance is not a license to the view that our doctrine is decided democratically—all of that is ridiculous, as it would undermine the fact that doctrine can only be known by revelation from God—but rather that, even in decisions of dogmatic force, the ministers of the Church have an obligation to decide all of their most important questions for the life of the Church synodally, even consulting the lay faithful in matters of doctrine as necessary or reasonable (as St. John Henry Newman famously defended).[16]

If the Church felt itself bound to decide its greatest doctrinal questions in councils, it would be absurd of us to think that disciplinary questions about how to order the life of the Church in our local diocese should not also be decided in a conciliar way. The premise of synods is that we have a corporate duty to seek the truth together and that this duty cannot be fulfilled by each member without their rights and freedom for participation in that process being respected. This is what inspired St. John Chrysostom to offer the image of the Church as “the assembly convoked to give God thanks and glory like a choir, a harmonic reality which holds everything together (σύστημα), since, by their reciprocal and ordered relations, those who compose it converge in αγάπη and όμονοία (common mind).” (CDF, Synodality in the Life and Mission of the Church, §3). Autocratic decision-making by bishops who are not accountable to the faithful and can even act contrary to the rights of those faithful, we might even say, are acting contrary to the unwritten constitution of the Church.

*

An early twentieth century scholar claimed “The institutions and the mentality which constitute modern democracy are a heritage from medieval churchmen . . . But if democratic government owes its inception to the Councils, it owes much of its perfection to the Friars.”[17] Characteristics of the Dominican Order’s constitution seem to many to have affected early European democratic institutions: modern constitutionalism with a clear distinction between constitutional and legislative enactments, all authority vested in representatives elected by local communities, practically complete self-determination with each level electing its leadership, and federalism combined with autonomy.[18]

Whereas scholars have speculated that democratic governance was connected to the rise of our Dominican Order, recent study seems to provide concrete statistical evidence that this was the case. Jonathan Doucette argues that the Dominican Order functioned in medieval Europe as an engine for regime change from autocratic to representative city government among medieval European cities. Doucette argues that the Dominican Order spread its ideals of governance by forming its men intellectually in the theological tradition, with a solid foundation in the ideas and skills that allowed friars to speak to the secular world, and their friars were engaged in working alongside the elites of society, not merely in isolation among Catholic institutions or private affairs of the Church. Members of the Order taught in universities and secondary schools, and helped perform tasks for the administration of the city, friars functioning essentially as consultants and priories as think tanks for policy.

While cities were often ruled by “a small number of wealth families, a bishop, or a prince,” the Order provided a working, demonstrably stable model of democratic representation that could be imitated by smaller local governmental institutions, one in which different political viewpoints were represented by the friars and where opposition politics were worked out together in a democratic context by competent, university men who were representatives of the local communities of friars. Doucette found that, by comparison with other cities (on one metric), “Dominican cities had a 40%-point chance of transitioning—more than twice as high.” He also tested it against the Franciscan Order (apologies to brothers from another father!) and found no discernible relationship between that Order and representative government. [19]

The spread of these ideals by the Dominican Order has lessons for us Christians today. The Order was a sign of the freedom of Christ in the midst of an autocratic world, so too in the midst of a medieval Church that had grown too comfortable with power and wealth. The friars’ evangelical poverty, zeal for study and preaching, and democratic spirit affected the Church. They exemplified that rational persuasion, consultation, representation, and respect of freedoms and rights could produce good governance and peace, as well as conversions of nonbelievers, without need to resort to coercion and force. What we preached was that living in and for the truth, under grace, brought true freedom, and the friars exemplified what they preached.

The claim it was necessary to compel people to accept or continue to practice the Catholic faith was shown to be a diabolical lie, just as today the belief that Christians must take advantage of government power to implement “muscular” cultural Christianity, legitimizing systematic violation of the rights of religious minorities, can only be diabolical. These visions implicitly rely distorted notions of salvation which deny the freedom of grace. The synodal spirit of the Church is essential to its mission, but also essential to the peace and justice of the societies in which we live, and it is our baptismal duty to exemplify and spread that fragrance of Christian freedom wherever we go. "For freedom Christ has set us free" (Gal 5:1).

[1] Summa Theologiae [ST] I, q. 1, a. 8, ad. 2.

[2] C.f., Thomas Aquinas, De Regno, c. 3, n. 17.

[3] It should also be noted that the ‘order of divine justice’ is an order immanent to created things, so that they have their own natural principles of action. Charity is thus the fulfillment of these natural principles. C.f., ST I-II, q. 93, a. 5, resp.

[4] ST II-II, q. 29, a. 1, ad. 1.

[5] Charles de Koninck, The Primacy of the Common Good, in The Writings of Charles de Koninck, vol. 2, ed. and trans. Ralph McInerny (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1999). Esp. 75.

[6] Jacques Maritain, The Person and the Common Good, trans. J. Fitzgerald (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press. 1966), 49-53.

[7] ST II-II, q. 29, a. 3, ad. 3.

[8] ST II-II, q. 29, a. 1, ad. 1.

[9] Summa Contra Gentiles IIIb, c. 139, 15.

[10] ST II-II q. 45 a. 6 ad 3 [Ultimum autem est, sicut finis, quod omnia ad debitum ordinem redigantur, quod pertinet ad rationem pacis.] “The ultimate is that by which, as end, all is appropriately ordered, which pertains to the definition of ‘peace’”

[11] ST II-II, q. 39, a. 3, ad. 3; q. 29, a. 4, resp. […non est alia virtus cuius pax sit proprius actus nisi caritas.]

[14] De auctoritate papas et concilii, ii., 1----Opuscula (Venice, 1580), i., p. 16d. [Trans. Rahily, cited below.]

[15] De concordantia catholica, ii., 14 (Opera, Basel, 1565, p. 730). [Trans. Rahily, cited below.]

[16] John Henry Newman, “On Consulting the Faithful in Matters of Doctrine,” in The Rambler, July 1859.

[17] Alfred Rahily, “The Catholic Origin of Democracy,” Studies Vol. 8, No. 29 (Mar. 1919): 8, 10.

[18] Ibid., 11.

[19] Jonathan Doucette, “The Diffusion of Urban Medieval Representation: The Dominican Order as an Engine of Regime Change,” in Perspectives on Politics, Vol. 19, Is. 3 (Sept. 2021): 723-738. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592720002121