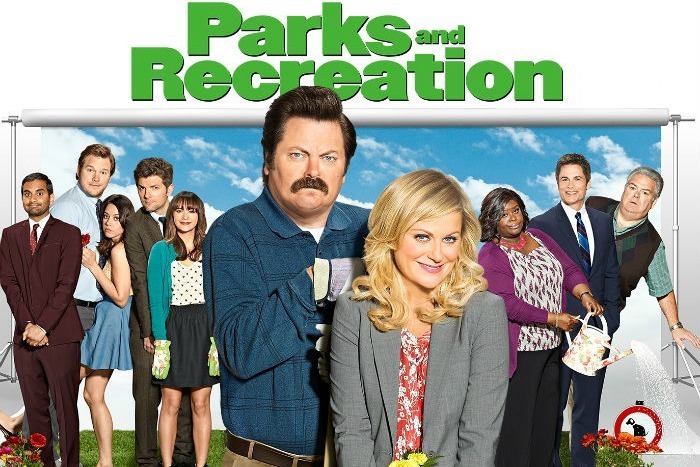

Over the past several months, I’ve been rewatching NBC’s comedy series Parks and Recreation, which is, in my opinion, one of the most quietly wonderful shows ever to be on television. Having seen every episode at least once now, I think I’ve figured out what made the show work so well (or, more accurately, what made it work so well once its writers figured out what they wanted it to be). Parks and Rec works because its characters are better together than they would be alone. Fans of the show undoubtedly recognize themselves in one or more of the characters (I’ve been cast as Leslie Knope by multiple friends, and I’ve cast my own friends as Ron Swansons, Donna Meagles, even April Ludgates), and it is this recognition that also serves as a reminder that we are made better human beings by the other people in our lives than we could ever become on our own.

Leslie’s overachieving drive and relentless enthusiasm needs to be tempered by Ron’s taciturnity, Ben’s pragmatism, and Ann’s steadiness. On the other hand, Ron’s reluctance and curmudgeonliness, loveable though it is, needs to be prodded on occasion by Leslie’s zeal, Andy’s innocent neediness, and Diane’s affectionate insistence. This analytical exercise could be done for every character on the show, because in the world of Pawnee, Indiana, no character is an island, and no character is a caricature. Chris Traeger, with all of his unbridled optimism, struggles with the dark realities of life and learns to rely less on his own sheer force of will and more on his friends (and his therapist Dr. Richard Nygard) to pull him through. Even April, with all of her darkness, loves Andy and Leslie and Ron and Champion (and even Ann) with a fierce loyalty, and she grows in her ability to love precisely as a result of her relationships.

What Parks and Rec teaches us is that, even as we remain true to ourselves, it is our friends and our community (which aren’t necessarily the same thing) who help us grow more fully into ourselves. Yes, Leslie will always be driven, Tom will always be entrepreneurial, Donna will always be mysterious and fabulous, April will always be morbid, Andy will always be “simple” (and “fine,” to quote Donna), Ben will always be nerdy, Chris will literally always be upbeat, Ann will always be nurturing, Jerry will always be the secret icon of the good life, and Ron will always be, well, Ron.

The genius of the show lies in the fact that these people almost always act in a way that the audience expects them to act, in a way that’s in keeping with who they are at their core. Yet, the even greater genius of the show is that, even in the midst of that predictability, there is still room for growth: its writers created incredibly specific characters and kept them interesting throughout seven seasons precisely by cultivating the characters’ relationships with one another in both expected and unexpected combinations. We can predict how Tom and Donna will act together, but what would happen if you put Jerry and Donna in a room together? Or Jerry and Ben? How can Donna and April grow as individuals and as friends? What about Ron and Ann? Or April and Ann? By bringing together characters whose traits are complimentary (Leslie and Ben, Donna and Tom), the writers show us who these people are at their most comfortable. By bringing together characters whose traits seem to be more like like oil and water (Leslie and Ron, Tom and Ben, April and Ann), the writers show us how these people can help one another to grow in patience, forgiveness, empathy, understanding, even love.

Moreover, the reappearance of so many unbelievably memorable minor characters throughout the show—Joan Callamezzo, Perd Hapley, Jean-Ralphio and Mona Lisa Saperstein, Shawna Malwae-Tweep, Ethel Beavers, Bobby Newport, all of the Tammys, Jeremy Jamm, even unnamed citizens of Pawnee who consistently show up to town hall meetings and complain about the same things over and over (like the guy who always starts chanting)—shows us that we are called to be in a relationship of some form with everyone whom we encounter.

One can contrast the Parks and Rec approach with that employed by other ensemble comedies like Friends: absent the presence of supporting and minor characters whose purpose is to broaden the horizons of the series regulars, challenging them to grow into and beyond themselves, the central characters devolved over ten seasons into mere caricatures because their community was too insular, too enclosed, too self-involved. The same could be said for Community and even Seinfeld, resulting in varying degrees of absurdity and implausibility that, while entertaining, never challenge the viewers themselves to any personal growth either.

At its heart, Parks and Rec is an icon of true community that can inspire its viewers to become better people by opening themselves up to and learning to love others. Throughout any given day, we interact with people whom we like and whom we do not like, people whom we know well and people whom we do not know well or even people whom we do not know at all. Whether these interactions take place with the series regulars in our lives, or the special guest stars, or even the extras in the background, for the Christian living as a member of the Body of Christ, we are called to approach each and every interaction within our particular communities with the love of Christ. We won’t always succeed in this, but if our successes outnumber our failures, then we, like our Parks and Rec doppelgängers, will continue to grow into more complete versions of who we already are; in other words, we will grow into more faithful versions of who God has called us to be.