The imagery of friendship is present in the first half of John’s narrative, but it comes into sharpest focus in the second half of the Gospel, particularly during the Last Supper, when Jesus refers to his disciples as “friends” in John 15:15: "No longer do I call you slaves, for the slave does not know what his master is doing; but I have called you friends, for all things that I have heard from My Father I have made known to you.”

The reference to friendship that precedes John 15:15 prepares the way for this astounding transformation of relationship with Jesus. Specifically, this reference appears in three pericopes concerning the characters of John the Baptist, Jesus’s friends from Bethany, and the Beloved Disciple. In these three different and distinct relationships, the author of the 4th Gospel makes use of the conceptual field of friendship, relationships which, in some ways, mirror that between Jesus and the Father.

John the Baptist, the “Friend of the Bridegroom”

The noun φίλος (friend/beloved) appears for the first time in John 3:29 when John the Baptist identifies himself as “the friend of the bridegroom,” παρανύμφιος. His role is secondary in that the bridegroom is the central figure; yet, there is an intimacy between the groom and his “best man,” who had the role of preparing and presenting the bride to the bridegroom. In his book, Imaginative Love in John, Sjef van Tilborg suggests that, in a way, the reference to “the friend of the groom” in John 3:29 is more akin to the Hellenistic and Roman understanding of the friendship between groom and groomsman; in the classical world custom, there is only one παρανύμφιος, in contradiction to the Jewish customs where there are always two “best men”: one for the bride (sjosjbin) and one for the groom.[i] To be a παρανύμφιος is an honor which expresses the bond of friendship between the groom and his best friend, who is chosen as the “one and only” from among the friends.

Moreover, while a special and mutual relationship existed between Jesus and John the Baptist, as written in the Fourth Gospel, the focus is more on the contrasts between them. Throughout John 3:27-36, the superiority of Jesus is repeatedly emphasized: Jesus’s divine origin; Jesus’s permanent endowment with the Spirit; and Jesus’s distinctive role as judge. Jesus’s status must increase (v. 30), since he is the one who has come from above (v. 31) and is above all (v. 31), whereas John is merely one from the earth (v. 31). Jesus bears first-hand knowledge from above (v. 32), is sent from God, possesses the fullness of God’s Spirit (v. 34), and is thus perfectly able to speak the words of God (v. 34). Moreover, God has given Jesus authority over everything (v. 35), including the right to convey eternal life (vv. 35-36).

Nevertheless, John the Baptist, as the friend of the bridegroom, who stands and hears him, “rejoices greatly at the bridegroom’s voice” (v. 29). This is in conformity to another dimension of the friendship with John the Baptist, in that joy or sorrow was in large part dependent on the joy or sorrow of his friend. This idea is typical for the pre-Christian world of classical Greece and Rome friendship, where ideal friends shared in all of life’s experiences, whether good or bad. In this way, John the Baptist can be understood as the precursor and bridge between pagan friendship, built on natural virtue and affinity, and the Christian understanding of friendship, built on grace.

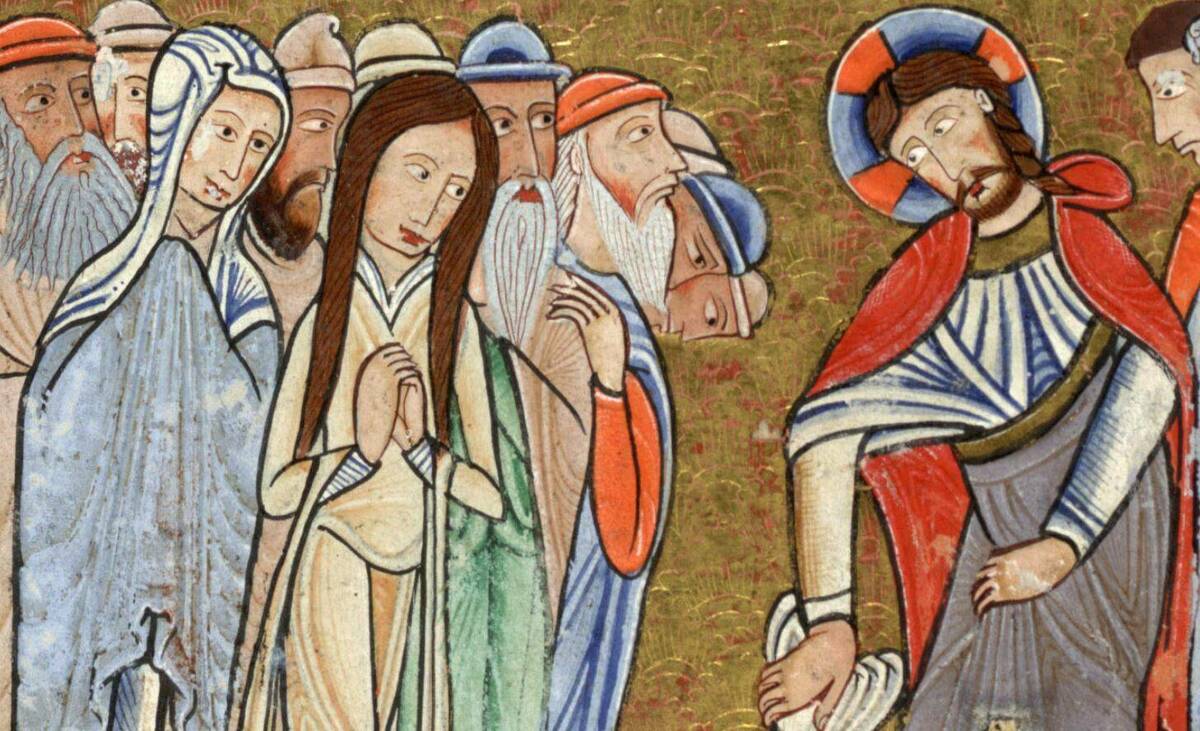

The Bethany Family as Jesus’s Friends (John 11:1-46; 12:1-8)

The Baptist is not the only Johannine character described as Jesus’s friend. Lazarus is also given this title in John 11:11: “This He said, and after that He said to them, ‘Our friend Lazarus has fallen asleep; but I go, so that I may awaken him out of sleep.’” Lazarus is the only individual character in the Fourth Gospel explicitly identified by name as Jesus’s friend.

Jesus’s love for Lazarus needs to be considered within the context of Jesus’s relationship with the sisters of Lazarus, Mary and Martha, as well. Using an imperfect tense of the verb to love (v. 5), the Gospel writer suggests the extended and continued nature of Jesus’ love; he loves Martha and Mary as well as Lazarus (v. 5), who has the added reference as being Jesus’s friend. In this pericope, Jesus is not depicted as a blood relative, but as a friend of the family; the nature of this friendship, however, is one that has made him effectively like one of the family. The friendship can be seen through the familial relationship that exists between Jesus and his love of the three siblings of Bethany. The relationships are treated with great finesse by the Johannine writer. It is remarkable that in the verbs used throughout this account, love itself and the action of loving always originates and comes from Jesus himself. This can be seen even within their summoning message (John 11:3) to Jesus stating that their brother is ill. When Mary and Martha appeal to Jesus for help based on his affection for their brother: “So the sisters sent word to Jesus, ‘Lord, the one you love is sick.’”

Jesus’s love for Lazarus seems to be a source of tension in the narrative: love as absent and love as present. On the one hand, Jesus is ready to risk his life for his friend, on the other hand, he deliberately stays away for two more days before taking any action (v. 6). This seems to suggest that, although Lazarus may well be Jesus’s friend, Jesus is the one who works entirely by the Father’s will. Jesus’s expectation that his disciples will accompany him to the Bethany family is based on the fact of Lazarus being their friend as well as his. Jesus’s reference to Lazarus as “our friend” highlights the disciples’ responsibility as friends and serves to motivate them to accompany him. Some theologians interpret Jesus’s sharing the information with his disciples that Lazarus has fallen asleep (v. 11) as an expression of friendship between Jesus and his disciples as well.

In John 11:14, the narrator describes the speech by which Jesus corrects the disciples’ misunderstanding about the truth of Lazarus’s situation as speaking παρρησία (“then Jesus told them plainly”). One of the primary distinguishing marks of a true friend in Greco-Roman culture was the use of “frank speech” (παρρησία). Unlike elsewhere in the Fourth Gospel (i.e., John 4), where the writer uses misunderstanding, irony, and metaphor as intentional literary strategies to move characters to deepening levels of theological understanding, the misunderstanding in this instance is explicitly corrected as soon as Jesus realizes it has occurred. Thus, it can be noted, that Jesus is affirming the disciples in his friendship by speaking παρρησία, frankly and plainly, to them.

After the initial misunderstanding on the part of the disciples regarding Lazarus’s death, they give voice through Thomas to their willingness to die for a friend: “Let us also go, that we may die with him” (v. 16). This declaration could also be taken as an illustration of the classical distinction between the true and the false friend, which will arise again at the Last Supper; the false friend will not be around in a time of crisis, but the true friend will be. Ironically, Thomas’s response to Jesus’s exhortation may be understood in terms of friendship: he is willing to act in accord with the responsibilities of friendship; his response may be read as his willingness to play the part of a genuine friend.

Furthermore, the notion of laying down one’s life for one’s friends is resonant with one of the classical motifs of friendship. Indeed, by going to Bethany in concern and friendship towards Lazarus, Jesus set in motion the actions that led to Jesus’s own death. The illness and subsequent death of Lazarus was the means through which the “glory of God” (v. 4) would be manifested. Hence, it may be suggested that the death, indeed the glorification of Jesus on the Cross, is ultimately reached “through the sickness of his friend.”

Jesus’s prayer before raising Lazarus makes use of the conventions of classical friendship: unity, mutuality, and equality. Yet, it is in Jesus’s friendship with God that the prayer draws its profound revelation of true friendship, perfect love, between Jesus and God the Father. Addressing God aloud, Jesus affirms that the Father “always listens” (v.42) to the Son and that the Father loves the Son. In the awesome proclamation that “The Father and I are one” (John 10:30) the full mutual and reciprocal nature of the divine friendship is revealed. When Jesus manifests divine power and calls Lazarus back, it is as if he is addressing a still-living person, and this might be read as an expression of their friendship. For his part, Lazarus may be seen as responding in a personal way to his friendship with Jesus, for he is walking back into a crisis and his taking on a lot of trouble by returning from beyond death.

The account also makes clear reference to a relationship of friends in that Jesus’s love was not restricted to Lazarus alone but equally towards his sisters, Martha and Mary, as well. The bold address and content of the message sent by them to Jesus (v. 3) is based on the friendship already present between Jesus and Lazarus. Jesus’ intervention in response to Martha’s request (vv. 21-26) also demonstrates his friendship with her. Traditionally, in the Synoptic Gospels, Martha is understood as type for the active life, and Mary is considered as the contemplative. Gradually, however, in the Johannine version, Jesus leads Martha to a full Christological confession, thus exemplifying the ideal of faith, which is the ultimate message of the Fourth Gospel itself. Indeed, it is in St. John that the closest parallel to Peter’s famous confession of Faith is to be found on the lips of Martha: “Yes, Lord, I believe that you are the Messiah, the Son of God, the one coming into the world” (John 11:27).

Likewise, in the next passage, Jesus’s friendship with Lazarus’s sister, Mary, is evident in his calling for her to come; he also calls her by name. Acting as a sheep which comes at the voice of the Good Shepherd, Mary goes outside her house to where Jesus was standing. Her immediate actions demonstrate clearly her attachment to him; hers is both a response of faith and at the same time one of deep disappointment. It is this disappointment which gives way to Jesus’s weeping over Lazarus’ death.

The use of the Greek verb δακρύω (v. 35) might portray Jesus as crying serenely while showing the genuine tears of an ordinary man at the death of his friend. In the narrative, this is the conclusion of a group of Judeans who interpreted Jesus’s crying as an expression of the depth of Jesus’s love towards Lazarus. Yet, Jesus’s sentiments at a human level for his friend must also be seen in its immediate context. In John 11:33 Jesus sees Mary weeping along with those who had come with her, and “he was deeply moved in his spirit and greatly troubled.” In John 11:38, the emotional emphasis is again repeated: “Then Jesus, deeply moved again, came to the tomb . . .” In v. 33 Jesus’s strong emotional response to the situation is described with the verbs ταράσσω (troubled) and ἐμβριμάομαι (greatly moved). The verb ταράσσω occurs six times in the Fourth Gospel, but the rare verb ἐμβριμάομαι is nearly unique; it denotes an anger-like feeling or action stirred up by a feeling of anger. Was this feeling of anger provoked by the tears of the mourners, because their tears indicated a lack of faith on their part? Or was it anger against the very powers of death? Or, possibly, is it directed even against the final rejection of Jesus himself?

Soon after the raising of Lazarus, in John 12:1-8, we find Martha “serving” during the dinner given for Jesus at the house of Lazarus. The imperfect form of the verb (διηκόνει) suggests a habitual action from the part of Martha, thus showing the familiar relationship and the friendship that exist between Jesus and Martha. The same could be said in the ensuing scene where Mary’s returned love towards Jesus is seen in the act of her anointing. Jesus allows Mary to anoint his feet, and in this is revealed that aspect of friendship that not only gives, but also receives. “Sharing” is a characteristic of friendship; a genuine friend not only “gives,” but also “receives.” Otherwise, it would seem to be a relation between benefactor, who gives or dispenses his goods, and beneficed, who receives the so-called good. The element of friendship in anointing of his feet can be seen if we take into consideration the already-existing friendship between Jesus and the family at Bethany. Indeed, the interaction between the characters in the narrative of the raising of Lazarus and what follows—the meal with Lazarus, Martha’s serving without complaint, and the anointing of Jesus’s feet by Mary—can best be understood within the framework and against the background of genuine friendship.

[i] See: Sjef Van Tilborg, Imaginative Love in John (Leiden: Brill Academic, 1993)