The religious landscape throughout history has been a forum for both conventional and innovative ideas about faith and spirituality. Many theological battles have been waged in the effort to define truth, orthodoxy, and dogma. As Farley writes, “Now, as in Schleiermacher’s time, the religious landscape is divided deeply between conservative ‘orthodoxy’ and those who despise religion itself.”[1] In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Germany found itself in the middle of such a predicament. Owing much to the spirit of the Age of Enlightenment, many theologians began to question the traditional view of God and Christianity, and instead offered new, divergent theories that made their religious faith more pragmatically relevant to themselves and to other like-minded believers.

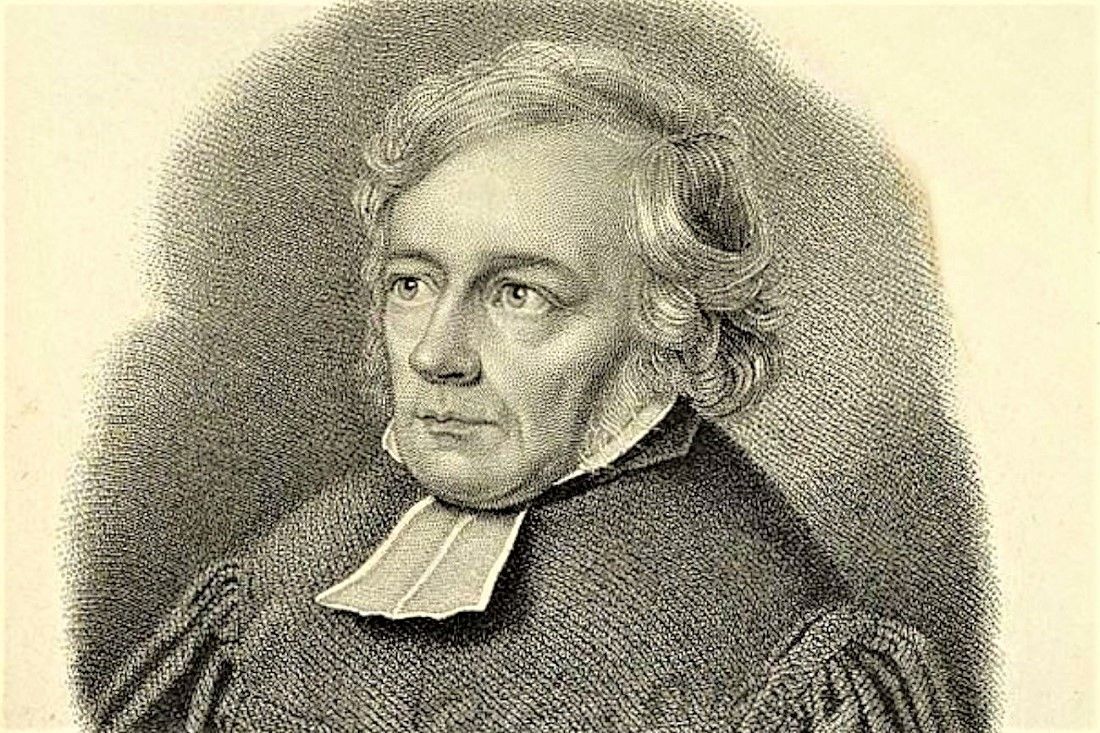

One particular German theologian, Friedrich D. E. Schleiermacher (1768–1834), proposed Enlightenment views in theology so consistently that he is usually called “The father of liberal German theology.” His innovative interpretations and theories were quite culturally influential and began a push toward a more relaxed, more creative understanding of Christianity, whose influence can still be seen in contemporary theology and culture.

It is not difficult to make connections between Schleiermacher’s philosophy and trends in postmodernity—more a zeitgeist rather than a defined school of thought—such as the following:

- Questioning any access to absolute truth,

- Questioning the trustworthiness of traditional ecclesial authority, and

- Overmphasizing the personal nature of moral and religious beliefs.

As such, it is prudent to consider the factors that most poignantly affected Schleiermacher’s theology. This, of course, will not be an exhaustive study, but will only touch upon some of the important points of Schleiermacher’s life, career, and studies.

Schleiermacher was born November 21, 1768, in Breslau (now part of Poland). His parents were devout Christians and his father was a Reformed pastor who, for all intents and purposes, was an “Enlightenment” Moravian Pietist.[2] Schleiermacher’s father, then, was open to new ideas, but still clung to his traditional heritage as an anchor. When he came of age, young Schleiermacher was sent to a Moravian school in Niesky, and there embarked upon a typical journey of studies that covered Latin and Greek classics, mathematics, botany, biblical studies, and the like. Jacqueline Mariña notes:

At Niesky (1783) Schleiermacher was exposed to an enlightened humanistic curriculum . . . There he formed a secret club in which he and his classmates read Kant, Goethe, and other contemporary German writers. As a result of this exposure, as well as of the narrow theological pedagogy of that school, he began to have doubts about certain Christian doctrines.[3]

Although this school offered much freedom to Schleiermacher for his academic development. Yet, he did not appreciate the doctrinal and praxis close-mindedness of the Moravian Brethren, which they valued over matters of intellectual advancement offered by the Enlightenment. The “pietistic religiosity and its worldview came into conflict with Enlightenment theology and above all with the humanistic cultural influence.”[4] With this blossoming conflict in his life and mind, Schleiermacher eventually left this school and began his advanced theological studies at the University of Halle.

This academic environment also did little to satisfy Schleiermacher’s desire for promoting new trends in theological thinking. His attempts at questioning the boundaries of institutional truth, a common complaint against postmodernists, were met with resistance. Yet, Schleiermacher’s suppositions were not just personal emotional tripe. As Tice states, “He [Schleiermacher] repeatedly averred that Christian faith is essentially a matter of feeling, especially ‘feeling absolutely dependent’ on God, not of adherence to thoughts or to rules for action.”[5] Thus, the “feeling” associated with Christian faith was not mere sentiment (Affekt); rather, faith was based on an internal conviction (Gefühl) sent (and received) from God, alone. In Christian Faith, Schleiermacher states, “[Faith] cannot exist in an individual until, through an impression which he has received from Christ, there is found in him a beginning—perhaps quite infinitesimal, but yet a real premonition—of the process which will put an end to the state of needing redemption.”[5]

At this point in his life, he began to fervently resist the traditionalist views of the Pietists, and started cultivating his own alternative theological views. He also began to form relationships that acted as a springboard for his new perspectives on faith. In Berlin, he encountered the German Romantic movement and became a friend of Friedrich Schlegel, a Romantic poet and leading theorist of the time. Unfortunately, because of his liberal approach to theology, Schleiermacher experienced criticism from both his superiors at the university and his father. Nevertheless, he eventually graduated and was ordained in 1794.

Schleiermacher began to think radically about his faith. First of all, “Schleiermacher rejected the necessity of Christ’s vicarious sacrifice.”[6] Then he “embarked on persistent, probing criticism in the candid recognition that old creeds may become antiquated,”[7] and he suggested that “the problem with the church’s Christological and trinitarian dogmas was not that they were religiously unfruitful, but that they made no sense.”[8] This is a recurring theme that, in essence, colors Schleiermacher’s theology for the rest of his life.

As a product of the Age of Enlightenment, Schleiermacher felt the need to understand and make relevant the theology that was so dramatically intertwined with his life. The conflicts he saw in Christianity led him to question the old dogmatic answers he had grown up with in school and Church. Such traditional ecclesiastical admonitions seemed to “labor under the defect of a limited practical usefulness”[9] and were only “productive of endless confusion.”[10]

For Schleiermacher, the old formulas of Christian institutions had failed. Rob Bell charaterizes this state of mind with contemporary post-Enlightenment zeal, “This is a misguided, toxic, and ultimately subverts the contagious stread of Jesus’ message of love, peace, forgiveness and joy that our world desperately needs to hear.”[11] So, instead of time-old dogmas of the faith, Schleiermacher offered ones that truly strengthened personal faith. He “humanized pietistic spirituality and inwardness”[12] and sought to apply them in his pastoral position. This can be clearly seen in Schleiermacher’s two most famous works, On Religion: Speeches to Its Cultured Despisers and Christian Faith.

The echoes of what Schleiermacher offered to his congregation and readers can still be heard today. His approach to Christology was “not only intellectual but also practical.”[13] The result was a liberal interpretation of Jesus and salvation. Schleiermacher was searching for a presentation of Jesus that would reach him and his contemporaries. The orthodox understanding of the nature of Jesus Christ simply made no sense to Schleiermacher. A popular Evangelical commentator points out parallels Schleiermacherian thought (in the postmodern Emerging Church movement) when he notes:

The emerging movement tends to be suspicious of systematic theology. Why? Not because we don’t read systematics, but because the diversity of theologies alarms us. No genuine consensus has been achieved, God didn’t reveal a systematic theology, but a storied narrative; and no language is capable of capturing the Absolute Truth who alone is God.[14]

Furthermore, “Schleiermacher rejected the necessity of Christ’s vicarious sacrifice”[15] because he thought that all men had an innate desire to find and seek after perfection. A true, good God would not condemn them for failing because, ultimately, they are always seeking after God regardless of finding God.

This approach led Schleiermacher logically to the conclusion that one’s salvation is not contingent upon believing the popularly–held Christian message in exact fashion. In a way like Justin Martyr, Schleiermacher believed that “fragments of divine truth could be found scattered throughout the pagan world.”[16] However, unlike Justin Martyr, he also believed that “the certainty of salvation and of faith rests on the existential experience of revelation and not on correct theological understanding and formulation.”[17]

Many theologians in his time (and in the present day) feel that in this matter, Schleiermacher treads dangerously close to pantheism. In his defense, Schleiermacher actually had noble intentions—ones modern churches still seek to incorporate into the evangelization of their communities. First and foremost, he sought to make the Christian faith real and relevant. He sought to show that faith could exist alongside science and reason. He sought to prove that mysticism did not necessarily correlate with heresy. He suggested that a loving God was in control and full of mercy and tolerance. Finally, in his writings and sermons, his central purpose was to provide an invitation for “the hearer to spiritually follow as well as to think through its [the Christian Faith’s] meaning, and by means of this living experience of participation it communicates to the hearer the feeling of an inward advance and elevation.”[18] Ironically, even in his liberalism, Schleiermacher approached Christian belief in proper Moravian spirit—focusing on inner change and integrity.

As pointed out above, Schleiermacher’s approach to theology was deep, personal, and complex. Similarly, his interpretation of scripture, too, was, by no means, only an academic interest. McLaren speaks similarly when he writes:

As I see it, religion is at its best when it leads us forward, when it guides us in our spiritual growth as individuals and in our cultureal evolution as a species. Unfortunately, religion often becomes more of a cage than a guide, holding us back rather than summoning us onward, a buffer to constructive change rather than a catalyst for it.[19]

Schleiermacher’s work, Hermeneutics, testifies to this mindset. Schleiermacher understood scripture to be a synthesis of culture and ideas. It was made of “the inner” and “the outer.” One was substance the other was form. This reality made interpretation more complicated but less rigid than the stale understandings of the Bible he disliked so much.

In order to fully understand Schleiermacher’s Christian philosophy, it is crucial to first understand his presuppositions in interpreting the Bible. Richard Corliss argues that Schleiermacher approached interpretation with the knowledge that:

1. The understanding of language requires seeing it in terms of the actions of persons. 2. These actions are to be seen in the context of communication. 3. These actions seen in the context of communication are both a manifestation of language and a manifestation of a person. 4. Understanding takes place when we can see how a linguistic act is both, at the same time, a manifestation of a language and a person.[20]

Bruce Marshall mentions that the New Testament accounts, according to Schleiermacher’s understanding, “must be read as outward expressions of an inward urge to found the kingdom of God by self-communication of a unique inward consciousness”[21] Thus, the Bible is full of language about people as well as just stories concerning those same people. The trick is to comprehend which one is the vehicle and which one is the cargo.

For Schleiermacher, the language and devices used in the Bible were carefully chosen to pass on the powerful message of redemption from God. Some ideas were presented literally; others were only metaphorical or symbolic presented. Either way, the point of both was to aid in the understanding of man’s inner relationship with God. Language, however, is multi-dimensional. It can mean different things at different times. Schleiermacher was concerned that, since the cultural meaning of language is subjective at best, it was most important to focus on discovering the original meanings of the texts. This meant possibly relegating some material to the level of cultural devices and elevating others to universal truths. In his work, The Life of Jesus, Schleiermacher put this approach to the test.

Schleiermacher sought to understand the original intent of the New Testament writers through an Enlightenment lens. His interpretation of the Gospels was an attempt to “understand what is said in the context of the language with its possibilities, and to understand it as a fact in the thinking of the speaker.” [22] He focused on the cultural language of the time and handled it, as he put it in The Life of Jesus, “as though it were the means by which the mysterious gulf between the distinct realms of outward and inward is to be crossed.” In this work, he tried to clarify the true identity of Jesus and the true purposes of Christianity. He hoped to differentiate between dogma, cultural idioms, and religious truths and thereby find a way of making Jesus relevant to his society and others to come.

Not surprisingly, Schleiermacher dangerously refuted and rejected several traditional maxims of the faith, of which he wrote,

I cannot believe that He, who called Himself the Son of Man, was the true eternal God: I cannot believe that His death was a vicarious atonement, because He never expressly said so Himself; and I cannot believe it to have been necessary, because God, who evidently did not create men for perfection, but for the pursuit of it, cannot possibly tend to punish them eternally, because they have not attained it.[23]

Such objections fly in the face of traditional, universal, orthodox Christian thought; they reject centuries of accepted doctrine, dogma, creed, and council all for a personal slant on the faith, which is echoed in his triple repetition of, “I cannot believe . . . I cannot believe . . . I cannot believe" in the passage quoted above.

Friedrich Schleiermacher died from pneumonia on February 12, 1834, with “the courage and determination of faithful acceptance and firm hope.”[24] It is no stretch to assert that he left behind a legacy of liberalism that many in the religious world consider(-ed) hermeneutically dangerous, bordering on heretical. As Nimmo writes, “The theology of Schleiermacher has regularly been treated with at best suspicion and at worst hostility on account of its purportedly inadequate doctrines of revelation in general and Scripture in particular.”[25]

Yet, it is important to keep in mind that Schleiermacher also approached his faith with the conviction that it must include deep inner reflection and a concern that the Christian faith be not only pharisaically about theology and doctrine, but also about living the truth and personal transformation.

Schleiermacher’s approach to interpretation may have been philosophically and hermeneutically perilous, but it was also genuine and ponderous. His era, as our own postmodern one, demanded a renewed examination of the Bible and his effort was a brave, risky endeavor to make that a reality. Schleiermacher’s approach still may not be embraced or lauded by all scholars and theologians (perhaps rightly so), but at the heart of his endeavor, Schleiermacher’s espoused sincere desire was to help make biblical truths real and relevant to each individual that heard or received them. As Karl Barth opined, “Schleiermacher is not dead for us and his theological work has not been transcend. If anyone still speaks today in Protestant theology as though he was still among us, it is Schleiermacher.”[26]

Yet, the original scripture writers vehemently focused on Christ Jesus as Emmanuel, “God with us” (Matt 1:22–23)—not on “Us with god.” Thus, the all-important question remains: Is Schleiermacher’s individualistic approach, with its primacy of personal surety and individual affirmation of religious matters, a benefit or a detriment to our walk with God and each other?

[1] Wendy Farley, Schleiermacher, “The Via Negativa, and the Gospel of Love,” Theology Today 65 (2008): 145.

[2] Martin Redeker, Schleiermacher: Life and Though, (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1973), 8.

[3] Jacqueline Mariña, “Introduction,” in The Cambridge Companion to Friedrich Schleiermacher (Cambridge: CUP, 2006), 2.

[4] Redeker, op. cit., 13.

[5] Friedrich Schleiermacher, Christian Faith (Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2016), 68.

[6] Redeker, op. cit., 13.

[7] B.A. Gerrish, A Prince of the Church (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1984), 36.

[8] Ibid., 39.

[9] Ibid., 38.

[10] Ibid., 40

[11] Rob Bell, Love Wins (San Francisco: HarperOne, 2011), viii.

[12] Redeker, op. cit., 41.

[13] Gerrish, op. cit., 38.

[14] Scot McKnight, “Five streams of the Emerging Church: Key Elements of the Most Controversial and Misunderstood Movement in the Church Today,” Christianity Today 51 (2008): 5.

[15] Redeker, op. cit., 13.

[16] Gerrish, op. cit., 41.

[17] Redeker, op. cit., 40.

[18] Ibid., 208.

[19] Brian McLaren, The Great Spiritual Migration (New York: Convergent, 2016), xi.

[20] Richard Corliss, “Schleiermacher’s Hermeneutic and Its Critics,” Religious studies 29 (September 1993): 364.

[21] Bruce Marshall, “Hermeneutics and Dogmatics in Schleiermacher,” The Journal of Religion 67 (January 1987): 28.

[22] Hans Kimmerle, “Introduction” to Hermeneutics: The Handwritten Manuscripts (Missuola: Scholars Press, 1977), .

[23] Friedrich Schleiermacher, The Life of Friedrich Schleiermacher, As Unfolded in His Autobiography and Letters, Vol. 1 (London: Smith & Elder, 1860), 46.

[24] Redeker, op. cit., 212.

[25] Paul Nimmo, “Schleiermacher on Scripture and the Work of Jesus Christ,” Modern Theology 31(January 2015): 62.

[26] Karl Barth, The Theology of Schleiermacher (London: T & T Clark, 1982), xiii.