On an allegorical level, the pilgrimage depicted in Dante’s Divine Comedy is an exploration of the landscape of the human soul. Our choices create the various kinds of existential hell, purgatory, and paradise experienced on this mortal coil. In Dante’s vision, our experiences of misery, our moments of conversion, and the blessings of bliss take place with attention to our concrete histories—with the persons, places, memories, and events that make up our complicated lives. It is difficult to remain a mere tourist-reader with Dante; we are enticed to become pilgrims and expose our tragic-comic lives to his “believable vision.”[1] As he guides us through his vision, Dante helps us think about liturgical participation, not as one option among many, but as a privileged site for the ordering of our loves—as the source and summit of our Christian lives.

Dante masterfully illustrates that one of the central challenges of our lives is the arduous integration of eros and agape, of desire and self-giving love. While the power of eros promises self-transcendence through intoxicating intimations of infinity, a relentless pursuit of its promises can also lead to spiritual chaos.[2] The healing and restoration of eros to its “true grandeur,” notes Pope Benedict, requires ongoing “purification and growth in maturity.” I presuppose that the ascending love of eros and the descending love of agape ought not be severed. Holding these two loves in opposition (in the manner of Anders Nygren, for example) tends to detach these realities from the complex fabric of human life. The challenge of the concrete human life is to integrate eros and agape in the one reality of love. Even if eros is manifested, at times, in a covetous manner, our commitment to authentic self-development can elevate and integrate erotic desire into care for the good of the other. Without agape, erotic love becomes impoverished and loses its own self-transcending nature. A strictly oppositional account of these two loves ignores a fundamental truth of being human: we cannot live by oblative love alone; we cannot always actively give. We desire to be desired. We receive love as a gift.

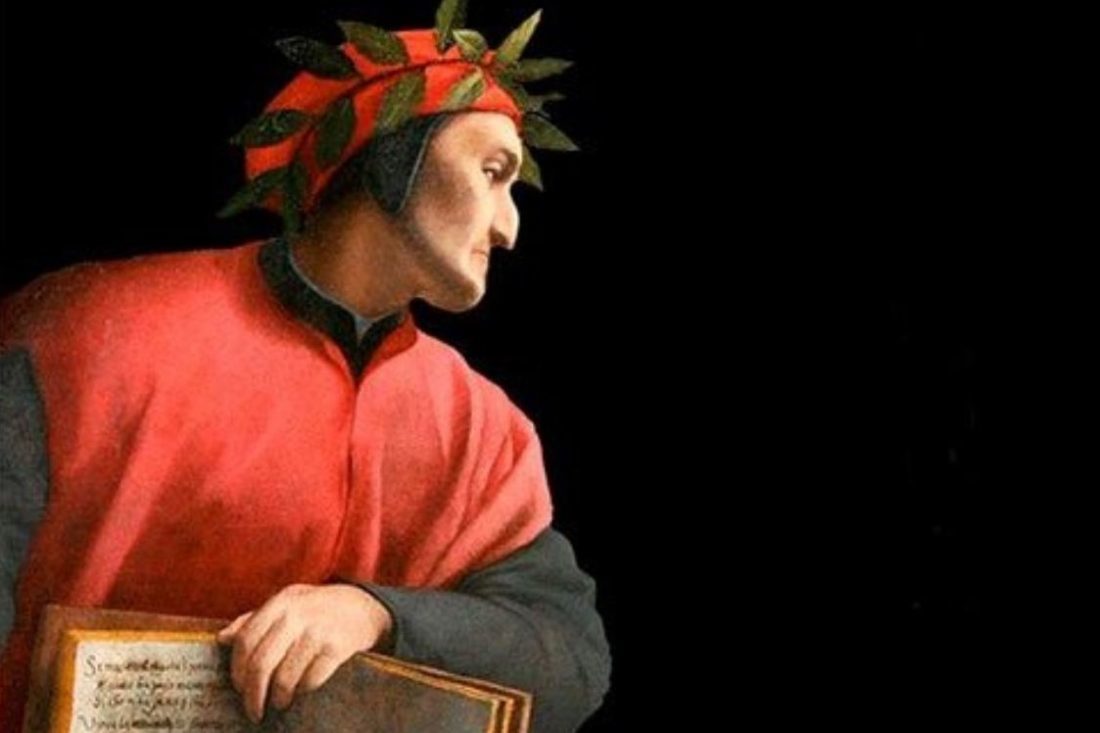

Dante as Liturgical Poet of Desire

The liturgy, as a means of human sanctification, illuminates the proper ordering of loves: that God loved us first and offers a corresponding and ongoing invitation to the respond with love. Ongoing liturgical participation engages the whole person and offers sacramental manifestations of God's love—encounters capable of awakening within us dispositions of joy “born of the experience of being loved.” As a way of exploring the liturgy as a privilege site for the formation of human desire, I turn to the “poet of desire” and his classic work, The Divine Comedy.[3] Decades ago David Tracy challenged theologians to rediscover the classics for the theological enterprise. Classics are those texts, events, images, persons, rituals, and symbols that disclose permanent possibilities of meaning and truth. Classics prioritize the “event-character” of truth and thus bear the power of putting our lives, our loves, and our commitments into question.[4] And Dante’s account of Beatrice, along with the unity of eros and agape (treated below), provides an original contribution to the history of theology with its emphasis on personal love.[5] As Hans Urs von Balthasar has noted, the earthly love of the Vita Nuova is expanded into the eschatological realm. Eros is commended as the dynamic force animating the whole journey. The love, which began on earth between two human beings, is not denied or bypassed in this depiction of the journey to God. “[I]t is carried right up to the throne of God,” Balthasar writes, “however transformed and purified. This is utterly unprecedented in the history of Christian theology.”[6]

For unfamiliar or casual readers of the Divine Comedy, it is crucial to note that liturgical references permeate the poem, especially the Purgatorio. We might even say, with Matthew Treherne, that Dante offers us an account of “liturgical personhood.”[7] In the poem, liturgical performances are not empty rituals. They instead offer a mode of language that establishes “complex relationships between the subject engaged in liturgical performance, the God to whom liturgy is offered, and the words of the liturgy itself.”[8] These liturgical performances are not quaint additions, planted to add color to an already aesthetically pleasing poem. They serve as constitutive parts of the very sacramental process that restores creatures to God.[9] Throughout the pilgrim’s ascent in the poem, the liturgical performance progressively shifts from penitence to praise, from purgatory to paradise.

The Counter-Liturgy of Paolo and Francesca

Before a tour of the liturgy’s place in Dante’s Purgatory (which is the more fitting place for liturgical presence; there is no eschatological hope among the damned), I turn first to an example from the Inferno that involves, not a liturgy as such, but the “counter-liturgy” of the two famous adulterous lovers, Paolo and Francesca. As the story goes, Francesca and her brother-in-law Paolo were innocently reading the story of Lancelot together. And then they reached the love scene between the knight and Queen Guinevere:

Time and again our eyes were brought together / by the book we read; our faces flushed and paled. / To the moment of one line alone we yielded: / it was when we read about those longed-for lips / now being kissed by such a famous lover, / that this one (who shall never leave my side) / then kissed my mouth, and trembled as he did. / Our Galehot was that book and he who wrote it. / That day we read no further (130-138).[10]

These two adulterous lovers enjoyed much popularity in the 19th century Romantic period.[11] They were heralded because of their protest of human and divine laws in favor of passionate devotion to one another. As Rene Girard voices, “What does Hell matter to them, since they are there together?”[12] Dante presents them as restless lovers never leaving one another’s side. But the Romantic interpretation contradicts the spirit of the Divine Comedy. The story in fact illuminates the power of, what Girard calls, mimetic or imitative desire. Here the written word, namely, Galleot’s account of the passion of Lancelot and Guinevere, impels “the two young lovers to act as if determined by fate; it is a mirror in which they gaze, discovering in themselves the semblances of their brilliant models.”[13] The desires of the two young lovers were mediated and formed by their own liturgical performance of the lustful lovers’ script in Galehot’s text. Thus, multiple dupes abound: Paolo and Francesca were duped by Lancelot and the queen, who were themselves duped by Gallehot; and, of course we “romantic” readers are duped by Paolo and Francesca. And rarely are we (nor were they) fully aware of such deception.[14] However, the Francesca speaking in Dante’s poem is, in reality (pace the Romantic reading), no longer a dupe. Wrapped in a web of imitation, she knows now with clarity that her perceived triumph of passion was really a defeat.[15] Dante depicts the restlessness of lust with the metaphor of starlings in the winter forever flapping their wings without any hope for rest. Francesca now spends eternity with a needy lover by her side!

In this quasi-liturgical reenactment of disordered loves, Dante offers a clear allusion to the conversion account of St. Augustine in the Confessions. Francesca’s reference (“That day we read no further”) invokes the anguished Augustine, who, in lament and the grip of sinfulness, was drawn to the text of St. Paul in book 8 of the Confessions. While Dante’s tale speaks of the performing of a text marked by distorted love, Augustine depicts a salvific transformation of love rightly ordered: “I neither wished nor needed to read further. At once, with the last words of this sentence, it was as if a light of relief from all anxiety flooded into my heart. All the shadows of doubt were dispelled.”[16]

Purgatorio: School for Sinners and Schola for Choristers

If the Inferno narrates the destiny of those hardened by disordered loves, the Purgatorio tells a story of hope; it is a story of the arduous process of repentance and ultimately shows purified eros meeting the gratuity of agape. Pride, envy, wrath, and lust, after all, are envisioned in the Purgatorio as misdirected loves: sloth as deficient love and greed, gluttony, and lust as excessive loves. A point with particular bearing on this essays is that the transformation of disordered loves in Purgatory occurs within a communal, liturgical context. As A. N. Williams notes, “Purgatory is not only a school for sinners, but a schola for choristers.”[17] The songs chanted in Purgatory are the songs of the Church’s liturgical life—the Te Deum, the Gloria, the Agnus Dei, the Te Lucis Ante Terminum, along with many psalms. The “communal chanting” signifies “that holiness is being worked here, the barriers created by self-love being worn down by the sound of many voices in concert.” In what follows, I treat several cantos in the Purgatorio that depict the liturgical transformation of love.

As a preface to his exploration of the seven capital sins, Dante depicts the pilgrim with seven P’s traced on his forehead, representing the stains of the seven capital sins that must be purged before entering into paradise. The angel holds two keys given by St. Peter: one gold, symbolizing God’s forgiveness, and the other silver, symbolizing the church’s sacramental ministry. And the pilgrim is required to take three steps, which have strong resonance to the liturgical sacrament of penance. The three steps represent the stages of repentance: self-examination (white and mirror-like), contrition (black and rough), and penance (red). As the pilgrim processes through the sacred gate, he is warned not to look back and is accompanied by the liturgical chanting of Te Deum Laudamus, a hymn of gratitude and praise.

The connection between liturgy and the transformation of love is evident, for example, in Dante’s treatment of pride. The educational punishment for the prideful in Purgatory involves the use of a stone to curb the movement of their haughty necks, forcing them to keep their faces bent to the ground (XI, 52-54). Dante emphasizes those who only desired to “excel” and who sought “poetic glory” and “earthly fame.” But, earthly fame is but a “gust of wind” that “blows about” (XI, 100-102). In this context, Dante offers two contrasting sets of sacred artistic carvings: portraits of the humble and portraits of the proud. In terms of humility, the pilgrim encounters, for example, the image of Mary accompanied with the words, “Behold the handmaid of God” (X, 43-45). The stone carvings of the proud are found on the church floor, only to be observed by heads bent low in humility. The pilgrim sees, for instance, the giant who built the Tower of Babel, stunned while observing others who shared “his bold fantasy” (XII, 34-36). In addition to sacred images, liturgical prayers and sacred music accompany those working to overcome pride. The proud recite an expanded version of the great prayer of humility: the Our Father (XI, 1-21). And the pilgrim processes to the choir singing, “Blessed are the poor in spirit,” which sounded “more sweetly than could ever be described” (XII, 109-11). Unlike the sounds of violent lament that accompanied his entrance into hell, consoling intonations permeate the passageway to purgatory (XII, 113-114). As is clear from this treatment, liturgical practices—sacred images, sacred music, prayers of the liturgy, and the chanting of psalms—were a constitutive part of the transformation of the pilgrim’s disordered love of pride.

The Liturgical Transformation of Eros

In the Purgatorio, Dante balances in a masterful way, on the one hand, a commitment to human freedom and our innate love for the good, and, on the other, a recognition of the our fallen humanity (see Cantos XVII-XVIII). Virgil’s discourse on the nature of love in purgatory offers a masterful summary of the wisdom of classical humanism as expressed in achievements of Plato and Aristotle.[18] With our emphasis on the liturgy, it is fitting to point out that this discourse is prefaced by the chanting of the beatitude, “Blessed are the peacemakers” (XVII, 68-69). Virgil begins his discourse on love by distinguishing between natural loves and rational loves. Natural love refers to the intrinsic movement of all beings in the universe to their proper ends. Sin arises only in the specifically human, rational context of love. With an echo of Augustine and Aquinas’s identification of love with rest, Dante states that all of us crave a good to put our hearts to rest. The difficulty is that we often attempt to achieve our deepest rest in deficient, misdirected, or excessive loves.

Still, Dante grants primacy to the erotic spirit in his account of the human situation. The human soul created to love moves toward “anything that pleases it.” Just as a fire’s flames always rise up, the captivated soul “begins its quest, / the spiritual movement of its love, / not resting till the thing loved is enjoyed” (19-33). For Dante, eros is naturally good; it serves as both the point of departure and the fuel toward something greater. Both the affirmation of the philosophical wisdom of eros and its limitations is captured by Virgil’s admission of the limits of the human quest. He can explain as much as reason can grasp, but admits that the rest is the work of faith (46-48).

Toward the end of Purgatory, eros becomes more and more purified, and is on the brink of encountering the gratuity of agape reflected in the person of Beatrice. Beatrice, of course, refers to the real Florentine girl who Dante met at the age of nine. In the Vita Nuova, Dante describes love at first sight and considered her the object of his passion and even the embodiment of God’s love (Collins, 5). Beatrice emerges on the scene within a liturgical setting; she is chanting, “Blessed are the pure of heart, for they shall see God.” The very name of Beatrice melts the pilgrim’s stubbornness away, and is accompanied by the consoling words of Christ: “Come, you who are blessed by my Father. Inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world.” This chant radiated so much light that the pilgrim was compelled to turn his eyes away (59-60). The guidance of Virgil has reached its end; eros has shown its limits. Virgil urges the pilgrim to embrace Beatrice’s “lovely eyes rejoicing” (136-141).

In his poetic mediations on love, Dante envisions the pilgrim entering, not the “Dark Wood” of the Inferno, but the “Divine Forest” of purgatory. The “Divine Forest” symbolizes a place of human innocence and purity, rarely glimpsed in our postlapsarian state. In this place, Dante depicts a woman, whose very presence radiates joy, purity, and innocence. Rich with sweet sensuality, these cantos show a beautiful woman in love with God. The pilgrim is compelled to pray the words of Psalm 92 and to clear the mist that clouds his mind (XXVIII, 79-81). “For you, O Lord, have made me glad by your work; at the work of your hands I sing for joy.” And she chants further from Psalm 32: “Happy are those whose transgression is forgiven, whose sin is covered. Happy are those to whom the Lord imputes no iniquity, and in whose spirit there is no deceit.” Dante’s poetic account of the liturgical chanting of these psalms of praise transcends the pure poetry of the aesthetes, showing an awareness of the joy that arises when we actually experience the universe as a reflection of the Creator.

Dante depicts a liturgical pageant breaking out in this “Divine Forest.” The pilgrim experiences the burst of enduring, incandescent light and the “gentle melody” drifting “through the luminous atmosphere.” His taste of these “ineffable delights” and his experience of this “blissful trance” indicate the “first fruits of eternal joy” and his “yearning for still more happiness to come.” During this experience, he hears the joyous chanting of Hosanna. The remainder of this canto is so full of symbolism that we can only capture a glimpse of it here. Suffice it to say, Dante offers an allegorical representation of the multitude of divine gifts: the Bible, the sacraments, the theological virtues and the gifts of the Holy Spirit (XXIX). After this liturgical procession, Dante encounters Beatrice directly; she is adorned with clothes that represent the theological virtues of faith, hope, and charity. The language that the pilgrim uses to describe Beatrice is infused with beauty and mystery: his eyes were struck by “the force / of the high, piercing virtue” he had known in his youth, inspiring in him the confidence “that makes a child run to its mother’s arms, / when he is frightened or needs comforting” (XXX, 40-45). And, the pilgrim hears the choir of angels singing, “In you, O Lord, have I put my trust.”

Yet, the pilgrim was not fully purified. With the penitential posture of Purgatory, he stood before Beatrice paralyzed and confused, as he contemplated the “bitter memories” that have not yet been purged (XXXI, 11-12). The pilgrim was shattered by the intensity of his sins. With his confession of guilt imminent, Beatrice focuses on his desire: “In your journey of desire for me, / leading you toward that Good beyond which naught / exists to which a man’s heart may aspire, / what pitfalls did you find, what chains stretched out / across your path, that you felt you were forced / to abandon every hope of going on” (22-27). The pilgrim responds in tears that those roadblocks were false joys offered by the world and served as substitutes for seeing her face (34-36). He hears the liturgical chanting of Psalm 51, “Cleanse me of sin” (98). And upon his confession, the “lovely lady” opened her arms, embraced his head, and dipped it into the stream (100-102). During this baptism, the “yearning flames” of the pilgrim’s desire fixed his eyes on Beatrice’s own “brilliant eyes.” In Dante’s words, he discovered “like sunshine in a mirror” the twofold creature “in her eyes, / reflecting its two natures, separately” (121-123). In other words, when looking into the eyes of Beatrice, the pilgrim saw the reflection of Christ in his humanity and divinity—an ordering of eros and agape, par excellence.

From Wandering Eros to Doxological Love

If the use of liturgy in purgatory corresponds to the broader scheme of penance and also anticipates the proper liturgical posture in paradise, the Paradiso presents liturgy as a doxological act. More than simply “conferring a certain mood on the poem,” the heavenly liturgy in paradise stands as the apex toward which the poem has been building—a process “bound up Christologically with the notion of the restoration of the relationship between Creator and creature.”[19]

Particularly relevant to this transformation of human love is Dante’s account of those who were dominated by a carnal love ultimately transformed into the heights of agape.[20] The pilgrim encounters, just to take one example, a woman named Cunizza, who was known for her promiscuous love life. Cunizza left “her first husband for a troubadour, then travelled widely in Italy with a knight, and later remarried three times.”[21] Her well-documented affairs coined her the nickname, “child of Venus.”[22] Over time, however, Cunizza became known for her unparalleled compassion and deep social concern.[23] Whereas Francesca was doomed to be forever at the side of her adulterous lover, Cunizza displayed a peaceful demeanor as she reflects on her past sins. She humbly acknowledges that she had been overcome by the carnality of eros, by the light of Venus: “but gladly I myself forgive in me / what caused my fate, it grieves me not at all – / which might seem strange, indeed, to earthly minds” (IX, 34-36). Her humble disposition provided the soil for the kind of self-forgiveness and liberation from guilt, and hence, the kind of inner peace rarely glimpsed by those who struggle with sexual compulsion. Cunizza admits that her life had been dominated by sex, but that her “wandering eros” was refined into “responsible love.” The memory of her past is the occasion for joy; divine forgiveness has turned the pain of remorse into laughter and song.[24] In sum, Dante depicts God as an artist who fashions human loves. God implants eros into creatures and guides them into the beauty of self-giving love. Those dominated by excessive carnal love can ultimately experience, by the gratuity of grace, divine healing. “In Dante’s universe,” as James Collins notes, “human eros is an asset: it freely, humbly, and innocently admits the basic need to be loved and to love. Eros’s sensitivity opens the human soul to receive the divine guest knocking at the door. The self-righteous remain closed and hardened by their own justice and pride.”[25]

Foretaste of Eschatological Love

Vatican II’s Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy describes the eschatological dimension of the Church’s liturgy: “In the earthly liturgy we take part in a foretaste of that heavenly liturgy which is celebrated in the holy city of Jerusalem toward which we journey as pilgrims.” In the Paradiso, Dante depicts the pilgrim contemplating the Trinitarian Love made present in the liturgy. He was so enraptured by divine love that even Beatrice left his mind (X, 58-60). And since there is no place for envy in heaven, the pilgrim’s orientation of his love to God did not displease Beatrice; rather, she smiled, and radiated the splendor of “laughing eyes” (X, 61-63). The poet highlights a diversity of saints and theological voices that modeled the eros of the human spirit—voices who nurtured in significant ways the kind of unrestricted desire to understand the universe that led many to wonder and to pray throughout the centuries: Thomas Aquinas, Albert the Great, Gratian, Peter Lombard, Pseudo-Dionysius, Augustine, and Boethius, Venerable Bede, Richard of St. Victor, among others. Dante envelops these diverse (and sometimes opposing theologians) in erotic-liturgical imagery (X).

Them, as the tower-clock calls us to come / at the hour when God’s bride is roused from bed / to woo with matin song her Bridegroom’s love, / with one part pulling thrusting in the other, / chiming, ting-ting, music so sweet the soul, / ready for love, swells with anticipation; / so I was witness to that glorious wheel / moving and playing voice on voice in concord / with sweetness, harmony unknown, save there / where joy becomes one with eternity. (X, 139-148)

This suggestive image of the Church as the bride of God, Paolo Nasti suggests, “rests upon the adoption of several words and images drawn from the Song of Songs.”[26] Dante intended “to make use of all the different meanings that biblical exegetes attributed to the Bride of the Song of Songs”:

The Bride of God of the Song of Songs was interpreted allegorically as the Church Militant, tropologically as the soul, and analogically as the community of the blessed. At a first level of interpretation (allegorical), therefore, the Bride evoked by the poet can be read in full accordance with the exegetical tradition as the Church Militant, here seen as a congregation galvanized by their love for the Creator in the hours of the morning liturgy. From a tropological/moral perspective, the image is also meant to represent the soul united as a Bride to her loving God in the secrecy of daily prayer. The anagogical senses associated with the bridal metaphor are activated, indirectly, by the context of the comparison. Dante compares the love-making of the Church to the celestial bliss enjoyed by the souls united to God in their final embrace.[27]

By grounding this continuity between the earthly and heavenly liturgies in the Song of Songs, Dante places self-giving love at the heart of the both communities. It is self-giving love that bonds “Christ and his members in both realms.[28] The pilgrim church on earth is being formed in an ongoing way by the fuel of erotic-agapic desire, by a “desire to be united to God, and desire to rejoice in him and in the other blessed souls.”[29]

In the context of this discussion of the Song of Songs and the centrality of erotic-agapic love, it is quite fitting that Beatrice does not escort Dante into final union with Trinitarian love. Beatrice hands him over to St. Bernard of Clairvaux, the saint known for his Sermons on the Song of Songs, and his treatises On Contemplation and On Loving God. If Virgil symbolized the light of reason and Beatrice, the light of faith, then Bernard symbolized the higher light of glory, which brings the soul into loving union with God, the kind of union that is anticipated in earthly contemplation. St. Bernard directs him to Mary, on whom the pilgrim’s ultimate spiritual progress depends. In the final canto, Bernard prays to Mary to protect the pilgrim and to “raise his vision higher still / to penetrate the final blessedness” (XXXIII, 26-27). Bernard prays, with attention to desire, to “keep his affections sound / once he has had the vision and returns” (35-36) and to protect him “from the stirrings of the flesh” (37). Dante is ushered progressively into this vision and “so transformed within that Light / that it would be impossible to think / of ever turning one’s eyes from that sight / because the good which is the goal of will / is all collected there” (100-104). In this ineffable experience, his “words have no more strength than does a babe / wetting its tongue, still at its mother’s breast” (107-108). How do human beings, the pilgrim wonders, fit into this mysterious Trinitarian “circling” (129)? At a loss for answers, he is struck by a flash of understanding: “At this point power failed high fantasy / but, like a wheel in perfect balance turning, / I felt my will and my desire impelled / by the Love that moves the sun and the other stars” (142-145). In this liturgical-doxological event that ends the poem, the pilgrim receives a foretaste of the mysterious joy of the eschatological banquet.

Conclusion

As the poet of desire, Dante has much to say to the variety of ways we speak of faith today. 21st century theology might attend more fruitfully to the plurality of, what David Ford has called, “moods of faith.”[30] One often identifies faith with the indicative mood (“This is what is believed”) and the imperative mood (“Do this”). But, other “moods” are operative in Dante. We witness the pilgrim persistently questioning (interrogative mood) even until the final lines of the poem—a concrete embodiment of the medieval quaestio. Perhaps the whole Commedia operates in the subjunctive mood, identifying what “might be.” Yet, the most prominent of Dante’s moods” is, in fact, as Ford notes, the “optative” mood. The optative mood privileges what we wish for or long for—in sum, what we desire. And it is in the Church’s liturgy that we are called to full, active, conscious, embodied participation in love; it is the privileged, communal site for seeking the face of God.

[1] David Tracy, “Foreword” to James Collins, Pilgrim in Love (Chicago: Loyola University Press, 1984), ix. All citations in this paragraph, Foreword to Collins’ book.

[2] I am drawing in this paragraph from Pope Benedict XVI, Deus Caritas Est, (2005), #3-8. http://w2.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/encyclicals/documents/hf_ben-xvi_enc_20051225_deus-caritas-est.html

[3] See Dante’s Commedia: Theology as Poetry, ed. Vittorio Montemaggi and Matthew Treherne (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2010). This volume of collected essays is indispensable for any exploration of theological themes in Dante’s work.

[4] Tracy, The Analogical Imagination (New York: Crossroad, 1998), 167.

[5] Hans Urs Balthasar, The Glory of the Lord: A Theological Aesthetics: III: Studies in Theological Styles: Lay Styles.

[6] Ibid., 31-32.

[7] Matthew Treherne, “Liturgical Personhood: Creation, Penitence, and Praise in the Commedia” in Dante’s Commedia: Theology as Poetry, 131-60.

[8] Treherne, “Liturgical Personhood,” 131

[9] Treherne, “Liturgical Personhood,” 132.

[10] All references to the Divine Comedy are to Dante Alighieri, The Portable Dante, ed. Mark Musa (New York: Penguin, 2003).

[11] Rene Girard, “The Mimetic Desire of Paolo and Francesca,” “To double business bound”: Essays on Literature, Mimesis, and Anthropology (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1978), 1.

[12] Girard, “The Mimetic Desire of Paolo and Francesca,” 1.

[13] Girard, “The Mimetic Desire of Paolo and Francesca,” 2.

[14] Girard, “The Mimetic Desire of Paolo and Francesca,” 2.

[15] Girard, “The Mimetic Desire of Paolo and Francesca,” 3.

[16] Augustine, Confessions, trans. Henry Chadwick (Oxford: OUP, 1991), 152.

[17] A. N. Williams, “The Theology of the Comedy,” in The Cambridge Companion to Dante, ed. Rachel Jacoff (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 215.

[18] Collins, Pilgrim in Love, 146.

[19] Treherne, “Liturgical Personhood,” 150

[20] James Collins, Pilgrim in Love, 226.

[21] Collins, Pilgrim in Love, 228.

[22] Collins, Pilgrim in Love, 228.

[23] Collins, Pilgrim in Love, 228.

[24] Collins, Pilgrim in Love, 229.

[25] Collins, Pilgrim in Love, 230.

[26] Paolo Nasti, “Caritas and Ecclesiology in Dante’s Heaven of the Sun,” 226.

[27] Nasti, “Caritas and Ecclesiology in Dante’s Heaven of the Sun,” 226-227.

[28] Nasti, “Caritas and Ecclesiology in Dante’s Heaven of the Sun,” 230.

[29] Nasti, “Caritas and Ecclesiology in Dante’s Heaven of the Sun,” 231.

[30] I am drawing here from David F. Ford, “Dante as Inspiration for Twenty-First Century Theology,” in Dante’s Commedia: Theology as Poetry, 321-3.