SPOILER ALERT: BREAKING BAD AND BETTER CALL SAUL SPOILERS BELOW!

Pilot: Deceiving Ourselves and Others

In his 2010 memoir, Hannah’s Child, Stanley Hauerwas notes that we humans “are subtle creatures capable of infinite modes of self-deception.”[1] Some thirty-five years earlier, Hauerwas and Fr. David Burrell asserted that “our ability to . . . live authentically depends on our capacity to avoid self-deception,” something that we cannot do without “developing the skills required to articulate the shape of our individual and social engagements.”[2] Our failure to develop these skills is not, Burrell and Hauerwas suggest, “a wholesale charge of hypocrisy.” Rather, “self-deception remains more subtle.”[3]

Self-deception is not an exercise in deliberate dishonesty, whether before ourselves or others. It certainly may be the case that we deliberately construct false histories about ourselves, and these histories may eventually lead to self-deception. But in these instances, we are not deceiving ourselves: we know we are lying. The self-deception that Burrell and Hauerwas describe, and which is more prevalent in the TV series, is different from deliberate prevarication. “Self-deception must stem from a purpose strong enough that our position cannot be interpreted as a sham,” they explain. That purpose often takes the form of ignoring, or attempting to ignore, indications that are contrary to our developing story of self-deception. Moreover, self-deception is not an isolated exercise of obfuscation, misdirection, or feint. Rather, our tendencies toward self-deception are rooted in larger stories by which we attempt to construct accounts of ourselves that support contradictory identities. Self-deception, like any virtue or vice, is a skill learned through the repetition of habits and practices, accompanied by some intentional purposes or posited ends. As Burrell and Hauerwas put it,

A state of self-deception cannot issue from a single decision, . . . but reverts to a policy not to spell out certain activities in which the agent is involved. Moreover, once such a policy has been adopted, there is ever more reason to continue it, so that a process of self-deception has been initiated [emphasis added]. Our overall posture of sincerity demands that we make this particular policy consistent with the whole range of our engagements. In this way, a specific policy leads to a pervasive condition called self-deception. Curiously enough, it is our prevailing desire to be consistent which escalates a policy into an enveloping condition.

…

We may even feel that the commitments we have made require us to keep up an ongoing policy of avoidance. We may feel compelled to maintain our web of illusion because others have been drawn into it.[4]

Both Walter White and James McGill engage in processes that lead to policies that escalate into enveloping conditions of self-deception.

Walter and Jimmy are not the only characters in the series who engage in forms of self-deception similar to that described above. At various times, Walter Jr., Jesse Pinkman, Kim Wexler, Hank Schrader, and Marie Schrader also practice these policies. Some of these exercises in self-deception are benign in their origins. Sometimes they are temporary mechanisms of psychological or emotional self-protection. For example, Walter, Jr. invents an identity for himself to cope with the confusing tension of the early separation of Walter and Skylar. Marie invents various identities to protect herself from the stress of her alienation from Hank after he is shot. But even these kinds of exercises in self-deception, while rooted in natural tendencies of self-preservation, may lead to unanticipated harms. As Burrell and Hauerwas put it, “Our protective deceits become destructive when they begin to serve our need to shape a world consistent with our illusions.”[5] Thus, even these less obviously tendentious forms of self-deception are fraught with danger, even when they are confronted. “The very same imaginative and intellectual skills which lead us to discriminate falsity from truth also empower us to create those webs of illusion that lend plausibility to our original deceptive policy,” explain Burrell and Hauerwas.[6]

Their point can be demonstrated by the way that various characters’ names are given, taken, invented, changed, asserted, and repudiated in Breaking Bad and Better Call Saul. In the various uses of names and naming, Gilligan and the other showrunners carry on a sustained illustration of the varieties of ways that we engage in self-deception. This occurs across a spectrum, from benign attempts for self-protection to malicious and vicious criminal intentions. Regardless of where various examples of naming-as-deception fall on this continuum, they are all attempts by the characters to assert control over the contingencies that otherwise try to name them. The uses of names in both series variously work to overcome these contingencies or surrender to them. In either case (asserting or surrendering control), exercises in naming are attempts to express agency and identity, whether for good or ill. As Burrell and Hauerwas put it, we need to “establish some sense of identity and unity . . . to give coherence to the multifariousness of our activities. Identity is the power to spell out, to avow, a particular aspect of our history as uniquely ours and as constitutive of the self.”[7] In Breaking Bad and Better Call Saul, this is done through the practice of characters giving themselves names.

Episode 2: “What’s Your Name?”

My title is taken from one of the more famous scenes from Breaking Bad, so pivotal in fact, that the entire episode is named for the line.[8] That episode (season 5, episode 7), comes very late in the Breaking Bad saga. But we are introduced to the name in episode 6 of season 1, after Jesse Pinkman’s failed attempt to make a distribution deal with Tuco Salamanca, in which Jesse not only loses a pound of the product but is beaten nearly to death (for the first time). Walter, having shaved his head and dressed in black (in contrast to his usual variations on beige and taupe), confronts the psychotic drug lord, intent on making a deal to distribute the product. Identifying himself only as “Heisenberg,” Walter enters the underworld of methamphetamine production and distribution.[9]

This scene marks the beginning of the transition of Walter White from an underpaid, mild-mannered high school chemistry teacher and part-time car wash attendant (who incidentally manufactures methamphetamine to pay his medical bills), to a would-be drug kingpin. In the pilot episode, Walter reprimands a student for being a distraction in class. After school at his second job, Walter is humiliated when he is forced to scrub the tires of that very student’s expensive sports car, to the delight of the student and his girlfriend, who gushes about it on her cell phone. That very evening, Walter fades into the background of his own fiftieth birthday party, while his testosterone-fueled brother-in-law—DEA agent Hank Schrader—takes center stage, boasting of a large drug bust featured on the evening news, and intimating that Walter is not a “real man.”

But here in Tuco’s headquarters, in the midst of the very villains whose crimes Schrader is supposedly thwarting, Walter is transformed into a new persona. As he walks triumphantly through the debris of Tuco’s destroyed headquarters, Walter initiates a policy of self-deception that “escalates . . . into an enveloping condition,” to return to Burrell and Hauerwas’s language.[10] But, at least at this point in the story, calling himself Heisenberg is not itself the act of self-deception. He knows he is not the new Tuco and, at least at this point, has no aspiration to be. Walter is not lying to himself that he is Heisenberg. He knows he is not. Neither is he lying to himself that he is just Walter White, an underpaid chemistry teacher. Nor, finally, is he lying to himself that he can maintain the two identities. On the contrary, as the story unfolds, we learn that Walter believes that he can maintain the two identities; and this is the root of his self-deception.

Walter’s double identity is not a lie, because he believes it can be maintained. His moral pathology goes much deeper, and is more intractable, than mere lying. To put it in Burrell and Hauerwas’s words, “We do not just play at self-deception. For we often come to realize how deceived we have been, yet quite unsuspectingly all the while.”[11] Rather, Walter’s self-deception consists in thinking that he will be able to continue manufacturing meth as Heisenberg, while at the same continuing as Walter White, a mild-mannered high school chemistry teacher. The act of self-deception is not calling himself Heisenberg, but rather in thinking that can be both Heisenberg and Walter. And deceiving himself in this way, Walter is trying to gain control over a number of contingencies (illness, penury, emasculation) that threaten his moral agency. This is the path that Walter enters in this episode, “A Crazy Handful of Nothin’.”

The two identities are illustrated in three early scenes. The first is when Walter leaves Tuco’s headquarters in full bad-ass Heisenberg mode, having blown the place up and forcing Tuco to accede to his payment demands.[12] In the next scene, Hank Schrader, not knowing who is behind a new powerful form of methamphetamine on the streets, finishes a team briefing at his DEA office, declaring that there is a new kingpin in Albuquerque. As he says this, the scene flashes to a pudgy Walter White brushing his teeth in his underwear in the bathroom of his shabby house.[13] The difficulty of maintaining the two identities is illustrated in the scene after Tuco has kidnapped Walter and Jesse, and taken them to his uncle’s shack in the desert. After Tuco demands Walter’s wallet and discovers that his name is Walter Hartwell White, Walter sheepishly says that Heisenberg is a pseudonym; a sort of business name.[14]

Walter’s complex efforts at self-deception ignite a tragic chain of events. A state of self-deception “cannot issue from a single decision,” Burrell and Hauerwas maintain, “but represents a policy not to spell out certain activities in which the agent is involved.”[15] Most immediately, of course, Walter must negotiate his own daily life as a chemistry teacher by day and a meth cook by night and weekend. This involves the stress of keeping his stories straight while trying to invent new ones. His long, mysterious absences begin to cause a strain on his marriage and emotional stress on his son, Walter, Jr. Beginning to fit the pieces together, Skylar forces Walter to move out of their house at the beginning of season 3, deducing that he is a drug dealer. In the wake of this, and returning to my theme, Walter Jr. tries to cope with these stresses by giving himself an invented name, “Flynn,” thus distancing himself from his patronymic.[16]

Eventually, among other casualties, Hank is nearly killed and permanently injured when he is shot by Tuco’s cousins, Leonel and Marco Salamanca. After this, Hank expresses resentment and hostility toward Marie as he becomes wholly dependent upon her, even for urinating and moving his bowels. Already psychologically fragile and predisposed to shoplifting, Marie Schrader descends further into a spiral of deception and petty theft. Jesse’s girlfriend, Jane, dies of a drug overdose that Walter could have prevented. This leads to Jane’s father Donald, a flyover air-traffic controller, causing the collision of two passenger planes over Albuquerque. Despondent over his error, Donald eventually takes his own life. And, of course, Walter’s activities lead to the deaths of his brother-in-law, Hank Schrader and Hank’s partner, Steve Gomez. Our “protective deceits,” in the words of Burrell and Hauerwas, “become destructive when they begin to serve our need to shape a world consistent with or illusions.”[17]

All of these events occur while Walter labors under the self-deception that he can be both Walter White and Heisenberg; that is to say, while he attempts to “maintain [a] web of illusion because [he has] drawn others into it.”[18] The narrative arc eventually leads to Walter/Heisenberg’s winning of his epic “Face Off,” to use the double-meaning title of the final episode of season 4, in which Walter succeeds in killing Gustavo Fring. This marks a sharp turning point in Walter White’s self-deception. Having been fired from his teaching job and revealed to Skylar that he manufactures meth, Walter is no longer maintaining the self-deception of the dual lives. After he kills Gus, Walter tells himself that he can carry on a criminal enterprise in the same way that one leads a conventional business. He moves from self-deception to delusion, along with the hubris that comes with it. And as he does, he descends into a deeper, darker path.

Episode 3: “Say My Name”

After Fring’s death, Walter, Jesse, and Mike Ermentraut form a partnership to begin manufacturing again. As Walter becomes more obsessed with accumulating money, and thus more difficult to work with, Mike secretly negotiates an agreement with a competitor to sell the methylamine they had stolen from Madrigal. Walter refuses to go along with the deal, arguing that they can make many times the $15 million price of the precursor by turning it into meth. In the episode, “Buyout,” Jesse goes to Walter’s house to try to convince him to go along with Mike’s deal. Like an emperor on his shabby cloth-upholstered thrown in his drab and dreary living room, Walter tells Jesse why he will not agree to sell the methylamine. “I’m in the empire business,” Walter declares.[19]

Rather than to sell the methylamine, Walter devises a scheme to continue manufacturing meth, enlisting his competitor as a distributor for a percentage of the profit. This leads to one of the truly iconic scenes in the entire franchise, in which Walter demands of a rival meth manufacturer, “Say my name.”[20] In full Heisenberg mode, Walter now believes that he is invincible. Having slain the old emperor, he presumes to take his place, simultaneously eliminating a competitor, and building a new empire. And, as Hank and the DEA close in on Mike, the new emperor commences to eliminate anyone who can lead the investigation to him. This includes killing Mike and all ten of “Mike’s guys” in three different prisons. This occurs in season five, episode eight, “Gliding All Over,” taken from poem 271 of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, the very book that becomes Walter’s undoing.

I continue to puzzle over why Walter did not dispose of his copy of Leaves of Grass, a gift from his erstwhile lab assistant, Gale Boetticher. It seems to be inconsistent with the care that Walter otherwise took in covering up his schemes, exemplified, for example, in disposing of the Lily of the Valley plant used to poison Brock, the son of Jesse’s girlfriend, Andrea. The best explanation is that Walter had become convinced of his own invincibility. Having killed Fring and eliminated all the possible living links to his criminal activity, Walter seems to have concluded that he could not be beaten. He truly was invincible. Thus, after he retires from the business, he casually lays the book out in the open (albeit in his bathroom), for anyone to stumble upon. And, of course, that is precisely what happens, when Hank uses the bathroom in the midst of a cookout, and casually opens the book to the dedication page, linking Walter to Boetticher and setting Hank on the trail that would lead to the tragic ending of Breaking Bad.

Episode 4: “Who May I Say is Calling?”

Certainly, a great deal of tragedy occurs between the discovery of Leaves of Grass and the end of the series. Before Walter flees to New Hampshire with a new name (Mr. Landry), he leaves death and mayhem in his wake. Nor is the bloodshed over. When Walter returns from New Hampshire in the epic final episode, “Felina,” he comes seeking (and finding) vengeance. But in the closed fictional anti-hero world of this installment of Gilligan’s Archipelago, can any redemption be found? I am not sure of the answer to that question. But if the answer is in the affirmative, it surely must be related to Walter’s return not just to Albuquerque, but to the use of his own name.

From New Hampshire, Walter calls Walter Jr. from the payphone in a bar to tell Junior that he is sending a box of cash to one of Junior’s friends. Walter Jr. dramatically rejects the gesture, blaming Walter for Hank’s death, and wishing death upon Walter himself before slamming down the phone. Walter had told himself and Skylar that everything he did, he did for his family. Now, the one member of his family to whom he could reach out, and for whom Walter wanted to provide, summarily rejected that help. What was left, but to surrender? To admit that the ruse was over and to put closure on the entire sordid career of Heisenberg?

Thus, Walter makes another call from the same payphone, this one to the Albuquerque office of the DEA. After identifying himself as Walter White, he lets the phone receiver hang by its cable and walks back to the bar to order a drink.[21] His intention is for the call to be traced and for the police to arrive and arrest him. He has surrendered both his identity as Heisenberg and the delusion that he could take care of his family with the blood money from his methamphetamine empire. Walter Jr. seems to have convinced Walter that he could not be the outlaw Heisenberg and the family provider Walter White. It looks as though he is ready to become transparent. He seems finally to have dropped all efforts at self-deception, is prepared to confess his crimes, and to face the consequences. Perhaps, we might reasonably surmise, he is even ready to seek redemption.

But when Walter walks back to the bar to have a drink and wait for the police to arrive, the bartender, surfing channels, chances upon an episode of the Charlie Rose show, in which Gretchen and Elliot Schwartz, respectively Walter’s former business partner and lover, were being interviewed about Walter himself.[22] As Walter watches the interview two distinct lines of resentment are aroused in him, revealing that Walter does not yet seem ready for redemption.

First, it revives his long-held grudges against Gretchen and Elliot both for having sold his interest in their company, Gray Matter, and the end of Walter’s love affair with Gretchen. This thread has run through Walter’s entire criminal career, being a major reason that he refused any financial aid from the Schwartzes. Second, Walter’s resentment is aroused by the news that his proprietary blue methamphetamine is back in circulation. Someone was profiting from his brilliant invention. And, of course, he knows who it is. The same people responsible for the theft of his fortune were continuing to profit from the source of that fortune, Walter’s own intellectual property. And it is reasonable to surmise that he suspects Jesse as the cook. This suggests a variation on the second resentment: Jack Welker was supposed to have killed Jesse as part of his dark bargain before the shootout in the desert in episode 13 of season 5. All of this revives Walter’s resentment at all the wrongs that had been committed against him. And so, on the very brink of accountability, Walter hardens his heart and sets his face like flint to get his revenge in one last violent thrust against his sources of resentment.

Episode 5: “I did it for me.”

Among the more interesting debates about Breaking Bad is whether any comedic redemption can be found in it, or whether it is ultimately tragedy all the way down. In the past, I have been of the opinion that there is no redemption in the show. The subtitle of this article is “Self-Deception, Transparency, and Redemption in Breaking Bad and Better Call Saul.” I have tried to account for Walter’s self-deception. And he seemed to be on the brink of transparency when he called the DEA office from the bar in New Hampshire. But, as noted above, that impulse lasted as long as it took for Walter to walk back to the bar for a Dimple Pinch, neat. And the cold-blooded planning for the murders of Lydia and the Welkers suggests that Walter is never redeemed.

It might be pointed out in response that Walter rescues Jesse from the Welkers. But that is surely incidental to his purpose of killing the entire Nazi clan. Jesse could just as easily have been killed as anyone else in their headquarters. Moreover, the last time they had seen one another, Walter had fingered Jesse to Jack Welker for execution. And Walter was furious with Jack Welker for not only not killing Jesse, but “making him his partner,” as he accuses Jack in the last scene. Of course, Jesse did survive the carnage, and Walter let him flee. But I am not convinced that we can really find Walter’s redemption in that scene. Walter did not return to ABQ to rescue Jesse. And perhaps he even intended to kill him when he left New Hampshire.

Another pivotal scene in “Felina,” however, analyzed in the light of Burrell and Hauerwas’s essay, suggests a sliver of a possibility of something like redemption for Walter. After Skyler learned of Walter’s side-hustle, Walter had repeatedly told Skylar variations of “everything I have done, I have done for the family.” This is the context of Walter’s last encounter with Skylar in the run-down, claustrophobic kitchen of her dingy apartment. Skylar interrupts Walter from saying, as she thinks he will, that he committed his crimes for the family. In response, Walter says, “I did it for me. I liked it. I was good at it. And, I was really . . . I was alive.”[23] Skylar’s face reflects both her surprise at Walter’s confession and her belief that he was telling the truth. But this is not to say that Walter was lying when he had earlier insisted that everything he did, he did for his family. Self-deception is not lying; the self-deceiver believes the deceit.

Walter’s confession in this scene might be seen as a purging of the counsel given him by Gus Fring in the episode, “Más” (season 3, episode 4). There, Gus is trying to convince Walter to work for him in his new lab. But Walter resists, saying that he has “made a series of very bad decisions, and . . . cannot make another one.” Gus asks, “Why did you make these decisions?”, to which Walter replies, “for the good of my family.” Gus then responds, “Then they weren’t bad decisions. What does a man do, Walter? A man provides for his family.” Walter protests that his decisions have cost him his family. To which Gus responds, “A man provides. And he does it even when it is not appreciated, or respected, or even loved. He bears up and he does it. Because he’s a man.”[24] Walter eventually convinced himself that Gus’s speech was morally true, and he deceives himself that this is the motivation for the “series of very bad decisions” that he makes afterward.

If redemption can only follow confession, and transparency is a necessary part of confession, it is arguable that Walter expresses an impulse toward redemption in this confession to Skylar. By no means, of course, am I suggesting that Walter is a saint, even within the closed moral world of the anti-hero genre. Even after his confession, Walter exacts violent revenge against Lydia Rodart-Quayle and Jack Welker’s gang. Nonetheless, Walter seems to have overcome his self-deception, a necessary if not sufficient condition of his redemption.

Epilogue: “The Name’s McGill. I’m James McGill”

If transparency and confession are necessary elements of redemption, Jimmy McGill’s redemption is less uncertain than Walter White’s. It is difficult to know when Jimmy is lying and when he is practicing self-deception. And, as I noted at the outset, the habits and practices associated with lying can lead to self-deception. But we can, I think, identify both Jimmy’s self-deception and his redemption in two classic BCS scenes.

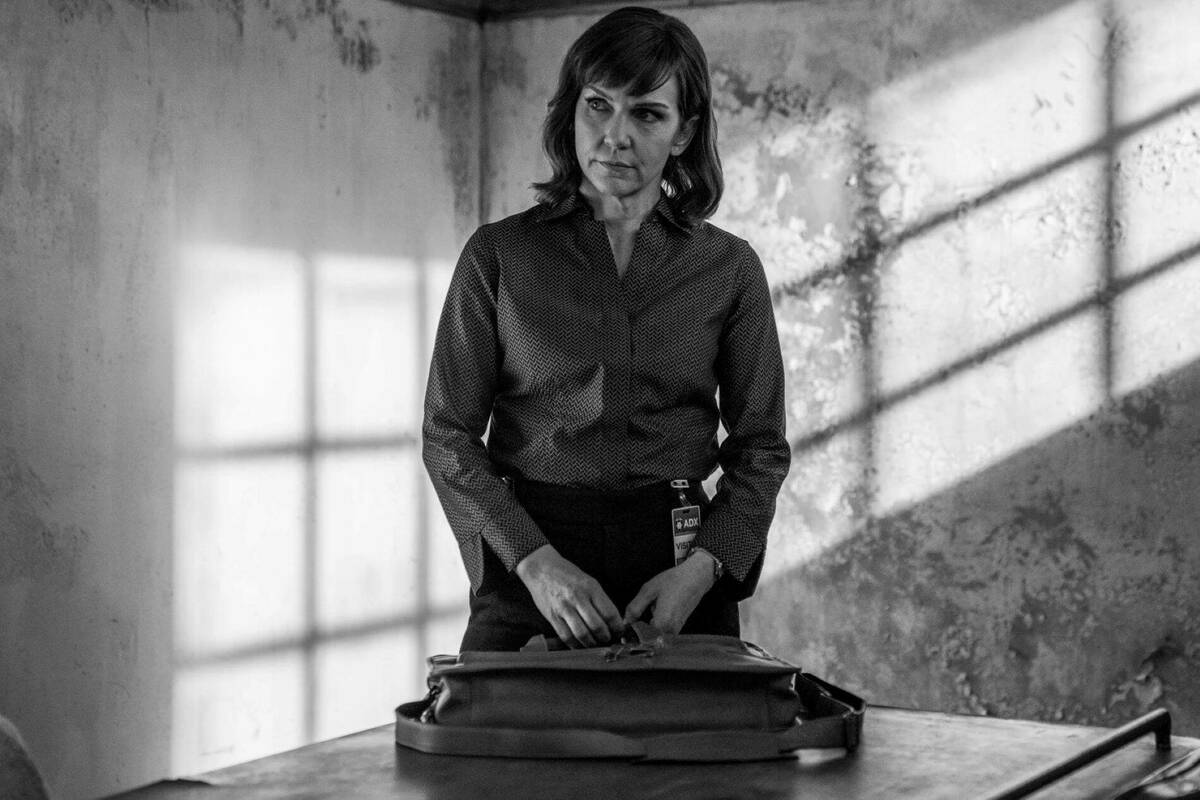

The first scene is when Jimmy wins his appeal to be reinstated to the New Mexico bar. He goes to the hearing with the intention of reading a letter that his brother, Chuck, had written to him, instead of trying to use his own words to convince the panel that he should be reinstated. Jimmy thinks that the words of his highly-regarded brother would carry more weight than his own. But in the midst of the hearing, he changes his mind. Folding the letter, he confesses, “I was gonna try to move you all with my brother’s eloquent words. You know, pull on your heart strings. But it’s not right. This letter’s between me and him. And it should stay that way.” He then seems to make a heartfelt, if somewhat ineloquent, confession of the tension with his brother and his own failures, both as a person and attorney. In the scene, he does not even throw himself on the proverbial mercy of the court. Rather, he makes his “confession,” and tells the panel they must do what they must do. Kim Wexler, sitting behind Jimmy in the hearing room, wipes away tears as she listens to Jimmy speak from the heart (or so she thinks). She, like the panel, believed the sincerity of Jimmy’s monologue.

But the motto of Jimmy’s life could have been, “Sincerity: I can fake that.” As they leave the hearing room, Kim is congratulating Jimmy on the sincerity of his appeal, when she is interrupted by his exuberant declaration that it was all a sham, and renaming himself, “Saul Goodman,” punning on “s’all good, man!”[25] Thus begins Saul Goodman’s developing career as a criminal lawyer, colluding in the crimes of his own defendant clients, including his participation in the rise and fall of Walter White’s empire.

It can be argued that Jimmy’s various exercises in self-deception long predated this pivotal event in Better Call Saul. But it more often seems like Jimmy was attempting to deceive himself, but without great success. He tries to deceive himself, for example, that he can be a buttoned-down attorney at a strait-laced law firm when he briefly joined the Santa Fe firm, Davis & Main. But that quickly became undone. More importantly, however, is that he tries to deceive himself into believing that he could be both Slippin’ Jimmy and have a career as an attorney who cut ethical corners, but stays just on the right side of the law and the New Mexico bar’s code of professional responsibility. Or perhaps it would be better to say, he thinks he can incorporate the skill of Slippin’ Jimmy into a legitimate law practice. And he seems to think he could carry on his side-gig of small time, relatively harmless grifts, as “Viktor” with his sister “Giselle” (aka, Kim Wexler). In any event, we all know how it turns out: Saul Goodman managing a Cinnabon in Omaha as Gene Tackovic, while his inner Slippin’ Jimmy struggles to emerge.

The emergence of Slippin’ Jimmy in Omaha leads to Saul’s arrest and extradition to New Mexico. Initially, Saul cut himself a great deal by exploiting his knowledge of criminal procedure and playing on the prosecutor’s potential embarrassment of a not-guilty verdict. From a long list of felonies calling for sentences of life plus 190 years in prison, Saul negotiated a guilty plea on a single felony, for a seven-year sentence, much to the dismay of Marie Schrader. In the context of the negotiation, he also intimated that he could implicate Kim Wexler in his crimes. This induces Kim to fly from Florida to New Mexico for Saul’s trial.

This leads to perhaps the most famous and important scene in BCS, in which Saul makes a full confession. The timing of Saul’s decision to confess to his crimes is not clear. Did he really intend to implicate Kim, but was dissuaded when he saw her in the courtroom? Or was his implication of Kim in his crimes a ruse to get her there, having already planned to confess and wanting her to witness it?

In any event, against the protestation of his lawyer and the admonition of the judge, Saul gives a complete and undiluted confession of his full, voluntary complicity in the crimes of Walter White, repudiating and contradicting his own prior sworn statements from the plea negotiation. This confession included his indispensable collusion in building Walter White’s drug empire and his guilt as accessory-after-the-fact to the murder of Hank Schrader and Steve Gomez. Saul confessed his sins without regard for the potential punishment. And he admitted that he had lied about Wexler’s alleged complicity, clearing her of association with his crimes in Breaking Bad and the death of Howard Hamlin in Better Call Saul.

In the courtroom chaos that ensued, Saul became completely transparent. “The name’s McGill,” he tells the judge after she calls him “Mr. Goodman.” “I’m James McGill.”[26] James McGill is no longer engaged in the self-deception that had defined Saul Goodman’s career. While he cannot undo the harm that he has committed, he can repent of it. And his repentance is both represented and completed in the confession of his name. The self-deception is over. As a result of his confession and plea of guilt, Jimmy is sentenced to eighty six years in the very maximum-security prison he had previously negotiated himself out of. Kim had already made her own confession of complicity in the events leading to Howard Hamlin’s murder. But because no evidence of a provable crime could be brought against her, Kim’s sentence—writing marketing copy for a Florida sprinkler company and working in a legal aid clinic—was somewhat less harsh than Jimmy’s.

In the final scene of Better Call Saul, Kim visits Jimmy in prison, where they share a forbidden cigarette in the interview room, a scene deliberately reflecting a similar one in the parking garage of Hamlin, Hamlin & McGill some time earlier. “Then, as Better Call Saul (and thus the Walter White saga) closes, Kim walks freely from the prison, presumably back to her legal aid purgatory. And Jimmy watches her depart from behind the bars of the prison yard, from which he will never emerge.”[27] But the man Kim leaves behind, James McGill, seems to have fulfilled the necessary—and perhaps even sufficient—condition for his redemption.

EDITORIAL NOTE: A version of this paper was delivered at the Gilligan's Archipelago: Justice and Mercy in "Breaking Bad" and "Better Call Saul" Conference. You can listen to an interview with the author of this essay on Church Life Today soon.

[1] Stanley Hauerwas, Hannah’s Child: A Theologian’s Memoir (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2010), Kindle edition, location 3449 of 4068.

[2] David Burrell and Stanley Hauerwas, “Self-Deception and Autobiography: Theological and Ethical Reflections on Speer’s Inside the Third Reich,” in Hauerwas, Truthfulness and Tragedy: Further Investigations into Christian Ethics (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press 1977), 82.

[3] Burrell and Hauerwas, “Self-Deception and Autobiography,” 84.

[4] Burrell and Hauerwas, “Self-Deception and Autobiography,” 86.

[5] Burrell and Hauerwas, “Self-Deception and Autobiography,” 86.

[6] Burrell and Hauerwas, “Self-Deception and Autobiography,” 86.

[7] Burrell and Hauerwas, “Self-Deception and Autobiography,” 87.

[8] The episode was originally titled, “Everybody Wins,” a line taken from the same scene as “Say My Name.”

[10] Burrell and Hauerwas, “Self-Deception and Autobiography,” 86.

[11] Burrell and Hauerwas, “Self-Deception and Autobiography,” 103. I will return to this point in my discussion of Walter’s final encounter with Skylar.

[15] Burrell and Hauerwas, “Self-Deception and Autobiography,” 86.

[16] As Walter Jr.’s sympathies swing against Skylar and in favor of Walter, Junior angrily demands that he be addressed again as “Walter Jr.,” complaining that his mother will not even say “Walter,” his father’s name.

[17] Burrell and Hauerwas, “Self-Deception and Autobiography,” 86.

[18] Burrell and Hauerwas, “Self-Deception and Autobiography,” 86.

[27] Craycraft, “‘Saul Over, Man’—Confession and Redemption in Better Call Saul,” in The Catholic Herald, Aug. 18, 2022.