The fullness toward which every human life tends is not in contradiction with a condition of sickness and suffering . . . the call to human fulfillment does not exclude those who suffer.

—Pope Francis, “Messaggio ai Assemblea Generale della Pontificia Accademia per la Vita”Human beings would have been created uselessly and in vain were they unable to attain happiness, as would be the case with anything that cannot attain its ultimate end.

—Thomas Aquinas, De MaloA life [of disability, handicap, or illness] does not mean a life with less potential for holiness . . . [the command] to “glorify God in our bodies,” does not apply only to the moral behavior of those of us who are physically well.

—John Paul II, “Address to the sick and handicapped in Brisbane (Australia)”

Integral to the Catholic account of our life in Christ is the commonsense recognition that some people have a profound, lifelong cognitive impairment. Correlative to that recognition is the Catholic presumption that severe intellectual disability cannot alienate a person from the grace of God. On the Catholic view, no disability and no measure of cognitive impairment can undermine the sanctifying gifts and perfecting work of the Holy Spirit. In other words, in and through the sacrament of Baptism, every Christian is called to the happiness of beatitude and every Christian is made capable of the holiness called virtue.

What I want to say concerns the Catholic understanding of the vocation and graced freedom that belong to adult Christians who have a profound, lifelong cognitive impairment and who have been in that condition since birth. In the language provided by the Code of Canon Law, these are adult Christians who “lack the use of reason.” I want to show that Catholics have a way to think about the properly human happiness and holiness of Christians who lack the use of reason. In doing so, I would like to address a contemporary theological doubt about the moral aptitude of adult Christians who are thus impaired. Specifically, some contemporary theologians question the capacity of those who lack the use of reason to actually know and actually love God and thus question the ability of such persons to live happy and holy lives. In other words, some theologians doubt that those who lack the use of reason are capable of virtue. I believe those theologians are mistaken.

My remarks are divided into four parts. First, I will discuss Catholic teaching on the virtues, contemporary virtue ethics, and the contemporary challenge of cognitive impairment. With respect to that contemporary challenge, I will make my personal stake in these themes explicit. Second, I will recall Catholic teaching on the creaturely dignity, wounded condition, and two-fold destiny of the human being. Third, I will recall Catholic teaching on the healing and perfecting gift of sacramental grace. Fourth, drawing upon St. Thomas Aquinas, I will describe the capacity of those who lack the use of reason for human happiness and Christian virtue.

The Catholic Virtue Tradition, Virtue Theory, and the Challenge of Cognitive Impairment

At the heart of the Catholic virtue tradition is the view that the perfection and happiness of the human being is to live in a way that reflects and perfects the attribute that is most distinctive to our specific nature. In other words, Catholics believe that human beings are composite creatures (a unity of body and spirit) whose creaturely dignity consists in our natural capacity and desire for knowledge and love of Creator God; and Catholics believe that the perfection and greatest good of our nature is to know Divine Truth and to direct ourselves toward loving participation in the Divine Good. So conceived, the creaturely perfection of the human being is a particular kind of activity that is performed in a particularly human way—involving both those material and immaterial aspects of our composite nature. The “virtues,” on the Catholic view, are stable spiritual-corporeal dispositions that make it possible for us to live in a way that is consistent with our nature and oriented toward our creaturely good and proper happiness.

All faithful Catholics affirm the inviolable dignity of every human being, from conception to natural death—and this affirmation includes persons who have a profound cognitive impairment. Nevertheless, some contemporary theologians (who unambiguously affirm and defend the dignity of every human life), have difficulty accounting for the human happiness and, in particular, the virtue of people who have a profound, lifelong cognitive impairment. The contemporary theological difficulty can be sketched in three theses:

-

Because the human being is a composite creature, properly human flourishing involves our corporeal faculties and powers.

-

Of those faculties and powers, the capacity for reason uniquely distinguishes the human being from other animals.

-

Specified by reason, the flourishing and happiness of the human being is a form of life that reflects and perfects our rational nature (i.e., the happy human life—the life of virtue—is a life lived according to reason)

The theological accounts of human morality that concern me are more nuanced and studied than the two-dimensional caricature I have just provided. Nevertheless, it is not difficult to find scholarly formulations of the Catholic virtue tradition that neatly map onto those three theses—theological accounts that, for the most part, do not consider the implications that I am interested to address in these remarks: namely, it follows from those three theses that human beings who lack the use of reason in a profound way cannot acquire and actualize the dispositions (i.e., the virtues) corresponding with properly human happiness. It is not enough to defend the moral subjectivity of profoundly impaired persons while omitting serious discussion of the moral agency and moral potential of persons who lack the use of reason. The problem, I contend, is that many of these moral theologians subscribe to a theory of the virtues that is premised on an incomplete account of the human being.

Christianity and Virtue

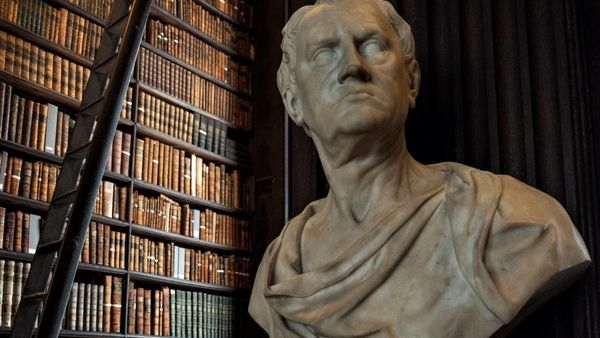

There is nothing exclusively “Christian” about virtue-based accounts of morality. As one way of describing and evaluating the goodness (and badness) of human acts, the various pre-Christian virtue traditions share in common the view that human flourishing (i.e., happiness) consists in the performance of stable character traits or dispositions (i.e., the virtues), which are formed through the practical training of one’s rational faculties and moral outlook (phronesis). It is important to note that the good disposition of the rational faculties was central to the virtue traditions that exercised the greatest influence upon the various Christian understandings. Within the Christian moral tradition, the accounts of moral virtue provided by Plato, Aristotle, and Cicero were by far the most influential—e.g., through St. Augustine’s engagement with the Platonism and Neoplatonism of Late Antiquity and St. Thomas Aquinas’ engagement with Aristotle in the thirteenth century.

The contemporary use of virtue ethics in Catholic moral thinking is complex, so generalization has limited utility. Nevertheless, few would contest that a key feature of the contemporary recovery of virtue ethics in Catholic moral thinking has coincided with a renewed appreciation for Aristotle’s theory of the virtues, as Aristotle’s theory was appropriated and revised in the theology of Aquinas. What exactly Aquinas appropriated and what exactly Aquinas revised has a bearing on how Catholics understand the moral aptitude of Christians who have a profound, lifelong cognitive impairment.

According to Aristotle’s theory of the virtues, the acquisition of properly human moral virtue is an arduous task that requires functionally intact and fully developed cognitive capabilities. Aristotle believed that some human beings were incapable of achieving the moral perfection (telos) proper to rational human nature (eidos)—for example, those who lack the use of reason (i.e., his postulated “slave by nature”) or those whose use of reason is impaired (i.e., women, due to their allegedly unruly passions, and all non-Mediterranean foreigners, due to an alleged imbalance of the internal thumos).

Aristotle maintained that some “natural slaves,” some women, and some non-Mediterranean foreigners were able to realize qualified human goods and a species of moral virtue—he thought there are “good slaves,” “good women,” and honorable barbarians; however, their moral goodness was coordinate with each class’s role-defined relationship (or friendship) with a particular well-born, well-formed, and fortunate adult male.

The problematic tendency among contemporary moralists is most acute when the Christian understanding of our creaturely dignity and fulfillment as the image of God is conflated with Aristotle’s rationalistic account of human nature and Aristotle’s understanding of the perfection of human nature. Parallel to Aristotle’s view that “those who do not possess reason” cannot attain the virtues, hasty theological appropriations of Aristotle’s anthropological premises have made it difficult for some contemporary moralists to account for the happiness and holiness of Christians who have a profound, lifelong cognitive impairment. It should be admitted that the problem I am describing here is not immediately apparent (nor even noteworthy) when Christian virtue ethics is articulated in general terms, about average folks who find themselves navigating common, everyday circumstances. However, to paraphrase and update a broadly Thomistic judgment: we should take pains to avoid the pseudoscientific folly that warps one man’s “for the most part” into the “necessary and always” of metaphysically stipulative principles.

There are occasions when the very useful Aristotelian shorthand ought to be set aside in favor of the more accurate (and tradition-substantiated) Christian distinction between our intellectual nature (as spiritual-corporeal beings who know and will) and the usual expression of that intellectual nature in the use of reason.

The Contemporary Problematic Tendency and the Challenge of Cognitive Impairment

Some Protestant theologians have noticed the problematic tendency I have just sketched. And the allegation has been made that the tendency discloses a problem (or, in more generous terms, a tension) at the heart of Roman Catholic moral teaching on the virtues, to the extent that the Catholic virtue tradition makes use of the teleological conception of human nature generally associated with Aristotle and Aquinas.

So, what is the alleged problem? Hans S. Reinders describes his understanding of the challenge that profound cognitive impairment presents to traditional Catholic moral theology. He focuses, in particular, on what he dubs “the Aristotelian-Thomist concept of the human good”:

Because the [Roman Catholic moral tradition] defines the human good in terms of our capacities for reason and will, there is no way in which human beings with a profound intellectual disability can be said to participate in the human good. They are part of a community of [human] genealogy; [but] they cannot be part of a community of [human] teleology . . . everything that is important about human life, according to the Roman Catholic view, is necessarily related to the perfection of our natural capacities . . . The position put forth by the Magisterium leaves no basis whatsoever to account for disabled lives from a teleological point of view . . . I am not arguing against the Magisterium’s stance against liberal bioethics [i.e., the Catholic claim] that the origin of human life is a sufficient reason for its protection. But we need not only be able to identify a profoundly disabled infant as a human being in the sense of origin; we also need to face the task of saying what the end of that child’s life as a human being is—from a Christian perspective. This is why ethical reflection on the lives of persons with profound disabilities must go beyond questions of rights and protections.

It is clear that Reinders’ account of “the” Roman Catholic view is a caricature and foil for his constructive proposal—and he openly admits to this interpretive agenda with a quick, though not insignificant, gesture. In spite of the various interpretive problems that follow from Reinders’ methodological approach, I have drawn attention to his critique for two reasons. First, it should be admitted that the caricatured “concept of the human good” with which Reinders is principally concerned does indeed reflect a form of theological shorthand that Thomistically-minded moral theologians occasionally use in an undisciplined way—specifically, the use of exclusively rationalistic terms when discussing the nature of the human being, human flourishing, or the perfection of the human being. However, the main reason that I have included the extended quote from Reinders strikes closer to home.

Vicente

Vicente is my older brother. From the day of his birth (which was also the day of his Baptism), Vicente has lived with a profound cognitive impairment. As a point of comparison, my brother’s measurable cognitive aptitude as a thirty-eight-year-old man is similar to that of a five-month-old infant—which means, among other things, that Vicente does not talk, he cannot walk, he cannot take care of himself in any meaningful way, and, as far as we can tell, my brother does not understand our words when we speak to him.

My brother Vicente has dark-brown eyes, sharp cheekbones, and thick black hair. His arms are long and muscular, but the rest of his body is stiff below the chest. Bathing, diapers, medication, grooming—Vicente’s health, cleanliness, and general well-being depend entirely upon the attention and care he receives from our family. He does not make eye contact, but Vicente has always had an open and receptive posture toward whatever is happening around him.

Vicente spends his days napping on a vinyl recliner, gnawing on his toys, and swinging his arms to the sound of country music. My brother’s life is filled with family, laughter, and good food. He likes oatmeal with brown sugar but absolutely abhors mashed potatoes. Although Vicente is quick to smile and enjoys being teased (like a towel briefly draped over his head), he has a serious personality—sometimes he is grumpy and impatient. Other times he’s silly or bored or anxious. On occasion, Vicente seems to be rapt in contemplation, attending to other-worldly concerns—but I am only guessing about what he is experiencing in those quiet moments. The fact is, we do not really know how Vicente experiences the world. However, there is no question, on the Catholic view, that my brother is actually experiencing the world and that what he knows of the world is understood and desired in the specifically human way.

However, because of Vicente’s impairment, it is easy for some people to overlook or simply ignore what is honorable (i.e., virtuous) in the subtle and simple acts that express his moral character. Some Catholic moral theologians claim that people like my brother lack actual knowledge and actual love of God, and they claim that people like my brother are incapable of properly human happiness or the holiness of Christian virtue. It is viciously unjust when scholars make reviling claims to the detriment of another’s honor and to the diminishment of the respect that is due.

It is a matter of justice—not only for my brother, but also for the countless Catholics who have a profound, lifelong cognitive impairment. By circumstance, they cannot speak for themselves. I want to show that the Catholic moral tradition has a way to think about the properly human happiness and holiness of Christians who lack the use of reason. My hope is that a clear and concise description of Catholic teaching on these themes will encourage and support Christians whose lives are somehow shaped by the realities of cognitive impairment. Toward that end, the brief and incomplete remarks that follow aim to highlight some underappreciated aspects of Catholic teaching on our life in Christ, relevant to the creaturely dignity and grace-capacitated moral aptitude of my brother and persons like my brother.

My mother says “yes,” when I ask her if Vicente knows and loves God, if he follows Jesus, and if he does good and holy things (like pray, control his temper, repent, show mercy, worship, etc.). As St. Thomas Aquinas has helped me understand the moral teachings of the Catholic Church, I believe that the things my mother taught me to recognize are affirmed by some of the most basic and fundamental principles of Christian faith and hope. In other words, it is only when we underemphasize traditional Christian doctrine on what it means to be a human being and what God gives to the Church in the sacraments that profound cognitive impairment presents a problem or tension for Catholic moral teaching on the virtues.

The Dignity of the Image of God: Actual Knowledge and Actual Love of God

The starting point for every reflection on [mental impairment or mental] disability is rooted in the fundamental convictions of Christian anthropology: even when disabled persons are mentally impaired or when their sensory or intellectual capacity is damaged, they are fully human beings . . . independently of the conditions in which they live or of what they are able to express, [all human beings] have a unique dignity and a special value from the very beginning of their life until the moment of natural death.

—John Paul II, “On the Dignity and Rights of the Mentally Disabled Person”

Central to the traditional Catholic understanding of persons like my brother is the presumption that they are not exceptional—nothing about Vicente’s condition, strictly speaking, makes him “special.” That is to say, Vicente does not belong to any kind or class of beings other than the human species. Vicente is certainly a unique individual; however, like every other human being, the characteristics and qualities that distinguish him from other persons do not in any way change the kind of being that he is. In the ordinary way that Christians confess God as the Creator of humanity, God holds Vicente’s being in existence and relates to Vicente in the same way that God relates to each individual member of the human species. Christians have a term for that relationship: the image of God.

Theologians very often describe the human being as “the rational animal,” on the understanding that “reason” or “rationality” (the ability to abstract principles and connections from our sense experience) expresses something important and distinctive about human beings as the image of God. Properly understood and responsibly framed, that conceptual shorthand is useful and worth retaining. However, on the Christian view, our specific dignity is not founded in the biological potential for reason, the actual use of reason, or some other clever thing that our species can do (e.g., language, moral deliberation, abstraction, etc.). It is common sense, at least for Augustine and Aquinas, that the dignity of the image of God borne by the human being cannot be located in something transient like the use of reason—otherwise, we would cease to be human when we slept, and both infants “who are sunk in a vast and dark ignorance” and elders who “have lost the light of their eyes” would, at best, be only nominally human.

We should still affirm that the biological potential for reason and the actual use of reason are important manifestations of the determinative, permanent, and inviolable dignity of the human being as the image of God. However, what is important to understand about the Catholic view is that transient manifestations of our creaturely dignity are not the seat or foundation of our creaturely dignity as the image of God.

As far as we can tell, my brother Vicente lacks the use of reason. So, how do Catholics understand his inviolable dignity as an intellectual creature? The relationship between the creature and the Creator is where any coherently Christian discussion of human dignity must begin. Specifically, the personal and interpersonal dynamic between the image of God and God is central to traditional Christian anthropology, and it is rooted in the Christian understanding of the intimacy and love that unfolds in the communion of the Blessed Trinity.

Formed in the image of the triune God, as affirmed by the Second Vatican Council in Gaudium et Spes, the human person as a whole (body and spirit) is individually constituted in relationship with God, where the permanent nature of every particular person (as bearer of the image) consists in a living orientation or natural desire to know and love God (the source of the image). What this means is that the dignity of humanity is relationally constituted, from the first moment of our individual lives to the very last moment—consisting in desirous movement toward the truth and goodness of the One who formed us. This living activity of the whole person is exercised through an immaterial gift that all human beings have and that Aquinas calls “intellectual light,” which we could characterize as the ability of every human being to perceive and actually know the “traces of its Creator” as First Cause, through our sense experience of the world—on this view, even the most rudimentary sense experience of the world gives itself to knowledge and love of the Creator.

In their own way, both Augustine and Aquinas affirm that the dignity of the human being is rooted in each individual’s actual knowledge and love of God. Moreover, both Augustine and Aquinas affirm this understanding of the image of God in the course of explicit discussions of those who lack the use of reason. Specifically, for both Augustine and Aquinas, the fact that the dignity of the human being as the image of God includes the limitations of the body does not mean that the awareness and progress of any particular human being is reducible to the condition of the body.

Because this natural creaturely dignity involves the whole human person (body and spirit), our awareness of the Creator and our progress toward the Creator grow and unfold in and through the natural faculties of our bodies and according to the limitations of the body—i.e., we exist amid the contingencies and causal dynamics of time, space, matter, etc. These limitations are not a flaw; rather, these limitations are the condition of our freedom for growth and change. In fact, for Aquinas, the limitations of the body provide human beings with an opportunity that even the angels do not have: we have the time and the opportunity to open ourselves, to be wooed by God, and to direct ourselves toward the beauty of God’s goodness—to whatever extent we are able. With this freedom to choose the good, however, comes the possibility of failure.

Perfection and Sacramental Grace

Christian morality consists, in the simplicity of the Gospel, in following Jesus Christ, in abandoning oneself to him, in letting oneself be transformed by his grace and renewed by his mercy, gifts which come to us in the living communion of his Church . . . By the light of the Holy Spirit, the living essence of Christian morality can be understood by everyone, even the least learned, but particularly those who are able to preserve an “undivided heart.”

—John Paul II, Veritatis Splendor

In the ordinary way, like every other living person, Vicente exists in the unfolding drama of redemptive history. For Catholics, the moral lives of persons who lack the use of reason are understood primarily through their membership and participation in the Body of Christ. According to the Catholic view, Vicente is incapable of personal sin exactly to the extent that he lacks the use of reason. Nevertheless, like all human beings, Vicente bears the wounds of original sin in his body. The distinction between individual personal sin and the common wounds of original sin is central to the Catholic understanding of the ordinary vulnerability of the human body to damage, dysfunction, and decay.

I noted at the outset the Catholic presumption that severe intellectual disability does not disqualify a person from Christian Baptism, nor does it alienate a person from the grace and gifts conferred through the sacrament. In and through the sacrament of Baptism, each Christian is liberated from the bondage of original sin, incorporated into the Body of Christ, and given new life in Holy Spirit. The entirety of the Christian’s natural and supernatural life in Christ is rooted in the sanctifying grace of Christian Baptism and animated by the gifts of the Holy Spirit, which complete and perfect the virtue of those who are docile to the prompting of the Holy Spirit. The grace conferred by God through Baptism makes it possible for us as Christians to live in a way that fulfills the dignity of our created nature: we are given the virtues of faith, hope, and love (which enable or dispose the Christian for participation in the divine nature) and those dispositions are empowered (or actualized) for living and acting in accord with the Holy Spirit.

Disposed and moved by grace, the Christian is made free to perform good acts and grow in virtue. In Baptism, every Christian receives a vocation to progress toward the happiness of friendship with triune God, and every Christian is graced with the freedom to attain the holiness of virtuous participation (by knowledge and love) in the truth and goodness of the Holy Trinity.

The effects of Baptism are two-fold: the healing of the wounds of original sin and the restoration of relationship with God. In Baptism we are incorporated into the Body of Christ and we receive supernatural gifts. There is no question in the Code of Canon Law about the Baptism of those who lack the use of reason. Their Baptism is understood in a way that is analogous to the Baptism of infants. And there is nothing in Catholic teaching to suggest that the objective effects of Baptism are not obtained in the case of those who lack the use of reason. The presumption is that in and through the sacrament, grace makes possible a supernatural life by way of the infused virtues—and that this happens independent of a particular measure of occurrent awareness, as in the case of infants or those who lack the use of reason. There is nothing about the condition of a person with a profound cognitive impairment that would somehow exclude him or her from being brought into the communion of the Body of Christ.

Vicente was baptized as an infant. Through his Baptism, my brother is fully incorporated into the Body of Christ and he is recognized as a member of the Catholic Church. Based on our understanding of the effects of Baptism, what can we say about the moral lives of persons like my brother?

According to the Code of Canon Law, my brother is “regarded as an infant” to the extent that he “lacks the use of reason” and is “incapable of personal responsibility,” which means that my brother is “incapable of committing an offense” and that he cannot be held liable for any violation of ecclesiastical law or moral precept. However, because it is unclear if Vicente has attained the requisite “age of discretion” or “age of reason,” there is a question as to whether or not persons like my brother are capable of the basic understanding and devotion that is customarily associated with a person’s capacity to receive the grace conferred in the sacraments of Penance, Eucharist, Confirmation, and the Anointing of the Sick.

The Sacraments and Understanding

It is true that some basic understanding and recognitions are held forth as a precondition for any particular person’s ability to receive the grace conferred through the Eucharist and the Anointing of the Sick. With the Eucharist, for example, the Magisterium and the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops have entrusted the sacramental admittance of persons who lack the use of reason to the discretion of the local parish priests and the families of those Christians who lack the use of reason, instructing that questionable cases should be resolved in the favor of the right of the baptized person to receive the sacrament. That resolution in favor of the cognitively impaired person, however, is tuned to ensure that the Eucharist is administered to persons who simply cannot express their recognition of Christ’s Body and their internal disposition to receive the sacrament. If the Body of Christ is not recognized in the Eucharist, the consecrated host is consumed only as bread. Similarly, in the sacrament of Anointing, if a Christian does not desire that their affliction be joined with Christ, the rite has no effect.

However—and this is important—in the case of persons who lack the use of reason, Canon Law treats the Sacrament of Confirmation differently. Confirmation, as we read in the Catechism, “is necessary for the completion of baptismal grace . . . unites us more firmly with Christ . . . increases the gifts of the Holy Spirit in us . . . renders our bond with the Church more perfect . . . and gives us special strength” (§1302). The Catholic understanding of this sacrament provides a way for us to understand the moral life and moral potential of persons like my brother.

Can. 889 §1 Every baptised person who is not confirmed, and only such a person, is capable of receiving confirmation. §2 Apart from the danger of death, to receive confirmation lawfully a person who has the use of reason must be suitably instructed, properly disposed and able to renew the baptismal promises.

Can. 890 The faithful are bound to receive this sacrament at the proper time. Parents and pastors of souls, especially parish priests, are to see that the faithful are properly instructed to receive the sacrament and come to it at the opportune time.

Can. 891 The sacrament of confirmation is to be conferred on the faithful at about the age of discretion, unless the Episcopal Conference has decided on a different age, or there is a danger of death or, in the judgment of the minister, a grave reason suggests otherwise.

What we find in the standard Canon Law commentaries and the relevant episcopal guidelines is that the practical interpretation of these canons in the Rite of Confirmation allows exceptions to the recommended preparation for Confirmation: when death is immanent, with an infant for example, and in the case of those who lack the use of reason, even when there is no danger of death.

The Church’s teaching and the Church’s practice on the relationship between the use of reason and the perfection of human happiness in Confirmation are framed by the Catechism in a way that draws upon Aquinas. Presuming the grace of Baptism, Aquinas writes:

The intention of nature is that everyone born corporally, should come to perfect age [i.e., capable of performing “complete acts,” characterized by the freedom of deliberative self-movement]: yet this is sometimes hindered by reason of the corruptibility of the body, which is forestalled by death. But much more is it God’s intention to bring all things to perfection, since nature shares in this intention inasmuch as it reflects Him. . . . Now the soul, to which spiritual birth and perfect spiritual age belong, is immortal; and just as it can in old age attain to spiritual birth, so can it attain to perfect spiritual age in youth or childhood; because the various ages of the body do not affect the soul. Therefore this sacrament [Confirmation] should be given to all.

In other words, building upon Aquinas’ distinction between the age/perfectibility of the body and the age/perfectibility of the soul, the Catholic view is that, although the human intellect can be functionally debilitated or hindered in its act—for example, by brain lesion or physical immaturity— the intellectual soul is not essentially impaired or corrupted when the body is impaired or corrupted. Rather, any functional debility of the soul, coinciding with particular corporeal limitations (defectum) or weaknesses (infirmum) of the body, is an accidental constraint of immaterial operations. These immaterial operations, constrained as they are, can be elevated by the sacramental grace of Baptism and Confirmation to partake and grow in a contemplative happiness that exceeds our nature, in this life. John Paul II makes this clear: “When this body is gravely ill, totally incapacitated, and the person is almost incapable of living and acting, all the more so [does] interior maturity and spiritual greatness become evident.”

Virtue and Those Who Lack the Use of Reason

For [mentally] disabled people, as for any other human being, it is not important that they do what others do but that they do what is truly good for them, increasingly making the most of their talents and responding faithfully to their own human and supernatural vocation.

—John Paul II, “On the Dignity and Rights of the Mentally Disabled Person”

According to Aquinas, the intellectual powers of the human being are not in themselves weakened when the body becomes weak, because the soul, which is the living principle of these powers, is unchangeable. This is where Aquinas can help Catholics today understand the moral implications of Baptism and Confirmation when it comes to the moral life of those who lack the use of reason.

For Aquinas, the very structure of our constitution as composite creatures entails that our capacity to perceive, understand, and act requires the corruptible and contingent corporeal faculties of the body. This is how we realize our natural good. Likewise, for Aquinas, it belongs to the very structure of our constitution as composite creatures that the natural aptitude of the human being to be elevated and moved by grace is not wholly contingent upon the well-being of the body. Our ability to perceive, understand, and participate supernaturally in the imperfect happiness of this life, by way of our baptismal incorporation into Christ, cannot be destroyed by original sin or its corporeal wounds.

At Baptism, as with all the baptized, God imparts supernatural virtue to those who lack the use of reason. Although persons like my brother Vicente are hindered in their acquisition of moral virtues like prudence, in Baptism, his soul (like the souls of all Christians) was infused with a supernatural disposition for acts of virtue. The grace and impartation of virtue at Baptism—as well as the gifts of the Holy Spirit— cannot be rendered inoperative even in the profound case of one who absolutely does not have the use of reason due to a profound impairment of the cognitive faculties. Such a person lacks the ability to recognize ends and means, and, therefore, like a very young child, cannot exercise free will.

What makes Aquinas’ understanding of free will and voluntary action interesting in the case of those who lack the use of reason is that in Baptism, according to Aquinas, God not only imparts supernatural virtue, but God also moves the human being to action. God does this “not only by proposing the appetible to the senses, or by effecting a change in [the baptized person’s] body, but also by moving the will itself.”

Just as the acquired virtues dispose and enable a person to act in accordance with the light of natural reason, which is proportionate to human nature, in the light of grace, the infused virtues dispose and enable a person to act in a “higher manner” and toward “higher ends,” in relation to a “higher nature” which is our progress toward the perfect participation of the blessed in the divine nature.

For Aquinas, the virtue of those who lack the use of reason, as with all Christians, is not principally measured according to the rule of magnanimity. Rather, our virtue is measured for its likeness or conformation to Christ. And it is only on this christoformic basis that the effective grandness in potency and productivity of a moral act can bear the significance Christians call “holiness.”

So, what might this look like?

According to Aquinas, the consummation of grace (and the infusion of supernatural virtue at Baptism) can be understood to capacitate someone who completely lacks the use of reason with supernatural knowledge and a supernatural principle of self-movement. So capacitated, there is no reason to reject the possibility of a virtuous knowledge and love of God in the case of a person with a profound cognitive impairment.

The justice of the judge who discerns what is due and the justice of the child who shares her toy are both acts of justice. The gravity of the circumstances and the dignity of the end sought do not increase virtue qua virtue; what is increased is the magnificence of the act as an imitation of God’s knowledge and love. A person can be virtuous without having the full use of reason, provided that the person so afflicted acts in accordance with the goodness and truth that is understood—even if that understanding is infused knowledge.

Which is to say, it is possible that some of the most holy acts of knowledge and love in the sweep of redemptive history have been performed by “morons,” “imbeciles,” “retards,” “mental defectives,” and “feebleminded” persons—heroic acts of contemplative virtue, breathtaking in their christoformic purity and holiness. The conformation in virtue proportionate to the condition of a baptized adult who has a profound, lifelong cognitive impairment—might look like this:

The courage to go willingly (or to be taken) into strange and unknown places, trusting in the goodness of your mother. Allowing yourself to fall asleep even though you are unsure of where you are. Being open to a new experience, such as the texture of a new brand of diapers.

The justice of looking in the direction of your brother, even when you are angry with him—because he was gone for too long and you missed the sound of his voice.

Peacefully eating the food that is given to you, even if it is not your favorite.

The temperance of chewing slowly. Not grabbing food off the table. Not yelling when you are uncomfortable. The self-control required of one who understands that it is wrong to urinate while his diaper is being changed.

The prudence of knowing that some things are good and some things are bad. Loving what is good, and adjusting your actions in accordance with the good that is understood. For example, recognizing and enjoying the presence of children, or shaking your arms to the sound of country music.

It looks like a profoundly disabled man who has never had the full use of reason, sensing his brother’s voice and . . . nothing, or almost nothing. No (deliberative) understanding and no (reasoned) response. And, yet, because Vicente is an intellectual creature who bears a likeness unto God according to image; and because his natural aptitude for knowledge and love belongs to the immortal and incorruptible activity of his rational soul; and because he has been baptized in the faith of the Church, receiving the consummation that is grace, and a likeness in virtue through the infusion of faith, hope, and love; and because he understands with a knowledge that is not his own and loves by a principle of desire that is not his own—because of all this, according to Aquinas, his sensing is more than mere sense. Vicente’s sense experience, even if it is not fully understood and frightfully dim, is the experience of an intellectual creature. And, because he is baptized, his experience of his brother’s voice has a significance that is supernatural in character.

It might be friendship. Not the Aristotelian friendship between two “non-defectives”; not a thin caricature of intellectualist friendship; and not a notional friendship of “presence” offered by God through a soulless human body incapable of knowledge, love, or human happiness. Rather, the kind of friendship described by Aquinas in his Treatise on Charity, which is only possible for creatures endowed with an immortal and incorruptible rational soul—the substantial form of the human being, the image of God, and the seat of our natural aptitude for knowledge and love. It would be a friendship based on the fellowship of happiness, which is the consummation of grace, where our creaturely likeness to God precedes and causes a supernatural likeness that we share as members of the Body of Christ. In other words, by the loving-kindness of the Father, through the reconciling gift of Christ Jesus, and in the living fellowship of the Holy Spirit, a profoundly disabled man might recognize, by way of his brother’s voice, a friend.