SPOILER ALERT!

To watch 1917, the Sam Mendes film about two British soldiers on a perilous mission in World War I, is to journey across the trenches and devastated countryside of the Western Front. The film takes place over the course of a single day and night: April 6, 1917—a date that is not significant for the purpose of the plot, but which is the day the United States entered the Great War. My hunch is that Mendes chose that date because it is the date we Americans enter the war as well. The most distinctive element of the film—that it is presented as one, continuous shot—enlists viewers as a third party to this mission.

From the moment they wake from a nap in a spring breeze safely removed from the front line, we never leave the side of lance corporals Tom Blake and Will Schofield. We walk with them into the trenches to receive their mission: deliver an urgent message to a general 15 miles away who is positioning his 1,600 men to charge into a trap. We climb over the embankments into no-man’s land with them as they make their way through barbed wire and dead men and rotting horses into recently-abandoned enemy territory. We run through destroyed French cities and float along corpse-ridden rivers with them as they make their way to save the battalion—and Blake’s brother, who is among the men to lead the attack.

The unique storytelling technique is surely one reason the film has been nominated for a number of Oscars. It is also a clear example of what Catholics will recognize as a sacramental approach to art. If a sacrament is a symbol that effects what it signifies, this film succeeds in incarnating the horror of war for our imaginations. The viewer leaves with a visceral feeling of what the experience was like for those who fought and died.

In fact, the film gets even more explicit with Catholic imagery. In part, this is because the story reflects the worldview of those who fought in the Great War, but I think Mendes is up to something more. The construction of the references points to an effort to deliberately grab hold of this sacramental worldview and use it as a cinematic tool.

One of the first things we learn about Tom after he wakes up is that he had considered entering the seminary. As the two set out, Tom asks if he missed a meal because he is hungry. Will then pulls from his breast pocket a single slice of bread, thin and white. He breaks it and shares it with Tom. It is not nearly enough to sustain anyone, but the reverence with which it was carried, broken, and shared is a clear signal to Catholics to think of the Eucharist. Given the dangers of their mission, it serves as a sort of viaticum—bread for the final journey.

When they reach the front lines, they meet a caustic captain who cynically accepts their mission as just one more absurd twist of a nonsensical play in which he is a leading character. He points the way through no-man’s land for them, then uses his flask as a makeshift aspergillium, sprinkling them with either water or gin, and incants the Latin phrase for general absolution—te absolvo—before they depart.

Other sacramentals dot the film. Most notably: cherry blossoms. The retreating German troops chopped down an entire orchard in bloom, and Tom and Will comment on the different varieties of cherries and how the blossoms would release from the trees and fall like snow. Tom says that these fallen trees will sprout saplings—in time, there will be even more trees crowding the orchard. At a crucial moment later in the film, as Will is nearly drowning, he is awakened by falling cherry blossom petals and the viewer recalls not just their conversation, but the resilience they adopted in that orchard.

Another example: Will arrives at the front lines in the middle of a silent forest and suddenly hears a single voice singing a haunting hymn. He follows it to find a company of soldiers, packed for war, reflectively gathered around a single doughboy. They all recline in a solemn reverie—it is a moment of rest for Will, but as soon as the song is over, the company springs into action and heads for the attack. The song mesmerizes. In the shaded glen, the soldiers (and us, sitting with them) receive it solemnly as a last moment of beauty and refuge.

In very real and literal ways, Tom and Will are venturing into the jaws of death. Each in their own way, they begin and end in the same place—at rest in the grass under a spring sky. The sacrifices they make and witness along the way reveal to us the cost of war on humanity—a cost people must pay, willingly or unwillingly.

Towards the end of the film, Will meets Tom’s brother, Joseph, who asks his name. His response excavates for us the layers of Will’s identity: he gives his military rank first; then his last name, Schofield; then his given name, William; and then, finally, the name he’s known by: Will. That core part of his identity—his “willingness” if you will—is the one thing that pulls us through the scarred landscape with him. Is the one thing that all soldiers offer in their service.

One of the first wounds Will sustains is a gash in his hand as they cross through some barbed wire—blood gushes down his palm, but they push on. As they dive for cover in a bomb crater, Will’s wounded hand plunges into a dead man’s chest cavity. He is repulsed of course—we all are, because we are sitting next to him, breathless—but the imagery is striking. His very own passion is leading him to shed his blood as he reaches into the depths of death itself to save others.

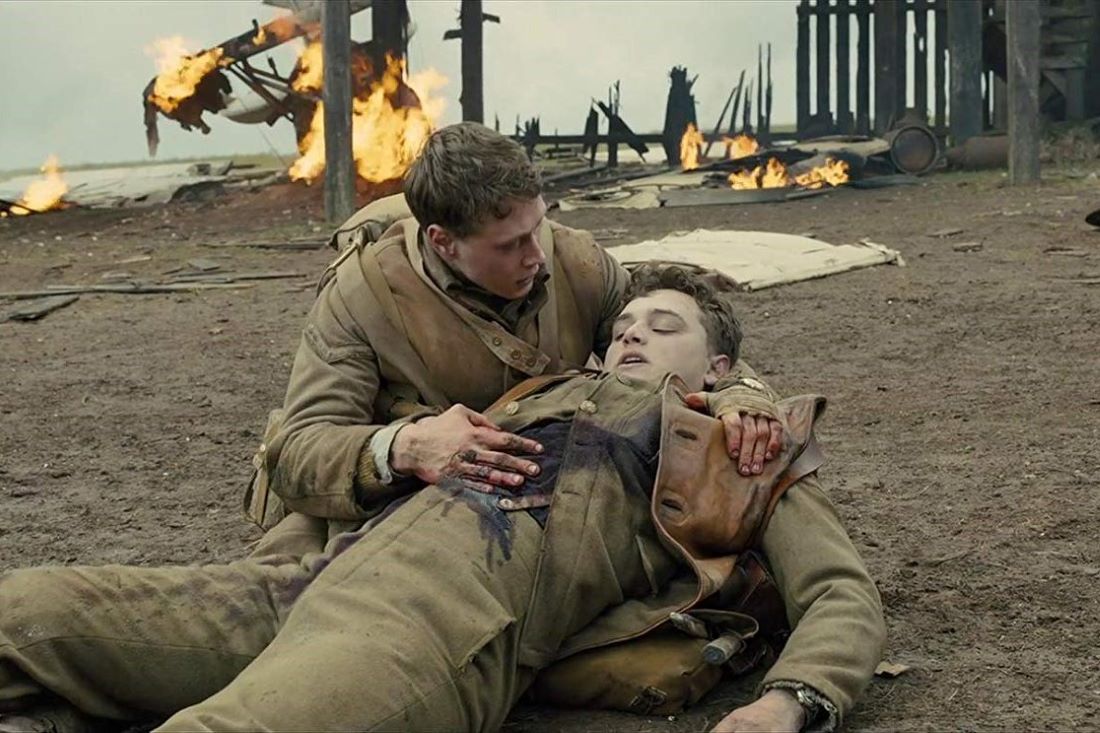

The two sustain other wounds that characterize Christ’s crucifixion. Tom is stabbed in his side. Will falls and gashes his head open. The two carry the crucifixion in their bodies in their own version of the way of the cross. One wonders if Mendes, himself, is reaching into our chest cavities with the wounds of these characters in order to touch our hearts. I know he touched mine.