The wolf also shall dwell with the lamb, and the leopard shall lie down with the kid; and the calf and the young lion and the fatling together; and a little child shall lead them.

—Isaiah 11:6For to those who have, more will be given; and from those who have nothing,

even what they have will be taken away.

—Mark 4:25

+

SPOILERS AHEAD . . .

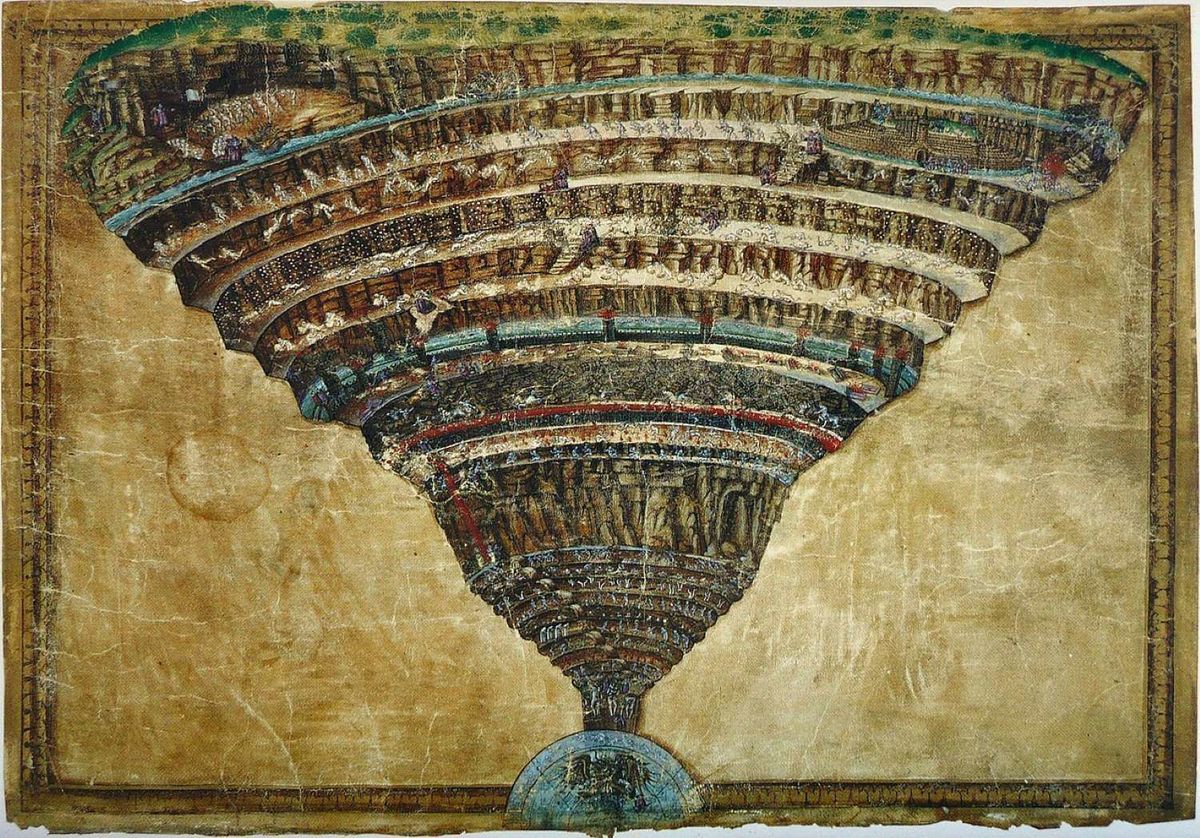

Cormac McCarthy’s The Road can be read as a severe and precipitously hopeful re-telling of Dante’s Comedy. This comes clear right from the novel’s opening lines, which echo the opening lines of the poem:

When he woke in the woods in the dark and the cold of the night he'd reach out to touch the child sleeping beside him. Nights dark beyond darkness and the days more gray each one than what had gone before. Like the onset of some cold glaucoma dimming away the world.[1]

Surrounded by cold and dark, the man remembers a dream in which he had “wandered in a cave where the child led him by the hand.”[2] Wandering, he and the boy, “like pilgrims in a fable swallowed up and lost among the inward parts of some granitic beast,” found themselves at last on the shore of a vast subterranean lake; across the water, a creature appeared, “pale and naked and translucent,” until, startled by their presence, it broke into the dark.[3]

The parallels to Inferno are unmistakable:

Half way along the road we have to go,

I found myself obscured in a great forest,

Bewildered, and I knew I had lost the way (Inferno I.1-3).[4]

In the poem’s opening stanzas, Dante, like the nameless father in the novel, finds himself beside “dangerous water.” He too sees a beast, although he does not startle it away. In fact, he sees three beasts—first, a leopard, a “wild animal with brilliant skin,” then a lion, and, last, a she-wolf—each of which startles him and then forces him back to the road he has forsaken. And he follows a guide—not a child, a father: the Roman poet, Virgil, who appears after the beasts have blocked the way—into the dark and down into the maw of hell.

The novel’s closing lines mirror the poem’s closing lines, as well. Dante, leaving Beatrice, as before he had left Virgil, comes at last into the living, eternal light:

In the profundity of the clear substance

Of the deep light, appeared to me three circles

Of three colors and equal circumferenceAnd the first seems to be reflected by the second,

As a rainbow, and the third

Seemed like a flame breathed equally from both (Paradiso XXXIII.115-121).

Within the shape of the circles, Dante sees an image of one “painted with our effigy.” And “like a geometer who sets himself/to square the circle,” he fails to find words for what he sees. He loses his imaginative and linguistic grip on reality. Rapt in mystery, his will and desire are “turned like a wheel, all at one speed, / by the love which moves the sun and the other stars” (Paradiso XXXIII.144-145).

The novel’s last lines, like the poem’s, give us the story of a salvation. But in McCarthy’s cosmology, heaven, hell, and purgatory overlap, coinhere, and interpenetrate; therefore, the father and son are saved not at the apex of an ascent following a descent, but in a movement that is cruciform: all-at-once vertical and horizontal, inward and outward. McCarthy’s salvation requires a separation, a turning, or series of turnings, as Dante’s does. But the son does not turn from humans to God, but from his father to a new mother—a Mary who both receives him and returns him to his father. Christ-like, the child finds God not in turning away from others toward eternity but in turning toward them in time—both the living (his new family) and the dead (his old family).

+

Scholars disagree about whether or not The Road’s ending is nihilistic or existential, meaningless or mystically paradoxical. Certainly, the story is dark, and ends darkly. And the coda that comes at the end of the story is darker still. But it is hard, if not impossible, to tell if it thrusts its readers into the blank dark of despair and disconsolation, or envelops them in the luminous dark of mystery and consolation:

Once there were brook trout in the streams in the mountains. You could see them standing in the amber current where the white edges of their fins wimpled softly in the flow. They smelled of moss in your hand. Polished and muscular and torsional. On their backs were vermiculate patterns that were maps of the world in its becoming. Maps and mazes. Of a thing which could not be put back. Not be made right again. In the deep glens where they lived all things were older than man and they hummed of mystery.[5]

Leaving Beatrice, beholding God, Dante sees humanity’s likeness etched into the divine shape. But McCarthy’s narrator, moved by the story he has told, sees other likenesses, other shapes. At the end of his story—indeed, after the end—he is returned to the beginning of all things. He sees the becomings of the world etched (map-like or maze-like) on the shimmering backs of the now-disappeared mountain trout. It seems, then, the narrator’s reflection turns him away from humans without quite turning him to God. If the Paradiso ends in a light too bright for vision, The Road ends, or appears to end, in a darkness in which there is no light at all, a darkness with no gleams of turning. The Road can be read, then, as “a story about the end of the world in which the world ends.”[6] And the coda can be heard as an elegy.[7] Or, more threateningly, it can be read as the boy’s wishful dream.[8]

On such readings, the man (and perhaps also his son) has fallen into something like Kierkegaardian despair. The coda, so read, presses the reader toward the same desolation. Despair, for Kierkegaard, names a misrelation, a misrelating, of a person to himself. If a man wants not to be the self he has been given to be; if he wants instead to be a self he has dreamed up for himself; if he has no choice but to be the self he does not want to be; at that point, he is left in despair. In Kierkegaard’s own words: “to despair over oneself, in despair to will to be rid of oneself—that is the formula for all despair.”[9] It is worth asking, then, if the father suffers this sickness unto death. Does the narrator? Do we?

It might seem so. Not long before he meets his end, the man sees—or, perhaps, foresees—“the absolute truth of the world.” He catches sight not of “three circles / Of three colors and equal circumference,” as Dante does in his final vision, but of “the cold relentless circling of the intestate earth.”[10] He sees not the wheel of divine and angelic providence, but “the blind dogs of the sun in their running.”[11] Not a light from which it is impossible to turn away, but the “crushing black vacuum of the universe.”[12] And, unlike the Beatrice-led Dante, he finds himself finally facing not light, but darkness: “Darkness implacable.”[13]

Living like beasts, hunted night to night, “from dark to dark,” the man and the child live on “borrowed time [in a] borrowed world [with] borrowed eyes with which to sorrow it.”[14] A startling turn of phrase, “borrowed,” which reveals some aspect of the man’s imagined relation to a “God” who neither exists nor does not exist, who does not give but only lends and exacts from those who borrow. Father and son, living like “two hunted animals trembling like ground-foxes in their cover,” receive everything they need to endure a world they can only suffer, even in moments of good fortune and joy. It is said, “The rich ruleth over the poor, and the borrower is servant to the lender” (Prov 22:7).

His vision of the world’s supposed truth suggests that the man’s misrelating to God has left him rotting, dimming, shrinking. Still, he is not quite in despair. Even misrelating to God, after all, is a form of relating—a peculiar and awkward, but no less authentic, profile of devotion. The man, to be sure, does not know what to make of God as Father—God understood as Creator and Sovereign, the source and supervening order of all that exists. But he does in some sense trust God as Son—God understood as companion and guide, as can be seen in the way he relates to his own son as a father. He not only cares for his son; he believes in him. And that belief, in the end, opens him up to salvation, or something not entirely unlike it.

+

At the very beginning of the story, just after waking from his nightmarish dream, the man confesses to himself of his son, “If he is not the word of God God never spoke.”[15] Later, fireside, having washed a dead man’s brains from his boy’s hair, he wraps his boy in a blanket, holding him close and tousling his hair to dry it, an act he regards as “some ancient anointing.” In that tender moment, he again confesses his belief in his only begotten: “Golden chalice, good to house a god.”[16] And recognizing his son as the Grail, the father lifts—or lets slip—a prayer to the Father: “Please don’t tell me how a story ends.”[17]

These affirmations are critical, because they suggest that the father’s trust in his son is neither sentimental nor conjured from nothing. He is not speaking “sweet nothings”; he is professing, confessing. And he does so because there is, in fact, something eccentric and mystifying about this child, something which in spite of everything recurrently elicits the father’s belief in him as something like an incarnation of the second coming.[18] What McCarthy describes for us is not simply a father adoring his imperiled child; we are given the vision of a vision, allowed to glimpse the father’s witness to his son’s transfiguration.

Early in the journey, for example, the man steps away from the camp, and looking back, he is surprised to see “the tarp was lit from within where the boy had wakened.” Against the darkness, he notices how “the frail blue shape of it looked like the pitch of some last venture at the edge of the world. Something all but unaccountable. And so it was.”[19] He realizes in that moment that this unaccountable light, shining out from the tabernacle he had made, is the source of a last hope against all hope, not only ventured at the end of the world but hazarded as the end of the world. This is why McCarthy says their journey brought them to “the point of no return,” a point “measured from the first solely by the light they carried with them.”[20] The son, not only a bearer of the light, but one with its source, is the end of the end of all things. Thus, the father and the son make the road a way by walking it.

McCarthy takes pains to show that the light not only rests upon the boy but emanates from him. “When he moved the light moved with him.”[21] In the middle of the journey, when the boy asks if the “fire” they’re carrying is real, the father answers: “It’s inside you. It was always there. I can see it.”[22] And near the end, the father laments that “the salitter”—Boehme’s term for the divine substance; a favored metaphor for God’s fiery, explosive essence, the ultimate matrix of all influences, “the embodiment of the total force of the deity, the compendium of all forces operating in nature”[23]—is “drying from the face of the earth.”[24] He sees the world as Sodom: “flooded cities burned to the waterline.” But he also sees his son, the light originating from him, and so holds to hope:

He'd stop and lean on the cart and the boy would go on and then stop and look back and he would raise his weeping eyes and see him standing there in the road looking back at him from some unimaginable future, glowing in that waste like a tabernacle.[25]

In these epiphanies, the father learns the boy is not only his son. He comes to his son from the past, as it were, and so is bound to him as all fathers are bound to their sons. But the boy comes to him from the future, and so frees his father from the hopelessness of historical succession and perdurance.

As he lays dying, uncovered because “he wanted to be able to see,” the father makes his last confession: “Look around you, he said. There is no prophet in the earth’s long chronicle who’s not honored here today. Whatever form you spoke of you were right.”[26] Ely, a disfiguration of the biblical Eli, the child Samuel’s blind guide, proclaimed on the road: “There is no God and we are his prophets.” But the father knows, or learns, that there is a prophet, and he is God.

Allen Josephs draws attention to the fire and light motifs in the novel, arguing McCarthy intends them as evidences of “the boy’s sacred nature.”[27] Josephs sees these intimations of divinity—that is, figurations of Christ-likeness—not only in what the narrator and father say of the boy, but also in what the boy says of himself. At one point, for example, the father admonishes him for his compassion toward a thief. And the boy in response testifies of himself, asserting his awareness of messianic responsibility.

He’s not gone, the boy said. He looked up. His face streaked with soot. He’s not.

What do you want to do?

Just help him, Papa. Just help him.

The man back looked up the road.

He was just hungry, Papa. He’s going to die.

He’s going to die anyway.

He’s so scared, Papa.

The man squatted and looked at him. I’m scared, he said. Do you understand? I’m scared.

The boy didn’t answer. He just sat there with his head bowed, sobbing.

You’re not the one who has to worry about everything.

The boy said something but he couldn’t understand him. What? he said.

He looked up, his wet and grimy face. Yes I am, he said. I am the one.[28]

“I am the one.” As Josephs observes, the boy not only offers to take responsibility, “he offers to do so in unmistakably religions language,” echoing Jesus’s own self-attestation as the “I Am.”[29]

+

At the end, as at the beginning, the man awakes in the darkness and listens for his son:

He woke in the darkness, coughing softly. He lay listening. The boy sat by the fire wrapped in a blanket watching him. Drip of water. A fading light. Old dreams encroached upon the waking world. The dripping was in the cave. The light was a candle which the boy bore in a ringstick of beaten copper. The wax spattered on the stones. Tracks of unknown creatures in the mortified loess.[30]

He knows he is dying. The boy asks him about the child they had seen not too long before:

Do you remember that little boy, Papa?

Yes. I remember him.

Do you think that he’s all right that little boy?

Oh yes. I think he’s all right.

Do you think he was lost?

No. I dont think he was lost.

I’m scared that he was lost.

I think he’s all right.

But who will find him if he’s lost?

Goodness will find the little boy. It always has. It will again.[31]

“It will again.” These are the father’s parting words, a prayer as much as a promise, spoken as much to himself as to his son. And, crucially, spoken not about his son, but about another child, a stranger. Dying, returning all that he has borrowed, he sees at last how he has been enriched beyond imagination, and so is freed to regard someone else’s son as he had always regarded his own. He speaks of goodness finding the little boy. That he can speak in that way reveals that goodness has at last caught up to him.

After the father dies in the dark, the son stays by his cold body, saying his name. Then, after three days, the boy walks back to the road and looks along it. Like Moses on the mountain of God, he looks “back the way they had come.” He sees someone coming. His father had always said only enemies were behind them, yet the son does not run from the road. Instead, he stands his ground and waits, pistol in hand. And when the stranger arrives, the boy finds after a few words that the new man is one of the good guys. He also carries the fire. In their camp, he also finds that this man and his wife—a most unlikely holy family—have rescued the forsaken child he had so often worried about. The son’s future is assured by this surprising justification of his father’s last hope.

In the book’s closing scene, the woman puts her arms around the boy, draws him close, comforts him. “Oh, she said, I am so glad to see you.”[32] In the days that follow, she talks to him about God, and encourages him to pray. When he admits he cannot quite bring himself to do it, she assures him it is no failure. “She said that the breath of God was his breath yet though it pass from man to man through all of time.”[33] This is the last line of the story, and it reveals his father’s mistake: breath is not so much borrowed as shared. And so, after his father’s death, the son, thanks to a new mother, receives his father again as the Father. In this prayer, McCarthy presents us not with a flattening of transcendence into the existential, nor a reducing of God to the metaphor for those ties that bind us even to the dead. Instead, he reminds us how our relation to others is always also a relation to God in whom they exist in all their glorious and inviolable peculiarity.

+

Finally, the story leaves the boy with his new mother and their family and the narrator offers the dark coda: “Once there were brook trout in the streams in the mountains…” The story’s last word is a word about time. With that opening “Once,” the coda returns to time’s very beginnings, its primeval, pre-historical becomings, first acknowledging that all things in their density and irregularity were from the first mapped and mazed, deliberate and marvelous (“amazing” in the strictest sense), then elegizing what has been or shall be lost for good. There is “a thing,” “older than man,” the narrator says, that cannot be “put back,” cannot be “made right again.” It is this readiness to accept loss that distinguishes McCarthy’s hopefulness from mere sentimentality or wishful thinking. He does not indulge himself with thoughts of bliss in the afterlife or fantasize the return of the past.[34] He simply acknowledges that at their source, all things “hummed of mystery.”[35] And in that acknowledgement, he hints, slyly, that the hum of this mystery may not cease with the loss of this world or the death of the last living thing.

Cyril O’Regan, in an essay on Blood Meridian, concludes, somewhat reluctantly, that in McCarthy’s oeuvre “it is not clear that we have found the language in which to express an end to violence without end.” What is clear, however, is that for McCarthy, at least, “Christianity supplies neither its grammar nor its vocabulary.” But the reading I have offered suggests otherwise: Christianity, or at least its belief in Christ as the Word become flesh, the light which is the life of all tabernacling among us, witnesses to a working mystery always deeper than words, and deeper than the silence that comes before and after those words. For McCarthy, then, or at least for this story, that ineradicable mystery works in the last word, and the first. Or, better, it works not only the first and last word, but is itself the work of the Word that comes before and after the first and last word and the silence that seals them. Thus, the living in McCarthy’s worlds are not kept from dying, or secured against loss. Just the opposite, in fact. They suffer immeasurably, unendingly, from first to last. Still, for McCarthy, as for Dante, life, however shadowed, hums with mystery, because it is moved, secretly, by a fiery goodness as inextinguishable as it is inexplicable. And the gospel promised nothing else. Jesus said we will be left with nothing in the end. But because God creates from nothing, even that—indeed, only that—will be taken from us.

[1] Cormac McCarthy, The Road (New York: Knopf, 2006), 3.

[2] This beginning recalls the very end of McCarthy’s previous novel, No Country for Old Men ([New York: Vintage, 2006], 308-309), which closes with Sheriff Tom Bell remembering his father and his dreams about his father, the last of which involves meeting his father in a wintery mountain pass: “It was cold and there was snow on the ground and he rode past me and kept on goin. Never said nothin. He just rode on past and he had this blanket wrapped around him and he had his head down and when he rode past I seen he was carryin fire in a horn the way people used to do and I could see the horn from the light inside of it. About the color of the moon. And in the dream I knew that he was goin on ahead and that he was fixin to make afire somewhere out there in all that dark and all that cold and I knew that whenever I got there he would be there. And then I woke up.”

[3] McCarthy, The Road, 3.

[4] Dante Alighieri, The Divine Comedy; translated by C.H. Sisson (Oxford: OUP, 1998), 47.

[5] McCarthy, The Road, 241. The novel’s coda recalls, and in some way reaffirms, the epilogue at the close of Blood Meridian (New York: Vintage, 1998), which challenges, obliquely, the Judge’s claims to eternality. Hope is no more than a spark from “the rock which God has put there,” but the still small voice of sequence and causality and their validation in the predictability that makes possible even the most modest work (such as digging holes).

[6] John Clute, “End of the Road,” Science Fiction Weekly 497 (30 October 2006), n.p.

[7] David Huebert, “Eating and Mourning the Corpse of the World: Ecological Cannibalism and Elegiac Protomourning in Cormac McCarthy’s The Road,” The Cormac McCarthy Journal 15.1 (2017), 66-87. Allen Josephs (“What’s at the End of The Road?” South Atlantic Review 74.3 [Summer 2009], 20-30) argues that the coda is “cryptic,” intended to raise more questions than answers. It is not even clear, he believes, who is speaking to whom: “Is the narrator addressing the reader directly? Or is that second-person pronoun directed at the narrator himself, like a rhetorical question? Or is there an intentional conflation of narrator and reader and even ghosts?”

[8] Jacob M. Powning, “‘Dreams So Rich in Color: How Else Would Death Call You?’: An Exploration of the Ending of Cormac McCarthy’s The Road,” The Cormac McCarthy Journal 18.1 (2020), 26-36.

[9] Søren Kierkegaard, The Sickness unto Death (Princeton: PUP, 1980), 20.

[10] McCarthy, The Road, 110.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid., 4.

[16] In early drafts, McCarthy’s working title for the novel was The Grail.

[17] McCarthy, The Road, 74.

[18] Allen Josephs, “The Quest for God in The Road,” in Steven Frye, The Cambridge Companion to Cormac McCarthy (Cambridge: CUP, 2013), 133-146 (138).

[19] McCarthy, The Road, 41.

[20] Ibid., 236.

[21] Ibid., 277.

[22] Ibid., 278-279.

[23] Lawrence M. Principe and Andrew Weeks, “Jacob Boheme’s Divine Substance Salitter: its Nature, Origin, and Relationship to Seventeenth Century Scientific Theories,” The British Journal for the History of Science 22 (1989), 53-61 (53). See also: Ferdinand Christian Baur, History of Christian Dogma (Oxford: OUP, 2014), 298.

[24] McCarthy, The Road, 261.

[25] Ibid., 230. Emphasis added.

[26] Ibid., 277.

[27] Josephs, “What’s at the End of the Road?,” 25.

[28] McCarthy, The Road, 259.

[29] Josephs, “What’s at the End of the Road?,” 25.

[30] McCarthy, The Road, 236.

[31] Ibid., 236.`

[32] McCarthy, The Road, 286.

[33] McCarthy, The Road, 286.

[34] Huebert, “Eating and Mourning the Corpse of the World,” 80.

[35] McCarthy, The Road, 287. Interestingly, in Dante’s Divine Comedy there is a river in hell “…falling into the next circle/ Like the hum which bees make around a hive” (Inferno XVI.3), and in the empyrean, angels hum around the rose of the divine love like bees (Paradiso XXXI.7), perhaps another indication that McCarthy’s cosmology binds heaven to hell purgatorially.