Vast wounds remain. This was the conclusion of a consultation on the sex abuse crisis in the Catholic Church held at the University of Notre Dame in 2021. A day’s conversation involved theologians, therapists, church leaders, and lawyers, including several survivors of abuse and many activists in church affairs.

I had not necessarily expected this conclusion. The idea for the consultation was that of Dr. Katharina Westerhorstmann, a German theologian who has written and spoken on sex abuse in the church and was on leave at Notre Dame in 2019 when our president, Fr. John Jenkins, announced a grant competition for faculty to develop ideas for addressing the crisis in the aftermath of the revelations surrounding former Cardinal Theodore McCarrick. Dr. Westerhorstmann approached me because of my work as a scholar and activist in the efforts of nations to address the wounds of dictatorship, civil war, and genocide: South Africa and Germany, Argentina, and Rwanda. Might there be lessons here for the Church? We won a grant and organized the consultation.

The ritual opening exercise of participants giving their names and affiliations at once turned into a long session in which participants spilled their hearts and spoke of abuse and coverup that they had encountered and learned of. The group thought that many survivors had not been healed, much truth had not told, accountability was unachieved, repentance was inadequate, reforms were incomplete, relationships in the Church were hobbled, and the credibility of the Church’s message in the world was hampered. Uninhibited, over the course of the day, they discussed these wounds as well as what possibilities for healing and restoration might lie in the experience of nation-states.

To say that wounds remain is not to ignore the tireless efforts that so many have made in the Church to address the crisis, including those of many here in the audience. I am a latecomer to this issue and have learned of numerous inspired initiatives for healing, reform, justice, and accountability. The Church’s leaders have made important progress as well, working to build environments of protection, commissioning a thorough report of abuse, meeting with victims, voicing and conducting rituals of apology and restoration, developing global norms for accountability among bishops, and much else.

If wounds remain, though, what might be done to bring healing? In a quarter century of studying and participating in nation-states’ responses to past injustice, I have found that two paradigms often compete. One might be called a legal paradigm. It is carried by human rights activists, international lawyers, and diplomats and aspires to the rebuilding of the rule of law. Its dream is to place architects of atrocity in the dock of a court. The glass towers of the International Criminal Court in the Hague can be thought of as the cathedral of this theology.

The other paradigm does not reject these goals but posits a different center. It is associated often with the religious leaders who frequently have been involved in these national efforts. Let us call it reconciliation. Its aim is the restoration of right relationship and involves healing forms of truth-telling, empathetic acknowledgment, apologies, and even forgiveness. No Future Without Forgiveness was the title of Archbishop Desmond Tutu’s book about South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission of the late 1990s, which investigated the crimes of the apartheid period in South Africa’s history, and of which Tutu was the Chair. Reconciliation is most intensively voice and practiced in villages and byways, where, especially in poor countries, people have little choice but to live together again.

I perceive similar paradigms in responses to the sex abuse crisis in the Church. The secular logic of the journalist, lawyer, and therapist has dominated the scene. I would be the first to credit the journalists and the whistleblowers who have exposed abuses. It was public revelations in newspapers in 2002 and 2018 that spurred two major waves of intense reform in the Church. Similarly, it is difficult to imagine a just and effective response without the law—legal protection of children, justice for perpetrators, the provision of reparations, and sometimes what Fr. Dan Griffith of this diocese calls “big picture lawyering” a cooperative, constructive settlement between church and government lawyers that promotes multiple reforms. And, psychologists and counselors have brought healing to so many survivors whose lives were broken by abuse.

Yet vast wounds remain. Journalistic exposure has wrought reform but leaves untended the many wounds whose redress requires far longer effort than what scandal and outrage generate. Law has provided crucial justice but also has erected adversarial court proceedings that lead the Church into a protective crouch of denial to minimize gargantuan financial losses, while victims’ lawyers pursue damages that often elicit little genuine repair of lives. Therapists have furthered such repair for individual victims but often do little for the web of relationships torn by abuse, the ligatures of the Body of Christ.

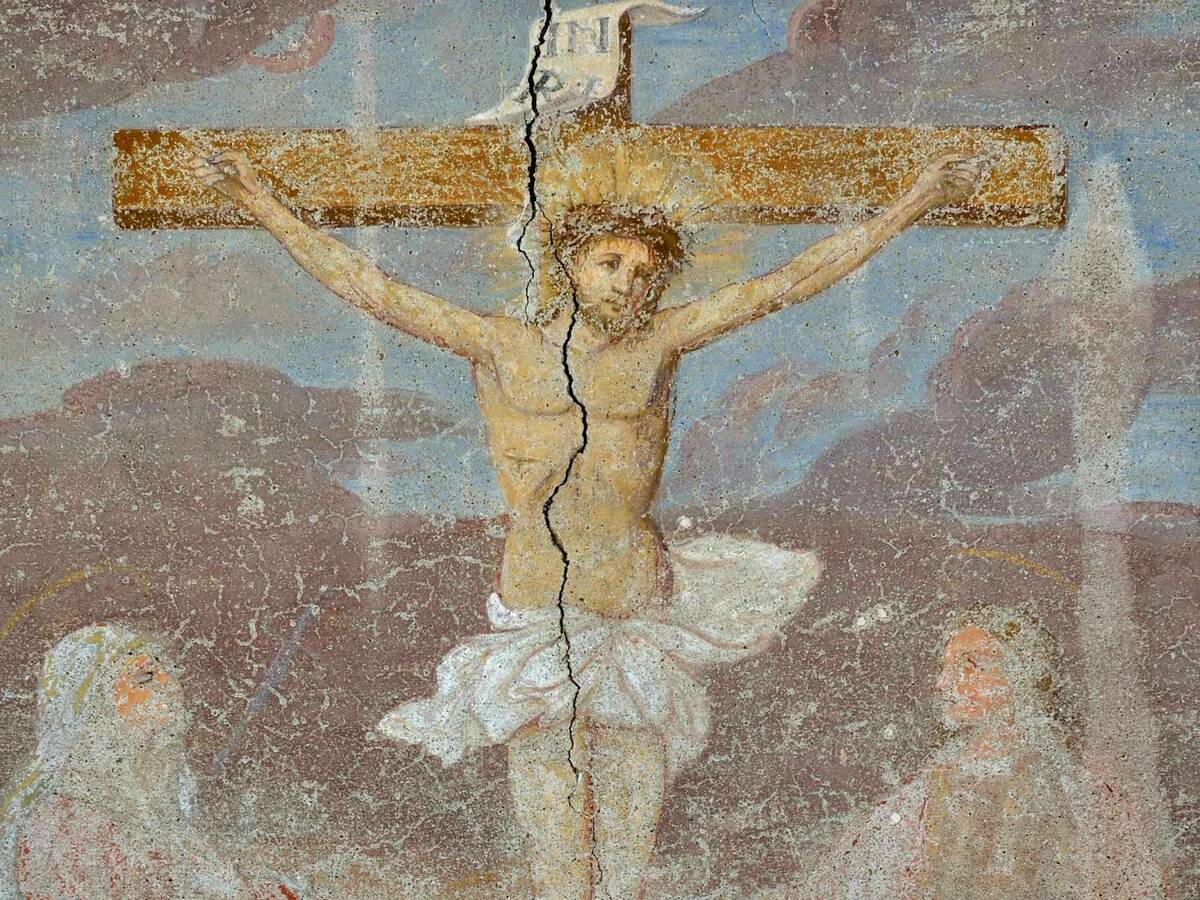

In parallel to the setting of nation-states, a different paradigm for the repair of the Church arises from adopting not centrally the standpoint of the journalist, the lawyer, or the therapist, but rather that of the Church itself. Were not the founding events of the Church ones of a response to vast and pervasive evil that aimed to restore persons and relationships to wholeness? The cross and resurrection of Jesus Christ, God’s reconciliation of the world, inaugurated a holistic restoration of victims, perpetrators, fellow members of the Church, their relationships, and indeed the entire heavens and earth. In the Eucharist, every Christian becomes conformed to this reconciliation and an agent of pursuing it. Pope Benedict XVI analogized the Eucharist to nuclear fission: it is potent to transform. What makes the Eucharist potent is that God does not convey a mere model or blueprint for the work of reconciliation but also incorporates every person into it. In Holy Cross College professor Emily Ransom’s article on her own response to sexual assault, she wrote: “Christ had been pierced but never sexually assaulted as I had been. In me, however, now he has, and now that is part of the story of our scandalous redemption. I have been forever changed from it, for better and worse, as has he.”

How might the cross and resurrection yield practices through which the Church could address the wounds that remain? I propose five respects in which the cross and resurrection restore persons and relationships and offer ideas about how the Church can participate in this restoration. I am inspired here by the book of the nineteenth-century Italian priest, Fr. Antonio Rosmini, Of the Five Wounds of the Holy Church, in which he identified five ills of the Church that correspond to the five wounds of Christ on the cross and proposed attendant reforms.

The first respect is solidarity with the sufferer, especially victims of injustice. In the Gospel of Luke, Jesus inaugurates his ministry by reading a scroll from Isaiah saying that the Spirit of God has anointed him to bring glad tidings to the poor, proclaim liberty to the captives, effect recovery of sight for the blind, and let the oppressed go free. In Jesus’s death on the cross, he becomes a victim of injustice and exercises solidarity with all victims of injustice and wills their healing through his resurrection. The Church acts as Christ, then, by exercising empathetic solidarity with the victims of sex abuse, who have suffered psychological damage, broken marriages, ruined careers, alcoholism and drug addiction, and suicide, and who include family and friends who have experienced the ripple effects of that abuse. The Church’s solidarity also helps it to accept responsibility for the actions of its own clergy who perpetrated the abuse, and who were, after all, distinctively charged with administering—and living—the sacrament.

One participant in our consultation told of heinous abuse that she had suffered at the hands of a priest as a girl. When she finally got authorities in the Church to hear her story, she was granted legal formalities and offered a six-figure sum of money as restitution, which she refused, saying that it made her feel like a prostitute. She found healing through therapy and came to enjoy a strong marriage and family, yet she has remained estranged from the Church for decades. Recently, she has found bishops who have walked with her, reminding us of those clergy who have exercised pastoral solicitude. There are many victims like her, though; right relationship has not been restored.

In the experience of nation-states, truth and reconciliation efforts are at their best when victims are given the opportunity to tell their stories before representatives of state authority as well as other citizens, friends, and family members. The South African Truth and Reconciliation is memorable for the many public hearings that created these opportunities. One victim of torture, Mzykisi Mdidimba, expressed that her testimony “has taken it off my heart . . . .When I have told stories of my life before, afterward, I am crying, crying, crying, and felt that it was not finished. This time, I know that what they’ve done to me will be among these people and all over the country. I still have some sort of crying, but also joy inside.” In Rwanda and Timor Leste, local forums allowed victims to testify before fellow villagers and community leaders. The point here is not just that an open telling of one’s story may be cathartic but also that the official, public character of the forums serves to defeat the standing legitimacy of crimes that were committed in the name of the political order and to restore the status of victims as citizens. So, too, the Church helps to restore victims not simply by encouraging their healing but also by involving its bishops and clergy in this healing.

The second restorative dimension of the cross and resurrection is the vindication of truth. When questioned by Pontius Pilate, Jesus tells him that he came into the world to “testify to the truth,” to which Pilate replies, “What is truth?” Through the cross and resurrection, Jesus overcomes and defeats this regime of lies and makes truth the definitive foundation for the Church and for social orders constructed on Christian principles.

The Church used to refrain from revealing egregious wrongdoing on the basis of the doctrine of scandal. Such knowledge would hurt the Church, its reputation, and its mission, so it was reasoned. Whatever validity this doctrine has had in isolated cases of wrongdoing, it makes little sense for sex abuse today, involving a widespread practice affecting thousands, the frequency of cover-up, which also creates scandal, and the critical role of truth as a precondition for further restorative measures. As Pope St. Gregory the Great was quoted at our consultation, “As much as we can be without sin, we ought to avoid scandal to our neighbors. But if scandal is taken from truth, it is better that scandal be allowed to arise than that truth be relinquished.” Pope Francis has called for the full telling of truth about Church sex abuse.

The importance of learning the truth about past injustices is the most widely agreed-upon principle among the nation-states who have faced their pasts. Over forty of them have established truth commissions to discover and reveal the crimes of a previous dictatorship, war, or other pattern of injustice. Closest to home, Canada held a national Truth and Reconciliation Commission from 2007 to 2015 to learn of abuses surrounding its residential school system, which led to public awareness of the abuses, reparations, and public apologies. Pope Francis’s recent apology to native peoples in Canada may be seen as an indirect fruit of this commission. Truth vindicates and acknowledges victims and defeats the legitimacy and lies of the officials who perpetrated abuse. It also essential for the legitimacy of a nascent democracy or peace settlement, accountability, reparations, apology, and forgiveness.

Truth furthers reconciliation when it is elicited in a way that also heals. In the 1990s, after decades of civil war in Guatemala, the Catholic Church there, dissatisfied with the government’s proposed truth commission, founded a separate truth commission. Its method for learning the truth about the abuses of the civil war was to train 800 animadores, or volunteers, to travel to villages and take the testimony of survivors of violence while also providing them with counseling, conducting a ceremony of remembrance for dead friends and relatives, and often constructing a memorial. The commission elicited the truth in a way that brought healing to survivors.

Similarly, knowing the truth is crucial in the Church today. The John Jay Report of 2004 commissioned by the U.S. Bishops profiled the number and kind of abuses of minors between 1950 and 2002. According to updated information from Bishopsaccountability.org, an organization that has provided the world with invaluable information on the issue, between 1950 and 2018, over 20,000 incidents of the abuse of minors took place at the hands of just over 7,000 credibly accused clergy, or about 6% of the total. An open question is: in what areas does the truth remain to be known? Some participants in our consultation held that sexual relations between priests and adults, ones fraught with the exercise of power, now ought to be brought to light.

But we need healing truth as well as forensic truth, to borrow terms that arose from South Africa’s experience. While the truth of what happened is essential for accountability and reform, truth and its mode of elicitation ought to seek not merely exposure but also restoration of the wounded. Such is the truth of the cross and resurrection. What is needed is a more textured account, voiced in the words of survivors, conveying what happened to them, how it hurt them, and what they hope for, an account whose content everyone in the Church would hear and be changed by. Exemplary are Guatemala and other truth commissions, which took the testimony of survivors in the empathetic and supportive hearing of loved ones, community members, and leaders—testimony that has “taken it off my heart,” in the words of Mdidimba. The second dimension of the cross and resurrection’s restoration, truth, converges with the first dimension, healing.

What kind of forums might gain healing truth is what we must explore. One mode of conveying healing truth is memorials. One of the participants in our consultation, Michael Hoffman, has established a healing garden for sex abuse victims in the diocese of Chicago, one that keeps the memory of victims alive and is often a site for healing Masses. Hoffman now proposes a national healing garden in Washington, D.C., which would offer the same for the entire country.

A third dimension of restoration is more provocative. It is less easily accepted, is widely omitted from the responses to sex abuse that I have encountered, and yet is integral to the cross and resurrection: the redemption of the perpetrator. I can hear instinctive outrage: how can we speak of the redemption of Cardinal McCarrick given the hurt he caused and the large network of silence surrounding his abuses found in the hierarchy of the Church? How can we speak of redemption for Fr. John Geoghan, the superpredator in Boston whose actions and failure to be removed from harm’s way on the part of the Church was the most memorable part of the Boston Globe article of January 2002 that made the abuse crisis public in the United States? Yet when I read that Geoghan was murdered by a fellow inmate in his first year of prison, I could not help asking: had not Jesus died for him too?

Christ’s mission to the world makes little sense apart from his redemption of sinners. “I have not come to call the righteous but sinners,” Jesus told Pharisees in the Gospel of Mark. In Jesus’s death on the cross, he paid the debt of sinners and enabled them to be redeemed, restored, and join him in his resurrection. All may enter the new covenant through repentance and penance. All greatly need to enter it.

This dimension does not condone or minimize the evil or the damage of sex abuse, the wrongness of covering up abuse or failing to remove abusers from harmful environments, or the critical role of accountability, also a dimension of restoration, one that remains widely unfulfilled. We should be wary of the President of El Salvador, who, just after his country’s truth commission report was released in 1992, spoke of reconciliation, which really meant moving on without accountability, reform, or repentance. Repentance makes little sense if evil is overlooked, lessened, or diverted.

Any mode of redemption for the perpetrator must also respect the welfare of the victims. What does this mean? It was frequently said at our consultation that when you have met one victim you have met one victim. Some survivors plea that a face-to-face encounter with a perpetrator would be too traumatic or something for which they are not yet ready. Others differ. One survivor at our consultation said that he had foregone a trial and wished instead for a meeting with his perpetrator and his bishop. Emily Ransom was intent on meeting with the priest who abused her because, she wrote, she loved him, still considered him a friend, and believed that were he presented with his wrong he would be open to repenting and receiving forgiveness. She initiated a meeting with him, where he was evasive at first but then proved repentant and willing to confess his deeds to his superiors. When she later sought to follow up with his superiors, though, they gave her a lay advocate who never spoke with her and told her never to have contact with the priest. What she got was law and institution, not cross and resurrection. The procedures are understandable given the law and the liabilities. Still, this rebuff of her effort to respond in Christ at the hands of the Church that she had joined hurt her more than the initial assault.

Might it also be said that when you have met one perpetrator you have met one perpetrator? Might not their knowledge and intentionality differ? Their histories? Their willingness to change? Their capacity for yet making a positive contribution? For the perpetrator, redemption means taking responsibility, repenting, apologizing, and accepting penitential consequences. This is valuable in its own right but also, as national experiences have shown, providing a space for the perpetrator’s repentance can contribute to further restorations. The repentance of government officials who have committed human rights abuses has not been common in most of the nation-states I have studied, yet it took place in notable high-profile cases in South Africa. It was encouraged, to be sure, by the immunity from prosecution granted to those who told the truth of crimes but also by the atmosphere of forgiveness and reconciliation there. Such apologies delegitimate previous injustices, bolster the legitimacy of the new regime, and bring healing to victims, whose narratives can reciprocally encourage repentance.

In the church, popes and numerous bishops have held Masses of reparation, voiced apologies, and proclaimed national days of repentance. As scholar Michael Griffin has pointed out in his book, The Politics of Penance, though few of the bishops or priests who themselves committed or covered up abuses have apologized for their own actions.

The healing of survivors and of perpetrators are not at odds, but are rather, each in their own way, a part of the restorative work of the cross and resurrection. Might there be forums in which this complementarity is realized?

A fourth dimension of Christian restoration is likewise one that is mentioned rarely in the debate surrounding sex abuse in the Church yet is also inseparable from the cross and resurrection: forgiveness. Forgiveness is also either ignored or strongly criticized by scholars and activists involved in national processes, even by ones who adopt reconciliation as their paradigm. They hold that forgiveness places the burden of repair on already disempowered victims, frees the powerful from accountability, and is simply unrealistic and unpracticed. These criticisms have merit to them and must be taken seriously.

Yet it would be difficult for a Christian to set aside forgiveness. Catholics affirm and ask for help in forgiveness every time they recite the Our Father prayer. A Rwandan refugee friend of mine whose father was killed before her eyes when she was five years old used to close her lips when the prayer reached the words “as we forgive,” an admirable honesty and attentiveness to the prayer, until she later forgave from her heart and resumed the words. In the Gospel of Matthew, when Peter presses Jesus on forgiveness, Jesus responds that Peter ought to forgive “seventy times seven times” and continues with one of his starkest parables, that of a servant whose king forgave him his unpayable debt but then refused to forgive his own debtor—and was thus thrown into debtor’s prison.

But how is this teaching anything but hopeless or even harmful idealism for a survivor of sex abuse—or of torture, or of the abduction of one’s husband? Jesus’s ethic of forgiveness becomes plausible only through his own act of forgiveness, through which he wills to heal radically the victim and perpetrator alike. Forgive because God has forgiven you, Jesus teaches, and he performs this forgiveness on the cross, where he forgives his perpetrator and also all of humanity. The cross alters the configuration of power involved in forgiveness in a way that makes it a very different kind of act than one that takes place only between the victim and the perpetrator. If the perpetrator vastly dwarfs the victim in his power and the magnitude of his deeds, as is often true in clerical sex abuse and in the evils of war and politics, then forgiveness may well become destructive and dystopian. But in Christ, forgiveness is a three-party proposition where the third party is the creator and redeemer of the universe, one who dwarfs the power and evil of the perpetrator and incorporates the victim into himself on the cross so that the victim’s act of forgiveness is indeed Christ himself forgiving through him or her. Towards the perpetrator, this forgiveness is not merely the blotting out of a debt but also the grace to change and be created new. Forgiveness, though, also brings about strength and healing for the victim, who regains agency as a healer and a builder of peace, following the pattern of Christ.

A reviewer of my book, Just and Unjust Peace, apprised the book positively but questioned forgiveness, which he thought is only practiced by rare saints and is usually dangerous. So, I secured a grant to study whether forgiveness really takes place after armed conflict, surveying 640 residents of war-torn regions of Uganda. I learned that sixty-eight percent of victims of violence reported having practiced forgiveness and that eighty-six percent of respondents favored the practice of forgiveness even in settings of nightmarish violence. The vast majority of respondents were Christian, and they most commonly cited their faith as the reason why they forgave. In speaking with forgivers in focus groups and interviews, I learned that while forgiveness was not facile or automatic, people had been healed and strengthened by it, seeing it as an act of peacebuilding.

One such person was Angelina Atyam, who forgave the soldiers in the rebel Lord’s Resistance Army who abducted her daughter along with 130 other girls from a Catholic boarding school in 1996. Like my Rwandan friend, Angelina was challenged by the words of the Our Father, which she prayed weekly with other parents of the abducted girls. She sensed and followed a call to forgive, came to advocate forgiveness widely, and even located the mother of her daughter’s abductor, through whom she forgave the abductor, his family, and his clan. When this soldier later died in combat, Angelina wept and consoled his mother. In my conversations with Angelina, I found the strength of a healer who had been healed.

The concerns of the critics have much to teach us. In a balanced article in Theological Studies, retired Judge Janine Geske and Professor Stephen Pope, both participants in our consultation, argued that forgiveness could be a positive response to sex abuse but also that it is prone to abuses. Their and others’ admonitions serve as guidelines for the practice. First, forgiveness must not minimize the wrongness or magnitude of the wrong or negate the victim’s rightful anger towards it. Second, the victim’s freedom to forgive—or not to—must always be respected and is crucial to the genuine performance of forgiveness. Third, forgiveness is neither an orphan nor a lone superhero but is meant to be accompanied by multiple other practices: accountability, reforms, acknowledgment, and repentance. As Fr. Thomas Berg and Dr. Timothy Lock argue in their new book Choosing Forgiveness: “In the context of the Church’s sexual abuse crisis, forgiveness is conceived of as an extraordinarily positive and empowering action on the part of the victim . . . . By the same token, forgiveness is compatible with just anger toward the offender, anger aimed ultimately at the offender’s own good. It can accommodate both the remission of punishment or the administration of appropriate punishment for the good of all: the victim, the other stakeholders, and, again, the perpetrator.”

The fifth and final dimension of restoration I wish to discuss is Christ’s founding of the Church, which he did through his cross and resurrection and does over and again through the Eucharist. Recipients of the Eucharist are made into a family, the profoundest meaning of the Church, where they, victim, perpetrator, and every other member, all children of the Father, care intensely for one another’s restoration. What cross and resurrection imply for the sex abuse most of all, I propose, is that the Church would be a place, and provide forums, where the multiple forms of restoration that I have discussed would take place together, each reinforcing the other, brought about through interaction between all those involved.

In nation-states, these kinds of forums could be found in healing circles such as Fambul Tok in Sierra Leone and Mato Oput in Uganda, both rooted in tribal traditions. Mato Oput involves a ceremony among the whole community, held before village elders, in which apology and forgiveness are voiced, restitution is agreed upon, and the whole village affirms the restoration of friendship so that the community can move ahead. Both victims and offenders prepare for months with village leaders. These practices are remarkable in combining several dimensions of restoration.

They manifest what in the West is known as restorative justice, which addresses the wide range of harms caused by a crime and actively involves all who were affected by it. With regard to the sex abuse crisis, restorative justice is taking place today in the form of healing circles in certain dioceses, most extensively in St. Paul and Minneapolis, and nobody has done more to promote them than Judge Janine Geske. The circles bring together survivors, representative offenders, non-offender priests, church employees, and stakeholders. They allow survivors to tell their stories, receive the empathetic acknowledgement of others, including spokespersons for the church and for offenders, and to come to understand themselves as beloved members of the Church community, rather than one who is shamed, stigmatized, or forgotten. People involved have found healing, though it is never complete.

Reflecting restorative justice have also been forums such as the recent Independent Reconciliation and Reparations Programs in the Philadelphia Archdiocese, which have awarded financial reparations to victims of childhood clerical sex abuse under the authority of an Independent Oversight Committee composed of prominent citizens. With the assistance of a Victim Support Facilitator, victims gain the opportunity to tell their story and receive compensation in an alternative to litigation, an adversarial process that often takes years. Victims have expressed appreciation for these forums, which some thirty dioceses have adopted.

Might restorative justice forums in the Church be spread throughout the United States and elsewhere in the world? I wish also to invite dialogue on the question of whether perpetrators can be brought more fully into such forums. I know that the question is a sensitive one and that many victims are understandably reluctant to attend such an encounter. Yet, always respecting the freedom of participants, might such a possibility be approached gradually—perhaps through the extensive preparation of both sides, or in a later forum, not the initial one, or in other ways? Might there also be ways of approaching accountability and reparations through restorative justice forums as an alternative to the law court, where these matters are typically decided in an adversarial fashion that deepens divisions and often stunts empathy, repentance, truth-telling, and repentance? I do not have definitive answers to these questions but wish to raise them here.

An approach based on the restoration of relationship, grounded in the cross and resurrection of Jesus, we must remember, will be partial, ongoing, and incomplete in this life. Reconciliation is criticized sometimes for its prefix, re-, said to aspire to return to a golden age that never existed. In a Christian view, though, reconciliation does not seek to recover a historical moment within national or Church history that was once free of conflict but is rather God’s intervention into time from outside of time and will only be complete at the end of time. Through the Spirit, though, we may be confident that we can see progress toward reconciliation.

Healing in the matter of abuse may in turn help to restore the credibility of the Church at a time when studies show that Catholics, especially the young, are leaving the Church and are citing sex abuse as a major reason for it. Were the Church to address its brokenness not in reaction to a court summons or public outrage but rather through its own initiative, on the basis of its founding events, its credibility, and its evangelical message would regain strength. So too would be our bishops’ call for a revival of the Eucharist, whose nuclear fission would be demonstrated.

We can dream further that the Church’s work of mercy might leaven the world around the Church. Indisputably, sex abuse has taken place in many other institutions. The Church might offer an example of an institution that heals by acting as more than an institution. Emily closes her piece by holding out the possibility of “the Church’s gift to our culture":

The #MeToo movement for all its invaluable contributions to public discourse is not in the position to explore healing as the Church is, and perhaps rightly so. But as a culture, we are hurting for our underdeveloped understanding of remorse, apology, forgiveness, healing, and rehabilitation. We have learned how to [out our perpetrators] but not what to do with them when they are out, especially if it turns out [they] are in each of us, and thus fear and anger ravage us without a place to go. And the silent survivors who for whatever reason do not desire retribution do not have the agency to seek a redemption that no one believes is possible.

In the Church, however, it is not only possible; it is a fundamental part of our DNA. We can bring victims to the table in meaningful ways, not only hearing their stories but inviting them into the conversations in which decisions are made. We can walk beside them on the long road of healing, understanding that their wounds are our wounds, and that any rupture in their relationship with the Church hurts us all. Without suggesting a moral imperative for victims, our familial identity declares the hope that real, concrete, temporal healing exists.

More than once, I have been asked whether the abuse crisis has shaken my faith in the Catholic Church. I answer that my belief in the cross and resurrection and the Church’s unshakeable roots in these events have kept my faith firm. This answer, though, can only be credible if “answer” means not just “argument” or “apologetic” but also an active, attentive response to the terrible wounds that have been suffered in the Church. The cross and resurrection will be believed only if they are lived.

Editorial Note: This was first delivered as an address at the University of St Thomas Law School in St. Paul, Minnesota on September 15, 2022.