In 1953, while The Lord of the Rings was being prepared for publication, Tolkien wrote:

The Lord of the Rings is of course a fundamentally religious and Catholic work; unconsciously so at first, but consciously in the revision. That is why I have not put in, or have cut out, practically all references to anything like “religion,” to cults or practices, in the imaginary world. For the religious element is absorbed into the story and the symbolism. However that is very clumsily put, and sounds more self-important than I feel. For as a matter of fact, I have consciously planned very little; and should chiefly be grateful for having been brought up (since I was eight) in a Faith that has nourished me and taught me all the little that I know.

The “of course” is very interesting: of course his epic work is religious and Catholic. It seems natural and obvious to Tolkien that it should be so. The Lord of the Rings, he says, is not superficially religious and Catholic but fundamentally so—at its roots, in its essence. This religious and Catholic element, however, “is absorbed into the story and symbolism,” woven into the warp and woof of the text, implicit, indirect. It was not “consciously planned”; that is to say, The Lord of the Rings is not an allegory of the Gospels or a tale didactically expressing Christianity. Rather, the whole world of Middle-earth and everything in it is infused with, rooted in, its author’s Christian vision of reality. And he says that this rootedness, this unplanned but essential quality to his work, comes about because he has been raised and nourished in the Catholic faith.

Commenting elsewhere on the inspirations for The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien noted that “on a lower plane: my linguistic interest is the most powerful force.” What, then, was on a higher plane? He explains, “If I may say so, with humility, the Christian religion (which I profess) is far the most powerful ultimate source.”

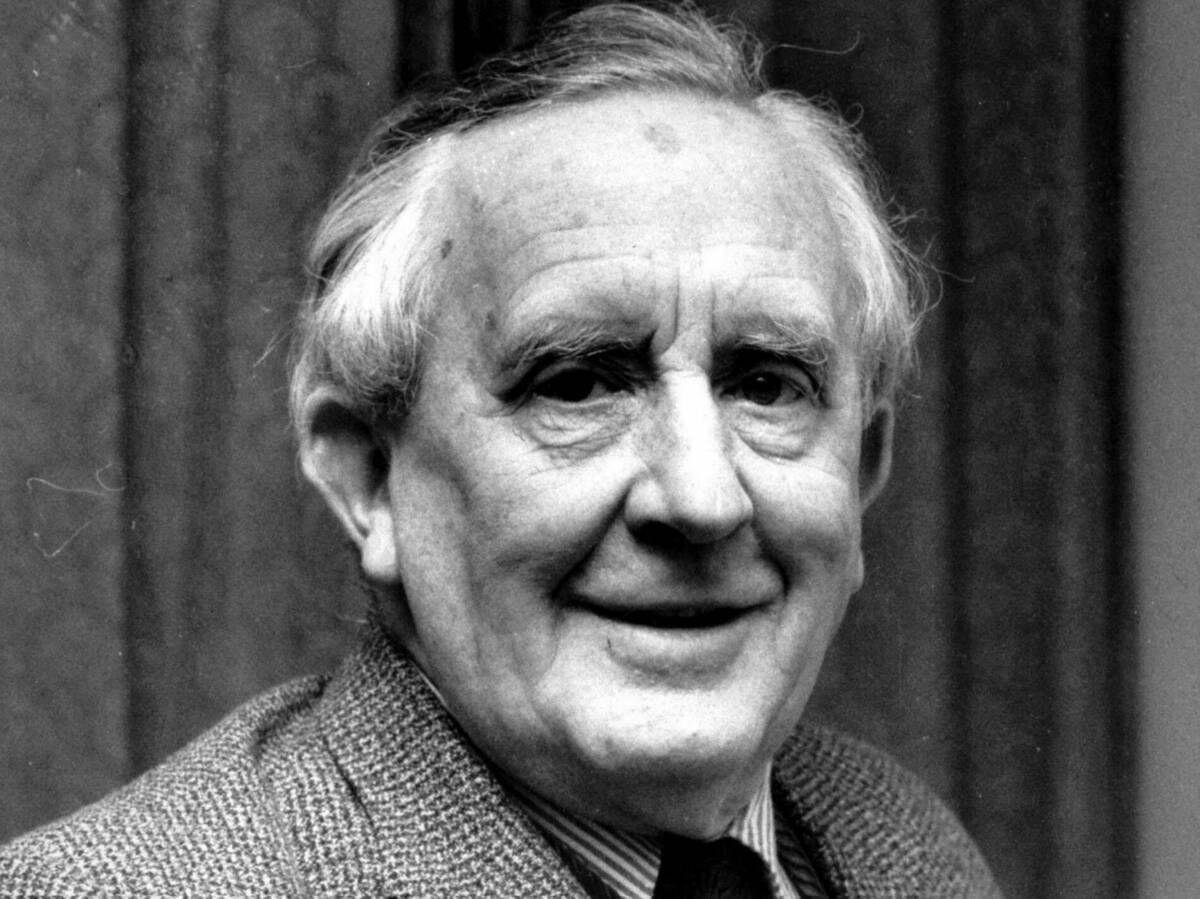

Tolkien’s faith was lifelong and deep. He was a committed Christian. To put a complex thing very simply, his faith was in Jesus Christ. He was not shy about this, frankly declaring his religious identity in various letters and interviews: “I am a Christian, and indeed a Roman Catholic”; “I am in any case myself a Christian”; “I am a Christian (which can be deduced from my stories).”

Which can be deduced from my stories. This statement is highly intriguing. Tolkien was always emphatic that his writings could not be read as simple allegories. As he remarked rather tartly, The Lord of the Rings “is not ‘about’ anything but itself. Certainly it has no allegorical intentions, general, particular, or topical, moral, religious, or political.” In this story, he said, “I neither preach nor teach.” Furthermore, his tales of Middle-earth are loved by millions of readers who are not Christian and may have little or no awareness of Tolkien’s own religious identity. If his faith can be “deduced” from his stories, the deduction is evidently not one that is easily arrived at.

What are we to make of this? How are we to understand the relationship between his faith and his fiction? My book, Tolkien's Faith, attempts to address that question biographically. In other words, it focuses on Tolkien’s life—his life of faith—in order to provide context for his works. Once we have a secure grasp of his spiritual identity, we will be able to gain a richer, deeper, more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of his writings—and their fundamental but implicit religious dimension.

A Life of Faith

There has been, to date, no full biographical treatment that presents Tolkien’s faith in detail. As a result, it has been all too easy simply to overlook the significance of his religious life, to allow unexamined historical or cultural assumptions to color our view of it, or to view it as a purely private expression of his personality.

Without even realizing it, we can end up taking Tolkien as a sort of cardboard Catholic, viewing his faith as a generic, static background to the supposedly more interesting and dynamic aspects of his life. Alternatively, we can regard him as a plaster saint to be put on a pedestal, someone whose religious life was ideal and equable. But his faith was not made of cardboard or plaster; it was neither boring nor easy.

As we look back on his completed life, it may seem inevitable or obvious that he could declare to an interviewer, “I’m a Roman Catholic. Devout Roman Catholic,” but in fact Tolkien’s faith was hard-won. His spiritual biography was one of drama and difficulty. In what follows, we will see that, although Tolkien was introduced to the Catholic faith by his beloved mother, Mabel, he also had many reasons to relinquish it and return to the Anglican church in which he had been baptized. As a young man, his experience of thwarted love could have embittered him against the Catholic priest who was his guardian. He fought on the front lines of the Great War, a conflagration in which most of his close friends were killed, and which caused some of the finest writers of his generation to abandon their Christian faith entirely. In a time when the Church of England’s status as the Establishment religion meant a great deal and Catholics were a socially disadvantaged minority, it would have made his career, his social life, and even his marriage smoother if he had muted his Catholicism or exchanged it for something more conventional. The experience of a second World War, this time with his own sons serving in the armed forces, could have caused him finally to abandon his faith altogether. The turmoil caused by Vatican II, and the loss of the Latin liturgy of the Mass that he loved so much, could have caused him to reject the authority of the Church or withdraw from engagement in Catholic life.

But he did none of these things: his convictions grew stronger and deeper even as he lived through fresh opportunities to set them aside. And, as we will see, this process of spiritual growth wasn’t easy. He went through a barren patch as an undergraduate and later a years-long stretch when, by his own account, he “almost ceased to practise” his religion. A full treatment of his faith uncovers a life marked by determination and decision.

This full treatment is important because Tolkien’s spirituality was central to his identity, as his family and friends constantly attest. His daughter, Priscilla, remembers him as “a devout Christian” with “a strong religious faith”; “he cared deeply about his religious faith.” His son John says that his faith “pervaded all his thinking and beliefs and everything else. . . . he was very much, always a Christian.” His nephew Julian recalls his uncle’s “strong faith” and “strong Christian principles.” His grandchildren concur: Simon describes him as “a devout Roman Catholic”; Joanna refers to “his profound belief in God”; Michael George notes that “my grandfather had a deep and nourishing faith.”

His friend Robert Havard described “the depth of feeling behind his Roman Catholic religious convictions.” The chaplain who attended Tolkien during a hospital stay late in his life stated that “he was a committed Christian and a committed Catholic, and his faith meant everything to him. His faith came from the core of his being.” Fr. Martin D’Arcy, one of the most notable English Jesuits of the twentieth century and an Oxford colleague, called Tolkien “a very good Catholic.”

Clearly, then, Tolkien’s faith was an essential part of his life and how he viewed the world: it shaped what he valued, the choices he made, and how he related with other people. Even if it were for that reason alone, an account of his religious commitments and practices is of interest to readers of his stories, or at least to those readers who want to gain a fuller picture of the man who could create such powerful and memorable works. It mattered to him, and that is a good reason for it to matter to us.

“Impossible to Disentangle”

But it also matters if we wish to have a deeper understanding of Tolkien’s creative output. Tolkien explained that there is “a scale of significance” in the types of facts that are relevant to understanding a writer’s work. In his own case, these facts include—at the bottom of the scale—his preference for certain languages over others. Other facts, he says, “however drily expressed, are really significant,” such as his rural childhood before the age of the machine. But then he goes on to say, “More important, I am a Christian.” We know that his linguistic interests and his early life in a Worcestershire village were indeed imaginatively formative: to note one influence is not to deny another. But by Tolkien’s own reckoning, his faith was more important for understanding his writings than either of these.

The world of Middle-earth is not a religious allegory. But that is not to say it is unconnected to the Christian religion that Tolkien actually believed in. In fact, he could get a bit testy when interviewers missed this point. “Of course God is in The Lord of the Rings. The period was pre-Christian, but it was a monotheistic world.” The interviewer asked, “Monotheistic? Then who was the One God of Middle-earth?” Tolkien, taken aback, replied: “The one, of course! The book is about the world that God created—the actual world of this planet.”

Tolkien once described The Lord of the Rings as “an exemplary legend. But this sounds dreadfully priggish when said.” The reason that he feared it sounded priggish (overly moralistic) was that “exemplary” literally means setting a good example for others to follow. He elaborates on this point elsewhere, saying that one of his aims in writing The Lord of the Rings was “the elucidation of truth, and the encouragement of good morals in this real world, by the ancient device of exemplifying them in unfamiliar embodiments, that may tend to ‘bring them home.’” It is important to do so because unless one’s understanding of “truth” and “morals” is integrated into day-to-day life, it remains abstract and irrelevant. This is a point that Tolkien’s friend C.S. Lewis brought out in his book Letters to Malcolm: Chiefly on Prayer, where he writes that “there is danger in the very concept of religion”:

It carries the suggestion that [religion] is one more department of life, an extra department added to the economic, the social, the intellectual, the recreational, and all the rest. But that whose claims are infinite can have no standing as a department. Either it is an illusion or else our whole life falls under it. We have no non-religious activities; only religious and irreligious.

Tolkien did not compartmentalize his faith. A repeated theme in the recollections of those who knew him is how integral his faith was with his whole person; it manifested itself in a natural manner and was not put forward awkwardly or ostentatiously. His friend Havard noted that his convictions were “apparent . . . but never paraded.” The hospital chaplain remarked, “he didn’t lay it on the counter for you and say, ‘that’s it, boys.’ But you knew that all the glory that he had meant nothing except his faith.” Clyde Kilby, who assisted him with his work on the Silmarillion, could recall “not a single visit I made to Tolkien’s home in which the conversation did not at some point fall easily into a discussion of religion, or rather Christianity. He told me that he had many times been given a story as an answer to prayer.” Kilby added that he had been struck by the naturalness of Tolkien’s faith: “He would just fling out these things: talking on the phone with a priest friend, I heard him say at the end of a conversation, ‘Well, may the Lord bless you’ in the most sincere feeling tone.”

Tolkien admitted that at times he did not live his faith as he felt he ought to, but it was never just one activity out of many in his very busy life. To understand this is to grasp a key insight into Tolkien’s personality and his creative process.

He once remarked that he found it “impossible to disentangle” faith and art. In his important essay “On Fairy-stories,” he declared that the writing of fantasy (and by extension, all literary creation) is “a natural human activity . . . a human right.” This conviction was based on his belief that human beings have been made in the image and likeness of God, and since God is creative, we would be less than human if we were not to express that side of our nature: as Tolkien put it, “We make in our measure and in our derivative mode, because we are made: and not only made, but made in the image and likeness of a Maker.” As Clyde Kilby recalled, “He believed that creativity itself is a gift of God.”

Art will necessarily reflect something of the artist’s most deeply held beliefs, whatever they may be, at least at some level, however subtle or implicit. For Tolkien, faith was not merely a set of superficial opinions but something integral to his real character—and to his own self-understanding as an author.

So, it follows that if we are to understand and appreciate Tolkien’s writings to the fullest degree, we need to come to an understanding of what he himself identified as central to his identity: his faith, which could not be disentangled from his art.

As we do this, we should keep in mind that the word “faith” can be understood in several ways, all of which are relevant to our project. As “the faith” it can refer to the doctrines and teachings handed down by the Apostles to the present day, which Catholics believe to be comprehensively conveyed and authoritatively interpreted by the Church that Jesus established. In order to understand Tolkien’s spirituality, we need to know what the content of that faith was, especially in areas that were important to him as an individual or distinct from the wider cultural and religious context in which he lived. “Faith” can also refer to personal trust in Jesus Christ and to the action of the will in assenting to, and attempting to follow, the teachings of Christ and his Church; in this sense, we can speak of “Tolkien’s faith” as his personal engagement with “the faith” as he understood it. And as a Christian, Tolkien would also have considered “faith” to be a gift from God, part of the “immeasurable riches of his grace in kindness toward us in Christ Jesus. For by grace you have been saved through faith; and this is not your own doing, it is the gift of God” (Ephesians 2:7–8). Being aware of the multilayered texture of “faith” will help us appreciate the nuances of Tolkien’s Christianity.

A Twentieth-Century English Catholic

How, then, are we to go about understanding his faith in all its complexities? First, we must do so by making full use of chronology. Tolkien’s religious life was not static; he would himself have seen it as a constant process of growth and maturation, developing from infancy “to mature manhood, to the measure of the stature of the fulness of Christ; so that we may no longer be children,” in the words of the Apostle Paul (Ephesians 4:13–14). The faith that he expressed as a mature man had its beginnings in his childhood, but was challenged, formed, and deepened throughout his life—which is why a narrative treatment is appropriate.

Second, we must pay close attention to his personal context. He was a Christian in an increasingly secular world. More specifically, he was a Catholic in a society that was still, at least residually, Anglican. He lived in a period when significant changes occurred in the way the Catholic Church understood and expressed itself; most of his life came before the Second Vatican Council, but he saw the conciliar years and had views on the changes that the council brought about. Furthermore, he was a Catholic Englishman and therefore part of a faith community that had undergone persecution, marginalization, and restrictions on civil rights, some of which lasted into Tolkien’s adulthood. Lastly, his perspective was greatly shaped by the close connection he had throughout his life to the Congregation of the Oratory of St. Philip Neri.

By examining Tolkien’s experience of his faith in the time and place and circumstances in which he found himself, we will come to a better understanding of him as a man—and therefore to a deeper appreciation of his writings.

Here I will put my cards on the table. I am, myself, a Christian and a Catholic; I believe the same things that Tolkien believed, albeit from the vantage point of a twenty-first-century American woman. I have been thinking seriously and writing about Tolkien for thirty-odd years: he was of interest to me as an agnostic undergraduate; his work provided the focus of my dissertation as an atheist graduate student; and, later, as a Protestant Christian working at a secular college, I taught his writings for the better part of a decade. In those years, I knew the bare fact that he was a Christian but nothing of the depth and texture of his spirituality, what his faith meant to him, or how it influenced his life and shaped his writings.

I have had the tremendous privilege of spending a great deal of time in England over the last fifteen years and, as a Catholic, regularly worshiping in many of the same places that Tolkien did. At the church of St. Gregory and St. Augustine, Oxford, I have frequently sat in the pew that he usually occupied and have had the privilege of speaking there with his daughter, Priscilla, who attended that church herself until her death in 2022. My own faith has been significantly shaped by English Catholicism and indeed by Oratorian spirituality, which has allowed me to gain insights into Tolkien’s experiences that would otherwise have been elusive.

My book, Tolkien’s Faith, is not an attempt to express my own particular perspective. A degree of subjectivity is inescapable, of course, but I do attempt to portray Tolkien’s faith with its own colors, contours, and emphases as accurately and objectively as I can. I endeavored to serve as a guide, to help the reader see into Tolkien’s experiences as an English Catholic Christian of the twentieth century, grounded in two important locations, Birmingham and Oxford. I wish also to note my choice of subtitle: A Spiritual Biography.

It is a spiritual biography; it focuses, necessarily, on his faith. Other events come into my account only insofar as they are relevant to the consideration of his religious life. The relative lack of detail given to matters such as his teaching, his scholarship, and his linguistic work is not a reflection of their importance but simply a necessary feature of this study’s parameters.

It is also a spiritual biography: it does not include an extended treatment or analysis of his writings, not even from a spiritual point of view. As interesting and valuable as that would be, it is beyond the purview of my argument.

It is also, specifically, a spiritual biography of Tolkien. I mention his wife and children where it is necessary for an understanding of Tolkien’s life of faith, but I do not consider their own faith commitments or indeed their lives apart from their intersection with the subject of our study.

I have drawn on a wide variety of sources in my research (which interested readers can trace in the endnotes and bibliography), aiming to get as close to Tolkien as possible. The most important sources are of course his own words in his published works, private correspondence, interviews, and in the recollections of those who knew him best. I have given particular attention to what he says in his letters, which are a rich source of information about, and insight into, his spiritual life. In considering his personal correspondence, I have endeavored always to keep in mind chronology and context: when he was writing, to whom, and for what purpose.

His daughter, Priscilla, was of the opinion that Tolkien’s letters are of great interest because they offer “an authentic means of understanding” an author; indeed, “his letters are his authentic, conscious voice.” Here, we are presented with both an opportunity and a challenge as readers seeking to understand the man and his faith. As Priscilla puts it, “I wonder if fiction is more generally appreciated because it can become so easily susceptible to the reader’s own projections, fantasies and preoccupations, whereas when the writer speaks to you directly in his own voice, it is harder to ignore what he is actually saying, and this you may not like.” If we are to gain a fuller picture of Tolkien’s life, his personality, and ultimately his creative art, we must attend to what his faith meant to him: not what it means to us (whether negatively or positively), or what we wish or assume it meant to him.

In studying a figure this well-known and well-loved, we can easily be tripped up by assumptions or misunderstandings that we do not even realize we have, and for that reason, I have tried to explain anything that might not be clear. I beg the patience of those who find that I occasionally explain what seems self-evident.

As we explore his spiritual life, we must be careful to attend to his experiences in their chronological, cultural, social, and ecclesiological context as much as possible, not abstracting them out and creating an ahistorical or static account. It is easy to picture Tolkien dressed in tweed and smoking a pipe, bent over a medieval manuscript, enjoying a pint of beer at The Eagle & Child with C.S. Lewis, or even in his army uniform in the trenches of the Somme. Our mental image gallery, to be more complete, must include tableaux such as Tolkien receiving Communion, reading the Bible, kneeling in his pew at Mass, praying with rosary beads in hand while on air-raid duty, or standing in line for the confessional. That these images may be less familiar to us does not mean they were less important for him: and so, Tolkien's Faith is an attempt to treat Tolkien’s faith on its own terms, neither critiquing it nor recommending it.

He was not a saint, if by that we mean an idealized figure who led a supposedly perfect life. As Priscilla remarked, “I don’t think you get that picture of my father even from the published letters. You certainly don’t if you read a great many of the letters!” A plaster saint? No. A cardboard Christian? No. A complex, fascinating, flawed, devout, funny, and brilliant man—yes, I think so. Read and decide for yourself what to make of his life and work when they are seen within the all-encompassing context of his faith.

EDITORIAL NOTE: This essay is excerpted from Tolkien's Faith: A Spiritual Biography (3–12) with the kind permission of Word on Fire Academic, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.